James Ussher facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Most Reverend James Ussher |

|

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Armagh Primate of All Ireland |

|

|

|

| Church | Church of Ireland |

| See | Armagh |

| Appointed | 21 March 1625 |

| In Office | 1625–1656 |

| Predecessor | Christopher Hampton |

| Successor | John Bramhall (from 1661) |

| Other posts | Professor, Trinity College Dublin Chancellor, St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin Prebend of Finglas. |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1602 |

| Consecration | 2 December 1621 by Christopher Hampton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 January 1581 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 21 March 1656 (aged 75) Reigate, Surrey, England |

| Buried | Chapel of St Erasmus, Westminster Abbey |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Previous post | Bishop of Meath (1621–1625) |

| Alma mater | Trinity College Dublin |

| Coat of arms | |

James Ussher (born January 4, 1581 – died March 21, 1656) was an important Irish church leader. He served as the Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland for the Church of Ireland from 1625 to 1656.

Ussher was a brilliant scholar and a key figure in the church. He is well-known for two main things:

- He correctly identified the true letters written by an early church leader named Ignatius of Antioch.

- He created a famous timeline that calculated the date of the Creation of the world. He believed it happened around 6 PM on October 22, 4004 BC.

Contents

Early Life and Education

James Ussher was born in Dublin, Ireland, into a wealthy family. His grandfather, James Stanihurst, was a speaker in the Irish parliament. His mother, Margaret, was reportedly a Roman Catholic.

Ussher had a younger brother, Ambrose Ussher, who became a skilled scholar of Arabic and Hebrew. James Ussher was taught to read by his two blind aunts. He was very good at languages, learning many of them.

He started at Trinity College Dublin on January 9, 1594, when he was just 13 years old. This was a normal age for students back then. He earned his first degree by 1598 and became a fellow and earned his master's degree by 1600.

In May 1602, he became a deacon in the Church of Ireland, which was the official church. His uncle, Henry Ussher, who was also an Archbishop of Armagh, ordained him.

Becoming a Church Leader

Ussher continued to rise in the church and academic world:

- In 1605, he became the Chancellor of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.

- He became a professor of theology at Trinity College in 1607.

- He earned his Doctor of Divinity degree in 1612.

- He was made Vice-Chancellor in 1615.

In 1613, he married Phoebe Challoner. In 1615, he helped create the first official beliefs of the Church of Ireland.

Career as Archbishop

In 1619, Ussher traveled to England and stayed for two years. He met King James I and became well-known. In 1621, King James I appointed Ussher as the Bishop of Meath.

He became an important figure in Ireland and a respected scholar. He collected many old Irish writings and shared them with other researchers. From 1623 to 1626, he was in England again, studying church history.

In 1625, he was chosen to be the Primate of All Ireland and Archbishop of Armagh. He took over from Christopher Hampton.

Challenges as Primate

After becoming Archbishop in 1626, Ussher faced a lot of political unrest. There was tension between England and Spain. King Charles I offered Irish Catholics some religious freedoms, called "The Graces," in exchange for money to support the army.

Ussher was a strong Calvinist and was worried about Catholics gaining power. In November 1626, he held a secret meeting with Irish bishops. They wrote a statement called the "Judgement of the Arch-Bishops and Bishops of Ireland." It said:

The religion of the papists is superstitious and idolatrous; their faith and doctrine erroneous and heretical; their church in respect of both, apostatical; to give them, therefore, a toleration, or to consent that they may freely exercise their religion, and profess their faith and doctrine, is a grievous sin.

This statement was read publicly in Dublin in April 1627. The proposed laws for "The Graces" were not fully put into action before a rebellion started in 1641.

Church Reforms and Conflicts

From 1629, there were more efforts to make everyone in Ireland follow the same religious rules. In 1633, Ussher wrote to William Laud, the new Archbishop of Canterbury, asking for support to fine Irish Catholics who did not attend Protestant services.

Thomas Wentworth, the new Lord Deputy in Ireland, arrived in 1633. He focused on making the Church of Ireland stronger first. He also settled a long-standing argument about which church, Armagh or Dublin, had more authority, deciding in favor of Armagh.

Ussher and Wentworth also disagreed about theatre. Ussher, like many Puritans, disliked plays. Wentworth, however, loved theatre and helped start Ireland's first theatre, the Werburgh Street Theatre, despite Ussher's objections.

Ussher also found himself disagreeing with the rise of Arminianism, a different theological view. Wentworth and Laud wanted the Church of Ireland to be more like the Church of England. At a church meeting in 1634, Ussher made sure that the English Articles of Religion were added to the Irish ones, not replacing them. He also ensured Irish church laws were updated, not simply replaced.

By 1635, Ussher had less control over the church's daily matters. This power shifted to John Bramhall, Bishop of Derry, and to Archbishop Laud for overall policy.

Despite these challenges, Ussher was seen as an effective and important leader. He preferred to focus on his studies when he could. He often debated with Catholic theologians. He also wrote a lot about theology and church history.

In 1631, he published "Discourse on the Religion Anciently Professed by the Irish." This important work showed how the early Irish church was different from Rome and closer to the later Protestant church. This idea helped establish the Church of Ireland as the true continuation of the early Celtic church.

In 1639, he published Britannicarum ecclesiarum antiquitates (Antiquities of the British Churches). This book was a huge achievement because it brought together many old writings that had never been published before.

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

In 1640, Ussher left Ireland for England, which turned out to be his last time there. Before the Wars of the Three Kingdoms began, both the King and Parliament respected Ussher's knowledge and his moderate views.

After the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Ussher lost his home and income. Parliament gave him a pension, and the King gave him the income from the vacant See of Carlisle.

Ussher remained a loyal friend to Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford. When Parliament sentenced Wentworth to death, Ussher begged the King not to allow the execution. He believed the King had promised to spare Wentworth's life. The King did not follow his advice, but later regretted it.

In 1641, Ussher suggested a way to bridge the gap between those who supported bishops (like Laud) and those who wanted to get rid of them (Presbyterians). His idea, called "The Reduction of Episcopacy," suggested that bishops could work within a Presbyterian system. The King rejected this idea, but it was published after Ussher's death in 1656 and was influential for many years.

As the conflict between the King and Parliament grew, Ussher had to choose sides. He reluctantly chose to support the King. In January 1642, he moved to Oxford, a place loyal to the King. Even when King Charles negotiated with Catholic Irish, Ussher remained loyal. He moved to different places as the King's side lost power.

In June 1646, he returned to London under the protection of his friend, Elizabeth, Dowager Countess of Peterborough. He stayed in her homes from then on. Parliament removed him from his position as Bishop of Carlisle in October 1646, as bishops were abolished during the Commonwealth period.

He became a preacher in London in 1647. Despite his loyalty to the King, his friends in Parliament protected him. He watched the execution of Charles I from a rooftop but fainted before the execution happened.

Studying Ignatius's Letters

Ussher wrote two important studies about the letters of Ignatius of Antioch. These were great scholarly achievements that most modern experts agree with.

In Ussher's time, the most common collection of Ignatius's writings was a set of 16 letters called the "Long Recension." Ussher carefully studied them and found problems that no one had noticed for centuries. He saw differences in how they were written, their ideas, and references to things that didn't exist in Ignatius's time.

Ussher researched and found a shorter set of letters, called the "Middle Recension." He argued that only the letters in this shorter set were truly written by Ignatius. He believed that someone else had edited Ignatius's work and added their own ideas to the "Long Recension." He published his Latin edition of the genuine Ignatian works in 1644.

The only main difference between Ussher's view and what scholars believe today is that Ussher thought the Epistle of Ignatius to Polycarp was not real. Most modern scholars now believe it is genuine.

Ussher's Famous Chronology

After his church duties lessened, Ussher focused on his research and writing. He returned to studying timelines and early church leaders. After a book on the origin of Christian beliefs in 1647, he published a work on calendars in 1648.

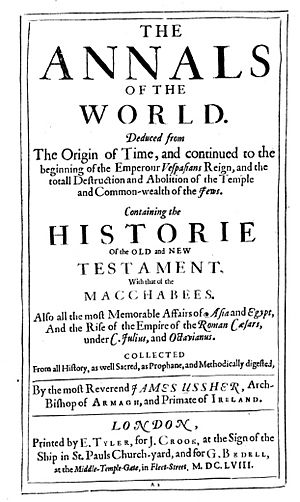

This led to his most famous work, Annales veteris testamenti, a prima mundi origine deducti (Annals of the Old Testament, deduced from the first origins of the world), published in 1650. Its continuation came out in 1654.

In this work, Ussher calculated that the Creation of the world happened at nightfall on October 22, 4004 BC. Other scholars also calculated dates for Creation, like John Lightfoot from Cambridge. Ussher's exact time is often misquoted, but he specified it as around 6 PM on October 22.

Today, Ussher's work is used to support Young Earth Creationism, which believes the universe was created thousands of years ago. While calculating the date of Creation is a debated topic now, in Ussher's time, it was considered an important task. Many scholars, including Joseph Justus Scaliger and Isaac Newton, had tried to do it.

Ussher's chronology was a huge scholarly achievement. It required deep knowledge of ancient history, including the rise of the Persians, Greeks, and Romans. He also needed to be an expert in the Bible, biblical languages, astronomy, and ancient calendars.

His timeline of historical events, when he used sources other than the Bible, usually matches modern accounts. For example, he placed the death of Alexander in 323 BC and Julius Caesar's death in 44 BC.

To calculate the Creation date, Ussher used the Masoretic version of the Torah, which claims a very accurate history of copying. He chose this version because it placed Creation exactly 4,000 years before 4 BC, which was the generally accepted date for the birth of Jesus. He also calculated that Solomon's Temple was finished 3,000 years after Creation. This meant there were exactly 1,000 years from the Temple to Jesus.

Death and Legacy

In 1655, Ussher published his last book, De Graeca Septuaginta Interpretum Versione. This was the first serious study of the Septuagint, an ancient Greek translation of the Old Testament. He discussed how accurate it was compared to the Hebrew text.

In 1656, he was staying at the Countess of Peterborough's house in Reigate, Surrey. On March 19, he felt a sharp pain and went to bed. He likely suffered a severe internal bleeding. Two days later, he died at the age of 75. His last reported words were: "O Lord, forgive me, especially my sins of omission."

His body was prepared for burial in Reigate. However, Oliver Cromwell insisted that Ussher be given a state funeral. On April 17, he was buried in the Chapel of St Erasmus in Westminster Abbey.

Works

- – The Life of James Ussher, D.D.

- – incl. De Christianorum Ecclesiarum Successione et Statu historica Explicatio (1613)

- – An Answer to a Challenge made by a Jesuit in Ireland

- – incl. Gotteschalci et Praedestinatione Controversiae abeomotae Historia (1631); Veterum Epistolarum Hibernicarum Sylloge (1632)

- – Brittanicarum Ecclesiarum Antiquitates; caput I–XIII (1639)

- – Brittanicarum Ecclesiarum Antiquitates; caput XIV–XVII (1639)

- – A Geographical and Historical Disquisition, touching the Asia properly so called; The Original of Bishops and Metropolitans briefly laid down; The Judgment of Doctor Rainoldes, touching the Original of Episcopacy, more largely confirmed out of Antiquity; Dissertatio non-de Ignati solum et Polycarpi scriptis, sed etiam de Apostolicis Constitutionibus et Canonibus Clementi Romano attributis (1644); Praefationes in Ignatium (1644); De Romanae Ecclesiae Symbolo vetere aliisque Fidei Formulis tum ab Occidentalibus tum ab Orientalibus in prima Catechesi et Baptismo proponi solitis (1647); De Macedonum et Asianorum Anno Solari Dissertatio (1648); De Graeca Septuaginta Interpretum Versione Syntagma, cum Libri Estherae editione Origenica et vetere Graeca altera; Epistola ad Ludovicum Capellum de variantibus Textus Hebraei Lectionibus; Epistola Gulielmi Eyre ad Usserium

- – Annales veteris Testamenti, a Prima Mundi Origine deducti, una cum Rerum Asiaticarum Aegypticarum Chronico, a temporis historici principio usque ad Maccabaicorum initia producto (1650)

- – Annales veteris Testamenti (contd.)

- – Annales veteris Testamenti (contd.)

- – Annales veteris Testamenti concludes; Annalium Pars Posterior, in qua, praeter Maccabaicam et novi testamenti historiam, Imperii Romanorum Caesarum sub Caio Julio et Octaviano Ortus, rerumque in Asia et Aegypto Gestarum continetur Chronicon ... (1654)

- – Chronologia sacra (1660); Historia Dogmatica Controversiae inter Orthodoxos et Pontificios de Scripturis et Sacris Vernaculis; Dissertatio de Pseudo-Dionysii scriptis; Dissertatio de epistola ad Laodicenses

- – sermons (in English)

- – Tractatus de Controversiis Pontificiis; Praelectiones Theologicae

- – letters (in English) (incl. first to Richard Stanihurst, his uncle)

- – letters (in English and Latin)

- – indexes

See also

In Spanish: James Ussher para niños

In Spanish: James Ussher para niños