Jean-Baptiste Lamarck facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

|

|

|---|---|

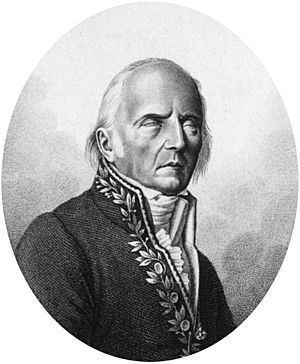

Lamarck by Charles Thévenin, c. 1802

|

|

| Born | 1 August 1744 |

| Died | 18 December 1829 (aged 85) Paris, France

|

| Known for | Evolution; inheritance of acquired characteristics; Philosophie zoologique |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | French Academy of Sciences; Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle; Jardin des Plantes |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Lam. |

| Author abbrev. (zoology) | Lamarck |

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (born August 1, 1744 – died December 18, 1829), known as Lamarck, was a French scientist. He studied nature, biology, and animals. He was also a soldier. Lamarck was one of the first to suggest that living things change over time. This idea is called evolution. He believed these changes happened naturally.

Lamarck fought in a war against Prussia. He was recognized for his bravery. After getting hurt in 1766, he left the army. He then studied medicine. Lamarck became very interested in plants. He wrote a three-volume book about French plants. This book was called Flore françoise (1778). Because of his work, he joined the French Academy of Sciences in 1779.

He worked at the Jardin des Plantes, a famous garden. In 1793, he became a professor of zoology at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. In 1801, Lamarck wrote a big book about animals without backbones. He might have even created the word "invertebrate". In 1802, he was one of the first to use the word "biology" in its modern meaning.

Today, Lamarck is mostly known for his idea about how traits are passed down. This is called the inheritance of acquired characteristics. It is also known as Lamarckism. He wrote about it in his 1809 book Philosophie zoologique. However, this idea was common long before him. It was only a small part of his overall theory of evolution.

Contents

Lamarck's Life Story

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was born in Bazentin, France. He was the 11th child in a family that was once rich but had become poor. Many men in his family served in the French army. When he was a teenager, Lamarck went to a school run by Jesuits.

After his father died in 1760, Lamarck joined the French army. He rode a horse all the way to Germany to join. He was very brave in the Seven Years' War. His company was under heavy fire. Only 14 men were left, with no officers. Lamarck, who was only 17, took command. He refused to retreat until they were told to.

His colonel was very impressed by his courage. Lamarck was promoted to officer right there. But he got an injury to his neck. He was sent to Paris for treatment. He then moved to Monaco. There, he found a book about plants that sparked his interest in nature.

With little money, Lamarck decided to become a doctor. He studied medicine for four years. But he gave it up because his older brother convinced him to. He loved botany, especially after visiting the Jardin des Plantes. He became a student of Bernard de Jussieu, a famous French naturalist. Lamarck spent 10 years studying French plants.

In 1778, he published his book Flore française. This book made him well-known in French science. In 1778, he married Marie Anne Rosalie Delaporte. Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, a top French scientist, helped Lamarck. He helped him join the French Academy of Sciences in 1779. He also helped him become a royal botanist in 1781. This job allowed him to travel to other countries.

Lamarck collected rare plants and other natural items. These were not found in French gardens or museums. In 1788, he became the keeper of the herbarium at the Royal Garden. This was a collection of dried plants.

During the French Revolution in 1790, Lamarck changed the garden's name. He changed it from Jardin du Roi (King's Garden) to Jardin des Plantes. This name did not connect it so closely to King Louis XVI. In 1793, he became a professor of invertebrate zoology. He earned a good salary. Lamarck married two more times after his first wife died.

For six years as a professor, Lamarck published only one paper. It was about the moon's effect on Earth's atmosphere. At first, Lamarck believed that species never changed. But after studying molluscs, he became convinced that species did change over time. He started to develop his ideas about evolution. He first shared these ideas in a lecture in 1800.

In 1801, he published Système des Animaux sans Vertèbres. This was a big book about classifying invertebrates. He created new groups for animals like echinoderms, arachnids, crustaceans, and annelids. He was the first to separate spiders from insects. He also made crustaceans a separate group from insects.

In 1802, Lamarck published Hydrogéologie. In this book, he used the term "biology" in its modern way. He also wrote about geology. He believed that continents slowly moved westward.

That same year, he published Recherches sur l'Organisation des Corps Vivants. In this book, he explained his theory of evolution. He thought all life was arranged in a chain. Simple life forms were at the bottom, and complex forms were at the top. This showed a path of progress in nature.

Lamarck disagreed with the new chemistry ideas of Lavoisier. He also had conflicts with Georges Cuvier, a respected scientist who did not believe in evolution. Cuvier often made fun of Lamarck's ideas.

Lamarck slowly became blind. He died in Paris on December 18, 1829. His family was very poor. His body was buried in a common grave. Later, his body was dug up and lost.

Lamarck's Ideas on Evolution

Lamarck's ideas about evolution came from his work on geology. He thought that the same principles that cause erosion could apply to living things. He believed that organs could become more complex and pass these changes to their offspring. This was a big change from his earlier belief that species did not change.

Lamarck focused on two main ideas in his work on biology:

- The environment causes changes in animals. For example, moles are blind because they live underground. Birds do not have teeth because they do not need them.

- Life is organized in a structured way. Different body parts work together for animals to move and live.

Lamarck was not the first to talk about evolution. But he was the first to create a complete theory of how it works. He explained his ideas in several books:

- Recherches sur l'organisation des corps vivants, 1802.

- Philosophie zoologique, 1809.

- Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres, (seven volumes, 1815–22).

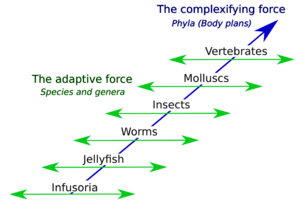

Lamarck used ideas from his time to explain evolution. He thought there were two main forces. One force made animals more complex. The other force helped animals adapt to their local environments. He believed these forces were natural results of basic physical rules.

The Force of Life: Becoming More Complex

Lamarck believed that living things naturally tend to become more complex. He called this Le pouvoir de la vie (The power of life). He thought that simple living things were always being created naturally. Then, over time, these simple organisms would change and become more complex.

He believed that organisms moved from simple to complex in a steady way. This was based on old ideas about how elements work. In this view, simple organisms never disappeared. This is because new ones were always being created. Lamarck thought that this process was ongoing. Simple organisms would keep changing and becoming more complex.

Adapting to Surroundings: The Adaptive Force

The second part of Lamarck's theory was about how organisms adapt to their environment. This force could make organisms move up the ladder of progress. It could also lead to new and different forms with local adaptations. Lamarck believed this adaptive force came from how organisms interacted with their environment. It was also powered by how much they used or didn't use certain body parts.

First Law: Use and Disuse

Lamarck's First Law states: If an animal uses an organ more often, that organ becomes stronger and bigger. The more it is used, the more powerful it becomes. But if an organ is not used, it slowly becomes weaker and smaller. It loses its ability to work, and eventually, it might disappear.

Second Law: Passing on Acquired Traits

Lamarck's Second Law states: Any changes an animal gains or loses during its life are passed on to its offspring. This happens if the changes are caused by the environment. It also happens if they are due to using or not using an organ. These changes are passed on, as long as both parents have them, or at least the parents that have babies.

This idea is called soft inheritance or the inheritance of acquired characteristics. It is often simply called "Lamarckism." Today, scientists are studying epigenetics. This field looks at how traits can be passed down without changing the DNA. For example, changes in behavior or environment can affect how genes work. These changes can sometimes be passed on to the next generation. This has made some scientists wonder if Lamarck's ideas were partly right, in a new way.

Lamarck's Beliefs About God

In his book Philosophie zoologique, Lamarck called God the "great author of nature." Historians believe Lamarck was a deist. This means he believed God created the world and its laws. But he thought God did not interfere with it after creation.

One historian, Jacques Roger, wrote that Lamarck was a materialist. This means he believed everything in nature, even the highest forms of life, came from natural processes. He did not think a spiritual force was needed.

Lamarck's Impact

Lamarck is mostly known for his ideas on evolution. His theories became more famous after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859. Some people who disagreed with Darwin's new theory looked back to Lamarck's ideas as an alternative.

Lamarck is remembered for his belief in the inheritance of acquired characteristics. This is the idea that traits gained during life can be passed on. He also believed in the "use and disuse" model. This model says that organs develop or shrink based on how much they are used.

Lamarck created one of the first complete theories of how living things change over time. Even though his theory was not widely accepted during his life, some scientists today see his importance. Stephen Jay Gould called Lamarck the "primary evolutionary theorist." He meant that Lamarck's ideas helped shape how people thought about evolution for a long time.

New discoveries in epigenetics have led to new discussions. Epigenetics studies how traits can be passed down without changing the DNA sequence. This has made some scientists wonder if a "neolamarckist" view of inheritance could be partly true.

Darwin himself believed that use and disuse could play a small role in evolution. He praised Lamarck for making people think about how all changes in the living world happen through natural laws, not miracles.

Animals and Plants Named by Lamarck

Lamarck named many species during his life. Many of these names are still used today. For example, he named families of animals like ark clams (Arcidae), sea hares (Aplysiidae), and cockles (Cardiidae). He also named some plant groups, like the mosquito fern (Azolla).

Animals and Plants Named After Lamarck

Many species have been named in honor of Lamarck. These include the honeybee subspecies Apis mellifera lamarckii and the bluefire jellyfish (Cyaneia lamarckii). Several plants are also named after him, such as Amelanchier lamarckii (juneberry) and the grass group Lamarckia.

More than 100 marine species or groups have names like "lamarcki" or "lamarckii". Some of these include:

- Acropora lamarcki (a coral)

- Bursa lamarckii (a frog snail)

- Carinaria lamarckii (a small sea snail)

- Cyanea lamarckii (a jellyfish)

- Genicanthus lamarck (a saltwater angelfish)

- Morum lamarckii (a small sea snail)

- Spondylus lamarckii (a thorny oyster)

Lamarck's Main Books

- 1778. Flore françoise, ou, Description succincte de toutes les plantes qui croissent naturellement en France (French Flora, or, Brief Description of All Plants Growing Naturally in France)

- 1809. Philosophie zoologique, ou Exposition des considérations relatives à l'histoire naturelle des animaux... (Zoological Philosophy, or, Exposition of Considerations Related to the Natural History of Animals...)

- 1815–22. Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres, présentant les caractères généraux et particuliers de ces animaux... (Natural History of Animals Without Backbones, Presenting the General and Particular Characteristics of These Animals...)

See also

In Spanish: Jean-Baptiste Lamarck para niños

In Spanish: Jean-Baptiste Lamarck para niños

- Evolution

- Epigenetics

- Natural selection

- Mount Lamarck

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |