Marie-Anne Paulze Lavoisier facts for kids

Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze Lavoisier (born January 20, 1758, in Montbrison, Loire, France – died February 10, 1836) was an important French chemist and noblewoman. She was married to the famous chemist Antoine Lavoisier. Marie-Anne worked closely with her husband in his laboratory, helping him with his experiments. She also translated many scientific books and helped make the scientific method better.

Contents

Her Early Life and Marriage

Marie-Anne's father, Jacques Paulze, was a lawyer and financier. He earned money by running the Ferme Générale, a group that collected taxes for the French king. Her mother, Claudine Thoynet Paulze, died when Marie-Anne was only three years old. After her mother's death, Marie-Anne went to live in a convent where she received her education.

When Marie-Anne was just thirteen, a 50-year-old count wanted to marry her. Her father did not want this marriage to happen. To stop it, he asked his colleague, Antoine Lavoisier, to marry Marie-Anne instead. Lavoisier was a French nobleman and scientist. He agreed, and they were married on December 16, 1771. Marie-Anne was about 13, and Lavoisier was about 28.

Working in the Lab

In 1775, Lavoisier became an administrator for gunpowder. This meant the couple moved to the Arsenal in Paris. Here, Lavoisier built a very modern chemistry laboratory. Marie-Anne soon became very interested in his scientific work. She started helping him actively in the lab.

She even received special training in chemistry from Lavoisier's colleagues. The Lavoisiers spent most of their time together in the laboratory. They worked as a team on many different research projects. Marie-Anne also helped by translating chemistry documents from English into French. She was a key laboratory assistant, making their research a true team effort.

The French Revolution and Its Impact

In 1793, during a time called the Reign of Terror in France, Antoine Lavoisier was called a traitor. This was because of his important job with the Ferme Générale. Marie-Anne's father was also arrested for similar reasons. On November 28, 1793, Lavoisier was put in prison.

Marie-Anne visited her husband often while he was in prison. She fought hard to get him released. She told the authorities about his great achievements as a scientist. She explained how important he was to France. But despite her efforts, Lavoisier was found guilty and executed on May 8, 1794. He was 50 years old. Marie-Anne's father was also executed on the same day.

After her husband's death, Marie-Anne was very upset. The new government took all her money and property, though it was later returned. They also took all of Lavoisier's notebooks and lab equipment. Even with these problems, Marie-Anne worked to publish Lavoisier's final writings. These were called Mémoires de Chimie. This book showed his new ideas about chemistry. Her hard work helped keep her husband's important work alive in the field of chemistry.

Later Life and Legacy

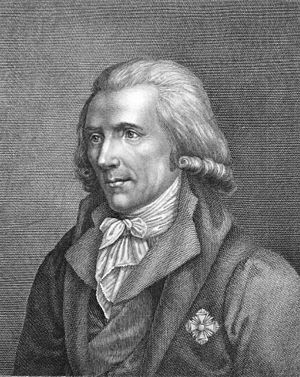

Marie-Anne remarried in 1804 to Benjamin Thompson, a famous physicist. However, their marriage was difficult and did not last long. Marie-Anne always kept her first husband's last name, showing her strong devotion to him. She died suddenly in Paris on February 10, 1836, at 78 years old. She is buried in the Pere-Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Her Contributions to Chemistry

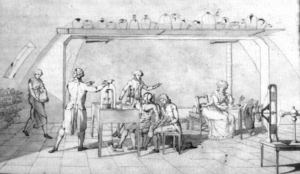

Marie-Anne worked with Lavoisier in his lab every day. She wrote notes in his lab books and drew pictures of his experiments. She had trained with the painter Jacques-Louis David. This training helped her draw the lab equipment very accurately. These drawings helped other scientists understand Lavoisier's methods and results. She also edited his scientific reports.

Together, the Lavoisiers changed the field of chemistry. Before them, chemistry was often confusing. Many believed in the idea of phlogiston. This was a theory that said a fire-like element was gained or lost when things burned.

Marie-Anne was very good at English, Latin, and French. She translated many works about phlogiston into French for her husband. Her most important translation was Richard Kirwan's 'Essay on Phlogiston and the Constitution of Acids'. She not only translated it but also added her own notes. She pointed out mistakes in the chemistry. Her translations were very important for Lavoisier. They helped him stay updated on new ideas in chemistry. It was her translation of the phlogiston theory that helped convince him it was wrong. This led to his studies of burning and his discovery of oxygen gas.

Marie-Anne also played a key role in the 1789 publication of Lavoisier's Elementary Treatise on Chemistry. This book brought together many new ideas in chemistry. It introduced the idea that mass is conserved in chemical reactions. It also listed elements and a new way to name chemicals. Marie-Anne drew thirteen pictures for the book. These showed all the lab tools the Lavoisiers used. She also kept careful records of their experiments. This made their findings more reliable.

Before she died, Marie-Anne managed to get back almost all of Lavoisier's notebooks and lab equipment. Many of these are now kept at Cornell University.

Artistic Skills and Science

Marie-Anne started learning art from the painter Jacques-Louis David around 1785 or 1786. David later painted a famous portrait of Marie-Anne and her husband. Her art training helped her draw and illustrate her husband's experiments. She even drew herself taking part in two of his experiments. She also painted a portrait of Benjamin Franklin, who was one of the many scientists she hosted at her home.

See also

In Spanish: Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze para niños

In Spanish: Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze para niños