Claudine Picardet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Claudine Picardet

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait detail, believed to be Mme. Picardet

|

|

| Born |

Claudine Poullet

7 August 1735 Dijon, France

|

| Died | 4 October 1820 (aged 85) Paris

|

| Nationality | French |

| Other names | Claudine Guyton de Morveau |

| Spouse(s) |

|

Claudine Picardet (born Poullet, later Guyton de Morveau) (August 7, 1735 – October 4, 1820) was a very important French scientist. She was a chemist, a mineralogist (someone who studies minerals), a meteorologist (someone who studies weather), and a scientific translator.

She was known for translating many scientific books and papers. She translated from Swedish, English, German, and Italian into French. This helped spread new scientific ideas across France. Claudine also hosted popular gatherings called "salons" in Dijon and Paris. At these salons, scientists and writers discussed new discoveries. She also actively collected weather data. Her work helped make Dijon and Paris important centers for science. She played a big part in sharing scientific knowledge during a time of major changes in chemistry.

Contents

Biography of Claudine Picardet

Claudine Poullet was born in Dijon, France. She was the oldest daughter of a royal notary, François Poulet de Champlevey. In 1755, she married Claude Picardet, who was a lawyer. Her husband was also a member of the Dijon Academy of Sciences. This helped Claudine meet many important people in science and high society.

She went to scientific talks and demonstrations. Soon, she became active as a scientist, a "salonnière" (someone who hosts salons), and a translator. At first, her published works only used the name "Mme P*** de Dijon." Claudine and Claude had one son, but he sadly died at age 19 in 1776.

After her husband died in 1796, Claudine moved to Paris. In 1798, she married Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau. He was a close friend and fellow scientist for many years. Guyton de Morveau was a leader in the French government and a chemistry professor. Claudine kept doing her translations and scientific work. She also continued to host famous scientific salons. During the time of Napoleon, she was known as Baroness Guyton-Morveau.

An observer once said about her:

“Madame Picardet is as agreeable in conversation as she is learned in the closet; a very pleasing unaffected woman; she has translated Scheele from the German, and a part of Mr. Kirwan from the English; a treasure to M. de Morveau, for she is able and willing to converse with him on chymical subjects, and on any others that tend either to instruct or please.”

Not much is known about her life after her second husband died in 1816, until her own death in 1820.

Claudine Picardet's Important Translations

Claudine Picardet translated thousands of pages of scientific writings. Many of these were by the top scientists of her time. She translated from several languages so they could be published in French. Her work was part of a new way of doing scientific translation. Instead of one person working alone, groups of translators started working together.

Guyton de Morveau led a group of translators at the Dijon Academy. This group was called the Bureau de traduction de Dijon. They worked to quickly translate foreign science texts, especially in chemistry and mineralogy. This "team effort" needed people with connections to get the original books. It also needed people with language skills and scientific knowledge to make sure the translations were correct.

Besides translating words, they also did experiments in the lab. They would repeat the experiments described in the original texts to check the results. They also observed minerals closely, noting their color, smell, and crystal shape. This helped them confirm the facts in the original writings.

The Dijon Academy group was a "pioneering" team. They made the work of foreign scientists available in France. Some translations were published in books and journals. Others were shared as handwritten copies among scientists and friends. They also presented experiments at public talks. Claudine Picardet was special in this group. She was the only person who was not an academic (a university scholar). She was also the only woman. And she translated more than any of the half-dozen men in the group. She was the only one who worked in five languages. She also published in journals other than the Annales de chimie. This journal was started by Guyton de Morveau, Antoine Lavoisier, and others in 1789.

Some writers later tried to give credit for Picardet's work to Guyton de Morveau and others. But a historian named Patrice Bret says this was unfair and wrong. The published works and other evidence show that Claudine Picardet did the work herself.

Key Works Translated by Picardet

By 1774, Claudine Picardet was translating a book by John Hill about minerals. It was called Spatogenesia. She became a major contributor to a journal called Journal de physique. Her early works only used "Mme. P" or "Mme P*** de Dijon" to identify her. By 1782, letters from Guyton de Morveau showed that Claudine Picardet had translated works from English, Swedish, German, and Italian.

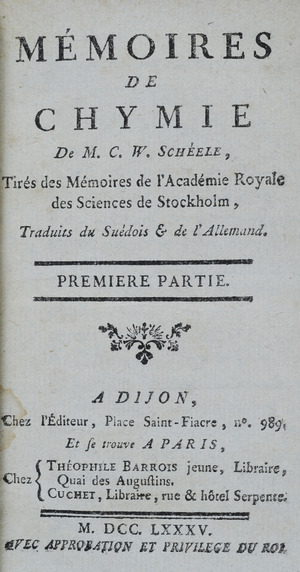

Picardet created the first published collection of chemistry papers by Carl Wilhelm Scheele. She translated them from Swedish and German. This collection was called Mémoires de chymie de M. C. W. Scheele (Memoirs of Chemistry by Mr. C. W. Scheele). It came out in two volumes in 1785. Madame Picardet is given credit for making Scheele's important work on oxygen known to scientists in France. She was publicly named as a translator for the first time in a review of this book in 1786.

Picardet also wrote the first translation of Abraham Gottlob Werner's 1774 book. This book was called Von den äusserlichen Kennzeichen der Fossilien (On the External Characters of Fossils, or of Minerals). It was the first modern textbook on describing minerals. It included a detailed color system to describe and classify them. Picardet's translation was called Traité des caractères extérieurs des fossiles (Treatise on the external characteristics of fossils). It was published in Dijon in 1790. Her translation was so expanded and had so many notes that it's often seen as a new edition of the book.

In both of these translations, any parts added by other authors were clearly marked.

Some historians believe Picardet did most of a French translation of the first two volumes of Torbern Olof Bergman’s Opuscula physica et chemica. This Latin work was published as Opuscules chymiques et physiques de M. T. Bergman (Chemical and Physical Works of Mr. T. Bergman). It was generally credited to Guyton de Morveau. But letters suggest Picardet and others helped translate Bergman's works without getting credit.

Madame Picardet is also said to have inspired and possibly helped write Madame Lavoisier's translation and critique of Richard Kirwan's 1787 Essay on Phlogiston. Phlogiston was an old idea about how things burn. Picardet translated some of Kirwan's other papers too.

Claudine Picardet translated scientific papers from many languages. These included Swedish (Scheele, Bergman), German (Wiegleb, Westrumb, Meyer, Klaproth), English (Kirwan, Fordyce), and Italian (Landriani). She mostly translated works on chemistry and mineralogy. But she also translated some works about weather.

Claudine Picardet's Scientific Work

Picardet took chemistry classes from Morveau. She also studied the minerals in the Dijon Academy's collection. With Guyton de Morveau and other members of the translation group, she did chemistry experiments. She also made observations of minerals to check the information in the works they were translating. The introduction to her translation of Werner's book on minerals clearly states that she was skilled at lab work and observations. She even created her own French words to describe minerals based on her direct observations.

Picardet was also part of Antoine Lavoisier’s group that collected weather data. Starting in 1785, she took daily barometric observations (measurements of air pressure). She used an instrument from the Dijon Academy. Madame Picardet sent her results to Lavoisier. These results were then shared with the French Academy of Sciences in Paris.

Portrait of Scientists

Around 1782, Guyton de Morveau suggested a new way to name chemicals. He thought simple substances should have simple names that showed their chemical structure, like hydrogen and oxygen. Compounds should have names that showed what they were made of, like sodium chloride and ferric sulfate.

From 1786 to 1787, Guyton de Morveau, Antoine Lavoisier, Claude-Louis Berthollet, and Antoine-François Fourcroy met almost every day. They worked hard to write a book called Méthode de nomenclature chimique (Method of Chemical Nomenclature). Their goal was to completely change how names were given to chemicals that don't contain carbon.

A famous painting of Lavoisier with the co-authors of this book is believed to include both Madame Lavoisier and Madame Picardet. Madame Lavoisier is on the left side of the group. The woman next to her is thought to be Madame Picardet. She is holding a book, which represents her important work as a translator.

Claudine Picardet's Impact on Science

Because of the work of both Claudine Picardet and her second husband, Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau, Dijon became known around the world as a science center. Madame Picardet was one of the two most active translators in chemistry during the 1780s. She made a lot more chemical knowledge available at a very important time. This was during the chemical revolution, especially knowledge about salts and minerals.

Her work helped new science journals get published. It also helped set up important features in journals, like showing the date when an article was first published. Scientists of her time, both in France and other countries, recognized how valuable her translation work was.

Images for kids

-

Mme. Lavoisier (left), Claudine Picardet (with book), Berthollet, Fourcroy, Lavoisier (seated) and Guyton de Morveau (right)

See also

In Spanish: Claudine Picardet para niños

In Spanish: Claudine Picardet para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |