Herbert Spencer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Herbert Spencer

|

|

|---|---|

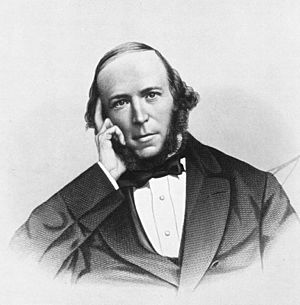

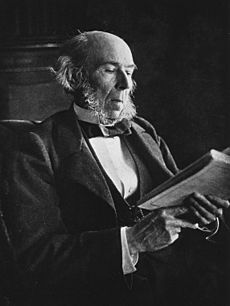

Spencer at the age of 73

|

|

| Born | 27 April 1820 Derby, Derbyshire, England

|

| Died | 8 December 1903 (aged 83) |

|

Notable work

|

Social Statics (1851) The Development Hypothesis (1852) First Principles (1860) The Principles of Psychology The Principles of Biology The Principles of Sociology The Principles of Ethics The Man Versus the State (1884) |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Classical liberalism |

|

Main interests

|

Anthropology · Biology · Evolution · Laissez-faire · Positivism · Psychology · Sociology · Utilitarianism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Social Darwinism Survival of the fittest Social organism Law of equal liberty There is no alternative |

| Signature | |

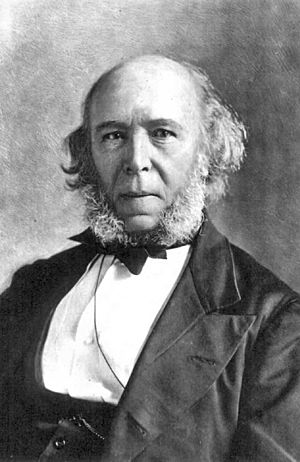

Herbert Spencer (born April 27, 1820 – died December 8, 1903) was an important English thinker. He was a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist.

Spencer came up with the famous phrase "survival of the fittest". He wrote this in his book Principles of Biology in 1864. He got the idea after reading Charles Darwin's book On the Origin of Species. Spencer believed that evolution was a process of development. He thought it applied to the physical world, living things, the human mind, and even human societies and cultures.

By the 1870s and 1880s, Spencer was incredibly popular. His books were translated into many languages, including German, Italian, and Japanese. He received many awards across Europe and North America. He was also a member of special clubs for important thinkers, like the Athenaeum and the X Club. Spencer was one of the few philosophers in history to sell over a million copies of his books during his lifetime.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Herbert Spencer was born in Derby, England, on April 27, 1820. His father, William George Spencer, ran a school that used new teaching methods. His father was also the secretary of the Derby Philosophical Society. This science group was started by Erasmus Darwin, who was Charles Darwin's grandfather.

Spencer was mostly taught at home by his father. His uncle, Reverend Thomas Spencer, helped him learn some math, physics, and a little Latin. This was most of his formal schooling.

Spencer's Writings and Ideas

Spencer published his first book, Social Statics, in 1851. At the time, he was working as an editor for a newspaper called The Economist. In this book, he suggested that people would eventually become perfectly suited to living in society. He also thought that the government would slowly become less important.

His second book, Principles of Psychology, came out in 1855. It didn't sell well at first. Spencer had a big idea: he wanted to show that everything in the universe could be explained by universal laws. This included human culture, language, and even how we decide what is right or wrong. This was different from many religious thinkers who believed some things, like the human soul, were beyond science.

In 1858, Spencer planned a huge project called the System of Synthetic Philosophy. This project aimed to show how the idea of evolution applied to biology, psychology, sociology, and ethics. He thought it would take 20 years to write ten books. It actually took him twice as long and used up most of his life.

Even though he struggled early on, Spencer became the most famous philosopher of his time by the 1870s. His books were widely read. By 1869, he could live off the money from his book sales and articles he wrote for magazines.

Later Years and Legacy

The last years of Spencer's life were often sad and lonely. By the 1890s, fewer people were reading his books. Many of his close friends had passed away. He also started to doubt his strong belief that humanity was always making progress.

He was chosen as a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1883. Spencer kept writing until he became too ill at age 83. He is buried in London's Highgate Cemetery, near Karl Marx's grave. After his funeral, an Indian leader named Shyamji Krishna Varma gave money to start a special teaching position at Oxford University to honor Spencer's work.

Spencer's View on Evolution

Spencer first shared his ideas about evolution in an essay in 1857. This essay later became the basis for his book First Principles of a New System of Philosophy (1862). He argued that everything in the universe starts simple and then becomes more complex and organized. He believed this process of evolution could be seen everywhere.

Spencer also tried to use the idea of biological evolution to understand society. He thought that societies also changed from simpler forms to more advanced ones.

Understanding Society (Sociology)

Spencer's work in sociology looked at how societies grow and become more complex. He described two main types of societies:

- Militant society: This type of society is simple. It is based on strict rules, clear leaders, and people obeying orders.

- Industrial society: This society is more complex. It is based on people choosing to work together and making agreements.

Spencer saw society as a "social organism" that evolves. He believed it moved from a simple state to a more complex one, following the universal laws of evolution.

Ideas on Ethics and Morality

Spencer believed that evolution would eventually lead to a "perfect person in a perfect society." He thought that our minds and morals, passed down through generations, were slowly changing to fit the needs of living in society. For example, aggression might have been useful for survival long ago. But in advanced societies, it would become unnecessary.

He thought that over time, evolution would reduce aggression and increase kindness in people. This would lead to a perfect society where no one would hurt others.

Spencer argued that for people to improve, they needed to experience the natural results of their actions. So, he believed that governments should not try to fix poverty, provide public education, or force vaccinations. He thought that if people faced the consequences of their choices, they would be motivated to improve themselves.

He also felt that too much help given to people who didn't deserve it would break this link between actions and consequences. This link was important for humanity to keep evolving. So, while helping others was good, it had to be balanced. Suffering, he believed, was often the result of someone's own actions.

In a perfect society, people would enjoy helping others (which he called 'positive beneficence'). They would also try not to cause pain to others ('negative beneficence'). People would naturally respect each other's rights. This would lead to everyone following the rule of justice: each person has the right to as much freedom as possible, as long as it doesn't take away the same freedom from others. Spencer called this set of rules 'Absolute Ethics'.

Towards the end of his life, Spencer became less hopeful about the future of humanity.

Views on Religion

Spencer lost his Christian faith when he was a teenager. He later rejected traditional religion. However, he didn't want to attack religion with science. He believed that the human mind can only understand things we can observe. We cannot understand the true reality behind everything. So, he thought both religion and science should accept that human understanding is limited. He called this "awareness of the Unknowable." Spencer believed that worshipping this "Unknowable" could replace traditional religion.

Political Beliefs

Spencer argued that the government was not always needed. He believed that individuals had a "right to ignore the state." He was against countries taking over colonies and expanding their empires. His criticism of the Boer War made him less popular in Britain.

Spencer famously said that "all socialism is slavery." He defined a slave as someone who "works under force to satisfy another's desires." He thought that under socialism or communism, people would be enslaved to the whole community instead of to a single master.

In his later years, Spencer became more traditional in his political views. He had initially supported women's right to vote and the government taking control of land. But by the 1880s, he changed his mind about these ideas.

Influence on Writing

Spencer had a big impact on how people thought about writing. He created a guide for good writing called "The Philosophy of Style." Spencer believed writers should aim to "present ideas so they can be understood with the least possible mental effort" by the reader.

He thought that making the meaning easy to get would make communication most effective. To do this, he suggested putting all the extra information (like descriptive phrases) before the main subject of a sentence. That way, when readers reached the subject, they would already have all the details needed to understand it fully.

Interesting Facts About Herbert Spencer

- Unlike Darwin, Spencer believed that evolution had a specific direction and a final goal: a perfect state of balance.

- Spencer thought there were two kinds of knowledge: what an individual learns, and what humanity learns over time. He believed that intuition, or unconscious knowledge, was inherited from our ancestors.

- Spencer invented an early version of the paper clip. It looked more like a modern cotter pin.

- Spencer never got married.

- In 1902, just before he died, Spencer was nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature. The prize that year went to Theodor Mommsen.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Herbert Spencer para niños

In Spanish: Herbert Spencer para niños

- List of liberal theorists

- Geolibertarianism

- Organicism