Thomas Beddoes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Beddoes

|

|

|---|---|

Thomas Beddoes, pencil drawing by Edward Bird

|

|

| Born | 13 April 1760 Shifnal, England

|

| Died | 24 December 1808 (aged 48) |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Bridgnorth Grammar School |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Oxford, University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Known for | History of Isaac Jenkins |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Maria Edgeworth 1773–1824 |

| Children | Thomas Lovell Beddoes |

Thomas Beddoes (born April 13, 1760 – died December 24, 1808) was an English doctor and science writer. He was born in Shifnal, Shropshire, England. He passed away in Bristol, where he had opened his medical practice 15 years earlier.

Thomas Beddoes was a doctor who wanted to improve medicine and how it was taught. He worked with many important scientists of his time. He was especially interested in finding ways to treat a serious lung disease called tuberculosis.

Beddoes was a friend of the famous poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He also influenced Coleridge's early ideas. Thomas Lovell Beddoes, who also became a poet, was his son. You can see a painting of Thomas Beddoes by Samson Towgood Roch in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Contents

Thomas Beddoes: A Pioneer Doctor

Early Life and Learning

Thomas Beddoes was born on April 13, 1760, at Balcony House in Shifnal, Shropshire. He went to Bridgnorth Grammar School and then to Pembroke College, Oxford. In the early 1780s, he started studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh.

There, he learned chemistry from Joseph Black and natural history from Kendall Walker. He also studied medicine in London with John Sheldon. In 1784, he translated a book about natural history by Lazzaro Spallanzani. The next year, he translated another book by Torbern Olof Bergman about how chemicals attract each other.

He earned his medical doctor degree from Pembroke College, Oxford University, in 1786. In 1794, he married Anna Edgeworth. Her father, Richard Lovell Edgeworth, worked with Beddoes at the Bristol Pneumatic Institution. Their son, the poet Thomas Lovell Beddoes, was born in Bristol in 1803.

A Doctor's Career

After 1786, Beddoes visited Paris and met Lavoisier, a famous chemist. In 1788, Beddoes became a chemistry professor at Oxford University. Many people came to his lectures because they were very interesting.

However, he supported the French Revolution, which caused some people to speak out against him. Because of this, he left his teaching job in 1792.

Beddoes wrote many books and articles from the 1790s to the 1810s. In 1792, he wrote Letter on Early Instruction, Particularly that of the Poor. In this letter, he explained how unfairness could lead to public anger. He believed it was important to educate poor people and improve their living conditions. He also thought it was important to stop violence.

The next year, he published History of Isaac Jenkins. This story showed the dangers of drinking too much alcohol. About 40,000 copies of this book were sold. In 1796, Beddoes wrote An Essay on the Public Merits of Mr. Pitt. This book criticized the policies of Britain's prime minister, William Pitt the Younger. Beddoes felt Pitt's policies ignored the poor and did not use scientific knowledge well.

Beddoes also wanted to improve medical care. He spoke out against people treating themselves with medicines without a doctor's advice. He believed this caused many unnecessary deaths. Through his writings, Beddoes taught the public about healthy living, exercise, and important health issues like tuberculosis.

He also thought that valuable scientific observations were being wasted. He strongly argued for a system to collect and share important medical information with doctors. He suggested creating a national organization for preventing diseases. He saw how many poor people were sick and how many patients came to his pneumatic institution.

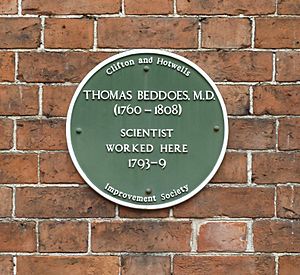

Beddoes focused on treating tuberculosis. He had a clinic in Bristol from 1793 to 1799. Later, he started the Pneumatic Institution to test different gases for treating tuberculosis. This institution later became a general hospital.

Beddoes wrote over 30 books, pamphlets, and articles to push for these changes. He believed it was his job as a doctor to prevent diseases. He thought this could be done by understanding and dealing with the social, material, and physical reasons for illness.

Hope Square Clinic

Between 1793 and 1799, Beddoes had a clinic at Hope Square in Hotwells, Bristol. Here, he treated patients with tuberculosis. He noticed that butchers seemed to get tuberculosis less often than others. So, he kept cows next to his clinic and encouraged patients to breathe near them.

This idea led to some jokes and rumors. People claimed animals were kept in the clinic's bedrooms, which upset the landlords. Even with his belief about cows and tuberculosis, Beddoes was doubtful when Edward Jenner started using a cow-derived vaccination for smallpox a few years later.

Bristol Pneumatic Institution

While living in Hotwells, Beddoes started a project to create a place for treating diseases by having patients breathe in different gases. He called this "pneumatic medicine."

Richard Lovell Edgeworth helped him with this project. In 1799, the Pneumatic Institution opened at Dowry Square, Hotwells. Its first leader was Humphry Davy, who studied the effects of nitrous oxide (laughing gas) in its lab. The original goal of the institution slowly changed. It became a general hospital, and Beddoes left it the year before he died. By 1807, when Beddoes stopped practicing medicine, he estimated his institution had treated over ten thousand patients.

Beddoes was a man of great powers and wide acquirements, which he directed to noble and philanthropic purposes. He strove to effect social good by popularizing medical knowledge, a work for which his vivid imagination and glowing eloquence eminently fitted him.

—Encyclopedia Britannica (1911)

Political Ideas

In its early years, Beddoes strongly supported the French Revolution. He thought a republic was the best way to govern. He had seen how corrupt and divided the British Parliament could be. However, even though he supported democratic protests, Beddoes was afraid of public uprisings and mob violence.

Beddoes was friends with several members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham. This was a group of important thinkers during the Enlightenment. After the Priestley Riots of 1791, Beddoes publicly spoke out against the riots. He showed his support for France and admired French scientists. He also opposed the war against France. In 1792, the Home Office investigated him. They suspected him of "sowing sedition" by giving out political pamphlets that criticized the government. They also looked into his connections to the Lunar Society and possibly Erasmus Darwin's Derby Philosophical Society.

Selected Writings

Besides the works mentioned above, Beddoes was also involved with these writings:

- Chemical Essays by Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1786) – Beddoes translated this work.

- An Account of some Appearances attending the Conversion of cast into malleable Iron. In a Letter from Thomas Beddoes, M. D. to Sir Joseph Banks, Bart. P.R.S. (Phil. Trans. Royal Society, 1791)

- Political Pamphlets (1795–1797) – In this work, Beddoes used the word Biology in its modern sense for the first time.

- Essay on Consumption (1799)

- Essay on Fever (1807)

Beddoes also edited the second edition of John Brown's Elements of Medicine (1795). He also translated some of Johann Karl August Musäus' Volksmärchen der Deutschen into English as Popular Tales of the Germans (1791).

|