Olympe de Gouges facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Olympe de Gouges

|

|

|---|---|

A painting of Olympe de Gouges from the late 1700s

|

|

| Born |

Marie Gouze

7 May 1748 Montauban, Guyenne-and-Gascony, Kingdom of France

|

| Died | 3 November 1793 (aged 45) Place de la Révolution, Paris, French First Republic

|

| Cause of death | Executed by guillotine |

| Occupation | Activist, abolitionist, women's rights advocate, playwright |

| Spouse(s) |

Louis Aubry

(m. 1765; died 1766) |

| Children | General Pierre Aubry de Gouges |

| Signature | |

Olympe de Gouges (born Marie Gouze; 7 May 1748 – 3 November 1793) was a French writer and political activist. She wrote many plays and pamphlets. Her ideas about women's rights and ending slavery were read by many people.

She started writing plays in the early 1780s. As political tensions grew in France, Olympe de Gouges became more involved in politics. In 1788, she spoke out against the slave trade in the French colonies. She also began writing political pamphlets. In her famous Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (1791), she argued against male control and the idea that men and women were not equal.

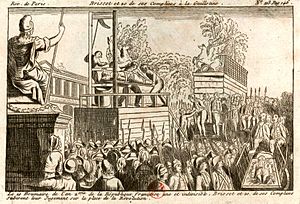

She was executed by guillotine during the Reign of Terror (1793–1794). This happened because she spoke out against the government and was linked to a political group called the Girondists.

About Olympe de Gouges

Her Early Life and Family

Marie Gouze was born on 7 May 1748 in Montauban, a town in southwestern France. Her mother, Anne Olympe Mouisset Gouze, came from a well-off family. It is not fully clear who her father was. Some believed it was her mother's husband, Pierre Gouze. Others thought she might be the daughter of a nobleman, Jean-Jacques Lefranc, Marquis de Pompignan. Marie Gouze herself encouraged these rumors. This might have been to improve her social standing.

The Pompignan family had close ties with Marie's mother's family. Pierre Gouze was legally recognized as Marie's father. He died in 1750 when Marie was only two years old.

Her Marriage and New Name

Marie Gouze received a good education and learned to read and write. Her first language was Occitan, a regional language.

On 24 October 1765, when she was seventeen, Marie was married to Louis Yves Aubry. He was a caterer. She did not want to marry him. She later wrote that she was "sacrificed" to a man she did not love. Her family's money helped Louis start his own business. In 1766, she gave birth to their son, Pierre Aubry. Just a few months later, Louis died in a flood.

Marie never married again. She called marriage "the tomb of trust and love." After her husband's death, Marie Aubry changed her name to Olympe de Gouges. She then started a relationship with a wealthy businessman named Jacques Biétrix de Rozières.

Moving to Paris and Becoming a Writer

In 1768, Biétrix helped de Gouges move to Paris. She lived there with her son and sister. She became part of the city's fashionable society. She was even called "one of Paris' prettiest women." She made friends with important people like Madame de Montesson.

De Gouges went to special gatherings called salons. These were places where writers, artists, and thinkers met to discuss ideas. She met many famous writers and future politicians there. De Gouges started her writing career in Paris. She published a novel in 1784 and then began writing many plays.

As a woman from outside Paris and not from a noble family, she worked hard to fit in. She signed her public letters with citoyenne, which is the female version of "citizen." In revolutionary France, everyone was called citoyen (citizen).

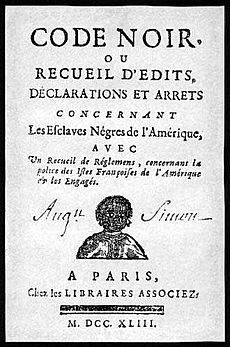

In 1788, she published a work called Réflexions sur les hommes nègres. In it, she asked for kindness for enslaved people in the French colonies. Gouges believed that there was a clear link between the king's power in France and slavery. She wrote that "Men everywhere are equal." She also said that "Kings who are just do not want slaves."

She became well-known for her play l'Esclavage des Noirs (Slavery of the Blacks). It was performed at the famous Comédie-Française theater in 1785. Because she spoke out against slavery, she received threats. Some people also criticized her for being a woman involved in theater. One influential person said that women writers were in a "false position." But Gouges was determined. She wrote, "I'm determined to be a success, and I'll do it in spite of my enemies."

The people who supported the slave trade tried to stop her play. They paid people to cause trouble during performances. The play closed after only three shows.

Her Role in Revolutionary Politics

Olympe de Gouges strongly believed in human rights. She welcomed the start of the French Revolution with hope. But she soon became disappointed. This was because "equal rights" were not given to women. In 1791, Gouges joined the "Society of the Friends of Truth." This group wanted equal political and legal rights for women.

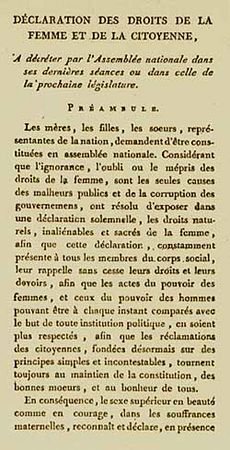

In 1791, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was written. This document gave rights to men. In response, Gouges wrote her famous Déclaration des droits de la Femme et de la Citoyenne ("Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen").

After this, she wrote her Contrat Social ("Social Contract"). This work suggested that marriage should be based on equality between men and women.

In the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), enslaved people and free people of color revolted. This happened because of the ideas in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Gouges did not support violent revolution. She published her play l'Esclavage des Noirs again in 1792. She argued that the violence used by enslaved people, even against the horrors of slavery, could be used to justify the actions of cruel rulers. The mayor of Paris accused Gouges of causing the uprising in Saint-Domingue with her play. When it was performed again in December 1792, a riot broke out in Paris.

Gouges was against the execution of Louis XVI of France, the king. She was against capital punishment (the death penalty) in general. She also preferred a constitutional monarchy, where the king's power is limited by laws. This made many strong supporters of the revolution angry.

In December 1792, when Louis XVI was about to be put on trial, she offered to defend him. This caused outrage. She argued that he was guilty as a king but innocent as a man. She believed he should be sent away instead of executed.

Gouges was connected to the Gironde faction, a political group. This group was targeted by a more extreme group called the Montagnard faction. After the king was executed, she became worried about the Montagnard faction, led by Robespierre. She openly criticized their violence and quick killings.

Her Arrest and Execution

As the Revolution continued, her writings became even stronger. On 2 June 1793, the Jacobins (part of the Montagnard faction) arrested important Girondins. They were later executed. Finally, a poster she wrote in 1793, called Les trois urnes ("The Three Urns"), led to her arrest. In this poster, Olympe called for a fair government and an end to violence. She said, "Now is the time to put a stop to assassinations." She also asked for a vote to choose one of three types of government: a single republic, a federal government, or a constitutional monarchy. The problem was that a law of the revolution made it a crime punishable by death to suggest bringing back the monarchy.

After her arrest, officials searched her house for evidence. When they found nothing, she showed them where she kept her papers. There, they found an unfinished play called La France Sauvée ou le Tyran Détroné ("France Preserved, or The Tyrant Dethroned"). In this play, Marie-Antoinette (the queen) is planning how to save the monarchy. She is confronted by revolutionary forces, including Gouges herself. The play ends with Gouges telling the queen how she should lead her people. Both Gouges and the person prosecuting her used this play as evidence in her trial. The prosecutor said it showed Gouges supported the Royalists. Gouges argued it showed she always supported the Revolution.

She was held in jail for three months without a lawyer. The judge said she was capable of defending herself. She managed to publish two more texts from prison. In one, she described her questioning. In her last work, she spoke out against the violence of the "Terror."

Olympe de Gouges had helped her son, Pierre Aubry, get a good job. He was suspended from this job after her arrest. On 2 November 1793, she wrote to him, "I die, my dear son, a victim of my love for my country and for the people."

On 3 November 1793, she was sentenced to death by the Revolutionary Tribunal. She was executed for speaking out against the government and trying to bring back the monarchy. Olympe was executed just a month after Marquis de Condorcet and three days after the Girondin leaders. Her body was buried in a common grave.

Her Impact After Death

Her execution was a warning to other women involved in politics. A politician named Pierre Gaspard Chaumette warned women about "the impudent Olympe de Gouges." He said she was the first woman to start women's political clubs and that she ignored her home duties to get involved in the Republic. He used her as an example of what could happen. However, Gouges had not actually founded the "Society of Revolutionary Republican Women." She was shown as an enemy of the natural order.

The year 1793 was a turning point for women's roles in revolutionary France. Many women in public political roles were executed, including Madame Roland and Marie-Antoinette. The new ideal for women was the "republican mother" who raised new citizens. During this time, the government banned all women's political groups. The year 1793 also marked the start of the Reign of Terror, where thousands of people were executed.

Gouges's Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen was copied many times. It influenced other women's rights writers around the world. One year after it was published, in 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft published Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Writings about women and their lack of rights became widely available.

American women began to call themselves citess or citizeness. They took to the streets to fight for equality and freedom. At the 1848 Women's Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, the Declaration of Sentiments was written. It used a similar style to Gouges's Declaration and demanded women's right to vote.

After her execution, Olympe's son, Pierre Aubry, signed a letter. In it, he said he did not support her political ideas. He tried to change her name in official records back to Marie Aubry. But the name she chose for herself, Olympe de Gouges, is the one that is remembered.

Her Writings

De Gouges's first published work in 1784 was a novel written as letters. It claimed to be real letters exchanged with her father. After this novel, de Gouges began writing plays. Her first play, Zamore et Mirza ou l’Heureux Naufrage (Zamore and Mirza; Or, The Happy Shipwreck), was performed in 1784.

Plays Before the Revolution

Gouges wrote more than 40 plays. They often focused on social issues. Many of her plays were published. Records from when she was executed in 1793 list about 40 plays. She wrote about topics like the slave trade, divorce, marriage, and children's rights. She also wrote about government programs for the unemployed. As a playwright, she often tackled important political debates of her time.

Her 1788 pamphlet Réflexions sur les Hommes Nègres and her play L'Esclavage des Noirs made her one of France's first public opponents of slavery. In her 1788 "Reflections on Black Men," she highlighted the terrible situation of enslaved people. She condemned the unfairness of slavery. She said, "I clearly realized that it was force and prejudice that had condemned them to that horrible slavery." She also stated that "Men everywhere are equal." In her play L'Esclavage des Noirs, she even had a French slave owner pray for freedom. She compared slavery in the colonies to political oppression in France. One of the enslaved characters in her play said that the French must gain their own freedom before they can deal with slavery. Gouges also openly questioned if human rights were truly real in revolutionary France.

Political Pamphlets and Letters

Throughout her career, de Gouges published 68 pamphlets. Her first political pamphlet came out in November 1788. It was called Letter to the people, or project for a patriotic fund. In early 1789, she published Remarques Patriotiques. In this work, she suggested ideas for social security, care for the elderly, and homes for homeless children. She also proposed hostels for the unemployed and a jury system. She wrote about the problems facing France before the revolution. She said, "France is sunk in grief, the people are suffering." She also called on women to "shake off the yoke of shameful slavery." That same year, she wrote many pamphlets on social issues, like children born outside of marriage. She continued to publish political essays between 1788 and 1791.

Gouges wrote her famous Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen after the French Constitution of 1791 was approved by King Louis XVI. She dedicated it to his wife, Queen Marie Antoinette. The French Constitution created a short-lived constitutional monarchy. It defined citizens as men over 25 who were "independent" and paid taxes. These men had the right to vote. Women, children, servants, and enslaved people had no political rights. Gouges argued that the constitution did not go far enough in giving rights to everyone.

Gouges was not the only woman who tried to influence politics in France. But her ideas, like those of other women, were often ignored. Important political figures at the time were not convinced that women should have equal rights.

In her early political letters, Gouges made it clear that she was speaking "as a woman." She addressed her public letters, often published as pamphlets, to important leaders like Jacques Necker or the queen Marie-Antoinette. Like other pamphlet writers, she spoke from the outside. She shared her experiences as a citizen who wanted to influence public debate. In her letters, she explained the values of the Enlightenment. She talked about how ideas like civic virtue, universal rights, and natural rights could be put into practice. These debates were mostly among men and about men. Women were not given political rights. So, Gouges used her pamphlets to join the public discussion. She argued that women's voices needed to be included.

Gouges signed her pamphlets with citoyenne. She believed that her political thoughts were important for the nation. She wrote, "This dream, strange though it may seem, will show the nation a truly civic heart."

As French politics changed, Gouges was not able to become a direct political leader. But in her letters, she offered advice to the government. She believed France should keep a constitutional monarchy.

Public letters, or pamphlets, were the main way for working-class people and women writers to join the public debate in revolutionary France. These pamphlets were often meant to stir up public anger. They were read widely inside and outside France. Gouges's contemporary, Madame Roland, became famous for her Letter to Louis XVI in 1792. In the same year, Gouges wrote Letter to Citizen Robespierre, but he refused to answer her.

Her Legacy

Olympe de Gouges was famous during her lifetime and wrote many works. But she was largely forgotten after her death. She was rediscovered through a book by Olivier Blanc in the mid-1980s.

On 6 March 2004, a square in Paris was named Place Olympe de Gouges. It was opened by the mayor of the 3rd district of Paris. The actress Véronique Genest read from the Declaration of the Rights of Woman at the event. In 2007, a French presidential candidate, Ségolène Royal, said she wished Gouges's remains could be moved to the Panthéon. However, her remains were lost in common graves, like those of other victims of the Reign of Terror. So, any reburial would only be a ceremony.

She is honored with many street names across France. There is also the Salle Olympe de Gouges exhibition hall in Paris and the Parc Olympe de Gouges in Annemasse.

The 2018 play The Revolutionists by Lauren Gunderson is about Gouges. It shows a fictionalized version of her life as a writer and activist during the Reign of Terror.

Selected Works

- Zamore et Mirza, ou l’heureux naufrage (Zamore and Mirza, or the Happy Shipwreck) 1784

- Le Mariage inattendu de Chérubin (The Unexpected Marriage of Cherubin) 1786

- L’Homme généreux (The Generous Man) 1786

- Molière chez Ninon, ou le siècle des grands hommes (Molière at Ninon, or the Century of Great Men) 1788

- Les Démocrates et les aristocrates (The Democrats and the Aristocrats) 1790

- La Nécessité du divorce (The Necessity of Divorce) 1790

- Le Couvent (The Convent) 1790

- Mirabeau aux Champs Élysées (Mirabeau at the Champs Élysées) 1791

- La France sauvée, ou le tyran détrôné (France saved, or the Dethroned Tyrant) 1792

- L'Entrée de Dumouriez à Bruxelles (The Entrance of Dumouriez in Brussels) 1793

See also

In Spanish: Olympe de Gouges para niños

In Spanish: Olympe de Gouges para niños

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of women's rights activists

- The Women's March on Versailles

- Women's Petition to the National Assembly

Portrayals

- “Flashback” released November 2021

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |