Georg Ernst Stahl facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Georg Ernst Stahl

|

|

|---|---|

Georg Ernst Stahl

|

|

| Born | 22 October 1659 |

| Died | 24 May 1734 (aged 74) Berlin, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Jena |

| Known for | Phlogiston theory Fermentation |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | University of Halle |

| Influences | J. J. Becher |

Georg Ernst Stahl (born October 22, 1659 – died May 24, 1734) was an important German chemist, physician, and philosopher. He believed in something called vitalism, which means he thought living things had a special "life force." For many years, his ideas about the phlogiston theory helped explain how chemical reactions worked.

Contents

About Georg Ernst Stahl

Georg Ernst Stahl was born on October 22, 1659, in Ansbach, which is now part of Germany. His father was a pastor, so Georg grew up in a very religious home. From a young age, he was very interested in chemistry. By the time he was 15, he had already studied advanced chemistry notes and books.

He studied medicine at the University of Jena in the late 1670s. He was very good at his studies and earned his medical degree around 1683. After that, he started teaching at the same university.

His teaching skills became well-known. In 1687, he was hired as the personal doctor for Duke Johann Ernst of Sachsen-Weimar. Later, in 1693, he joined his friend Friedrich Hoffmann at the University of Halle. A year later, in 1694, he became the head of medicine there. From 1715 until he passed away, he worked as the doctor and advisor to King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia in Berlin. He was also in charge of Berlin's Medical Board.

Stahl's Ideas on Medicine

Stahl was very interested in what makes living things different from non-living things. He thought that non-living things stay mostly the same over time. But living things are always changing and can break down, which led him to study fermentation.

He believed that living things have a special force, or "soul" (called anima), that stops them from breaking down quickly. This anima controlled all the body's processes. He thought it guided how the body worked, not just how its parts moved. He saw three main movements in the body: blood circulation, excretion (getting rid of waste), and secretion (making useful substances).

Stahl thought that doctors should treat the whole person, including their anima, not just separate body parts. He felt that knowing only about the body's mechanical parts was not enough.

Tonic Motion and Health

As a doctor, Stahl focused on the anima and how blood moved in the body, which he called "tonic motion." He believed that if the anima worked well, a person would be healthy. If it didn't, then illness would happen.

Tonic motion was about the contracting and relaxing movements of body tissues. Stahl thought this motion helped explain how animals create heat and how fevers happen. In his 1692 paper, De motu tonico vitali, he explained how tonic motion was connected to blood flow.

Stahl's theory of tonic motion also explained how muscles in the circulatory system worked. He saw patients with headaches and nosebleeds. He thought these happened when blood needed a way to flow if a body part was blocked or injured. He also studied menstruation and believed that bloodletting (removing blood) from the upper body could help with bleeding during a period.

Stahl's Work in Chemistry

Stahl did his best chemistry work while teaching at Halle. Like medicine, he believed that chemistry could not be fully explained by just looking at mechanical parts. He thought that atoms existed but that simply studying them wasn't enough to understand chemical processes. He believed atoms joined together to form elements. He used a hands-on approach to describe chemistry.

Stahl was influenced by the work of Johann Joachim Becher. From Becher, Stahl developed his famous phlogiston theory. Before Stahl, this theory didn't have much experimental proof. Becher had suggested that a substance called terra pinguis escaped during burning.

Stahl built on this idea. He proposed that metals were made of "calx" (like ash) and phlogiston. When a metal was heated, the phlogiston would leave, and only the calx would remain. He made this theory useful for chemistry, and it became one of the first big ideas to connect different chemical reactions. Phlogiston theory helped explain many chemical events and encouraged chemists to explore the subject more.

Even though Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier later replaced this theory with the idea of oxidation, Stahl's phlogiston theory is seen as a bridge between old alchemy and modern chemistry. Stahl also had ideas about fermentation that were similar to those of Justus Liebig much later.

Stahl is also known for being one of the first to describe carbon monoxide in 1697. He called it noxious carbonarii halitus, meaning "harmful carbonic vapors."

Works

- Zymotechnia fundamentalis (1697)

- De lumbricis terrestribus eorumque usu medico (1698)

- Disquisitio de mechanismi et organismi diversitate (1706)

- Paraenesis, ad aliena a medica doctrine arcendum (1706)

- De vera diversitate corporis mixti et vivi (1706)

- Theoria medica vera (1708)

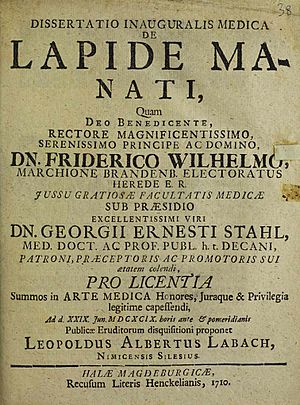

- De lapide manati (1710)

- Georgii Ernesti Stahlii opusculum chymico-physico-medicum (1715)

- Specimen Beccherianum (1718)

- Philosophical Principles of Universal Chemistry (1730)

- Experimenta, observationes, animadversiones, 300. numero, chymicae et physicae (1731)

- Materia medica (1744)

- Fundamenta chymiae (1746-1747)

- The Leibniz-Stahl Controversy (2016)

See also

In Spanish: Georg Stahl para niños

In Spanish: Georg Stahl para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |