Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Comte de Buffon

|

|

|---|---|

Painting by François-Hubert Drouais

|

|

| Born |

Georges-Louis Leclerc

7 September 1707 |

| Died | 16 April 1788 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Histoire Naturelle Buffon's needle problem Rejection sampling |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural history |

| Institutions | Jardin du Roi |

| Influences | Nicolas Antoine Boulanger |

| Influenced | Nicolas Desmarest Jean-Baptiste Lamarck Stanisław Staszic |

| Signature | |

|

|

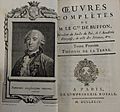

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (French: [ʒɔʁʒ lwi ləklɛʁ kɔ̃t də byfɔ̃]; born September 7, 1707 – died April 16, 1788) was an important French scientist. He was a naturalist (someone who studies nature), a mathematician, and a cosmologist (someone who studies the universe).

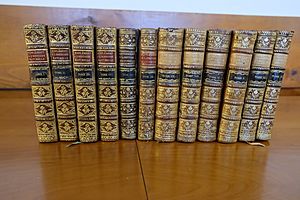

His ideas greatly influenced scientists who came after him. Two famous French scientists, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Georges Cuvier, were inspired by his work. Buffon wrote a huge, multi-volume book called Histoire Naturelle (Natural History). He published 36 volumes during his lifetime. More volumes were published after he died, using his notes.

A famous biologist, Ernst Mayr, said that Buffon was "the father of all thought in natural history" in the late 1700s. Buffon was one of the first to notice how nature changes over time, a process called ecological succession. However, some of his ideas about Earth's history and how animals changed were not accepted at the time. The University of Paris made him take back some of his theories because they went against the Bible's story of Creation.

Buffon was also the director of the Jardin du Roi, which is now a famous garden and museum in Paris called the Jardin des Plantes.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Georges Louis Leclerc was born in Montbard, a region in France called Burgundy. His father, Benjamin Francois Leclerc, worked for the local government. His mother, Anne-Christine Marlin, also came from a family of civil servants. When Georges was seven, his godfather, Georges Blaisot, died and left him a lot of money.

With this money, Georges's father bought an estate that included the village of Buffon. The family moved to Dijon, where his father took on more important jobs.

Georges went to a Jesuit school in Dijon when he was ten. From 1723 to 1726, he studied law in Dijon. This was a common path for people in his family. In 1728, Georges went to the University of Angers to study mathematics and medicine. While there, he met the young Duke of Kingston from England. Buffon traveled with the Duke's group for about a year and a half through southern France and parts of Italy.

In 1732, after his mother passed away, Georges returned to Dijon. He wanted to make sure he received his inheritance. During his travels, he had added "de Buffon" to his name. He then bought back the village of Buffon, which his father had sold. With a large fortune, Buffon moved to Paris to study science. He focused on mathematics and mechanics, and also worked to increase his wealth.

Career as a Scientist

In 1732, Buffon moved to Paris. There, he met famous thinkers like Voltaire. He first became known for his work in mathematics. He used advanced math, called calculus, to study probability theory. The famous problem of Buffon's needle in probability is named after him. In 1734, he became a member of the French Academy of Sciences.

A powerful person named Maurepas asked the Academy of Sciences to study wood for building ships. Buffon started a long study, testing the strength of wood. He found that small pieces of wood didn't always show how strong a large piece would be. So, he began testing full-size wooden beams.

In 1739, with Maurepas's help, Buffon became the head of the Jardin du Roi in Paris. He kept this job for the rest of his life. Buffon helped turn the Jardin du Roi into a major science center and museum. He made it bigger by buying more land. He also brought in new plants and animals from all over the world.

Buffon was also a talented writer. In 1753, he was invited to join the Académie Française, another important French academy. He was also elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1768. In one of his famous speeches, he said, "Le style c'est l'homme même", which means "The style is the man himself."

In 1752, Buffon married Marie-Françoise de Saint-Belin-Malain. She was from a noble family in Burgundy. His wife passed away in 1769. In 1772, Buffon became very ill. The King then made Buffon's lands in Burgundy into a county. This meant Buffon (and his son) became a count. He died in Paris in 1788.

During the French Revolution, his tomb was broken into. His heart was saved for a while but later lost. Today, only a part of his brain, his cerebellum, remains. It is kept in the base of a statue made in his honor at the Museum of Natural History in Paris.

Major Works and Ideas

Buffon's most famous work was his Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière (Natural History, General and Particular). It was published from 1749 to 1788. This huge work was meant to cover all of nature. But it ended up focusing on animals and minerals, especially birds and four-legged animals (quadrupeds). This book was written in a beautiful style and was read by almost everyone educated in Europe. Many people helped him with this big project, including Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton and many artists. Buffon's Histoire naturelle was translated into many languages. This made him one of the most widely read authors of his time.

In the first parts of Histoire naturelle, Buffon questioned how useful mathematics was. He also criticized Carl Linnaeus's way of classifying plants and animals. Buffon also wrote about the history of Earth in a way that was different from the Bible. He also suggested a theory of how living things reproduce that was new for his time. Because of these ideas, the Faculty of Theology at the Sorbonne (a famous university in Paris) criticized his early volumes. Buffon officially took back his statements, but he kept publishing the same ideas without changes.

While studying animals, Buffon noticed something important. Even if two places had similar environments, they often had different plants and animals. This idea is now known as Buffon's Law. It is considered the first rule of biogeography, which is the study of where living things are found on Earth. He also thought that species might have "improved" or "degenerated" after spreading from a central point. In one volume, he suggested that all the world's quadrupeds came from just 38 original types of quadrupeds. Because of this, some people see him as an early thinker about evolution, before Charles Darwin. He also believed that climate change might have helped species spread around the world.

Buffon looked at the similarities between humans and apes. However, he did not believe that humans and apes shared a common descent (meaning they came from the same ancestor).

At one point, Buffon had a theory that nature in the New World (the Americas) was not as good as nature in Eurasia. He said that the Americas lacked large, powerful creatures. He even thought that people there were less strong than Europeans. He blamed this on the marshy smells and thick forests of the American continent. These comments made Thomas Jefferson (who later became a U.S. president) very angry. Jefferson even sent soldiers to find a large moose in New Hampshire to prove to Buffon how grand American animals were.

In his book Les époques de la nature (The Epochs of Nature) from 1778, Buffon wrote about how the Solar System might have formed. He guessed that the planets were created when a comet crashed into the Sun. He also suggested that the Earth was much older than 4004 BC. This date was what Archbishop James Ussher had calculated based on the Bible. Buffon used tests on how fast iron cooled down in his lab. He calculated that the Earth was 75,000 years old. Again, the Sorbonne criticized his ideas. And again, he took back his statements to avoid more trouble.

Racial Studies

Buffon, along with Johann Blumenbach, believed in monogenism. This is the idea that all human races came from a single origin. They also thought that different races appeared due to "degeneration" from environmental factors. For example, they believed that Adam and Eve were Caucasian. They thought other races developed because of things like the tropical sun or poor diet. They believed that these changes could be reversed if people lived in the right environment. They thought all human groups could eventually return to the original Caucasian form.

Buffon and Blumenbach suggested that skin color changed because of the heat from the sun. They thought cold winds caused the brownish color of the Eskimos. They believed the Chinese had lighter skin than other Asian groups because they mostly lived in towns and were protected from the environment. Buffon said that food and lifestyle could make races "degenerate" and become different from the first Caucasian race.

Because he believed in monogenism, Buffon thought that a person's skin color could change during their lifetime. This would depend on the climate and their diet.

Buffon also supported the idea that humans first appeared in Asia. In his Histoire Naturelle, he argued that the first humans must have lived in a warm, mild climate zone. He thought good climate conditions would lead to healthy humans. So, he guessed that the most likely place to find the first humans was in Asia, near the Caspian Sea.

Influence on Modern Biology

Charles Darwin, famous for his theory of evolution, mentioned Buffon in his book On the Origin of Species. Darwin first said he wasn't familiar with Buffon's writings. Later, he changed it to say that Buffon was "the first author who in modern times has treated it [evolution] in a scientific spirit." However, Darwin noted that Buffon's ideas changed often. Also, Buffon didn't explain how species changed.

Buffon wrote about the idea of a struggle for existence, where living things compete to survive. He also developed a system of heredity (how traits are passed down) that was similar to Darwin's idea of pangenesis. Darwin even said that if Buffon had thought his "organic molecules" came from every part of the body, their ideas would have been very similar.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon para niños

In Spanish: Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon para niños

- Scientific Revolution

- Suites à Buffon

- Buffon's Needle

- Rejection sampling