Panama Canal facts for kids

9°7′12″N 79°45′0″W / 9.12000°N 79.75000°W

Quick facts for kids Panama CanalCanal de Panamá |

|

|---|---|

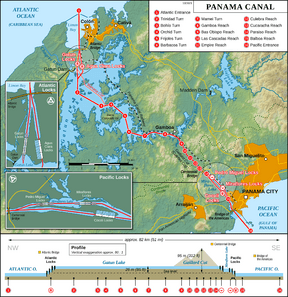

A schematic of the Panama Canal, illustrating the sequence of locks and passages

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 82 km (51 miles) |

| Maximum boat length | 366 m (1,200 ft 9 in) |

| Maximum boat beam | 49 m (160 ft 9 in) (originally 28.5 m or 93 ft 6 in) |

| Locks | 3 locks up, 3 down per transit; all three lanes (3 lanes of locks) |

| Status | Opened in 1914; expansion opened 26 June 2016 |

| Navigation authority | Panama Canal Authority |

| History | |

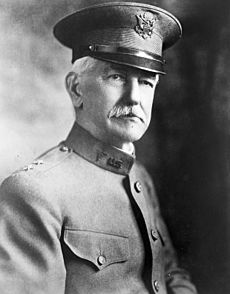

| Principal engineer | Armand Reclus and Gaston Blanchet (1881–1882), Jules Dingler (1883–1885), Maurice Hutin (1885), Philippe Bunau-Varilla (1885–1886, acting), Léo Boyer (1886), M. Nouailhac-Pioch (1886, acting), M. Jacquier (1886–1889), Philippe Bunau-Varilla (1894–1903), John Findley Wallace (1904–1905), John Frank Stevens (1905–1907), George Washington Goethals (1907–1914) |

| Construction began | 1 January 1881 |

| Date completed | 15 August 1914 |

| Date extended | 26 June 2016 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Caribbean Sea (part of Atlantic Ocean) |

| End point | Pacific Ocean |

| Connects to | Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean |

The Panama Canal (Spanish: Canal de Panamá) is an amazing artificial waterway, about 82-kilometer (51-mile) long, located in Panama. It connects the Caribbean Sea (which is part of the Atlantic Ocean) with the Pacific Ocean. This incredible shortcut helps ships avoid the long and dangerous journey around the southern tip of South America.

Building the Panama Canal was one of the biggest and most challenging engineering projects ever. It officially opened on August 15, 1914. Since then, it has made maritime travel much shorter and cheaper. This has greatly influenced global trade and helped economies grow all over the world. Today, the canal is managed and operated by the Panamanian government through the Panama Canal Authority.

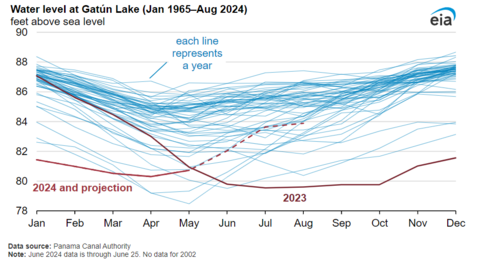

The canal uses special water elevators called locks at each end. These locks lift ships up to Gatun Lake, a large artificial freshwater lake about 26 meters (85 ft) above sea level. This lake was created by building dams on the Chagres River and Lake Alajuela. After crossing the lake, ships are lowered back down to sea level by more locks. About 200,000,000 litres (52 million US gallons) of fresh water is used for each ship that passes through. Sometimes, during dry periods, low water levels in the lake can be a challenge for the canal.

The original locks were 33.5 meters (110 ft) wide, allowing ships known as Panamax to pass. To handle even larger ships, a third, wider lane of locks was built between 2007 and 2016. This expansion opened on June 26, 2016, and now allows huge Neopanamax ships to use the canal.

Traffic through the canal has grown a lot. From about 1,000 ships in 1914, it increased to 14,702 vessels in 2008. By 2012, over 815,000 ships had used the canal. In 2017, it took ships about 11.38 hours to travel between the canal's two outer locks. The American Society of Civil Engineers has even called the Panama Canal one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World.

Contents

Exploring the Canal's History

Early Ideas for a Waterway

The idea for a canal in Panama is very old. It goes back to 1513, when the Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa first crossed the Isthmus of Panama. He thought a canal might be possible. Later, in 1534, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V ordered a study for a route to make travel between Spain and Peru easier. Many European countries saw the potential for a shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

In 1811, a German scientist named Alexander von Humboldt suggested several possible routes for a canal. He thought Nicaragua might be the best place. This idea led to the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty in 1850 between the United Kingdom and the United States. They agreed to share control of any canal built in Central America.

Meanwhile, the California Gold Rush in 1848 made people eager for a faster way to travel between the Atlantic and Pacific. An American businessman, William Henry Aspinwall, set up a route using steamships and an overland railway in Panama. This railway, built between 1850 and 1855, cost a lot of money and many workers got sick. However, it became very profitable for its owners.

France's Attempt to Build the Canal

A French diplomat named Ferdinand de Lesseps was famous for successfully building the Suez Canal in Egypt. He wanted to build another sea-level canal in Panama. In 1879, he gathered experts in Paris to discuss the project. Despite some concerns about the challenges, de Lesseps convinced many to support his plan.

Construction began on January 1, 1881. A large workforce, mostly from the Caribbean, was hired. However, the project faced huge difficulties. The tropical rainforest, heavy rains, and the need for locks made it much harder than the Suez Canal. Many workers got sick and sadly passed away from diseases like yellow fever and malaria. At the time, people didn't know that mosquitoes spread these illnesses.

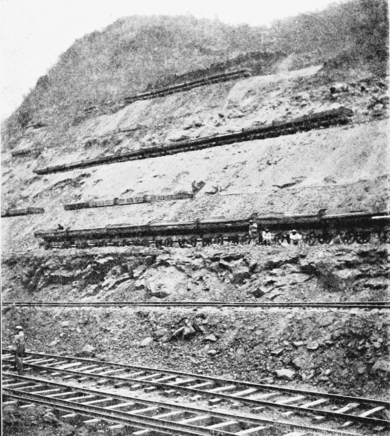

Engineers struggled with landslides in the Culebra Cut and the powerful Chagres River during the rainy season. The project ran into financial problems and eventually stopped in 1889. An estimated 22,000 workers died from diseases and accidents during this time.

In 1894, a second French company tried to restart the project. They mainly kept the existing equipment and railway in good condition, hoping to sell everything to another country.

The United States Takes Over

At the end of the 1800s, the US government also wanted to build a canal across Central America. After studying different routes, they decided that Panama was the best option, especially after the French company offered to sell its equipment and rights for $40 million.

However, Panama was then part of Colombia. The US and Colombia tried to agree on a treaty, but Colombia rejected it. So, the United States supported Panama in becoming an independent country. On November 3, 1903, Panama declared its independence. The US quickly recognized the new nation.

Soon after, on November 6, 1903, Panama and the US signed the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty. This agreement gave the United States the right to build and manage the Panama Canal Zone. Many Panamanians felt this treaty limited their new country's independence.

In 1904, the United States bought the French equipment and excavations, including the Panama Railroad, for $40 million. The US also paid Panama $10 million and an annual payment of $250,000. Later, in 1921, the US paid Colombia $25 million and granted it special privileges in the Canal Zone. In return, Colombia recognized Panama's independence.

Building the Canal: The American Way (1904–1914)

The US officially took control of the canal project on May 4, 1904. They inherited old equipment and a workforce struggling with disease. The Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC) was set up to oversee the work.

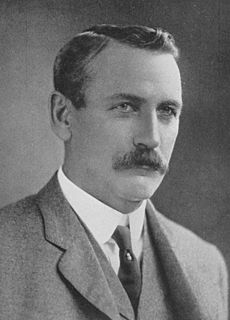

John Frank Stevens, a skilled engineer, became the chief engineer in 1905. He focused on improving living conditions for workers, building new housing, cafeterias, and water systems. He also greatly improved the railway, which was vital for moving millions of tons of earth.

A key hero was Colonel William C. Gorgas, the chief sanitation officer. He understood that mosquitoes spread diseases like yellow fever and malaria. He started huge projects to get rid of mosquito breeding areas, fumigate buildings, and install screens. Thanks to his efforts, these deadly diseases were almost eliminated. This made it much safer for workers, though about 5,600 workers still passed away from diseases and accidents during the US construction phase.

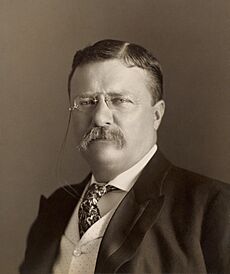

Stevens also convinced President Roosevelt that a system of locks was better than a sea-level canal. This plan involved creating Gatun Lake, which would be the largest artificial lake in the world at the time.

In 1907, George Washington Goethals, an Army engineer, took over as chief engineer. He led the project to a successful finish in 1914, two years ahead of schedule. He divided the work into three main sections: Atlantic, Central, and Pacific. The Central Division, led by Major David du Bose Gaillard, handled the toughest part: digging the Culebra Cut through the mountains.

On October 10, 1913, President Woodrow Wilson sent a telegraph signal from the White House to trigger an explosion that removed the last barrier, flooding the Culebra Cut and connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The first self-propelled vessel, Alexandre La Valley, crossed the canal in stages, reaching the Pacific on January 7, 1914. The cargo ship SS Cristobal made the first full ocean-to-ocean transit on August 3, 1914.

The Panama Canal officially opened on August 15, 1914, with the passage of the cargo ship SS Ancon. The United States spent almost $500 million to complete this massive project.

Panama Takes Control of the Canal

After World War II, many Panamanians felt that the canal and the surrounding Canal Zone should belong to Panama. Tensions grew between Panama and the United States. In 1977, President of the United States Jimmy Carter and Panama's leader Omar Torrijos signed the Torrijos–Carter Treaties. These treaties set up a plan for Panama to take full control of the canal.

On December 31, 1999, Panama officially took over the management and operation of the canal. The Panama Canal Authority (ACP) now runs this important waterway. The canal is a major source of income for Panama.

In recent years, there have been discussions about the canal's control and fees. Panama's president, José Raúl Mulino, has affirmed that the canal is an important part of Panama's heritage and is fully controlled by Panama. While some international companies operate ports near the canal, the locks and traffic control are managed by the Panamanian government.

How the Panama Canal Works

Canal Layout and Journey

The Panama Canal is a clever system of artificial lakes, channels, and locks. Even though the Atlantic Ocean is generally east of Panama and the Pacific is west, the canal actually runs from the northwest (Atlantic side) to the southeast (Pacific side) because of the shape of the land.

Here's what a ship experiences when traveling from the Atlantic to the Pacific:

- Ships enter Limón Bay from the Atlantic, a large natural harbor.

- They then go through a channel to reach the Gatun Locks.

- The Gatun Locks, a series of three steps, lift ships about 26 m (85 ft) up to the level of Gatun Lake.

- Ships then cross Gatun Lake, a huge artificial lake, for about 24 km (15 mi). This lake is fed by the Gatun River.

- Next, they enter the Culebra Cut, a channel dug through the mountains. This is where the canal crosses the continental divide.

- At the Pedro Miguel Lock, ships go down one step.

- They then cross the artificial Miraflores Lake.

- Finally, the two-step Miraflores Locks lower ships down to the Pacific Ocean.

- From the Miraflores Locks, a channel leads to Balboa harbor and then out into the Gulf of Panama in the Pacific Ocean.

The total length of the canal is about 80 km (50 mi).

Gatun Lake: The Canal's Water Source

Gatun Lake was created in 1913 by building a dam across the Chagres River. It's a very important part of the Panama Canal because it provides all the fresh water needed to operate the locks. Each time a ship passes through, millions of liters of water are used. When it was first created, Gatun Lake was the largest human-made lake in the world!

Ship Sizes and Locks

Because the canal is so important, many ships are built to fit its maximum size limits. Ships that fit the original locks are called Panamax vessels. These locks are 33.53 m (110.0 ft) wide and 320 m (1,050 ft) long. The huge steel gates of the locks are about 2 m (6.6 ft) thick and 20 m (66 ft) high.

In 2016, the canal's expansion project added larger locks. These new locks allow even bigger ships, called Neopanamax vessels, to pass through. These new locks are 55 m (180 ft) wide and 427 m (1,400 ft) long.

Paying to Pass: Canal Tolls

Just like a toll road, ships using the Panama Canal have to pay a fee, called a toll. The Panama Canal Authority sets these tolls. The amount depends on the type of ship, its size, and the kind of cargo it carries.

For example, container ships pay based on how many twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) they can carry. A TEU is the size of a standard shipping container. Passenger ships pay based on the number of beds they have. Other types of vessels pay based on their volume, measured in "PC/UMS net tons."

The lowest toll ever paid was 36 cents, by an American named Richard Halliburton who swam the Panama Canal in 1928! The most expensive regular toll was over $375,000, paid by the cruise ship Norwegian Pearl in 2010.

Expanding the Canal for the Future

Why the Canal Needed to Grow

Over time, ships became much larger than the original canal could handle. Also, more and more ships wanted to use the shortcut. Experts predicted that by 2011, many container ships would be too big for the canal. To stay important in global shipping, the canal needed to expand.

The original canal could handle about 340 million tons of shipping per year. This capacity was expected to be reached between 2009 and 2012.

The Big Expansion Project

Panama's government proposed a huge expansion plan, costing about $5.25 billion. This plan aimed to double the canal's shipping capacity. The people of Panama approved this plan in a special vote on October 22, 2006. The expansion project took place between 2007 and 2016.

The expansion involved building two new sets of locks, parallel to the old ones. One new set is on the Atlantic side (called Agua Clara locks), and the other is on the Pacific side (called Cocoli locks). These new lock chambers are much larger: 427 m (1,400 ft) long, 55 m (180 ft) wide, and 18.3 m (60 ft) deep. This allows huge Neopanamax ships, which can carry around 12,000 containers, to pass through.

A clever feature of the new locks is their water-saving basins. Each lock chamber has three basins that reuse 60 percent of the water during each transit. This means the new locks use 7 percent less water per transit than the old ones. The deepening of Gatun Lake also helps store more water.

The new locks officially opened for commercial traffic on June 26, 2016. The first ship to use them was the Chinese-owned container ship Cosco Shipping Panama. The original locks, now over 100 years old, are still in use and are carefully maintained.

Environmental Concerns and Solutions

Impacts on Nature

The Panama Canal, while great for trade, has also caused some environmental changes. These include deforestation, the spread of invasive species, and issues with water and air quality.

- Deforestation: For many years, forests in the canal's surrounding area have been cut down. This causes soil erosion, which means dirt washes into Gatun Lake and Lake Alajuela. This makes the lakes shallower and reduces their ability to hold water, which is important for both the canal and for providing drinking water to people.

- Invasive Species: The canal makes it easier for plants and animals to move between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. These "invasive species" can harm local ecosystems by competing with native species. For example, the Asian green mussel has spread through the canal.

- Pollution: Ships passing through the canal can pollute the water. Also, the heavy traffic and occasional delays mean ships burn more fuel, releasing greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide. These gases contribute to climate change.

- Water Shortage: The canal uses a lot of fresh water from Gatun Lake. About 200 million liters (52 million gallons) are needed for each ship. During dry seasons, this can lead to low water levels in the lake, affecting both canal operations and the local water supply for cities like Panama City.

Planning for More Water

Because of recent droughts that affected the canal's operations, the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) is planning to build a new reservoir on the Indio River. This project aims to provide more water for the canal and ensure it can keep operating smoothly.

The new reservoir is expected to cost about $1.6 billion and will hold a lot of water. It could help the canal handle more ships each day during dry times and provide drinking water for many people in Panama. This project is expected to begin in 2027 and take about six years to complete.

Other Ways to Cross Continents

Proposed Nicaragua Canal

For a long time, there have been ideas for another canal through Nicaragua. In 2013, a company called HKND Group announced plans to build a canal there. However, by 2018, the project had not made much progress and was largely abandoned.

Mexico's Interoceanic Corridor

Mexico has been building its own way to move goods between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. This is called the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (CIIT). It mainly uses a railway, the Tren Interoceánico, to transport cargo and passengers. This railway opened for passenger service in December 2023, and all related works were operating by July 2024.

This Mexican corridor aims to be faster than the Panama Canal for some cargo, taking about six hours to cross. It's also closer to the United States. Panama and Mexico see this corridor as a "complement" to the Panama Canal, helping to manage the busy global trade.

The Northwest Passage

Due to climate change and melting ice in the Arctic Ocean, some people think the Northwest Passage might become a new shipping route. This route goes around the north of North America and could save a lot of distance for ships traveling between Asia and Europe. However, it still has challenges with ice and other issues.

Images for kids

-

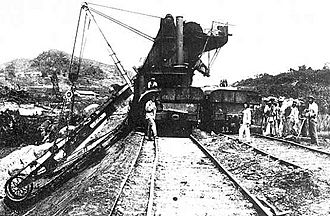

A Marion steam shovel excavating the Panama Canal, 1908

See also

In Spanish: Canal de Panamá para niños

In Spanish: Canal de Panamá para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |