Carl Wilhelm Scheele facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Carl Wilhelm Scheele

|

|

|---|---|

Carl Scheele

|

|

| Born | 9 December 1742 Stralsund, Swedish Pomerania

|

| Died | 21 May 1786 (aged 43) Köping, Sweden

|

| Nationality | German-Swedish |

| Known for | Discovered oxygen (independently), molybdenum, manganese, barium, chlorine, tungsten and more |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (born December 9, 1742 – died May 21, 1786) was a brilliant chemist from Swedish Pomerania. He worked as a pharmacist and made many important discoveries.

Scheele found oxygen, even though others published their findings first. He also identified several elements like molybdenum, tungsten, barium, hydrogen, and chlorine. He discovered many organic acids, such as tartaric, oxalic, uric, lactic, and citric acids. He also found hydrofluoric, hydrocyanic, and arsenic acids. Scheele spoke German his whole life, as it was common among pharmacists in Sweden.

Contents

Who Was Carl Wilhelm Scheele?

Carl Scheele was born in Stralsund. This area was part of Swedish territory at the time. His father, Joachim Christian Scheele, was a grain dealer and brewer. His mother was Margaretha Eleanore Warnekros.

When Carl was young, friends of his parents taught him about prescriptions and chemical symbols. At age 14, in 1757, he became an apprentice pharmacist in Gothenburg. He worked for Martin Andreas Bauch for eight years. During this time, he spent many nights doing experiments. He also read books by famous chemists like Nicolas Lemery and Georg Ernst Stahl. Stahl's ideas about the phlogiston theory greatly influenced Scheele.

In 1765, Scheele worked in Malmö for a skilled apothecary named C. M. Kjellström. There, he met Anders Jahan Retzius, a chemistry professor. Scheele then moved to Stockholm around 1767 and continued working as a pharmacist. In Stockholm, he discovered tartaric acid. He also studied how quicklime relates to calcium carbonate with his friend Retzius.

Scheele's Work in Uppsala and Köping

In 1770, Scheele became the director of a large pharmacy laboratory in Uppsala. This lab supplied chemicals to Professor Torbern Bergman. Scheele and Bergman became friends after Scheele helped solve a tricky chemical reaction. This reaction involved heated saltpetre and acetic acid, which produced a red vapor. Studying this reaction later helped Scheele discover oxygen.

Because of their friendship, Bergman allowed Scheele to use his laboratory freely. Both chemists benefited from this partnership. In 1774, Scheele was chosen to be a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. He was officially elected on February 4, 1775. That same year, Scheele briefly managed a pharmacy in Köping. By late 1776, he opened his own pharmacy business there.

On October 29, 1777, Scheele attended his first and only meeting at the Academy of Sciences. A few weeks later, he passed his apothecary exam with the highest honors. After returning to Köping, he focused on his scientific research. This led to many important discoveries.

The famous writer Isaac Asimov called Scheele "hard-luck Scheele." This was because Scheele made many discoveries that others got credit for first.

Understanding Gases and Phlogiston

When Scheele was young, the main idea about how things burned was the phlogiston theory. This theory said that a substance called "phlogiston" (like "matter of fire") was released when something burned. When all the phlogiston was gone, the burning would stop.

Scheele discovered oxygen and called it "fire air." He noticed it helped things burn. He used the phlogiston theory to explain oxygen. He didn't think his discovery proved the phlogiston theory wrong.

Before finding oxygen, Scheele studied air. People thought air was a simple element that didn't affect chemical reactions. Scheele's research showed that air was a mixture of "fire air" (oxygen) and "foul air" (nitrogen). He heated many substances like potassium nitrate, manganese dioxide, and mercuric oxide. In all these experiments, he found the same gas: his "fire air." He believed this "fire air" combined with phlogiston during burning.

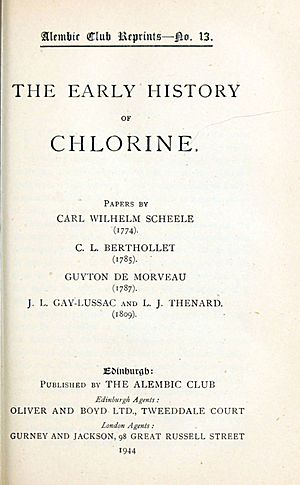

Scheele finished writing about his oxygen discovery in 1775. His book, Chemische Abhandlung von der Luft und dem Feuer, was published in 1777. However, Joseph Priestley and Antoine Lavoisier had already published their findings about oxygen by then. So, Scheele is often credited along with them for discovering oxygen.

Scheele's Important Discoveries

Scheele made amazing discoveries even without expensive lab equipment. His work, along with that of Lavoisier and Priestley, helped make chemistry a more organized science. Although Scheele didn't fully understand the importance of his oxygen discovery, his work was key to moving past the old phlogiston theory.

Scheele's study of oxygen began when Professor Torbern Bergman asked him about a problem. Bergman noticed that saltpeter, after being heated, produced red vapors when mixed with acetic acid. Scheele quickly explained this using the phlogiston theory.

Bergman then suggested Scheele study manganese(IV) oxide. Through this study, Scheele developed his idea of "fire air" (oxygen). He got oxygen by heating mercuric oxide, silver carbonate, magnesium nitrate, and other salts. He wrote to Lavoisier about his findings, and Lavoisier understood their importance. Scheele found oxygen around 1771, earlier than Priestley or Lavoisier. But he published his discovery in 1777, after them.

Scheele always believed in some form of the phlogiston theory. However, his work simplified it. He thought that hydrogen was made of phlogiston plus heat. He also believed that his "fire air" (oxygen) combined with phlogiston to create light or heat.

New Elements and Compounds

Besides oxygen, Scheele is also credited with discovering other chemical elements. These include barium (1772), manganese (1774), molybdenum (1778), and tungsten (1781). He also found many chemical compounds. Some of these are citric acid, lactic acid, glycerol, hydrogen cyanide (also called prussic acid), hydrogen fluoride, and hydrogen sulfide (1777).

Scheele also found a way to mass-produce phosphorus in 1769. This helped Sweden become a top producer of matches.

In 1774, Scheele made another very important discovery. He was studying a rock called pyrolusite (impure manganese dioxide). He found lime, silica, and iron in it. But he also found a new part, which was manganese. He couldn't isolate the pure manganese, but he knew it was a new element.

When he mixed pyrolusite with hydrochloric acid and heated it, a yellow-green gas with a strong smell appeared. He noticed this gas was heavier than air and sank in an open bottle. It didn't dissolve in water. This gas turned corks yellow and removed color from wet blue litmus paper and some flowers. He called it "dephlogisticated muriatic acid." Later, Sir Humphry Davy named this gas chlorine, because of its pale green color.

Chlorine's ability to bleach led to a new industry. It also became important for disinfecting and cleaning wounds.

Scheele's Final Years

In late 1785, Scheele started feeling unwell. In early 1786, he became very weak. Knowing he might not live long, he married the widow of the pharmacy's previous owner. He did this so she would inherit his pharmacy and belongings.

Scheele's experiments often involved dangerous chemicals. Like many chemists of his time, he would smell and taste new substances to learn about them. He worked with heavy metals like arsenic, mercury, and lead, and also hydrofluoric acid. Over time, being exposed to these substances took a toll on his health.

Carl Wilhelm Scheele died at the age of 43 on May 21, 1786, in his home in Köping. Doctors believed he died from mercury poisoning.

Published Works

Scheele published many important papers over 15 years. His work first appeared in the Transactions of the Swedish Academy of Sciences. It was also in other science magazines, like Lorenz Florenz Friedrich von Crell's Chemische Annalen.

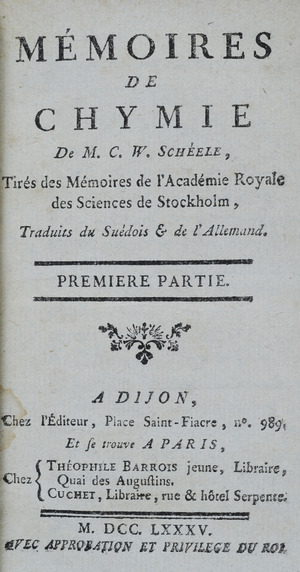

Scheele's writings were later collected and published in four languages. Mémoires de Chymie was a French translation by Mme. Claudine Picardet in 1785. Chemical Essays was an English translation by Thomas Beddoes in 1786. Later, his works were also translated into Latin and German. Another English translation was made by Dr Leonard Dobbin in 1931.

See also

In Spanish: Carl Wilhelm Scheele para niños

In Spanish: Carl Wilhelm Scheele para niños

- Scheelite

- Scheele's Green

- Pharmacist

- Pharmacy

- Pneumatic chemistry

- List of independent discoveries

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |