Mary Wollstonecraft facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary Wollstonecraft

|

|

|---|---|

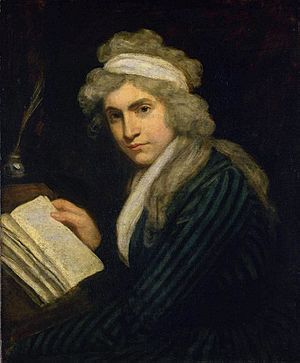

Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie, c. 1797

|

|

| Born | 27 April 1759 Spitalfields, London, England |

| Died | 10 September 1797 (aged 38) Somers Town, London, England |

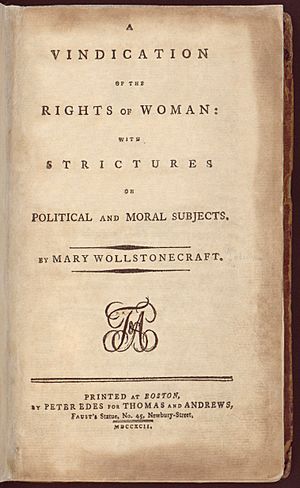

| Notable work | A Vindication of the Rights of Woman |

| Spouse | |

| Partner |

|

| Children |

|

Mary Wollstonecraft (born April 27, 1759 – died September 10, 1797) was a British writer and thinker. She is famous for supporting women's rights. Many people today see her as one of the first feminist philosophers. Both her life and her writings have greatly influenced feminists.

During her short career, she wrote novels, essays, and a travel book. She also wrote a history of the French Revolution and a children's book. Wollstonecraft is best known for her book A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). In this book, she argued that women are not naturally weaker than men. She believed they only seemed weaker because they lacked education. She thought both men and women should be seen as smart, thinking people. She imagined a society built on good reasoning.

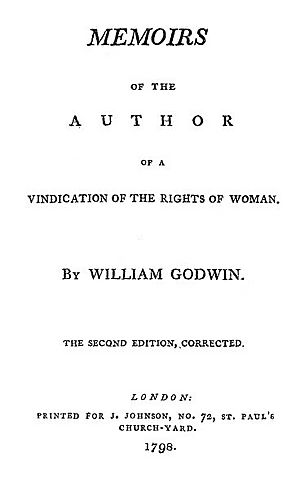

After Wollstonecraft died, her husband published a book about her life. This book shared details about her life choices. These details unfortunately harmed her reputation for nearly a century. But when the feminist movement grew in the 1900s, her ideas about equality for women became very important.

Mary Wollstonecraft married the philosopher William Godwin. He was one of the early thinkers behind the anarchist movement. She died at age 38, leaving behind some unfinished writings. She passed away just 11 days after giving birth to her second daughter, Mary Shelley. Mary Shelley later became a famous writer herself, known for Frankenstein.

Contents

Mary Wollstonecraft's Life Story

Growing Up in London

Mary Wollstonecraft was born on April 27, 1759, in Spitalfields, London. She was the second of seven children. Her family had a good income when she was young. However, her father slowly lost their money on bad projects. This meant her family often had to move. Their money problems became so bad that her father made her give him money she was supposed to inherit. He was also a violent man who would sometimes hit her mother. As a teenager, Mary would sleep outside her mother's door to protect her.

Mary also took care of her younger sisters, Everina and Eliza. In 1784, she helped Eliza leave her husband and baby. Eliza was likely suffering from postpartum depression. Mary arranged everything for Eliza to escape. This showed Mary's willingness to challenge what society expected. However, Eliza faced social disapproval and poverty because she could not remarry.

Two friendships were very important in Mary's early life. The first was with Jane Arden. They read books together and attended lectures. Mary loved the intellectual discussions at Arden's home. She valued this friendship deeply. She wrote to Arden, "I have formed romantic notions of friendship... I must have the first place or none." Her letters also showed the strong emotions she felt throughout her life.

Her second and more important friendship was with Fanny Blood. Mary met Fanny through the Clares, a couple who became like parents to her. Mary said Fanny helped her open her mind.

Becoming a Writer

Unhappy at home, Mary left in 1778. She took a job as a lady's companion for a widow in Bath. Mary found it hard to get along with the woman. She later wrote about these difficulties in her book Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787). In 1780, she returned home to care for her dying mother. After her mother's death, Mary moved in with the Blood family. She realized that she had perhaps idealized Fanny. Fanny was more interested in traditional female roles than Mary was. Still, Mary remained loyal to Fanny and her family. She often helped Fanny's brother with money.

Mary had dreamed of living with Fanny in a "female utopia." They planned to rent rooms and support each other. But this dream ended because of money problems. To earn a living, Mary, her sisters, and Fanny started a school together. It was in Newington Green, a community of English Dissenters. Fanny soon got married and moved to Lisbon, Portugal. She hoped the change would improve her health. But Fanny's health worsened when she became pregnant. In 1785, Mary left the school to nurse Fanny. Sadly, Fanny died. Mary's leaving also caused the school to fail. Fanny's death deeply affected Mary. It inspired her first novel, Mary: A Fiction (1788).

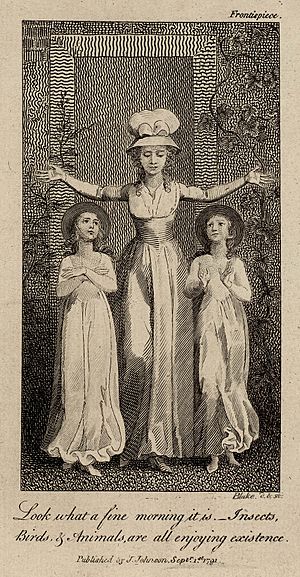

After Fanny's death in 1785, Mary's friends helped her find a job. She became a governess for the Kingsborough family in Ireland. She did not get along with Lady Kingsborough. But the children found her an inspiring teacher. One daughter later said Mary "had freed her mind from all superstitions." Some of Mary's experiences as a governess appeared in her children's book, Original Stories from Real Life (1788).

Mary was frustrated by the few job choices for respectable but poor women. She wrote about this in Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. After only a year as a governess, she decided to become a writer. This was a bold choice. Few women at that time could earn a living by writing. She wrote to her sister in 1787 that she wanted to be "the first of a new genus."

She moved to London. With help from the publisher Joseph Johnson, she found a place to live and work. She learned French and German. She translated books, including Of the Importance of Religious Opinions and Elements of Morality, for the Use of Children. She also wrote reviews for Johnson's magazine, the Analytical Review.

Mary's knowledge grew during this time. She read for her reviews and met many thinkers. She attended Johnson's famous dinners. There she met the writer Thomas Paine and the philosopher William Godwin. Johnson became more than a friend to her. She called him a father and a brother.

In London, Mary lived on Dolben Street. She became interested in the artist Henry Fuseli, who was married. She admired his "genius" and "grandeur of his soul." She suggested a platonic living arrangement with Fuseli and his wife. But Fuseli's wife was upset, and he ended the relationship.

After this, Mary decided to travel to France. She wanted to escape the embarrassment. She also wanted to be part of the revolutionary events she had praised in her book Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790). She wrote Rights of Men to respond to Edmund Burke's conservative views on the French Revolution. This book made her famous very quickly. She called the French Revolution a "glorious chance to obtain more virtue and happiness."

Mary was compared to famous thinkers like Joseph Priestley and Thomas Paine. She continued her ideas from Rights of Men in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). This became her most famous and important work. Her fame reached France. When French statesman Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord visited London in 1792, he met her. She asked him to give French girls the same right to education as French boys.

Life in Revolutionary France

Mary left for Paris in December 1792. She arrived about a month before King Louis XVI was executed. Britain and France were close to war. Many people told her not to go. France was in chaos. She found other British visitors and joined a group of foreigners in the city. In Paris, Mary mostly spent time with the moderate Girondins. She did not join the more extreme Jacobins.

On December 26, 1792, Mary saw the former king, Louis XVI, being taken to his trial. She was surprised to find tears in her eyes. She wrote that he sat "with more dignity than I expected."

France declared war on Britain in February 1793. Mary tried to leave France for Switzerland but was not allowed. In March, the Jacobin group took power. They started a strict government to prepare France for war.

Life became very hard for foreigners in France. First, they were watched by the police. To get a permit to live there, they needed six written statements from French people. These statements had to say they were loyal to the republic. Then, on April 12, 1793, all foreigners were forbidden to leave France. Even though Mary supported the revolution, her life became very difficult. The Girondins, her friends, lost power to the Jacobins. Some of Mary's French friends were executed by guillotine.

Meeting Gilbert Imlay and Motherhood

Mary had just written Rights of Woman. She wanted to test her ideas. In the exciting atmosphere of the French Revolution, she met Gilbert Imlay. He was an American adventurer. She fell deeply in love with him.

Mary was somewhat disappointed by what she saw in France. She wrote that people still acted like servants to those in power. She also felt the government was "corrupt" and "brutal." She was upset by how the Jacobins treated women. They refused to give women equal rights. They said women should only be helpers to men.

As daily arrests and executions began during the Reign of Terror, Mary came under suspicion. She was a British citizen and friends with leading Girondins. On October 31, 1793, most Girondin leaders were executed. When Imlay told Mary the news, she fainted.

Imlay was taking advantage of the British blockade of France. This blockade caused shortages and rising prices. He chartered ships to bring food and soap from America. He sold these goods at high prices to French people who still had money. Imlay's business helped him stay free during the Terror. To protect Mary from arrest, Imlay falsely told the U.S. embassy that they were married. This made her an American citizen. Some of her friends, like Thomas Paine, were arrested.

Mary called life under the Jacobins "nightmarish." There were huge parades during the day. Everyone had to cheer loudly or risk being suspected of disloyalty. At night, police raided homes to arrest "enemies of the republic."

Mary soon became pregnant with Imlay's child. On May 14, 1794, she gave birth to her first daughter, Fanny. She named her after her close friend. Mary was overjoyed. While in Le Havre, she wrote a history of the early revolution. It was called An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution. It was published in London in December 1794. Imlay, however, became unhappy with Mary. He eventually left her. He promised to return to her and Fanny in Le Havre. But his long absences convinced Mary he had found another woman.

Return to England and William Godwin

Mary returned to London in April 1795, looking for Imlay. But he rejected her. In a last effort to win him back, she went on a business trip for him. She traveled to Scandinavia to find a Norwegian captain. This captain had run off with silver that Imlay was trying to get past the British blockade. Mary took this risky trip with only her young daughter and her maid. She wrote about her travels and thoughts in letters to Imlay. Many of these were later published as Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark in 1796.

Slowly, Mary returned to her writing life. She reconnected with Joseph Johnson's group. She also met William Godwin. Godwin and Mary's relationship started slowly. But it grew into a strong love affair. Godwin had read her Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. He later wrote that it was a book that would make a man fall in love with its author. He felt she spoke of her sorrows in a way that was both sad and tender. At the same time, she showed great intelligence.

Once Mary became pregnant, they decided to marry. This was so their child would be legitimate. Their marriage revealed that Mary had never been married to Imlay. Because of this, she and Godwin lost many friends. Godwin was also criticized because he had argued against marriage in his book Political Justice. They married on March 29, 1797. Godwin and Mary moved to 29 The Polygon in Somers Town. Godwin rented a separate apartment nearby as a study. This allowed them both to keep their independence. They often wrote letters to each other. By all accounts, their relationship was happy and stable, though short.

Birth of Mary Shelley and Death

On August 30, 1797, Mary Wollstonecraft gave birth to her second daughter, Mary. Mary Wollstonecraft died on September 10. She passed away due to problems from childbirth. Godwin was heartbroken. He wrote to a friend, "I firmly believe there does not exist her equal in the world." He felt they were meant to make each other happy. He did not expect to find happiness again. She was buried in the churchyard of St Pancras Old Church. Her tombstone reads "Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: Born 27 April 1759: Died 10 September 1797."

Mary Wollstonecraft's Important Works

Ideas on Education

Most of Mary Wollstonecraft's early writings were about education. She created a collection of writings for young women called The Female Reader. She also translated two children's books. Her own books also discussed education. In Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) and Original Stories from Real Life (1788), she supported teaching children important values. These values included self-discipline, honesty, and being happy with what you have. Both books also stressed the importance of teaching children to think for themselves. This showed her debt to the philosopher John Locke.

However, Mary also emphasized religious faith and feelings. This made her work different from Locke's. It connected her to the idea of "sensibility" popular at the time. Both books also argued for educating women. This was a debated topic then. She would return to it often, especially in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Mary believed that well-educated women would be good wives and mothers. They would also help their country.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is one of the first books about feminist philosophy. In it, Mary Wollstonecraft argued that women should have an education that fits their role in society. She then redefined that role. She said women are vital to the nation because they educate children. She also believed they could be "companions" to their husbands, not just wives.

Instead of seeing women as pretty decorations or property, Mary said they are human beings. They deserve the same basic rights as men. Large parts of the book strongly criticized writers who wanted to deny women an education. For example, Jean-Jacques Rousseau famously argued that women should be educated only to please men.

Wollstonecraft stated that many women at the time were silly and shallow. She called them "spaniels" and "toys." But she argued this was not because they were born less smart. It was because men had kept them from getting an education. She wanted to show how much women were limited by their poor education. She wrote: "Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman's sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison." She meant that if young women were not taught to focus only on beauty, they could achieve much more.

While Mary called for equality in some areas, like morals, she did not explicitly say men and women are equal in every way. She did claim they are equal in the eyes of God. However, she also mentioned the idea that men's strength might be superior. Her ideas about equality have made it hard to label her a "modern feminist." This is partly because the word "feminist" did not exist until the 1890s.

One of Mary's strongest criticisms in Rights of Woman was against too much "sensibility," especially in women. She argued that women who gave in to their feelings too much were "blown about by every momentary gust of feeling." Because they were "the prey of their senses," they could not think clearly. She claimed they harmed not only themselves but society. These women, she believed, would destroy civilization, not improve it. Mary did not think reason and feeling should be separate. Instead, she believed they should work together.

Mary also laid out a specific plan for education. In her chapter "On National Education," she argued that all children should go to a "country day school." They should also get some education at home to "inspire a love of home and domestic pleasures." She also believed schools should be co-educational. She thought men and women, whose marriages are "the cement of society," should be "educated after the same model."

Mary wrote her book for the middle class. She called this the "most natural state." Her book encouraged modesty and hard work. It also criticized the uselessness of the rich. But Mary was not always a friend to the poor. For example, in her education plan, she suggested that after age nine, poor children should be separated from the rich. They would go to a different school, unless they were very brilliant.

Novels by Mary Wollstonecraft

Both of Mary Wollstonecraft's novels criticized the traditional idea of marriage. She believed it harmed women. In her first novel, Mary: A Fiction (1788), the main character, Mary, is forced into a marriage without love. She finds love and affection outside marriage through two strong friendships. One is with a woman, and one is with a man.

Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman (1798) was unfinished and published after her death. It is often seen as her most radical feminist work. It tells the story of a woman locked in a mental asylum by her husband. Like Mary, Maria finds happiness outside marriage. She has a relationship with another patient and a friendship with one of her caretakers. Neither of Mary's novels shows successful marriages. However, she did suggest such relationships were possible in Rights of Woman. At the end of Mary, the heroine believes she is going "to that world where there is neither marrying, nor giving in marriage." This suggests a positive future without traditional marriage.

Both novels also criticized the idea of "sensibility." This was a popular philosophy at the end of the 1700s. Mary itself is a novel of sensibility. Mary tried to use the style of that genre to challenge sentimentalism. She believed it was bad for women because it made them rely too much on their emotions. In The Wrongs of Woman, the main character's romantic daydreams are shown as very harmful.

Female friendships are key to both of Mary's novels. The friendship between Maria and Jemima is especially important. Jemima is the servant watching over Maria in the asylum. This friendship is based on a shared bond of motherhood. It is between a wealthy woman and a poorer woman. This is one of the first times in feminist writing that suggests women of different economic backgrounds can have the same interests because they are women.

Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796)

Mary Wollstonecraft's Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark is a very personal travel story. The 25 letters cover many topics. These include thoughts on Scandinavia and its people. They also include philosophical questions about identity. She also wrote about her relationship with Gilbert Imlay, though she did not name him.

Using the idea of the "sublime," Mary explored the connection between herself and society. The "sublime" refers to something so grand or powerful it inspires awe and fear. Her letters show the strong influence of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. They share themes from his book Reveries of a Solitary Walker (1782). These themes include searching for happiness, rejecting material things, and loving nature. They also show the important role of feelings in understanding. While Rousseau eventually turned away from society, Mary celebrated home life and progress in her book.

Mary promoted personal experience, especially with nature. She explored how the sublime connects with feelings. Many letters describe the amazing scenery of Scandinavia. She wrote about her desire to feel a deep connection to nature. In doing so, she valued imagination more than in her earlier works. As in her previous writings, she supported freedom and education for women. However, in a change from her earlier works, she showed the harmful effects of trade on society. She contrasted a thoughtful connection to the world with a focus on money. She linked this money-focused attitude to Imlay.

Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark was Mary Wollstonecraft's most popular book in the 1790s. It sold well and received good reviews. William Godwin wrote that it was a book that would make a man fall in love with its author. It influenced Romantic poets like William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. They used its themes and style in their own works.

Images for kids

-

Green plaque on Newington Green Primary School, near the site of a school that Wollstonecraft, her sisters (Everina and Eliza), and Fanny Blood set up; the plaque was unveiled in 2011.

-

Blue plaque at 45 Dolben Street, Southwark, where she lived from 1788; unveiled in 2004 by Claire Tomalin

-

Plaque on Oakshott Court, near the site of her final home, The Polygon, Somers Town, London

See also

In Spanish: Mary Wollstonecraft para niños

In Spanish: Mary Wollstonecraft para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |