Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen facts for kids

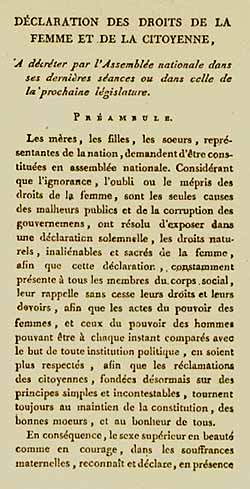

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (in French: Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne) is also known as the Declaration of the Rights of Woman. A French activist, feminist, and writer named Olympe de Gouges wrote it on September 14, 1791. She wrote it because of the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

By sharing this document on September 15, Olympe de Gouges wanted to show how the French Revolution had failed. It did not fully recognize gender equality. Because of her writings, including this Declaration, de Gouges was seen as a threat. She faced serious consequences, including execution, for her political writings.

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman is very important. It drew attention to issues that later became known as feminist concerns. These ideas reflected and influenced many people during the French Revolution.

Contents

Historical Background of Women's Rights

Early Efforts for Equal Rights

The National Constituent Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789. This happened during the French Revolution. The Marquis de Lafayette helped create this declaration. It stated that all men "are born and remain free and equal in rights." It also said these rights were for everyone.

This Declaration became a key document for human rights. It showed how some laws treated people differently based on their sex, race, or religion. In 1791, new parts were added to the French constitution. These gave civil and political rights to Protestants and Jews, who had faced unfair treatment before.

In 1790, Nicolas de Condorcet and Etta Palm d'Aelders tried to get the National Assembly to give women civil and political rights. But their efforts were not successful. Condorcet famously said that anyone who votes against another's rights, no matter their religion, color, or sex, gives up their own rights.

Women's March and Petitions

In October 1789, women in Paris protested the high price and lack of bread. They marched to Versailles. This event is often called the Women's March on Versailles. While it wasn't just about women's rights, the marchers believed that equality for all French citizens would include women. Even though the king accepted changes from the Revolution, the leaders did not recognize the women's role. They did not extend natural rights to women.

In November 1789, a group of women sent a petition to the National Assembly. They asked for equal rights for women. This was in response to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Assembly's failure to recognize women's rights. Many petitions were sent, but this one was never discussed.

The French Revolution did not immediately lead to women getting their rights. This led Olympe de Gouges to publish her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen in early 1791.

Olympe de Gouges: A Voice for Change

Olympe de Gouges was a French writer and political activist. Her writings supported women's rights and ending slavery. She started writing plays in the early 1780s. As the French Revolution grew, she became more involved in politics.

In 1788, she wrote Réflexions sur les hommes négres. This work called for kindness towards enslaved people in French colonies. De Gouges believed there was a link between the king's power in France and slavery. She argued that "Men everywhere are equal." Her play l'Esclavage des Noirs was performed in 1785.

De Gouges wrote her famous Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen after the French Constitution of 1791 was approved. She dedicated it to Queen Marie Antoinette. The new constitution created a constitutional monarchy. It defined citizens as men over 25 who were "independent" and paid taxes. These men could vote. Women, like children and servants, did not have any political rights. De Gouges argued that the constitution did not go far enough. She then wrote her Contrat Social (Social Contract), suggesting marriage should be based on gender equality.

Understanding the Declaration

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen came out on September 15, 1791. It was based on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen from 1789. Olympe de Gouges dedicated her text to Marie Antoinette. De Gouges stated that "This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society."

Her Declaration follows the seventeen articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man point by point.

A Call for Fairness

De Gouges starts her Declaration with a powerful question: "Man, are you capable of being fair? A woman is asking: at least you will allow her that right. Tell me? What gave you the sovereign right to oppress my sex?" She asks readers to look at nature. In other animal species, males and females live together peacefully. She wonders why humans cannot do the same. She asks the National Assembly to make her Declaration a part of French law.

Preamble: Women's Natural Rights

In the introduction to her Declaration, de Gouges uses similar words to the Declaration of the Rights of Man. She explains that women, just like men, have natural, unchanging, and sacred rights. She says that political groups exist to protect these rights. She ends the introduction by stating that women, "the sex that is superior in beauty as it is in courage during the pains of childbirth," recognize and declare these Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen.

Key Articles of the Declaration

Article I: Equality at Birth

The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man says, "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights." De Gouges's first article for women responds: "Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights."

Article IV: Ending Tyranny

Article IV states that "the only limit to the exercise of the natural rights of woman is the perpetual tyranny that man opposes to it." It adds that "these limits must be reformed by the laws of nature and reason." De Gouges is saying that men have unfairly stopped women's natural rights. These limits must change to create a fair society that protects everyone's natural rights.

Article VI: Equal Access to Public Roles

De Gouges expands the sixth article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man. It said citizens could help make laws. She adds: "All citizens including women are equally admissible to all public dignities, offices and employments, according to their capacity, and with no other distinction than that of their virtues and talents." This means women should have equal chances for public jobs based on their skills.

Article X: Right to Speak and Be Heard

In Article X, de Gouges points out that women could be punished by French law but were denied equal rights. She famously declared: "Women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker's rostrum." This means if women can be executed, they should also have the right to speak publicly.

Article XI: Identifying a Child's Father

De Gouges states in Article XI that a woman should be allowed to name the father of her child. Some historians believe this might relate to de Gouges's own childhood. This article would allow women to ask for support from the fathers of children born outside of marriage.

Article XII: Benefits for Society

This article explains that giving women these rights helps all of society, not just women. De Gouges believed this article would show men the good they would get from supporting the Declaration.

Article XVII: Equality in Marriage

The seventeenth article talks about equal rights in marriage. It says that in marriage, women and men are equal under the law. This means that if a couple divorces, property should be split fairly. Also, women's property cannot be taken without good reason, just like men's property.

Postscript: A Call to Women

De Gouges begins her postscript with a strong message: "Woman, wake up; the tocsin of reason is resounding throughout the universe: acknowledge your rights." She asks women to think about what they gained from the Revolution. She says it was "a greater scorn, a greater disdain." She believes men and women have much in common. She urges women to "unite under the banner of philosophy." She states that women can overcome any challenges they face and move forward in society. She also describes marriage as "the tomb of trust and love." She asks men to think about what is right when planning education for women.

De Gouges then suggests a social contract for men and women. She discusses the legal details and equality in marriage. She reshapes Rousseau's Social Contract to focus on gender equality. This creates conditions for both men and women to thrive.

De Gouges believed that fixed social classes harmed governments. She thought that a government needed a balance of power and shared good values to be healthy. This matched her support for a constitutional monarchy. She believed marriages should be voluntary unions between equal partners who share property and children. All children from these unions should have the right to both their mother's and father's names.

Reactions to the Declaration

After the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen was published, many leaders of the Revolution suspected de Gouges of treason. The Jacobins, led by Robespierre, thought de Gouges and her allies were loyal to the King and Queen. De Gouges tried to suggest a vote to choose between three types of government, including a constitutional monarchy. The Jacobins quickly tried and found her guilty of treason. She was executed by the guillotine. She was one of many "political enemies" during the Reign of Terror in France.

At the time of her death, the Parisian newspapers no longer saw her as harmless. While journalists said her plans for France were not practical, they also noted she wanted to be a "statesman." The Feuille du Salut public reported that her crime was that she had "forgotten the virtues which belonged to her sex." In Paris, during this time, her support for women's rights and her "political meddling" were seen as dangerous.

De Gouges strongly criticized the idea of equality in Revolutionary France because it ignored many people. She worked to claim the rightful place of women and enslaved people. By writing many plays about the rights of Black people and women's suffrage, her ideas spread throughout France, Europe, and the new United States of America.

Impact in Other Countries

United Kingdom's Response

In the UK, Mary Wollstonecraft was inspired to write A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects in 1792. She wrote this because of de Gouges's Declaration. She also responded to Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord's 1791 speech to the French National Assembly, which said women should only get a home-based education. Wollstonecraft's book criticized unfair standards for men and women.

Unlike de Gouges, Wollstonecraft called for equality in specific areas of life. She did not always say men and women were completely equal. Her ideas were generally well received in England in 1792.

Influence in the United States

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen did not have an immediate effect in the United States. However, it was widely used as a model for the Declaration of Sentiments. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others wrote this document at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. The Declaration of Sentiments, like de Gouges's Declaration, was written in the style of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This, in turn, was written in the style of the United States Declaration of Independence.

See also

In Spanish: Declaración de los Derechos de la Mujer y de la Ciudadana para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |