Mary Shelley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary Shelley

|

|

|---|---|

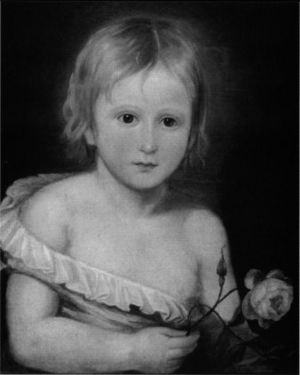

Richard Rothwell's portrait of Shelley was shown at the Royal Academy in 1840, accompanied by lines from Percy Shelley's poem The Revolt of Islam calling her a "child of love and light".

|

|

| Born | Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin 30 August 1797 London, England |

| Died | 1 February 1851 (aged 53) London, England |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Notable works | Frankenstein (1818), see more... |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4, including Percy Florence |

| Parents | |

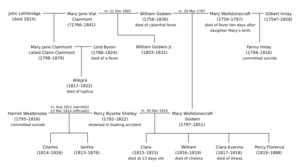

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (born Godwin; August 30, 1797 – February 1, 1851) was an English writer. She is famous for her Gothic novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818). This book is seen as an early example of science fiction.

Mary also helped publish and promote the works of her husband, the Romantic poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley. Her father was the political philosopher William Godwin. Her mother was the philosopher and advocate for women's rights, Mary Wollstonecraft.

Mary's mother passed away shortly after Mary was born. Her father raised her and gave her a rich education at home. He encouraged her to follow his ideas about freedom and society. When Mary was four, her father married a neighbor, Mary Jane Clairmont. Mary had a difficult relationship with her stepmother.

In 1814, Mary fell in love with Percy Bysshe Shelley, a writer who admired her father's ideas. Percy was already married at the time. With her stepsister, Claire Clairmont, Mary and Percy traveled through France and Europe. When they returned to England, Mary was expecting a child. Over the next two years, they faced difficulties, including money problems and the sad loss of their baby daughter who was born too early. They married in late 1816, after Percy's first wife, Harriet, sadly passed away.

In 1816, Mary, Percy, and Mary's stepsister spent a summer near Geneva, Switzerland. They were with Lord Byron and John William Polidori. During this time, Mary got the idea for her famous novel Frankenstein. The Shelleys moved to Italy in 1818. There, they faced more sadness with the deaths of two more of their children. Later, Mary gave birth to her only child who survived to adulthood, Percy Florence Shelley. In 1822, her husband Percy tragically died when his sailing boat sank during a storm. A year later, Mary returned to England. She then focused on raising her son and her career as a professional author. Later in her life, Mary became ill and passed away at age 53.

For many years, Mary Shelley was mainly known for publishing her husband's works and for Frankenstein. This novel is still widely read and has inspired many plays and movies. More recently, experts have learned more about Mary Shelley's achievements. They are very interested in her other books. These include the historical novels Valperga (1823) and Perkin Warbeck (1830). She also wrote The Last Man (1826), a story about the end of the world. Her last two novels were Lodore (1835) and Falkner (1837).

Studies of her less famous works, like the travel book Rambles in Germany and Italy (1844), show that Mary Shelley remained someone who believed in big changes for society throughout her life. Her writings often suggest that cooperation and kindness, especially among women in families, could improve society. This idea challenged the focus on individual freedom promoted by Percy Shelley and her father, William Godwin.

Mary Shelley's Life and Career

Early Life and Education

Mary Shelley was born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin in Somers Town, London, in 1797. She was the daughter of two famous thinkers. Her mother was Mary Wollstonecraft, a feminist writer and educator. Her father was William Godwin, a philosopher and novelist. Mary's mother passed away shortly after Mary was born.

William Godwin raised Mary and her older half-sister, Fanny Imlay. Fanny was Mary Wollstonecraft's child from a previous relationship. A year after her mother's death, Mary's father wrote a book about her. This book shared some personal details about Mary's mother that were considered surprising at the time. Mary grew up reading her mother's books and cherishing her memory.

Mary's early years were happy. However, her father was often in debt. Feeling he couldn't raise the children alone, he looked for a second wife. In December 1801, he married Mary Jane Clairmont. She was an educated woman with two young children, Charles and Claire. Many of Godwin's friends disliked his new wife, calling her quick-tempered. But Godwin was devoted to her. Mary Godwin, however, disliked her stepmother. Some believed Mrs. Godwin favored her own children.

The Godwins started a publishing company called M. J. Godwin. They sold children's books, stationery, maps, and games. The business struggled and Godwin had to borrow a lot of money. By 1809, his business was failing, and he felt very worried. Friends like Francis Place helped him by lending money, saving him from prison for not paying debts.

Mary Godwin received little formal schooling. However, her father taught her many subjects. They often went on educational trips. She could use his library and meet many smart people who visited him. These visitors included the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and former US Vice-President Aaron Burr. Mary received an unusual and advanced education for a girl of her time. She had a governess and a tutor. She read many of her father's children's books about Roman and Greek history. In 1811, she also attended a boarding school for six months. Her father described her at age 15 as "singularly bold, somewhat strong-willed, and active of mind."

In June 1812, Mary's father sent her to stay with the family of William Baxter, who had strong beliefs, near Dundee, Scotland. He wanted her to be raised "like a philosopher." Mary enjoyed the large house and the company of Baxter's four daughters. She returned for another long stay in 1813. In her 1831 introduction to Frankenstein, she remembered that her imagination grew "beneath the trees" and "on the bleak sides of the woodless mountains."

Meeting Percy Bysshe Shelley

Mary Godwin likely met the poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley between her trips to Scotland. By March 1814, Percy Shelley was living separately from his wife. He often visited William Godwin, who he had promised to help with his debts. Percy Shelley's strong beliefs about society, especially his economic ideas, came from Godwin's book Political Justice (1793). These ideas caused problems with his wealthy family. They wanted him to live like a traditional aristocrat. But he wanted to use his family's money to help those in need. Because of this, Percy Shelley had trouble getting money until he inherited his estate. After many promises, Shelley said he could not pay all of Godwin's debts. Godwin was angry and felt let down.

Mary and Percy began meeting secretly at her mother's grave. They fell in love; Mary was 16 and Percy was 21. On June 26, 1814, they shared their feelings for each other. Mary felt drawn to Shelley's "wild, intellectual, unearthly looks." To Mary's sadness, her father disapproved. He tried to stop their relationship. Around this time, Mary's father also learned that Shelley couldn't pay his debts. Mary was confused, as she admired her father. She saw Percy Shelley as someone who embodied her parents' liberal ideas. Her father had once argued that marriage was too restrictive, though he later changed his mind. On July 28, 1814, Mary and Percy secretly left for France, taking Mary's stepsister, Claire Clairmont, with them.

After convincing Mary Jane Godwin, who had followed them to Calais, that they would not return, the three traveled to Paris. They then journeyed through France, which had recently been affected by war, to Switzerland. Mary Shelley later recalled it felt like "acting in a novel." She wrote about the "distress of the inhabitants" in France, which made her hate war. As they traveled, Mary and Percy read books, kept a journal, and wrote their own stories. In Lucerne, they ran out of money and had to turn back. They returned to England on September 13, 1814.

When Mary Godwin returned to England, things were complicated. She was expecting a child. She and Percy had no money, and her father was upset and refused to see her. The couple moved into lodgings in Somers Town and later Nelson Square. They continued their intense reading and writing. They also entertained Percy Shelley's friends, like Thomas Jefferson Hogg. Percy Shelley sometimes left home to avoid people he owed money to. Their letters show how much these separations hurt them.

Mary Godwin was expecting a child and often felt unwell. She also had to deal with Percy's close friendship with Claire Clairmont, which made her feel jealous. Percy also had a son with his first wife, Harriet, born in late 1814. On February 22, 1815, Mary gave birth to a baby girl two months early. Sadly, the baby did not survive. Mary wrote to a friend about her deep sadness, saying, "My dearest Hogg my baby is dead... I am no longer a mother now."

The loss of her child caused Mary Godwin great sadness. She became pregnant again and felt better by the summer. Percy Shelley's finances improved after his grandfather's death. The couple then vacationed in Torquay and rented a cottage near Windsor Great Park. On January 24, 1816, Mary gave birth to her second child, William, nicknamed "Willmouse." In her novel The Last Man, she later imagined Windsor as a beautiful, peaceful place.

Lake Geneva and Frankenstein

In May 1816, Mary Godwin, Percy Shelley, and their son traveled to Geneva with Claire Clairmont. They planned to spend the summer with Lord Byron. Byron had recently had a relationship with Claire, and she was expecting his child. In her book History of a Six Weeks' Tour (1817), Mary described the lonely landscape as they crossed into Switzerland.

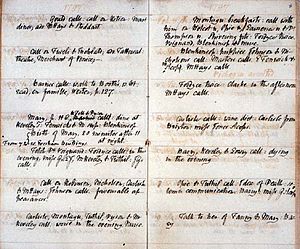

The group arrived in Geneva on May 14, 1816. Mary called herself "Mrs. Shelley." Byron joined them on May 25 with his young doctor, John William Polidori. Byron rented the Villa Diodati near Lake Geneva. Percy Shelley rented a smaller house nearby. They spent their time writing, boating, and talking late into the night.

"It was a wet, unpleasant summer," Mary Shelley remembered in 1831. "Constant rain often kept us indoors for days." Sitting by a fire at Byron's villa, they entertained themselves with German ghost stories. This led Byron to suggest they "each write a ghost story." Young Mary Godwin felt anxious because she couldn't think of a story. "Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning," she wrote, "and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative."

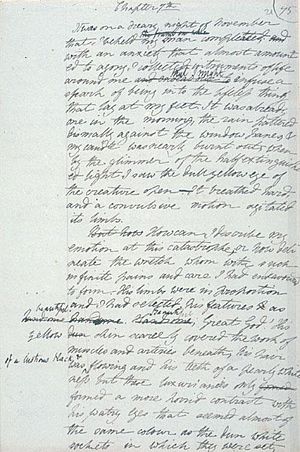

One evening in mid-June, their discussions turned to the idea of bringing things to life. "Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated," Mary thought, remembering experiments with electricity. After midnight, she went to bed but couldn't sleep. Her imagination took over, and she had a vivid "waking dream," her ghost story:

I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world.

She began writing what she thought would be a short story. With Percy Shelley's encouragement, she expanded this tale into her first novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, published in 1818. She later said that summer in Switzerland was when she "first stepped out from childhood into life." The story of how Frankenstein was written has been told many times and inspired several films.

In September 2011, astronomer Donald Olson studied the moon and stars. He concluded that Mary's "waking dream" happened "between 2am and 3am" on June 16, 1816. This was a few days after Lord Byron first suggested writing ghost stories.

Authorship of Frankenstein

Percy Shelley encouraged Mary's writing. However, the exact amount of his help with Frankenstein has been debated. Mary Shelley wrote, "I certainly did not owe the suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to my husband, and yet but for his incitement, it would never have taken the form in which it was presented to the world." She also said that the introduction to the first edition was Percy's work "as far as I can recollect."

The novel has different versions from 1818, 1823, and 1831. Some changes have been linked to Percy's editing. One scholar, James Rieger, thought Percy's help was so great that he might be seen as a co-author. However, Anne K. Mellor later argued that Percy only "made many technical corrections." Charles E. Robinson, who edited a copy of the Frankenstein manuscripts, concluded that Percy's contributions were like what most editors or colleagues might offer.

In 2018, on the 200th anniversary of Frankenstein, scholar Fiona Sampson asked why Mary Shelley hasn't received enough credit. She examined the original notebooks at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Sampson found that Percy's corrections were "rather less than any line editor working in publishing today." She shared her findings in her 2018 biography, In Search of Mary Shelley.

Life in Bath and Marlow

When Mary and Percy returned to England in September 1816, they moved to Bath. Claire Clairmont also lived nearby. They hoped to keep Claire's pregnancy a secret. In October, Mary's half-sister, Fanny Imlay, sent a worrying letter. Percy Shelley rushed to find her but couldn't. On October 10, Fanny Imlay was found dead in an inn, with a note and a bottle of medicine. On December 10, Percy Shelley's wife, Harriet, was found dead in a lake in Hyde Park, London. Both deaths were kept quiet.

Harriet's family tried to stop Percy Shelley from gaining custody of his two children with Harriet. Mary Godwin fully supported his efforts. His lawyers advised him to marry to improve his case. So, he and Mary, who was expecting another child, married on December 30, 1816. Her father gave his permission, and her parents were witnesses. This marriage helped heal the family disagreement.

Claire Clairmont gave birth to a baby girl on January 13, named Allegra. In March, a court ruled that Percy Shelley was not fit to raise his children. They were placed with a clergyman's family. Also in March, the Shelleys moved with Claire and Allegra to Albion House in Marlow, Buckinghamshire. This was a large house by the River Thames. There, Mary Shelley gave birth to her third child, Clara, on September 2. In Marlow, they hosted friends, wrote a lot, and discussed politics.

In early summer 1817, Mary Shelley finished Frankenstein. It was published without her name in January 1818. Readers thought Percy Shelley was the author because his introduction was included. Mary also edited the journal from their 1814 trip to Europe. She added notes from their 1816 visit to Switzerland and Percy's poem "Mont Blanc." This became History of a Six Weeks' Tour, published in November 1817. That autumn, Percy Shelley often lived in London to avoid people he owed money to. The fear of prison for debt, their poor health, and worries about losing their children led them to leave England for Italy on March 12, 1818. They took Claire Clairmont and Allegra with them, planning not to return.

Years in Italy

One of their first tasks in Italy was to give Allegra to Byron, who lived in Venice. He agreed to raise her if Claire had no further contact. The Shelleys then moved around, never staying in one place for long. They made many friends who often traveled with them. The couple spent their time writing, reading, learning, sightseeing, and socializing.

However, Mary Shelley's time in Italy was marked by sadness. Both her children, Clara and William, passed away. Clara died in September 1818 in Venice. William died in June 1819 in Rome. These losses left her very sad and distant from Percy Shelley. He wrote in his notebook:

My dearest Mary, wherefore hast thou gone,

And left me in this dreary world alone?

Thy form is here indeed—a lovely one—

But thou art fled, gone down a dreary road

That leads to Sorrow's most obscure abode.

For thine own sake I cannot follow thee

Do thou return for mine.

For a while, Mary Shelley found comfort only in her writing. The birth of her fourth child, Percy Florence, on November 12, 1819, finally lifted her spirits. However, she remembered her lost children throughout her life.

Italy offered the Shelleys, Byron, and other exiles a freedom they couldn't find at home. Despite the personal losses, Italy became for Mary Shelley "a country which memory painted as paradise." Their years in Italy were a time of great thinking and creativity for both Shelleys. Percy wrote many important poems. Mary wrote the novel Matilda, the historical novel Valperga, and the plays Proserpine and Midas. Mary wrote Valperga to help her father with his money problems, as Percy refused to help him further. She was often ill and prone to sadness. She also had to deal with Percy's interest in other women. Since Mary Shelley believed that marriage didn't have to be exclusive, she formed her own emotional connections with friends. She became especially fond of Prince Alexandros Mavrokordatos and of Jane and Edward Williams.

In December 1818, the Shelleys traveled south to Naples. They stayed for three months and had only one visitor, a doctor. In 1820, they faced problems from Paolo and Elise Foggi, former servants. The Foggis claimed that on February 27, 1819, Percy Shelley had registered a two-month-old baby girl, Elena Adelaide Shelley, as his child with Mary. The Foggis also said Claire Clairmont was the baby's mother. Experts have different ideas about these events. Mary Shelley insisted she would have known if Claire was pregnant. The events in Naples, a city Mary Shelley later called a "paradise inhabited by devils," remain a mystery. The only certainty is that Mary herself was not the child's mother. Elena Adelaide Shelley passed away in Naples on June 9, 1820.

After leaving Naples, the Shelleys settled in Rome. Her husband wrote that in Rome, "The voice of dead time, in still vibrations, is breathed from these dumb things." Rome inspired Mary to start writing an unfinished novel, Valerius, the Reanimated Roman. In this story, the hero fights against the decline of Rome. Her writing was interrupted when her son William died of malaria. Mary Shelley sadly noted that she came to Italy for her husband's health, but instead, the climate had killed two of her children. She wrote, "May you my dear Marianne never know what it is to lose two only and lovely children in one year." To cope with her grief, Shelley wrote the novella The Fields of Fancy, which became Matilda. This story is about a young woman whose beauty causes her father to fall in love with her. He eventually takes his own life to stop himself. The novella criticized a society where women were punished even when they did nothing wrong.

In summer 1822, Mary, who was expecting a child, moved with Percy, Claire, and Edward and Jane Williams. They went to the isolated Villa Magni, by the sea near San Terenzo. Once settled, Percy shared the sad news with Claire that her daughter Allegra had died from illness in a convent. Mary Shelley felt distracted and unhappy in the small Villa Magni, which she saw as a prison. On June 16, she had a miscarriage and lost a lot of blood. Percy quickly put her in an ice bath to stop the bleeding, which a doctor later said saved her life. That summer, things were not well between Mary and Percy. Percy spent more time with Jane Williams than with his sad and weak wife.

The coast offered Percy Shelley and Edward Williams a new sailing boat. This boat was designed by Daniel Roberts and Edward Trelawny, who had joined the group in January 1822. On July 1, 1822, Percy Shelley, Edward Williams, and Captain Daniel Roberts sailed south to Livorno. There, Percy Shelley discussed starting a magazine with Byron and Leigh Hunt. On July 8, he and Edward Williams began their return journey to Lerici with their young boat boy, Charles Vivian. They never reached their destination. A letter arrived at Villa Magni from Hunt to Percy Shelley, dated July 8, asking how they got home because of bad weather. "The paper fell from me," Mary later told a friend. "I trembled all over." She and Jane Williams rushed to Livorno and then Pisa, hoping their husbands were still alive. Ten days after the storm, they were found dead on the coast near Viareggio. Trelawny, Byron, and Hunt cremated Percy Shelley's body on the beach.

Return to England and Writing Career

"[Frankenstein] is the most wonderful work to have been written at twenty years of age that I ever heard of. You are now five and twenty. And, most fortunately, you have pursued a course of reading and cultivated your mind in a manner the most admirably adapted to make you a great and successful author. If you cannot be independent, who should be?"

After her husband's death, Mary Shelley lived for a year with Leigh Hunt and his family in Genoa. She often saw Byron and copied his poems. She decided to support herself and her son through writing. However, her financial situation was difficult. On July 23, 1823, she left Genoa for England. She stayed with her father and stepmother until her father-in-law gave her a small amount of money. Sir Timothy Shelley had first agreed to support his grandson, Percy Florence, only if he was given to a guardian. Mary Shelley refused this idea. She managed to get a small yearly allowance from Sir Timothy. However, she had to repay it later. He refused to meet her in person and only dealt with her through lawyers.

Mary Shelley worked on editing her husband's poems and other writing projects. But her concern for her son limited her choices. Sir Timothy threatened to stop the allowance if any biography of the poet was published. In 1826, Percy Florence became the legal heir to the Shelley estate. This happened after the death of his half-brother Charles Shelley. Sir Timothy increased Mary's allowance but remained difficult. Mary Shelley enjoyed the intellectual company of William Godwin's friends. However, poverty kept her from socializing as much as she wished. She also felt excluded by those who, like Sir Timothy, still disapproved of her relationship with Percy Bysshe Shelley.

On August 29, 1823, she saw a play called Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein. This was the first stage version of her novel. The play's popularity led to a second printing of Shelley's novel. Many other plays based on it also appeared. In summer 1824, Mary Shelley moved to Kentish Town in north London to be near Jane Williams. Mary was working on her novel, The Last Man (1826). She also helped friends who were writing about Byron and Percy Shelley. This was the start of her efforts to keep her husband's memory alive. She met American actor John Howard Payne and writer Washington Irving. Payne fell in love with her and asked her to marry him in 1826. She refused, saying she could only marry another genius after being married to one.

Between 1827 and 1840, Mary Shelley was busy editing and writing. She wrote the novels The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830), Lodore (1835), and Falkner (1837). She contributed five volumes of biographies of Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and French authors to Dionysius Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopaedia. She also wrote stories for women's magazines. She continued to help her father financially. In 1830, she sold the rights for a new edition of Frankenstein for £60. After her father's death in 1836, she began putting together his letters and a memoir. However, she stopped the project after two years. Throughout this time, she also promoted Percy Shelley's poetry. By 1837, Percy's works were well-known. In 1838, Edward Moxon, a publisher, suggested publishing Percy Shelley's collected works. Mary wanted to include a complete version of Percy Shelley's poem Queen Mab. Moxon wanted to leave out the most radical parts, but Mary succeeded. She was paid £500 to edit the Poetical Works (1838). Sir Timothy insisted it should not include a biography. Mary found a way to tell Percy's life story by adding detailed notes about the poems.

Mary Shelley continued to follow her mother's ideas about helping women. For example, she gave money to Mary Diana Dods, a single mother. Shelley also helped Georgiana Paul, a woman whose husband had left her. Shelley wrote in her diary about helping: "I do not make a boast... it is simple justice I perform."

Mary Shelley was careful with potential romantic partners. In 1828, she met and flirted with French writer Prosper Mérimée. She was happy when her old friend Edward Trelawny returned to England. They joked about marriage in their letters. However, their friendship changed after she refused to help with his planned biography of Percy Shelley. He later became angry when she left out the parts about atheism from Queen Mab. Her journals suggest she had feelings for politician Aubrey Beauclerk. He may have disappointed her by marrying others twice.

Mary Shelley's main concern during these years was her son, Percy Florence. She honored her late husband's wish for his son to attend a good school. With Sir Timothy's reluctant help, Percy was educated at Harrow. To save money on boarding fees, she moved to Harrow on the Hill herself. Percy went on to Trinity College, Cambridge, and studied politics and law. However, he did not show the same talents as his parents.

Final Years and Passing

In 1840 and 1842, Mary and her son traveled together in Europe. Mary Shelley wrote about these journeys in Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842 and 1843 (1844). In 1844, Sir Timothy Shelley passed away at the age of ninety. For the first time, Mary and her son were financially independent. However, the estate was not as valuable as they had hoped.

In the mid-1840s, Mary Shelley faced three separate blackmail attempts. In 1845, an Italian political exile named Gatteschi threatened to publish letters she had sent him. A friend of her son bribed a police chief to seize Gatteschi's papers, and the letters were destroyed. Soon after, Mary Shelley bought some letters written by herself and Percy Bysshe Shelley from a man pretending to be Lord Byron's son. Also in 1845, Percy Bysshe Shelley's cousin, Thomas Medwin, claimed to have written a harmful biography of Percy Shelley. He offered to suppress it for £250, but Mary Shelley refused.

In 1848, Percy Florence married Jane Gibson St John. Their marriage was happy, and Mary Shelley and Jane were fond of each other. Mary lived with her son and daughter-in-law at Field Place, Sussex, the Shelley family home, and in Chester Square, London. She also traveled with them.

Mary Shelley's last years were affected by illness. From 1839, she suffered from headaches and periods of paralysis. These sometimes prevented her from reading and writing. On February 1, 1851, she passed away at age fifty-three in Chester Square. Her doctor suspected it was a brain tumor. According to Jane Shelley, Mary Shelley had asked to be buried with her mother and father. However, Percy and Jane found the graveyard at St Pancras Old Church "dreadful." They chose to bury her instead at St Peter's Church, Bournemouth, near their new home. On the first anniversary of Mary Shelley's death, the Shelleys opened her desk. Inside, they found locks of her dead children's hair, a notebook she shared with Percy Bysshe Shelley, and a copy of his poem Adonaïs. One page was folded around a silk parcel containing some of his ashes and the remains of his heart.

Mary Shelley's Literary Themes and Styles

Mary Shelley lived a life surrounded by books and writing. Her father encouraged her to write letters. Her favorite childhood activity was writing stories. Sadly, all of Mary's early writings were lost when she left with Percy in 1814. Her first published work is often thought to be Mounseer Nongtongpaw, comic verses written for her father's children's library when she was ten. However, the poem is now linked to another writer. Percy Shelley strongly encouraged Mary Shelley's writing. She said, "My husband was, from the first, very anxious that I should prove myself worthy of my parentage, and enrol myself on the page of fame."

Novels and Autobiographical Elements

Some parts of Mary Shelley's novels are often seen as hidden stories about her own life. Critics often point to the repeated theme of a father and daughter. For example, many read Mathilda (1820) as autobiographical. They see the three main characters as versions of Mary Shelley, William Godwin, and Percy Shelley. Mary Shelley herself said she based the characters in The Last Man on her friends in Italy. Lord Raymond, who fights for the Greeks and dies, is based on Lord Byron. Adrian, Earl of Windsor, who seeks a natural paradise and dies when his boat sinks, is a fictional portrait of Percy Bysshe Shelley. However, Mary Shelley did not believe that authors "were merely copying from our own hearts." Some modern critics agree, saying her works are not just about her life.

Novelistic Genres and Styles

Mary Shelley used techniques from many different types of novels. These included the Godwinian novel, Walter Scott's historical novel, and the Gothic novel. The Godwinian novel, popular in the 1790s, explored how individuals relate to society. Frankenstein shares many themes with these novels. However, Shelley also questioned some of the ideas that Godwin promoted. In The Last Man, she used the philosophical style of the Godwinian novel to show how small humans are in the grand scheme of things. While earlier Godwinian novels showed how people could improve society, The Last Man and Frankenstein show that individuals have little control over history.

Shelley used the historical novel to comment on gender roles. For example, Valperga is a feminist version of Scott's male-focused genre. Shelley added women to the story who were not part of historical records. She used their stories to question old religious and political systems. She contrasted the male hero's desire for power with a female alternative: reason and kindness. In Perkin Warbeck, Lady Gordon represents friendship, home life, and equality. Through her, Shelley offered a feminine alternative to the destructive power struggles of the male characters. The novel provided a more inclusive historical story.

Gender and Society in Shelley's Works

With the rise of feminist literary criticism in the 1970s, Mary Shelley's works, especially Frankenstein, gained more attention. Feminist critics helped bring Shelley back into focus as a writer. Ellen Moers was one of the first to say that Shelley's loss of a baby greatly influenced Frankenstein. She argued that the novel is a "birth myth" where Shelley deals with her feelings about her mother's death and her own struggles as a parent. Scholar Anne K. Mellor suggested that, from a feminist view, Frankenstein is "about what happens when a man tries to have a baby without a woman." The novel explores the anxieties of pregnancy, birth, and motherhood.

Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar argued in their book The Madwoman in the Attic (1979) that in Frankenstein, Shelley responded to the male-dominated literary tradition. They believed Shelley both accepted and challenged this tradition. Mary Poovey saw Frankenstein as part of a pattern in Shelley's writing. This pattern started with artistic self-expression and ended with traditional femininity. Poovey suggested that Frankenstein's multiple stories allowed Shelley to express and hide herself at the same time. Shelley's fear of speaking out was reflected in Frankenstein, who was punished for his selfishness by losing his family.

Feminist critics sometimes look at how female authorship is shown in Shelley's novels. Mellor argued that Shelley used the Gothic style to explore hidden female desires and to "censor her own speech in Frankenstein." According to Poovey and Mellor, Shelley did not want to promote herself as an author. She felt unsure of her writing abilities. This feeling contributed to her fictional images of abnormality and destruction.

Shelley's writings focus on the role of the family in society and women's place within it. She celebrated the "feminine affections and compassion" linked to family. She suggested that society would fail without them. Shelley believed strongly in "cooperation, mutual dependence, and self-sacrifice." In Lodore, for example, the story follows the wife and daughter of Lord Lodore. He dies in a duel, leaving them with many challenges. The novel explores political and social issues, especially women's education and role. It criticized a society that separated genders and pushed women to depend on men. Scholar Betty T. Bennett said the novel suggests equal education for women and men. This would bring social justice and the strength to face life's challenges. Falkner is the only one of Mary Shelley's novels where the heroine's goals succeed. The novel suggests that when female values overcome violence, men will be free to show their "compassion, sympathy, and generosity."

Enlightenment and Romanticism

Frankenstein, like many Gothic stories of its time, combines shocking topics with deep, thought-provoking ideas. The novel focuses on the mental and moral struggles of the main character, Victor Frankenstein. Shelley filled the text with her own kind of political Romanticism. This criticized the individualism and selfishness of traditional Romanticism. Victor Frankenstein is like Satan in Paradise Lost and Prometheus. He rebels against tradition, creates life, and shapes his own destiny. These traits are not shown in a positive light. As scholar Jane Blumberg writes, "his relentless ambition is a self-delusion." He leaves his family to achieve his goals.

Mary Shelley believed in the Enlightenment idea that people could improve society by using political power responsibly. However, she feared that irresponsible use of power would lead to chaos. Her works often criticized how 18th-century thinkers, like her parents, believed change could happen. The creature in Frankenstein, for example, reads books about radical ideas. But the education he gains is ultimately useless. Shelley's works show her as less hopeful than Godwin and Wollstonecraft. She did not fully believe in Godwin's idea that humanity could eventually become perfect.

Scholar Kari Lokke writes that The Last Man, even more than Frankenstein, "questions our privileged position in relation to nature." It challenges the idea that humans are at the center of the universe. Mary Shelley's references to the failed French Revolution and the responses to it, challenge "Enlightenment faith in the inevitability of progress." As in Frankenstein, Shelley "offers a profoundly disenchanted commentary on the age of revolution." She rejected these political ideals and also the Romantic idea that imagination could offer an alternative.

Politics in Shelley's Writings

Recent studies emphasize Shelley as a lifelong reformer. She was deeply involved in the liberal and feminist issues of her time. In 1820, she was excited by the uprising in Spain that forced the king to grant a constitution. In 1823, she wrote articles for Leigh Hunt's magazine The Liberal. She played an active role in shaping its views. She was happy when the Whigs returned to power in 1830. She also looked forward to the Reform Act 1832.

Until recently, critics saw Lodore and Falkner as proof that Mary Shelley's later works became more conservative. In 1984, Mary Poovey suggested that Mary Shelley's reformist politics moved into the "separate sphere" of the home. Poovey thought Mary Shelley wrote Falkner to resolve her mixed feelings about her father's ideas. Mellor largely agreed, arguing that "Mary Shelley grounded her alternative political ideology on the metaphor of the peaceful, loving, bourgeois family." This view allowed women to participate in public life but kept some inequalities.

However, this view has been challenged in the last decade. For example, Bennett claims that Mary Shelley's works show a consistent commitment to Romantic ideals and political reform. Jane Blumberg's study of Shelley's early novels argues that her career cannot be easily divided into radical and conservative parts. She believes that "Shelley was never a passionate radical like her husband." She argues that Shelley was challenging the radical ideas of her circle in her first work. In this view, Victor Frankenstein's "thoughtless rejection of family" shows Shelley's constant concern for home and family.

Short Stories and Travelogues

In the 1820s and 1830s, Mary Shelley often wrote short stories for gift books or annuals. She wrote sixteen for The Keepsake, a popular magazine for middle-class women. Some have called her work in this genre "hack writing." However, critic Charlotte Sussman noted that other leading writers, like William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, also wrote for this profitable market. She explained that "the annuals were a major mode of literary production in the 1820s and 1830s."

Many of Shelley's stories are set in distant places or times, like ancient Greece or the reign of Henry IV of France. Shelley was interested in "the fragility of individual identity." She often showed how a person's role could change dramatically due to strong emotions or supernatural events. In her stories, a woman's identity was often tied to her value in the marriage market. A man's identity could be maintained through money. Although Mary Shelley wrote twenty-one short stories between 1823 and 1839, she always saw herself primarily as a novelist. She wrote to Leigh Hunt, "I write bad articles which help to make me miserable—but I am going to plunge into a novel and hope that its clear water will wash off the mud of the magazines."

When they left for France in summer 1814, Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley started a joint journal. They published it in 1817 as History of a Six Weeks' Tour. They added letters from their 1816 visit to Geneva and Percy Shelley's poem "Mont Blanc." This work celebrated young love and political ideals. It followed the example of Mary Wollstonecraft and others who combined travel with writing. The History focused on philosophical and reformist ideas, especially the effects of politics and war on France. The letters from their second journey discussed the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo. They also explored the beauty of Lake Geneva and Mont Blanc.

Mary Shelley's last full-length book was Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842 and 1843 (1844). It was written as letters and recorded her travels with her son Percy Florence and his university friends. In Rambles, Shelley followed the tradition of her mother's Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. She explored her personal and political views through kindness and understanding. For Shelley, building connections between people was key to building a good society and increasing knowledge. She wrote, "knowledge, to enlighten and free the mind...a wider circle of sympathy with our fellow-creatures;—these are the uses of travel." She included observations on scenery, culture, and politics. She also used the travelogue to reflect on her roles as a widow and mother. She visited places linked to Percy Shelley. Critic Clarissa Orr noted that Mary Shelley's philosophical mother persona gave Rambles the unity of a prose poem, with "death and memory as central themes." At the same time, Shelley argued for equality against monarchy, class differences, slavery, and war.

Biographies and Editorial Work

Between 1832 and 1839, Mary Shelley wrote many biographies of famous Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and French men and some women. These were for Dionysius Lardner's Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men. These biographies were part of Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopaedia. This was a popular series for the growing middle class who wanted to educate themselves. Until these essays were republished in 2002, their importance in her work was not fully understood. Scholar Greg Kucich said they show Mary Shelley's "amazing research across several centuries and in multiple languages." They also show her talent for biographical storytelling and her interest in feminist history. Shelley wrote in a biographical style popular in the 18th century. She combined different sources, personal stories, and her own evaluations. She recorded details of each writer's life and character. She quoted their writing and ended with a critical assessment.

For Shelley, writing biographies was meant to "form as it were a school in which to study the philosophy of history." It was also meant to teach "lessons." Most importantly, these lessons often criticized male-dominated systems, like the rule where the eldest son inherits everything. Shelley emphasized home life, romance, family, kindness, and compassion in the lives of her subjects. Her belief that these forces could improve society connected her biographical approach with other early feminist historians. Unlike her novels, which had smaller print runs, the Lives had about 4,000 copies for each volume. Kucich noted that Mary Shelley's "use of biography to forward the social agenda of women's historiography became one of her most influential political interventions."

"The qualities that struck anyone newly introduced to Shelley, were, first, a gentle and cordial goodness that animated his intercourse with warm affection, and helpful sympathy. The other, the eagerness and ardour with which he was attached to the cause of human happiness and improvement."

Soon after Percy Shelley's death, Mary Shelley decided to write his biography. In a letter from November 17, 1822, she wrote, "I shall write his life—& thus occupy myself in the only manner from which I can derive consolation." However, her father-in-law, Sir Timothy Shelley, prevented her from doing so. Mary began promoting Percy's poetry in 1824 with his Posthumous Poems. In 1839, she prepared a new edition of his poetry. This became a very important event in establishing her husband's reputation. The next year, Mary Shelley edited a volume of her husband's essays, letters, and other writings. Throughout the 1830s, she introduced his poetry to more people by publishing works in The Keepsake.

Mary Shelley often included her own notes and thoughts about her husband's life and work in these editions. This helped her avoid Sir Timothy's ban on a biography. "I am to justify his ways," she declared in 1824. "I am to make him beloved to all posterity." Scholar Jane Blumberg argued that this goal led her to present Percy's work in the "most popular form possible." To make his works suitable for a Victorian audience, she presented Percy Shelley as a lyrical poet rather than a political one. Mary explained Percy's political ideas as coming from kindness for those who suffered. She included romantic stories of his goodness, his love for home, and his appreciation for nature. She also portrayed herself as Percy's "practical muse," noting how she suggested changes as he wrote.

Despite the emotions involved, Mary Shelley proved to be a professional and scholarly editor. She worked from Percy's messy notebooks to create a timeline for his writings. She included poems, like Epipsychidion, which she would have preferred to leave out. However, she had to make compromises. Blumberg noted that "modern critics have found fault with the edition." They claim she copied incorrectly, misunderstood, or purposely changed things. According to scholar Susan J. Wolfson, modern editors still refer to Mary Shelley's editions. They acknowledge that her editing style aimed to present a full record for the general reader. Mary Shelley believed in publishing all of her husband's work. But she had to omit certain passages due to pressure from her publisher or public opinion. For example, she removed the parts about atheism from Queen Mab for the first edition. After she put them back in the second edition, her publisher was charged with blasphemy. Mary Shelley's omissions caused criticism from Percy Shelley's friends. Reviewers also accused her of including things without proper selection. Nevertheless, her notes remain an important source for studying Percy Shelley's work. Bennett explained that Mary Shelley's efforts to bring Shelley the recognition he deserved were the main reason his reputation was established.

Mary Shelley's Reputation

During her lifetime, Mary Shelley was taken seriously as a writer. However, reviewers often missed the political depth in her writings. After her passing, she was mainly remembered as Percy Bysshe Shelley's wife and the author of Frankenstein. In fact, in 1945, editor Frederick Jones wrote that a collection of her letters was justified mainly because she was Percy Bysshe Shelley's wife. This attitude continued until 1980. That's when Betty T. Bennett published the first volume of Mary Shelley's complete letters. She explained that "until recent years scholars have generally regarded Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley as a result: William Godwin's and Mary Wollstonecraft's daughter who became Shelley's Pygmalion." It wasn't until Emily Sunstein's Mary Shelley: Romance and Reality in 1989 that a full scholarly biography was published.

Mary Shelley's son and daughter-in-law tried to make her memory more "Victorian." They censored her biographical documents. This contributed to the idea that Mary Shelley was more traditional and less reform-minded than her works suggest. Her own careful omissions from Percy Shelley's works and her avoidance of public controversy also added to this impression. Comments by Hogg, Trelawny, and other admirers of Percy Shelley also tended to downplay Mary Shelley's strong beliefs. Trelawny's Records of Shelley, Byron, and the Author (1878) praised Percy Shelley at Mary's expense. It questioned her intelligence and even her authorship of Frankenstein. Lady Shelley, Percy Florence's wife, responded by publishing a heavily edited collection of letters she had inherited in 1882.

From Frankenstein's first play in 1823 to the movies of the 20th century, many people first experience Mary Shelley's work through adaptations. These include the first movie version in 1910, James Whale's famous 1931 Frankenstein, Mel Brooks' funny 1974 Young Frankenstein, and Kenneth Branagh's 1994 Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. Throughout the 19th century, Mary Shelley was seen as an author of only one novel. Most of her other works remained out of print until recently. This prevented a broader understanding of her achievements. In recent decades, almost all her writings have been republished. This has led to a new appreciation of their value. Her habit of intense reading and study, shown in her journals and letters, is now better understood. Shelley's view of herself as an author has also been recognized. After Percy's death, she wrote about her writing goals: "I think that I can maintain myself, and there is something inspiriting in the idea." Scholars now consider Mary Shelley an important Romantic figure. She is valued for her literary achievements and her political voice as a woman and a liberal thinker.

Selected Works by Mary Shelley

- History of a Six Weeks' Tour (1817)

- Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818)

- Mathilda (1819)

- Valperga; or, The Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca (1823)

- Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley (1824)

- The Last Man (1826)

- The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830)

- Lodore (1835)

- Falkner (1837)

- The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley (1839)

- Contributions to Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men (1835–39), part of Dionysius Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopaedia

- Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842, and 1843 (1844)

Collections of Mary Shelley's papers are kept in several places. These include Lord Abinger's Shelley Collection at the Bodleian Library, the New York Public Library, the Huntington Library, the British Library, and The John Murray Archive.

Mary Shelley Quotes

- "All judges had rather that ten innocent should suffer than that one guilty should escape."

- "Nothing contributes so much to tranquilize the mind as a steady purpose."

- "As a child I scribbled; and my favourite pastime, during the hours given me for recreation, was to "write stories." Still I had a dearer pleasure than this, which was the formation of castles in the air—the indulging in waking dreams—the following up trains of thought, which had for their subject the formation of a succession of imaginary incidents. My dreams were at once more fantastic and agreeable than my writings."

- "The different accidents of life are not so changeable as the feelings of human nature."

- "Invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist in creating out of void, but out of chaos."

See also

In Spanish: Mary Shelley para niños

In Spanish: Mary Shelley para niños

- Mary Shelley (2017 film)

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |