American Museum of Natural History facts for kids

|

|

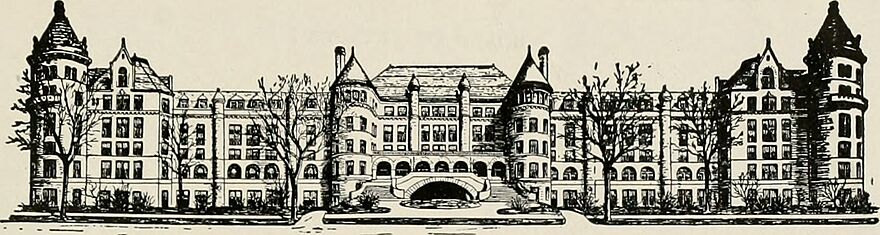

Facade of the east entrance from Central Park West

|

|

| Established | April 6, 1869 |

|---|---|

| Location | 200 Central Park West New York, N.Y. 10024 United States |

| Type | Private 501(c)(3) organization Natural history museum |

| Visitors | 5 million (2018) |

| Public transit access | New York City Bus: M7, M10, M11, M79 New York City Subway: |

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a huge and exciting natural history museum in New York City. It's located on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, right across from Central Park. The museum is made up of 21 buildings connected together. Inside, you'll find 45 permanent exhibition halls, plus a planetarium and a library.

The museum's collections hold about 32 million items! These include plants, animals, fungi, fossils, minerals, rocks, meteorites, and human cultural artifacts. There are also special collections like frozen tissues and data about genes and space. Only a small part of these amazing collections can be shown at one time. The museum covers a massive area, more than 2,500,000 square feet. AMNH has 225 full-time scientists and sends out over 120 special expeditions each year. About five million people visit the museum every year.

The AMNH is a private organization. The idea for the museum came from a naturalist named Albert S. Bickmore in 1861. After many years of hard work, the museum first opened in Central Park's Arsenal on May 22, 1871. The museum's first building, designed by Calvert Vaux and J. Wrey Mould, opened on December 22, 1877. Many new parts have been added over the years, including the main entrance in 1936 and the Rose Center for Earth and Space in 2000.

Contents

- Museum History: How it Started

- The Original Museum Building

- Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall

- Mammal Halls: Animals from Around the World

- Birds, Reptiles, and Amphibians

- Biodiversity and Environment Halls

- Human Origins and Cultural Halls

- Earth and Planetary Science Halls

- Fossil Halls: Dinosaurs and Ancient Life

- Rose Center for Earth and Space

- Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation

- Exhibitions Lab: Creating the Displays

- Research Library

- Museum Activities

- Important People at the Museum

- Around the Museum

- Images for kids

- See also

Museum History: How it Started

Early Ideas for the Museum

The idea for the American Museum of Natural History began in 1861 with a naturalist named Albert S. Bickmore. He was studying in Massachusetts and noticed that many European natural history museums were in big cities. Bickmore thought New York City would be the best place for a museum like this in the United States. For several years, he worked hard to get support for his idea. After the American Civil War ended, Bickmore asked important New Yorkers, like William E. Dodge Jr., to help fund the museum. Dodge introduced Bickmore to Theodore Roosevelt Sr., who was the father of future U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt.

People wanted a natural history museum even more after another museum, Barnum's American Museum, burned down in 1868. In December of that year, eighteen important New Yorkers wrote a letter asking for a natural history museum in Central Park. A Central Park official, Andrew Haswell Green, supported the idea in January 1869. A group of trustees was formed for the museum. The next month, Bickmore and Joseph Hodges Choate wrote a plan for the museum, which the trustees approved. This plan was the first time the name "American Museum of Natural History" was used. Bickmore wanted the name to show his hope that it would become the most important museum of its kind in the country, like the British Museum.

Building the First Museum

The law to create the museum was signed on April 6, 1869. John David Wolfe became its first president. The museum's leaders then asked if they could use the top two floors of Central Park's Arsenal. This request was approved in January 1870. Insect specimens were put on the lower floor, while stones, fossils, mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles were placed on the upper floor. The museum officially opened in the Arsenal on May 22, 1871. The AMNH quickly became very popular. In the first nine months of 1876 alone, 856,773 people visited the Arsenal location. This was more than the British Museum had in all of 1874.

Meanwhile, the museum's leaders found a new place for a permanent building. This was Manhattan Square, located between Central Park West, 81st Street, Columbus Avenue, and 77th Street. Important New Yorkers raised $500,000 to help build the new structure. The city then set aside Manhattan Square for the museum. Another $200,000 was raised for the building fund. Many important people, including U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant, attended the museum's groundbreaking ceremony on June 3, 1874.

The new museum building opened on December 22, 1877, with a ceremony attended by U.S. president Rutherford B. Hayes. The old exhibits were moved from the Arsenal in 1878. By the next year, the AMNH had no debt.

Growing in the 1800s

At first, the AMNH was reached by a temporary bridge over a ditch. It was also closed on Sundays. In May 1881, the museum's trustees decided to finish the paths from Central Park. Work started later that year. The landscape changes were almost done by mid-1882, and a bridge over Central Park West opened that November. At this point, the museum's building and the Arsenal couldn't hold any more objects. The existing spaces, like the 100-seat lecture hall, were too small.

The museum's collections kept growing in the 1880s. It also hosted many lectures throughout the 19th century. In early 1887, New York state lawmakers suggested expanding the AMNH. Thousands of teachers supported this idea. In March 1888, the trustees approved a new entrance in the middle of the 77th Street side. Many objects in the museum's collection couldn't be shown until the new part was opened. The original building was updated in 1890, and the museum's library moved to the west wing that year.

The AMNH's trustees thought about opening the museum on Sundays by February 1892. They stopped charging admission in July of that year. The museum started Sunday operations in August, and the southern entrance opened that November. Even with the new wing, there still wasn't enough space for the museum's collection. The city approved a new lecture hall in January 1893, but this was delayed in May for a wing extending east on 77th Street.

When the east wing was almost finished in February 1895, the AMNH's trustees asked for $200,000 to build a wing extending west on 77th Street. The east wing was still being prepared by August, and its ground floor opened that December. The museum's money and collections continued to grow. A hall of mammals opened in November 1896. That year, the AMNH was allowed to extend the east wing northward along Central Park West, creating an L-shaped building. The museum's director, Morris K. Jesup, also funded trips around the world to get objects for the collection. By mid-1898, the west wing, the expanded east wing, and a lecture hall were being built. The west and east wings were almost done by late 1899. A hall for ancient Mexican art opened that December.

The 1900s and Beyond

Early 1900s to 1940s

The museum's large 1,350-seat lecture hall opened in October 1900. The Native American and Mexican halls in the west wing also opened then. During the 1900s, the AMNH sent out several expeditions to add to its collection. These included trips to Mexico, the Pacific Northwest for animals, China for art, and local caves for rocks. One trip brought back a brontosaurus skeleton, which became the main attraction of the dinosaur hall that opened in February 1905.

In the early 1920s, museum president Henry Fairfield Osborn planned a new entrance for the AMNH. This entrance would honor Theodore Roosevelt. The New York state government also looked into building a Roosevelt memorial. After some discussion, New York City offered a spot next to the AMNH. In 1925, the AMNH's trustees held a design contest, choosing John Russell Pope to design the memorial hall. Construction began in 1929. Roosevelt's cousin, U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt, officially opened the memorial on January 19, 1936.

Mid-1900s to 1990s

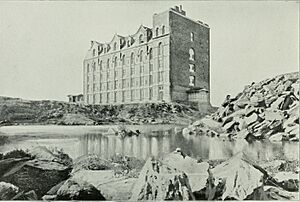

The original building was later called "Wing A." In the 1950s, the top floor was changed into a library. The ten-story Childs Frick Building, which holds the AMNH's fossil collection, was added to the museum in the 1970s.

The architect Kevin Roche and his company, Roche-Dinkeloo, have been in charge of planning for the museum since the 1990s. Many parts of the museum, both inside and out, have been updated. The Dinosaur Hall was renovated starting in 1991. The museum's Rose Center for Earth and Space was finished in 2000.

The 2000s and Today

In 2001, the museum's lecture hall was renamed the Samuel J. and Ethel LeFrak Theater. This happened after Samuel J. LeFrak gave $8 million to the AMNH. The museum's south side, along 77th Street, was cleaned and repaired, looking new again in 2009. The museum also restored a large painting in the Roosevelt Memorial Hall in 2010.

The Richard Gilder Center

In 2014, the museum shared plans for a new $325 million addition called the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation. It was named after Richard Gilder, a stockbroker and generous supporter.

On October 11, 2016, the Landmarks Preservation Commission approved the expansion. Construction of the Gilder Center began in June 2019, after some community discussions.

The Gilder Center officially opened on May 4, 2023. In the first three months, 1.5 million people visited the museum. In 2025, the AMNH started offering free "Discoverer" memberships to people who receive food assistance.

Native Remains

In late 2023, the museum announced it would stop showing human remains from its collection. Even though a law called the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was passed in 1990, the AMNH still had about 1,900 Native American remains that had not been returned by 2023.

In January 2024, the museum closed several displays and the AMNH's Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains halls. This covered about 10,000 square feet. The museum agreed to return the remains in July 2024.

The Original Museum Building

The first building, in a style called Victorian Gothic, was designed by Calvert Vaux and J. Wrey Mould. They also worked on Central Park's architecture. Their original plan was to make it look similar to the Metropolitan Museum of Art across Central Park. The first building was in the middle of the 77th Street side and was 199 feet long and 66 feet wide. It had a gallery that was 112 feet long and 200 feet tall. This gallery had a raised basement, three floors of exhibits, and an attic. The back of the gallery had two towers. The original building is still there but is now hidden by the many other buildings that make up the museum complex today. You can still enter the museum through its 77th Street entrance, now called the Grand Gallery.

The full plan for the museum was much bigger. It called for twelve buildings similar to the original one. The finished museum would have been 850 feet from north to south and 650 feet from west to east. It would have covered over 18 acres, making it the largest building in North America and the largest museum building in the world. This huge plan was never fully built. By 2015, the museum had 25 separate buildings that weren't always well connected.

The original building was soon overshadowed by the west and east wings of the southern side. These were designed by J. Cleaveland Cady in a brownstone neo-Romanesque style. This part stretches 700 feet along West 77th Street, with corner towers 150 feet tall. The pink brownstone and granite used came from quarries in New York. The southern wing has several halls. At the ends of both wings are round, tower-like structures.

Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall

The main entrance hall on Central Park West is officially called the New York State Memorial to Theodore Roosevelt. It was finished by John Russell Pope in 1936. It's a large, grand monument to former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt. This hall was originally meant to be one end of a "promenade" through Central Park, connecting to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the east, but that promenade was never finished.

The memorial hall has a pink-granite front, designed to look like Roman arches. In front of the hall on Central Park West is a terrace 350 feet long, with a series of steps. The main entrance is a huge arch 60 feet high. Inside the arch, there's a granite entryway leading to a bronze, glass, and marble screen. On each side of the arch are statues of a bison and a bear. It's also flanked by two pairs of columns, topped with figures of American explorers like John James Audubon and Meriwether Lewis. These figures, sculpted by James Earle Fraser, are about 30 feet tall. Above the main archway, there's an inscription describing Roosevelt's achievements. The words "Truth," "Knowledge," and "Vision" are carved below this inscription.

Fraser also designed an equestrian statue of Theodore Roosevelt, with a Native American and an African American figure beside him. This statue originally stood outside the memorial hall. In recent years, there were concerns about how these figures were shown. Because of this, museum officials announced in 2020 that they would remove the statue. It was removed in January 2022 and will be moved to the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in North Dakota.

The inside of the Memorial Hall is 67 by 120 feet across, with a curved ceiling 100 feet tall. The ceiling has octagon shapes, and the floors are made of mosaic marble tiles. The bottom 9 feet of the walls are covered in marble, and above that, the walls are made of limestone. Each of the Memorial Hall's four sides has two red-marble columns, each 48 feet tall. There are round windows high up on the north and south walls. William Andrew MacKay designed three large murals, 62 feet wide, showing important moments in Roosevelt's life: the building of the Panama Canal, African exploration, and the Treaty of Portsmouth. The east and west walls have four quotes from Roosevelt about "Nature," "Manhood," "Youth," and "The State."

The Memorial Hall originally connected to classrooms, exhibit rooms, and an auditorium. An entrance to the 81st Street–Museum of Natural History station is directly below the Memorial Hall. Today, the hall connects to the Akeley Hall of African Mammals and the Hall of Asian Mammals. The Memorial Hall has four exhibits that describe Theodore Roosevelt's work in conservation during different parts of his life.

Mammal Halls: Animals from Around the World

Old World Mammals

Akeley Hall of African Mammals

Named after taxidermist Carl Akeley, the Akeley Hall of African Mammals is a two-story hall on the second floor. It's right next to the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. This hall has 28 dioramas that show the many different environments in Africa and the mammals that live there. A diorama is a scene with stuffed animals and a painted background that looks very real. The main display in the hall is a group of eight African elephants in an "alarmed" pose. While mammals are the main focus, you can also see birds and plants from these regions. This hall was finished in its current form in 1936.

Carl Akeley first suggested the Hall of African Mammals to the museum around 1909. He wanted to create 40 dioramas showing the landscapes and animals of Africa, which were quickly disappearing. Akeley started collecting specimens for the hall as early as 1909. He even met Theodore Roosevelt during an expedition. After Akeley's unexpected death in 1926, James L. Clark took over finishing the hall. He hired artists like James Perry Wilson to help paint the backgrounds. The dioramas in this hall influenced the design of other animal halls in the museum.

Hall of Asian Mammals

The Hall of Asian Mammals is right south of the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. It has 8 full dioramas, 4 partial dioramas, and 6 displays of mammals and places from India, Nepal, Burma, and Malaysia. The hall opened in 1930 and, like the Akeley Hall, features two large Asian elephants in the center. At one time, a giant panda and Siberian tiger were also part of this hall's collection. These animals can now be seen in the Hall of Biodiversity.

The animals for the Hall of Asian Mammals were collected during six expeditions led by Arthur Stannard Vernay and Col. John Faunthorpe. Vernay paid for all the expeditions. The first Vernay-Faunthorpe expedition happened in 1922. Many of the animals Vernay was looking for, like the Sumatran rhinoceros and Asiatic lion, were in danger of disappearing. Artist Clarence C. Rosenkranz went on these trips and painted most of the diorama backgrounds in the hall.

New World Mammals

Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals

The Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals is on the first floor, west of the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. It has 43 dioramas showing different mammals from North America, north of tropical Mexico. Each diorama focuses on a specific animal, from huge animals to smaller rodents and carnivores. Some cool dioramas include Alaskan brown bears looking at salmon, a pair of wolves, and dueling bull Alaska moose.

The Hall of North American Mammals first opened in 1942 with only ten dioramas. Another 16 were added in 1963. A big renovation project started in late 2011 after a large gift from Jill and Lewis Bernard. In October 2012, the hall reopened as the Bernard Hall of North American Mammals.

Hall of Small Mammals

The Hall of Small Mammals is a smaller section connected to the Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals. It's right to the west of it. This hall has several small dioramas showing tiny mammals found across North America. These include collared peccaries, Abert's squirrel, and a wolverine.

Birds, Reptiles, and Amphibians

Sanford Hall of North American Birds

The Sanford Hall of North American Birds is on the third floor, between the Hall of Primates and Akeley Hall's second level. It has over 20 dioramas showing birds from across North America in their natural homes. At the far end of the hall are two large paintings by bird expert and artist Louis Agassiz Fuertes. The hall also has displays with big collections of warblers, owls, and raptors (birds of prey).

This hall was thought up by museum bird expert Frank Chapman. It's named after Chapman's friend, Leonard Cutler Sanford, who helped pay for the hall and gave his own bird collection to the museum. Work on the hall's dioramas started as early as 1902, and they opened in 1909. They were the first dioramas shown in the museum and are the oldest ones still on display. The hall was updated in 1962.

Chapman wanted his dioramas to be very realistic and show a scientific record of habitats and species that were in danger of disappearing. Each diorama showed a species, their nests, and 4 feet of the surrounding habitat in every direction.

Hall of Birds of the World

The Hall of Birds of the World is on the south side of the second floor. This hall shows the many different kinds of birds from all over the globe. 12 dioramas display various ecosystems around the world and give examples of the birds that live there. For example, you can see king penguins in a diorama of South Georgia or kookaburras in an Australian outback scene.

Whitney Memorial Hall of Oceanic Birds

The Whitney Memorial Wing, originally named after Harry Payne Whitney, opened in 1939 and contained 750,000 birds. Later known as the Hall of Oceanic Birds, it was finished and dedicated in 1953. It was started by Frank Chapman and Leonard C. Sanford, who wanted a hall to show birds from the Pacific islands. The hall was designed to be a fully immersive collection of dioramas, including a circular display of birds-of-paradise. In 1998, the Butterfly Conservatory was put inside this hall.

Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians

The Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians is near the southeast corner of the third floor. It teaches you about herpetology, which is the study of reptiles and amphibians. Many exhibits explain how reptiles evolved, their body parts, how many different kinds there are, how they reproduce, and how they behave. Cool exhibits include a group of Komodo dragons, an American alligator, Lonesome George (the last Pinta Island tortoise), and poison dart frogs.

In 1926, W. Douglas Burden and others collected Komodo Dragon specimens for the museum. The hall opened in 1927 and was rebuilt from 1969 to 1977.

Biodiversity and Environment Halls

Hall of Biodiversity

The Hall of Biodiversity is located below the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. It opened in May 1998. This hall mainly has exhibits and objects that show what biodiversity is. Biodiversity is the variety of life on Earth. It also shows how living things interact and the bad effects of extinction on biodiversity. The hall includes a 2,500-square-foot diorama showing the Dzanga-Sangha Special Reserve rainforest with over 160 animal and plant species. The diorama shows the rainforest in three ways: untouched, changed by human activity, and destroyed by human activity. Another cool part of the hall is "The Spectrum of Habitats," a video wall showing videos of nine different ecosystems. There's also a "Transformation Wall" with information about changes to biodiversity and a "Solutions Wall" with ideas on how to increase biodiversity.

Hall of North American Forests

The Hall of North American Forests is on the museum's first floor, between the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall and the Warburg Hall. It has ten dioramas showing different types of forests from across North America. It also has displays about protecting forests and tree health. The hall was built with the help of botanist Henry K. Svenson and opened in 1958. Each diorama clearly states the location and exact time of year it shows. The trees and plants in the dioramas are made from art supplies and real bark and other pieces collected from nature. At the entrance to the hall, you can see a cross-section of the Mark Twain Tree, a 1,400-year-old sequoia from California.

Warburg Hall of New York State Environments

Warburg Hall of New York State Environments is on the museum's ground floor, between the Hall of North American Forests and the Grand Hall. It focuses on the ecosystems typical of New York State, using the town of Pine Plains as an example. The hall shows different soil types, seasonal changes, and how both humans and animals affect the environment. It's named after Felix M. Warburg, a German-American supporter, and opened on May 14, 1951.

Milstein Hall of Ocean Life

The Milstein Hall of Ocean Life is in the southeast part of the first floor, west of the Hall of Biodiversity. It focuses on marine biology (ocean life), ocean plants, and marine conservation (protecting the ocean). In the center of the hall is a 94-foot-long model of a blue whale. The upper level of the hall shows the many different ecosystems in the ocean. Dioramas compare life in places like kelp forests, mangroves, and coral reefs. It tries to show how huge and varied the oceans are. The lower half of the hall has 15 large dioramas of bigger ocean animals. This is where the famous "Squid and the Whale" diorama is, showing a pretend fight between the two creatures. Another cool exhibit is the two-level Andros Coral Reef Diorama.

In 1910, museum president Henry F. Osborn suggested building a large hall for ocean life, with "models and skeletons of whales." The hall opened in 1924 and was updated in 1962. In 1969, a renovation focused more on huge ocean animals, including adding a lifelike blue whale model. The hall was renovated again in 2003, this time focusing on environmentalism and conservation. It was renamed after Paul Milstein and Irma Milstein. The 2003 renovation included fixing up the famous blue whale, updating the old dioramas, and adding electronic displays.

Human Origins and Cultural Halls

Cultural Halls

Stout Hall of Asian Peoples

The Stout Hall of Asian Peoples is on the museum's second floor, between the Hall of Asian Mammals and Birds of the World. It's named after Gardner D. Stout, a former museum president. Opened in 1980, Stout Hall is the museum's largest hall about people and cultures. It has artifacts collected by the museum between 1869 and the mid-1970s. Many famous museum expeditions are connected to the items in this hall.

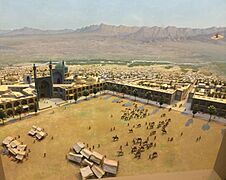

Stout Hall has two parts: Ancient Eurasia, which is a small section about how human civilization developed in Eurasia, and Traditional Asia, a much larger section with cultural items from all over Asia. The Traditional Asia section is set up to follow two major trade routes of the Silk Road. Like many museum halls, the items in Stout Hall are shown in different ways, including exhibits, small dioramas, and five full-size dioramas. Cool exhibits in the Ancient Eurasian section include copies from old archaeological sites and a full-size copy of a Hammurabi Stele. The Traditional Asia section has areas for major Asian countries like Japan, China, Tibet, and India, as well as many smaller Asian tribes.

-

A tiny diorama of Isfahan that looks like it goes on forever.

Hall of African Peoples

The Hall of African Peoples is behind Akeley Hall of African Mammals. It's organized by the four main environments in Africa: River Valley, Grasslands, Forest-Woodland, and Desert. Each section shows artifacts and exhibits about the people who live in those environments across Africa. The hall has three dioramas and cool exhibits, including a large collection of spiritual costumes. The hall also compares African societies based on hunting and gathering, farming, and raising animals. Each type of society is shown with its history, politics, spiritual beliefs, and connection to nature. A small section about the African diaspora (people spread by the slave trade) is also included.

Hall of Mexico and Central America

The Hall of Mexico and Central America is on the museum's second floor. It's behind Birds of the World and before the Hall of South American Peoples. It shows archaeological artifacts from many ancient civilizations that once lived in Mesoamerica, like the Maya, Olmec, Zapotec, and Aztec. Most of the written records from these civilizations didn't survive the Spanish conquest. So, this hall tries to piece together what we can know about them just from the artifacts.

The museum has shown ancient artifacts since it opened. Its first hall dedicated to this topic opened in 1899. As the museum's collection grew, the hall was updated in 1944 and again in 1970. Cool artifacts on display include the Kunz Axe and a full-size copy of Tomb 104 from the Monte Albán archaeological site.

South American Peoples

The Hall of South American Peoples is on the northwestern corner of the second floor, next to the Hall of Mexico and Central America. This hall first opened on the third floor in 1904. It showed archaeological objects, including mummies, from Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, and the West Indies. In 1931, the hall was made bigger and moved to the second floor. The new hall included a copy of a Chilean copper mine. In 1989, the hall was renovated and reopened as a permanent exhibit. It focuses on the skills and art of ancient Andean and traditional Amazonian cultures. The hall has about 2,300 objects from various ancient South American cultures, like the Moche and Inca. Many items on display come from the Roosevelt Collections, gathered by Theodore Roosevelt on trips to South America in the early 1900s.

Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Peoples

The Hall of Pacific Peoples is on the southwestern corner of the third floor. You can get to it through the Hall of Plains Indians. The cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead started the Hall of Pacific Peoples in 1971. She wanted the exhibit to feel like the sights and sounds of the Pacific regions. After Mead passed away in 1978, the hall reopened in December 1984 as the Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Peoples. The hall was closed again in 1997 and reopened in 2001 with an updated design.

The Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Peoples has artifacts from New Zealand, Australia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and other Pacific islands. Mead herself collected 250 of the 1,500 items in the hall. Some of these were from her fieldwork in New Guinea and other Pacific islands between 1928 and 1939. Others, like a theater set from a puppet play in Bali, were chosen from items Mead and her husband Gregory Bateson sent to the museum while they were working in Bali. The exhibits also include a fiberglass copy of an Easter Island moai statue and capes made of honeycreeper feathers.

Native American Halls

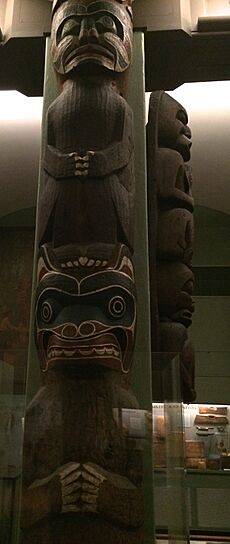

Northwest Coast Hall

The Northwest Coast Hall is on the museum's ground floor, behind the Grand Gallery. It's the museum's oldest hall, started in 1899 by anthropologist Franz Boas. The hall now has artifacts and exhibits from the tribes of the North Pacific Coast (Southern Alaska, Northern Washington, and parts of British Columbia). You'll see four "House Posts" from the Kwakwaka'wakw nation and murals by William S. Taylor showing native life. As of 2022, there are 9,000 items in total, including 78 totem poles. There's also a Haida canoe hanging from the ceiling. The artifacts have descriptions in many Native American languages.

The items in the hall came from three main sources. The first was a gift of Haida artifacts in 1882. Then the museum bought two collections of Tlingit artifacts. The rest came from the famous Jesup North Pacific Expedition between 1897 and 1902. This expedition was very important for American anthropology. Many famous experts took part, including George Hunt, who got the Kwakwaka'wakw House Posts. Other tribes featured in the hall include Coastal Salish and Nuxalk.

When it first opened, the Northwest Coast Hall was one of four halls about the native peoples of the United States and Canada. In May 2022, the hall reopened after a five-year, $19 million renovation. It now has over 1,000 artifacts on display, including work from modern artists.

Hall of Plains Indians

The Hall of Plains Indians is on the south side of the third floor, near the western end of the museum. This hall opened in February 1967. It mainly focuses on the people of the North American Great Plains in the mid-1800s. It shows cultures like the Blackfeet and Dakota. A special item is a Folsom point found in New Mexico in 1926. This shows evidence of early human settlement in the Americas.

Hall of Eastern Woodlands Indians

The Hall of Eastern Woodlands Indians is next to the Hall of Plains Indians, on the south side of the third floor. This hall opened in May 1966. It describes the lives and tools of traditional Native American peoples in the woodland areas of eastern North America. These include Cree, Mohegan, Ojibwe, and Iroquois cultures. The exhibit shows examples of native basketry, pottery, farming, food preparation, metal jewelry, musical instruments, and textiles. Other highlights include a model of a Menominee birchbark canoe and different traditional homes like an Ojibwa domed wigwam and an Iroquois longhouse. As of January 2024, this hall, along with the Hall of the Plains Indians, is closed to follow new rules about returning Native American remains.

Human Origins Halls

Anne and Bernard Spitzer Hall of Human Origins

The Anne and Bernard Spitzer Hall of Human Origins is on the south side of the first floor, near the western end of the museum. It opened with its current name on February 10, 2007. When it first opened in 1921, it was called the "Hall of the Age of Man." It was the only major exhibit in the United States to deeply explore human evolution. The displays tell the story of Homo sapiens, showing how humans evolved and where human creativity came from.

Many of the displays from the original hall can still be seen today. These include life-size dioramas of early human relatives like Australopithecus afarensis, Homo ergaster, Neanderthal, and Cro-Magnon. They show what scientists believe these species could do. You can also see full-size copies of important fossils, like the 3.2-million-year-old Lucy skeleton and the 1.7-million-year-old Turkana Boy. The hall also has copies of ice age art found in France. These limestone carvings of horses were made almost 26,000 years ago and are some of the earliest examples of human art.

Earth and Planetary Science Halls

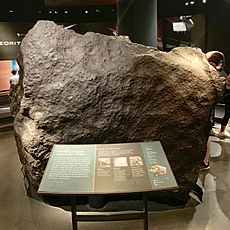

Arthur Ross Hall of Meteorites

The Arthur Ross Hall of Meteorites is on the southwest corner of the first floor. It has some of the best meteorite samples in the world. This includes Ahnighito, a piece of the 200-ton Cape York meteorite. This huge meteorite, weighing 34 tons, is the largest one displayed in the Northern Hemisphere. It's so heavy that it has special columns supporting it that go through the floor and into the bedrock below the museum!

The hall also has tiny diamonds, called nanodiamonds, that are more than 5 billion years old. These were taken from a meteorite sample using chemicals. They are so small that a quadrillion (a million billion) of them can fit into a space smaller than a sugar cube.

Allison and Roberto Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals

The Allison and Roberto Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals is on the first floor, north of the Ross Hall of Meteorites. It holds thousands of rare gems, mineral specimens, and pieces of jewelry. The halls closed in 2017 for a $32 million redesign and reopened to the public in June 2021. The new exhibits focus on telling stories, being interactive, and connecting ideas across different science areas. The halls explore topics like how different minerals formed over Earth's history, plate tectonics (how Earth's crust moves), and the stories behind specific gems.

The halls display rare samples from the museum's collection of over 100,000 pieces. These include the Star of India, the Patricia Emerald, and the DeLong Star Ruby.

-

Labradorite specimen.

-

Quartz var. agate geode.

-

Quartz var. amethyst geode.

David S. and Ruth L. Gottesman Hall of Planet Earth

The David S. and Ruth L. Gottesman Hall of Planet Earth is on the first floor at the northeast corner of the museum. Opened in 1999, it's a permanent hall about the history of Earth. It covers everything from how Earth formed to the origin of life and how humans affect the planet today. The hall was designed to answer five main questions: "How has Earth evolved? Why are there ocean basins, continents, and mountains? How do scientists read rocks? What causes climate and climate change? Why is Earth habitable?" The hall has rocks and other objects collected from 28 expeditions. The oldest rock is 4.3 billion years old! There's also a 30-seat granite amphitheater with a globe in the center of the hall.

Several sections also discuss the study of Earth systems, including geology (study of Earth's structure), glaciology (study of glaciers), atmospheric sciences (study of the atmosphere), and volcanology (study of volcanoes). The exhibit has several large rocks you can touch. The hall features cool samples of banded iron and deformed conglomerate rocks, as well as granites, sandstones, lavas, and three black smokers (underwater vents). The north section of the hall, which mainly deals with plate tectonics, is set up to look like the Earth's structure.

Fossil Halls: Dinosaurs and Ancient Life

Fossil Storage Facilities

Most of the museum's collections of mammal and dinosaur fossils are not seen by the public. They are kept in many storage areas deep inside the museum complex. The most important storage building is the ten-story Childs Frick Building, which was finished in 1973. When it was completed, the museum's collection of fossilized mammals and dinosaurs was the largest in the world, weighing 600 tons. The top three floors of the Frick Building have laboratories and offices.

Other parts of the museum also store ancient life. The Whale Bone Storage Room is a huge space where powerful cranes from the ceiling move giant fossil bones. The museum attic has even more storage, like the Elephant Room, while the tusk vault and boar vault are downstairs from the attic.

Public Fossil Displays

The amazing fossil collections that are open to the public are on the entire fourth floor of the museum. You enter the fourth floor exhibits through the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Orientation Center, which opened in 1996. On the 77th Street side, you start in the Orientation Center and follow a path that shows the evolutionary tree of life. As the tree "branches," you learn about the family relationships among animals with backbones, called cladograms. A video on the museum's fourth floor introduces you to the idea of a cladogram.

Many of the fossils on display are unique and historical. They were collected during the museum's "golden era" of worldwide expeditions (1880s–1930s). Smaller expeditions continue today, bringing in new items from places like Vietnam, Madagascar, South America, and Africa.

Fossil Halls

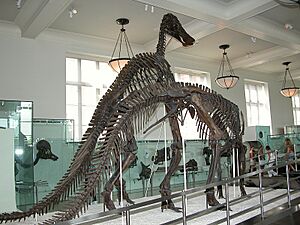

The first dinosaur hall in the museum opened in 1905. The 4th floor includes these halls:

- Hall of Saurischian Dinosaurs (these dinosaurs had grasping hands, long necks, and a certain hip bone position; they are ancestors of modern birds)

- Hall of Ornithischian Dinosaurs (these dinosaurs had a different hip bone position)

- Hall of Vertebrate Origins

- Hall of Primitive Mammals

- Hall of Advanced Mammals

The dinosaur halls were temporarily closed for renovation starting in 1990. The first halls to reopen were the primitive-mammal and advanced-mammal halls in 1994. The Halls of Saurischian Dinosaurs and Ornithischian Dinosaurs reopened in 1995 as part of a $12 million expansion. The Hall of Vertebrate Origins opened in 1996.

Fossils on Display

Some of the fossils you can see include:

- Tyrannosaurus rex: This skeleton is almost entirely made of real fossil bones. It's posed in a horizontal stalking position, balanced on its powerful legs. The specimen is actually made from parts of two T. rex skeletons found in Montana in 1902 and 1908 by the famous dinosaur hunter Barnum Brown.

- Mammuthus: This animal was larger than its relative, the woolly mammoth. These fossils are from an animal that lived 11,000 years ago in Indiana.

- Apatosaurus or Brontosaurus: This giant specimen was found in the late 1800s. Most of its fossil bones are real, but the skull is not, because none was found with it. It was many years later that the first Apatosaurus skull was discovered. A plaster copy of that skull was then placed on the museum's skeleton.

- Brontops: An extinct mammal distantly related to the horse and rhinoceros. It lived 35 million years ago in what is now South Dakota. It's known for its amazing and unusual pair of horns.

- A skeleton of Edmontosaurus annectens, a large plant-eating dinosaur. This specimen is a "mummified" dinosaur fossil, meaning that soft tissue and skin impressions were preserved in the surrounding rock. The specimen is displayed as it was found, lying on its side.

- On September 26, 2007, an 80-million-year-old fossil of an ammonite made its debut at the museum. This ammonite, 2 feet wide, is made entirely of the gemstone ammolite. Ammonites (shelled cephalopod mollusks) died out 66 million years ago, at the same time as the dinosaurs.

- One skeleton of an Allosaurus eating from a Brontosaurus corpse. This is based on fossils found with large bite marks on the Apatosaurus bones.

- The only known skull of Andrewsarchus mongoliensis.

- A display of different kinds of ground sloths, including Megalocnus rodens and Glossotherium robustus.

A Triceratops and a Stegosaurus are also on display, among many other specimens.

Besides the fossils you see in the museum, many more are stored in collections for scientists to study. These include important items like a complete diplodocid skull and tyrannosaurid teeth.

Rose Center for Earth and Space

The Hayden Planetarium, connected to the museum, is now part of the Rose Center for Earth and Space. This center is on the north side of the museum. The original Hayden Planetarium was started in 1933 with a gift from Charles Hayden and opened in 1935. The AMNH announced the modern Rose Center for Earth and Space in early 1995.

The Frederick Phineas and Sandra Priest Rose Center for Earth and Space was finished in 2000. It cost $210 million. Designed by James Stewart Polshek, the new building is a six-story glass cube. Inside, there's an 87-foot-wide glowing sphere that looks like it's floating. This sphere is called the Space Theater.

The facility has 333,500 square feet of space for research, education, and exhibits, plus the Hayden Planetarium. It also houses the Department of Astrophysics, the museum's newest science department. Neil DeGrasse Tyson is the director of the Hayden Planetarium. Polshek also designed the 1,800-square-foot Weston Pavilion, a 43-foot-high clear glass structure on the museum's west side. This smaller building offers a new entrance to the museum and more space for exhibits about space. The Heilbrun Cosmic Pathway is one of the most popular exhibits in the Rose Center.

Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation

Designed by Studio Gang and landscape architects Reed Hilderbrand, the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education and Innovation opened in May 2023. This 230,000-square-foot addition has six floors above ground and one below. The Gilder Center welcomes visitors with a new entrance on Columbus Avenue. This entrance connects to a central five-story atrium and links to more than 30 spots in the existing museum. The atrium's design is inspired by natural processes like wind and water shaping landscapes. The curved outside walls are made of the same Milford Pink granite as the museum's west side.

The Richard Gilder Center has new exhibit areas for insects, including an insectarium and a butterfly vivarium. In the vivarium, visitors can walk among hundreds of live butterflies in a lush tropical setting. It also has a visible storage area that shows scientific specimens, a bigger research library, classrooms, and laboratories. Another permanent feature is an immersive video experience called "Invisible Worlds." This focuses on the important, often hidden, connections that support life. Examples include brain neurons firing, trees exchanging nutrients, and the tiny world of plankton in the ocean.

This new part of the museum was originally planned for a different spot. It was moved and made smaller due to concerns about building in the park. The annex replaced three existing buildings along Columbus Avenue.

Exhibitions Lab: Creating the Displays

Started in 1869, the AMNH Exhibitions Lab has created thousands of displays. This department is known for combining new scientific research with amazing art and multimedia presentations. Besides the famous dioramas at the museum and the Rose Center for Earth and Space, the lab has also created international exhibits and software like the Digital Universe Atlas.

The exhibitions team currently has over sixty artists, writers, designers, and programmers. This department creates two to three exhibits each year. These big shows often travel to other natural history museums around the country. They have produced, for example, the first exhibits to discuss Darwinian evolution, human-caused climate change, and the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs.

Research Library

The Research Library is open to staff and public visitors. It's on the fourth floor of the museum. The Library collects materials on many subjects, including mammalogy (mammals), Earth and planetary science, astronomy and astrophysics, anthropology (human culture), entomology (insects), herpetology (reptiles and amphibians), ichthyology (fish), paleontology (fossils), ethology (animal behavior), ornithology (birds), mineralogy (minerals), invertebrates, systematics (classifying living things), ecology (how living things interact with their environment), oceanography (oceans), conchology (shells), exploration and travel, history of science, museology (museum studies), bibliography, genomics (genes), and other biological sciences. The collection has many old materials, some from the 15th century, that are hard to find elsewhere.

In its early years, the Library grew mostly through gifts. These included John Clarkson Jay's shell library, Carson Brevoort's library on fish, and Daniel Giraud Elliot's bird library. In the 1900s, the library continued to grow with gifts from people and groups like Joel Asaph Allen and Henry Fairfield Osborn.

The new Library was designed in 1992. The space is 55,000 square feet and has five different "conservation zones." These include a reading room for 50 people, public offices, and rooms with controlled temperature and humidity. Today, the Library's collections have over 550,000 books, magazines, pamphlets, and original illustrations. It also has film, photos, archives, manuscripts, art, and rare book collections.

Special collections include:

- Museum Archives, Manuscripts, and Personal Papers: These include documents, field notebooks, and other papers about the museum, its scientists, expeditions, exhibits, and operations.

- Art and Memorabilia Collection.

- Moving Image Collection (films and videos).

- Vertical Files: Related to exhibitions, expeditions, and museum operations.

Museum Activities

Research Activities

The museum has a scientific staff of more than 225 people. It also sponsors over 120 special field expeditions each year. Many of the fossils on display are unique and historical pieces. They were collected during the museum's "golden era" of worldwide expeditions (1880s–1930s). Examples of these expeditions include the Jesup North Pacific Expedition and the Whitney South Seas Expedition. Smaller expeditions continue today, bringing in new items from places like Vietnam, Madagascar, South America, and Africa. The museum also publishes several science journals, like the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History.

Southwestern Research Station

The AMNH runs a biological field station in Portal, Arizona, in the Chiricahua Mountains. The Southwestern Research Station was started in 1955 with a grant from David Rockefeller. It's in a place with many different kinds of plants and animals. Researchers and students use the station, and it sometimes offers classes to the public.

Educational Outreach

The AMNH has many education programs. These include reaching out to schools in New York City with the Moveable Museum. The AMNH offers a wide variety of educational programs, camps, and classes for students from pre-kindergarten to post-graduate levels. The AMNH supports the Lang Science Program, a science education program for 5th–12th graders. It also has the Science Research Mentorship Program (SRMP), where students work with an AMNH scientist on a year-long research project. As of 2023, about 400,000 schoolchildren visit the AMNH on field trips every year. While most students visit for a day, since late 2023, the museum has also offered a week-long educational program called Beyond Elementary Explorations in Science.

Richard Gilder Graduate School

On October 23, 2006, the museum started the Richard Gilder Graduate School. This made it the first American museum to give out doctoral degrees in its own name. The school is named after businessman Richard Gilder, who gave $50 million to the school. The school was officially recognized in 2009. In 2011, it had 11 students who worked closely with museum experts and could access the collections. The first seven students earned their degrees in 2013. The AMNH offers a Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT) in Earth Science and a PhD in Comparative Biology.

The MAT Earth Science Residency program started in 2012 to help with a shortage of qualified science teachers in New York state. In 2015, the MAT program officially joined the Richard Gilder Graduate School.

Important People at the Museum

Presidents

The museum's first three presidents were all co-founders. John David Wolfe served from 1869 until he passed away in 1872. He was followed by Robert L. Stuart, who left in 1881. The third president, Morris K. Jesup, was president for over 25 years, until his death in 1908. When he died, Jesup left $1 million to the museum.

The fourth president, Henry Fairfield Osborn, took over after Jesup. He helped the museum grow and expand even more.

After Osborn resigned in 1933, F. Trubee Davison became the AMNH's fifth president. Davison stepped down in 1951, and Alexander M. White was chosen as president. Gardner D. Stout then served as president from 1968 to 1975. Robert Guestier Goelet was elected after him. Goelet served until 1987. He was followed by George D. Langdon Jr., who was the first president in the museum's history to receive a salary. All previous presidents had worked without pay.

Ellen V. Futter became the museum's first female president in 1993. Futter announced in June 2022 that she planned to step down when the Gilder Center opened in March 2023. Sean M. Decatur was named as Futter's replacement in December 2022. He became the first African American president of the museum on April 3, 2023.

Other Famous Names

Famous people connected to the museum include the dinosaur-hunter of the Gobi Desert, Roy Chapman Andrews (who helped inspire the character Indiana Jones). Other notable names are biologists Ernst Mayr and Stephen Jay Gould, cultural anthropologists Franz Boas and Margaret Mead, and explorer Alexander H. Rice Jr..

Around the Museum

The museum is located at 79th Street and Central Park West. There's a direct entrance into the museum from the New York City Subway's 81st Street–Museum of Natural History station.

Outside the museum's Columbus Avenue entrance, there's a stainless steel time capsule. It was designed by Santiago Calatrava after he won a design competition. The capsule was sealed at the beginning of 2000 to mark the start of the 3rd millennium. It's shaped like a folded saddle and Calatrava described it as "a flower." This capsule is set to be opened in the year 3000.

The museum is in a 17-acre city park called Theodore Roosevelt Park. This park stretches from Central Park West to Columbus Avenue, and from West 77th to 81st Streets. It has park benches, gardens, lawns, and even a dog run. On the west side of the park, near Columbus Avenue, is the Nobel Monument. This monument honors Nobel Prize winners from the United States.

Images for kids

-

Tibetan Vajrapani statue.

-

Tibetan Kalachakra statue.

-

American bison and pronghorn diorama (right).

See also

In Spanish: Museo Americano de Historia Natural para niños

In Spanish: Museo Americano de Historia Natural para niños

- List of museums and cultural institutions in New York City

- List of most-visited museums in the United States

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

- Education in New York City

- Margaret Mead Film Festival

- Constantin Astori