A Vindication of the Rights of Woman facts for kids

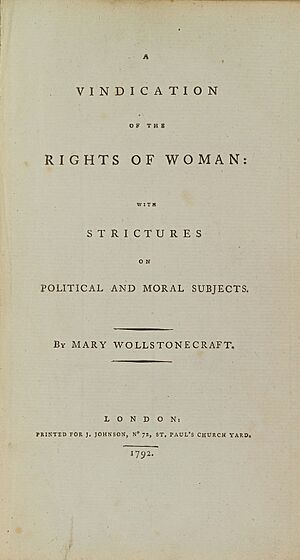

First edition title page

|

|

| Author | Mary Wollstonecraft |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Women's rights |

| Genre | Political philosophy |

|

Publication date

|

January 1792 |

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) is a famous book by the British writer Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797). It's one of the first books to talk about women's rights. In her book, Wollstonecraft argues that women should have the same kind of education as men.

During the 1700s, many thinkers believed women should only learn about managing a home. But Wollstonecraft disagreed. She said that women are important to a country because they raise children. She also believed women could be true "companions" to their husbands, not just wives who stay at home. She argued that women are human beings and deserve the same basic rights as men.

Wollstonecraft wrote Rights of Woman after reading a report by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord in 1791. This report suggested that women should only get an education for home life. Wollstonecraft was upset by this and used her book to speak out against unfair rules for women. She also criticized men for encouraging women to be overly emotional. She wrote the book quickly, planning to write a second part, but she passed away before she could finish it.

It's often thought that Rights of Woman was not liked when it first came out. But this isn't true! The book was actually well-received in 1792. One writer, Emily W. Sunstein, even called it "perhaps the most original book of [Wollstonecraft's] century." Wollstonecraft's ideas had a big impact on people who fought for women's rights later on. For example, her work influenced the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention in the United States, which was a major meeting for women's suffrage (the right to vote).

Contents

A Look Back: The Historical Context

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was written during a very exciting time. The French Revolution was happening, and people in Britain were having big debates about it. There was a lot of discussion about government, human rights, and the role of the church.

Wollstonecraft had already joined these debates in 1790 with her book A Vindication of the Rights of Men. This book was a response to Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France. Burke criticized the French Revolution, saying it was a violent overthrow of government. Wollstonecraft argued that rights shouldn't just be based on old traditions. Instead, she said rights should be given because they are fair and reasonable.

When Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord presented his ideas for national education in France, Wollstonecraft felt she had to respond. Talleyrand suggested that:

- Men should be educated for public life and the world.

- Women should be educated at home for a quiet, private life.

Wollstonecraft dedicated Rights of Woman to Talleyrand. She hoped he would think again about his ideas after reading her book. Around the same time, another French writer, Olympe de Gouges, published her own Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen. This made women's rights a central topic in both France and Britain.

Wollstonecraft's Rights of Woman built on her earlier arguments. In Rights of Men, she focused on the rights of specific men in Britain. But in Rights of Woman, she talked about the rights of "woman" in general, meaning all women, everywhere. She argued that since natural rights come from God, it's wrong for one group of people to deny them to another.

Main Ideas in the Book

Rights of Woman is a long essay that introduces its main ideas early on. Then, it keeps coming back to them from different angles. Wollstonecraft's writing style mixes logical arguments with strong, emotional language.

Understanding Sensibility

In Wollstonecraft's time, "sensibility" meant being very emotional and easily affected by things. People thought women had more "sensitive nerves" than men, so they were seen as more emotional. This idea of sensibility was also linked to being compassionate and caring.

However, by the time Wollstonecraft wrote her book, many people were starting to criticize too much sensibility. Some thought it made people weak or too focused on their own feelings. Wollstonecraft strongly criticized women who gave in to excessive sensibility. She believed these women were "blown about by every momentary gust of feeling" and couldn't think clearly. She argued that such women would harm society, not improve it. But she also believed that reason and feeling should work together.

The Importance of Rational Education

One of Wollstonecraft's most important arguments is that women should receive a rational education. This means an education that teaches them to think clearly and logically. In the 1700s, many thinkers believed women couldn't think rationally. They thought women were too emotional and fragile.

Wollstonecraft, along with other reformers, insisted that women *could* think rationally and deserved to be educated. She had already made this point in her other books, like Thoughts on the Education of Daughters and Original Stories from Real Life.

Wollstonecraft argued that if women aren't educated, society will suffer. This is especially true because mothers are the first teachers for young children. She blamed men and a "false system of education" for keeping women uneducated. She said that women only seem silly or frivolous because men have encouraged them to be that way.

She criticized writers like James Fordyce and John Gregory, and philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who said women didn't need a rational education. Rousseau, for example, argued in his book Emile that women should be educated mainly to please men. Wollstonecraft was very angry about this idea.

Wollstonecraft believed that the best education helps a person become independent and virtuous. She also proposed a specific plan for national education. She suggested that children should go to free day schools and also learn at home. She thought schooling should be co-educational, meaning boys and girls learn together. She believed that since marriage is important for society, men and women should be "educated after the same model."

Is it a Feminist Book?

It's a bit tricky to say if Rights of Woman is a "feminist" book. The words "feminist" and "feminism" didn't even exist until the 1890s! Also, there wasn't a "feminist movement" like we know it today during Wollstonecraft's time. Still, many people see Rights of Woman as a very important book for modern liberal feminism.

Wollstonecraft didn't argue for gender equality in the exact same way later feminists would. For example, she said that men and women are equal in the eyes of God. This meant they both should follow the same moral rules. While this might not seem revolutionary today, it was a big idea in the 1700s. It meant that men, not just women, should be modest and respect marriage. Wollstonecraft pointed out the unfair "double standards" of her time. She demanded that men follow the same virtues expected of women.

However, Wollstonecraft also said that men seemed designed to have "greater strength and valor." She believed that men and women were equal in important areas of life, but she didn't say they were exactly the same in every way.

Wollstonecraft also called on men to start the social and political changes she wanted. She believed that because women were uneducated, they couldn't change their situation on their own. She asked men to "generously snap our chains" and treat women as "rational companions" instead of slaves. She believed this would make women "better citizens."

Republican Ideas

Some scholars say Rights of Woman is like a "republican manifesto." This means it supports the idea of a republic, where citizens have rights and a say in government. Wollstonecraft believed that eventually, all special titles, including monarchy, should be done away with. She also suggested that all men and women should be represented in government.

Her ideas about virtue focused on individual happiness. She believed that natural rights come from God, and with those rights come duties for every person. For Wollstonecraft, people learn republican values and kindness within their families. Family relationships were very important to her idea of a strong society and patriotism.

Views on Social Class

Rights of Woman also shows Wollstonecraft's views on social classes. She mainly wrote for the middle class, which she called the "most natural state." She often praised modesty and hard work, which were seen as middle-class values at the time.

From her middle-class viewpoint, Wollstonecraft also criticized the wealthy. She said they were "weak, artificial beings" who harmed society. She believed that being rich could lead to laziness and vice.

However, her criticisms of the wealthy didn't mean she felt great sympathy for the poor. She thought the poor were lucky because they wouldn't be tempted by wealth. She also believed that charity could be negative because it kept an unequal society going.

In her plan for national education, she kept class differences. She suggested that after age nine, children meant for jobs like domestic work or trades should go to different schools. Children with "superior abilities, or fortune" would go to another school to learn languages, science, history, and politics.

Writing Style

Wollstonecraft combined different writing styles in Rights of Woman. She used the language of philosophy, calling her work a "treatise" with "arguments" and "principles." But she also used a personal tone, with "I" and "you," and emotional expressions. This created a unique voice that mixed masculine and feminine styles.

Even though she argued against too much sensibility, her writing in Rights of Woman can be very passionate. She often directed strong comments at Jean-Jacques Rousseau. For example, after quoting Rousseau, she might say, "I shall make no other comments on this ingenious passage, than just to observe, that it is the philosophy of lasciviousness." These strong statements were meant to get the reader to agree with her.

To describe the situation of women, Wollstonecraft used several comparisons. She often compared women to slaves, saying their lack of knowledge and power made them like slaves. But she also compared them to "capricious tyrants" who used tricks to control men. She argued that a woman could become either a slave or a tyrant, which she saw as two sides of the same problem. She also compared women to soldiers, saying they were valued only for their looks and obedience.

Revisions and Later Works

Wollstonecraft had to write Rights of Woman very quickly to respond to Talleyrand and current events. She later said she wasn't fully satisfied with it and wished she had more time to write a better book. When she revised the book for its second edition, she fixed small errors and also strengthened her arguments for women's rights. She changed some statements to show greater equality between men and women.

Wollstonecraft never wrote the planned second part of Rights of Woman. However, she did start writing a novel called Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman. Many scholars see this novel as a fictional follow-up to Rights of Woman. It was unfinished when she died and was published after her death by William Godwin.

See also

- "On the Equality of the Sexes"

- Timeline of Mary Wollstonecraft

Images for kids

-

Olympe de Gouges, another French feminist who wrote about women's rights around the same time.

-

The Debutante (1807) by Henry Fuseli. This painting is said to reflect Mary Wollstonecraft's ideas about how women were trapped by society.

-

The title page of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Emile (1762), a book Wollstonecraft strongly disagreed with.