Stephen Jay Gould facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Stephen Jay Gould

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | September 10, 1941 |

| Died | May 20, 2002 (aged 60) Manhattan, New York, U.S.

|

| Education | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Paleontology, evolutionary biology, history of science |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Pleistocene and Recent History of the Subgenus Poecilozonites (Poecilozonites) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata) in Bermuda: An Evolutionary Microcosm (1967) |

| Doctoral advisors |

|

| Doctoral students |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Stephen Jay Gould (born September 10, 1941 – died May 20, 2002) was an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and science historian. He was one of the most important and popular science writers of his time. Gould spent most of his career teaching at Harvard University and working at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. He also taught at New York University later in his life.

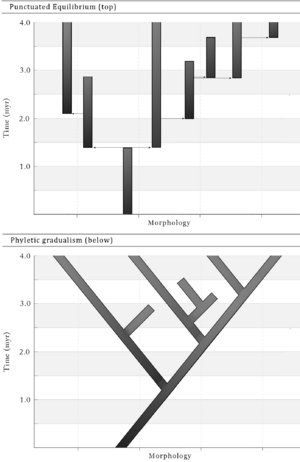

Gould's biggest idea in evolutionary biology was the theory of punctuated equilibrium. He developed this idea with Niles Eldredge in 1972. This theory suggests that evolution often happens in long periods of little change, broken up by short bursts of rapid change and new species forming. This was different from the older idea that evolution always happens slowly and steadily.

Gould studied land snails for much of his research. He also made important contributions to evolutionary developmental biology, which looks at how changes in development can lead to evolution. He believed that not all features of living things are direct adaptations. He also argued against applying strict biological rules to all human behavior. Gould was a strong opponent of creationism and believed that science and religion should be seen as two separate areas that do not conflict.

Many people knew Gould from his 300 popular essays in Natural History magazine. He also wrote many books for both scientists and the general public. In 2000, the US Library of Congress called him a "Living Legend".

Contents

Stephen Gould's Life Story

Stephen Jay Gould was born in Queens, New York, on September 10, 1941. His father, Leonard, was a court reporter and a World War II veteran. His mother, Eleanor, was an artist. Stephen and his younger brother, Peter, grew up in Bayside, a middle-class neighborhood.

When Gould was five years old, his father took him to the Hall of Dinosaurs at the American Museum of Natural History. There, he saw a Tyrannosaurus rex. Gould later said, "I had no idea there were such things—I was awestruck." It was at that moment that he decided to become a paleontologist.

Gould was raised in a non-religious Jewish home. He did not formally practice religion and preferred to be called an agnostic. He believed in fairness and equality for all people.

While attending Antioch College in the early 1960s, Gould was active in the civil rights movement. He often worked for social justice. He even organized protests in England against a dance hall that would not let black people in. Throughout his life, he spoke out against unfairness and false science used to support racism or sexism.

Gould had many interests outside of science. As a boy, he collected baseball cards and was a big New York Yankees fan. As an adult, he liked science fiction movies, but often wished they had better stories and science. He also enjoyed singing and was a fan of Gilbert and Sullivan operas. He collected rare books and loved architecture and walking around cities. He traveled to Europe often and spoke French, German, Russian, and Italian.

Family Life

Gould married artist Deborah Lee on October 3, 1965. They met in college and had two sons, Jesse and Ethan. They were married for 30 years. In 1995, he married artist and sculptor Rhonda Roland Shearer.

Health Challenges

In 1982, Gould was diagnosed with a serious type of cancer that affected his abdomen. After a difficult two years, he recovered. He wrote an essay called "The Median Isn't the Message." In it, he explained that statistics, like the average survival time for a disease, don't tell the whole story for every person. He found comfort in understanding that individual experiences can be very different from averages.

In 2002, Gould was diagnosed with a different, aggressive cancer in his lung that had spread. He passed away 10 weeks later, on May 20, 2002, at his home in New York.

Stephen Gould's Scientific Work

Gould started his higher education at Antioch College, studying geology and philosophy. He then earned his PhD from Columbia University in 1967. After that, he began teaching at Harvard University, where he worked for the rest of his life. At Harvard, he became a professor of geology and a curator of invertebrate paleontology (the study of fossils without backbones).

He received many honors for his work. In 1983, he was given a fellowship by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He also served as president of the Paleontological Society and the Society for the Study of Evolution. In 1989, he was elected to the United States National Academy of Sciences. In 2008, after his death, he was awarded the Darwin–Wallace Medal.

Punctuated Equilibrium: Evolution in Bursts

Early in his career, Gould and his friend Niles Eldredge developed the theory of punctuated equilibrium. This idea says that new species appear relatively quickly in the fossil record. These rapid changes are followed by long periods where species don't change much. Gould came up with the name "punctuated equilibria."

This theory changed how many scientists thought about evolution. Some thought it was a big new idea, while others saw it as a small change to existing ideas. It showed that evolution doesn't always happen slowly and steadily, as many people had believed.

How Organisms Develop and Evolve

Gould made important contributions to evolutionary developmental biology. This field looks at how changes in an organism's development can lead to evolutionary changes. In his book Ontogeny and Phylogeny, he talked about processes like heterochrony. This is when the timing or speed of development changes, leading to new features in a species.

Beyond Natural Selection: Spandrels

With his colleague Richard Lewontin, Gould wrote an important paper in 1979 called "The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm." They used the architectural term "spandrel" to explain a concept in biology. In architecture, a spandrel is a triangular space that appears when you put a round arch under a dome. It's not something the architect planned directly, but a necessary result of the design.

Gould and Lewontin used this idea to suggest that not all features of an organism are directly chosen by natural selection because they are useful. Some features, they argued, might just be side effects of other features that were selected. For example, the human brain is very complex, and some of its higher functions might be "spandrels"—unintended side effects of its overall growth, not directly selected for. This idea is still debated by scientists today.

Evolutionary Progress: Not a Ladder

Gould argued that evolution does not have a built-in goal to make things "better" or more complex. Many people imagine evolution as a ladder, leading to bigger, faster, and smarter organisms, with humans at the top. Gould believed that evolution's main drive was towards diversification (creating more different kinds of life).

He pointed out that life started simple (like bacteria). Any new diversity from that simple start would naturally spread out, making some things more complex. But life can also become simpler, like many parasites do. So, evolution is not always about getting more complex.

Studying Land Snails

Much of Gould's hands-on research focused on land snails. He studied the Poecilozonites snails from Bermuda and later the Cerion snails from the Caribbean. He was fascinated by the huge variety of shapes in Cerion snails, even though they were all part of the same group and could interbreed. He wanted to understand how such different forms could evolve with seemingly small genetic differences.

Stephen Gould as a Public Figure

Gould became very well known through his popular essays about evolution in Natural History magazine. He wrote 300 essays from 1974 to 2001. Many of these essays were collected into bestselling books like Ever Since Darwin and The Panda's Thumb.

He was a passionate supporter of evolutionary theory and worked hard to explain complex ideas to a wide audience. He also loved baseball and often wrote about it, using baseball examples to explain scientific concepts.

Gould was a strong opponent of creationism, which is the belief that life was created by a divine being, often based on religious texts. He testified in court against laws that tried to teach creationism in science classes. He also developed the idea of "non-overlapping magisteria" (NOMA). This idea suggests that science and religion deal with different areas of human understanding and should not try to tell each other what to do. Science deals with facts about the universe, while religion deals with questions of meaning and values.

Gould often appeared on television shows like NOVA and Charlie Rose. He was also featured in documentaries like Ken Burns's Baseball. In 1997, he even voiced a cartoon version of himself on The Simpsons TV show. The show paid tribute to him after his death in 2002.

Debates and Discussions

Stephen Gould received many awards for his scientific work and popular writings. However, some biologists felt that his public ideas were different from what most evolutionary scientists believed. These debates became known as "The Darwin Wars."

One of Gould's main critics was John Maynard Smith, a famous British evolutionary biologist. Maynard Smith thought Gould didn't give enough importance to adaptation (how living things become suited to their environment). He also felt that Gould sometimes made it sound like Darwinian evolution was being disproven, which Gould never intended. Gould later clarified some of these misunderstandings.

Another famous debate was between Gould and Richard Dawkins. Dawkins argued that natural selection is best understood as competition among genes. Gould, however, believed in "multi-level selection," meaning selection can happen at many levels, including genes, individual organisms, and even groups of species.

Cambrian Life Forms

In his book Wonderful Life (1989), Gould wrote about the strange and amazing creatures from the Cambrian period found in the Burgess Shale fossils. He highlighted their unusual body plans and how suddenly they appeared. He argued that chance played a big role in which of these early life forms survived and led to today's animals.

Other scientists, like Simon Conway Morris, disagreed with some of Gould's ideas about the Cambrian period. Conway Morris believed that many Cambrian animals were actually early forms of modern groups and that evolution might be more predictable than Gould thought.

Human Behavior and Biology

Gould also had long-running discussions with scientists like E. O. Wilson and Steven Pinker about sociobiology and evolutionary psychology. These fields suggest that many human behaviors have a strong evolutionary basis. Gould and his colleague Richard Lewontin argued that these ideas often lacked enough evidence.

Gould believed that while biology is important, human behavior is not entirely determined by our genes. He emphasized that humans have a wide range of possible behaviors. Our human brain allows us to be aggressive or peaceful, selfish or generous. He stated that "Violence, sexism, and general nastiness are biological since they represent one subset of a possible range of behaviors. But peacefulness, equality, and kindness are just as biological." He believed that creating good social structures could help positive behaviors flourish.

The Mismeasure of Man

Gould wrote The Mismeasure of Man (1981), a book that looked at the history of intelligence testing and the measurement of skulls (craniometry) in the 19th century. He argued that these practices were often based on a flawed belief called biological determinism. This is the idea that differences between human groups (like races or sexes) are mainly due to inherited, inborn traits. Gould believed that this idea was used to support social and economic inequalities.

The book caused a lot of discussion and was both praised and criticized. Later studies have re-examined the historical data Gould discussed. While some found that Gould made a few errors, they often agreed with his main point: that biases, especially racial biases, influenced how scientists interpreted their measurements in the past.

Science and Religion: Non-Overlapping Magisteria

In his book Rocks of Ages (1999), Gould proposed a way for science and religion to exist without conflict. He called this the principle of "non-overlapping magisteria" (NOMA).

He defined a magisterium as an area where a certain way of teaching has the right tools to understand and resolve questions.

- The magisterium of science covers the natural world: what the Universe is made of (facts) and how it works (theories).

- The magisterium of religion covers questions of ultimate meaning and moral values.

Gould suggested that these two areas do not overlap. He believed that science and religion should not try to comment on each other's territory. This idea has also been debated. Some, like Richard Dawkins, argue that religions often claim miracles, which would go against scientific principles. Others believe that science can also help us understand ethics and values.

See also

In Spanish: Stephen Jay Gould para niños

In Spanish: Stephen Jay Gould para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |