Erie Canal facts for kids

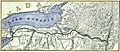

The Erie Canal is a famous canal in New York State. It stretches for 365 miles, connecting the Hudson River to Lake Erie. This amazing waterway links the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean. People first thought of building it in 1808. Construction then happened between 1818 and 1825.

The Erie Canal was the first direct route between the eastern coast of the United States and the Great Lakes. It helped many people move to western New York. It also made New York City a very important port for trade. Today, the Canal is part of the New York State Canal System.

Contents

How the Canal Worked

Boats on the canal were pulled by horses or mules. These animals walked on a special path next to the canal called a towpath. The canal had one towpath, usually on the north side.

When two boats met, one boat had to move aside. The boat with the "right of way" stayed close to the towpath. The other boat steered towards the opposite side of the canal. Its driver, called a "hoggee," would unhook the towline from the horses. The line would sink to the bottom of the canal.

The first boat's horses would then step over the sunken towline. This way, they could keep pulling their boat without stopping. Once the first boat passed, the other boat's team would continue on its way.

Even though boats moved slowly, they were very steady. This smooth way of traveling cut the journey time between Albany and Buffalo almost in half. Boats traveled day and night.

People traveled west on "packet boats" for fun or to visit family. Immigrants often rode on freight boats, sleeping on the deck. Packet boats were just for passengers. They could go up to five miles an hour. They also ran much more often than bumpy stagecoaches.

Packet boats were long, about 78 feet, and 14.5 feet wide. They used their space very cleverly. They could hold up to 40 passengers at night and even more during the day. The best boats had soft carpets, comfy chairs, and nice tables. These tables held newspapers and books.

During the day, the main cabin was like a living room. At meal times, it became a dining room. At night, a curtain divided the cabin into separate sleeping areas for ladies and gentlemen. Beds folded down from the walls, and extra cots could hang from the ceiling. Some boat captains even hired musicians for dances! The canal truly brought new ways of life to the wilderness.

Building the Erie Canal

The people who planned and built the Erie Canal were not experienced engineers. There were no trained civil engineers in the United States at that time. James Geddes and Benjamin Wright planned the route. They were judges who had some experience with surveying land for property disputes. Geddes had only used a surveying tool for a few hours before working on the Canal!

Canvass White was a young engineer, just 27 years old. He convinced Governor Clinton to let him go to Britain to study their canal systems. Nathan Roberts was a math teacher and land investor. Even with this lack of experience, these men achieved amazing things. They built the canal up the Niagara Escarpment at Lockport. They also built it over the Irondequoit Creek on a huge raised path. They even crossed the Genesee River on an impressive aqueduct. They carved a path through solid rock near Little Falls and Schenectady. All their bold plans worked exactly as they hoped.

Construction Challenges and Solutions

Building started on July 4, 1817, in Rome, New York. The first 15 miles, from Rome to Utica, opened in 1819. At that speed, the canal would have taken 30 years to finish!

The main delays were cutting down trees in thick forests and moving the dug-up soil. These tasks took longer than expected. But the builders found clever ways to solve these problems. To fell a tree, they threw a rope over its top branches. Then they used a winch to pull it down. They pulled out tree stumps with a new "stump puller." This machine used huge wheels and chains. Oxen pulled a rope around a central wheel, creating a strong force. This force ripped the stumps right out of the ground.

Soil was shoveled into large wheelbarrows. These were then dumped into carts pulled by mules. A team of three men with oxen, horses, and mules could build a mile of canal in a year.

Another challenge was finding enough workers. More and more immigrants helped fill this need. Many workers on the canal were Irish. About 5,000 Irish people had recently come to the United States. Many of them were Roman Catholic. This religion was viewed with suspicion in early America. Sadly, many workers faced violence and unfair treatment because of prejudice.

Construction sped up as new workers arrived. When the canal reached Montezuma Marsh near Syracuse, there was a rumor. People said over 1,000 workers died from "swamp fever" (malaria). Work was even stopped for a short time. However, newer studies show the death toll was likely much lower. No reports from that time mention so many deaths. Also, no mass graves have ever been found there. Work continued, and when the marsh froze in winter, crews worked to finish that section.

The middle part of the canal, from Utica to Salina (Syracuse), was finished in 1820. Boats started using it right away. Building continued east and west. The entire eastern section, 250 miles from Brockport to Albany, opened on September 10, 1823. This was celebrated with great excitement.

The Champlain Canal also opened on the same day. This was a separate 64-mile route. It ran north and south from Watervliet on the Hudson River to Lake Champlain.

In 1824, before the canal was even finished, a guide was published. It was called Pocket Guide for the Tourist and Traveler. It helped people traveling or buying land along the canal.

After Montezuma Marsh, the next big challenges were crossing Irondequoit Creek and the Genesee River near Rochester. For Irondequoit Creek, they built a huge "Great Embankment." This structure was 1,320 feet long and carried the canal 76 feet above the creek. The creek flowed through a 245-foot tunnel underneath. The Genesee River was crossed by a stone aqueduct. It was 802 feet long and 17 feet wide, with 11 arches.

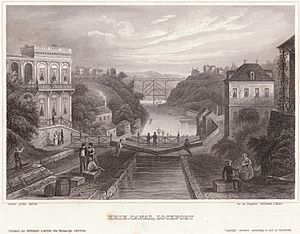

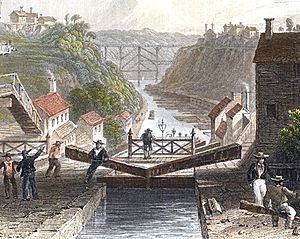

After the Genesee River, the next obstacle was the Niagara Escarpment. This was an 80-foot wall of hard limestone. To get over it to the level of Lake Erie, the canal followed a creek's path. This path had two sets of five locks in a row. This area soon became the town of Lockport. These locks lifted boats a total of 60 feet. The last part of the canal had to be cut 30 feet deep through another limestone layer. Much of this section was blasted with gunpowder. Because the crews were new to this, accidents sometimes happened. Rocks even fell on nearby homes.

Two towns wanted to be the end point of the canal: Black Rock and Buffalo. Buffalo worked hard to make Buffalo Creek wider and deeper. This created a harbor at its mouth. Buffalo won, and it grew into a large city. It eventually included Black Rock.

The entire canal was officially finished on October 26, 1825. This was celebrated with a huge "Grand Celebration" across the state. Cannons fired all along the canal and the Hudson River. It took 90 minutes for the cannon shots to travel from Buffalo to New York City!

A group of boats, led by Governor Dewitt Clinton on the Seneca Chief, sailed from Buffalo to New York City. The trip took ten days. When they arrived, Clinton famously poured water from Lake Erie into New York Harbor. This was called the "Wedding of the Waters." On its way back, the Seneca Chief carried a barrel of Atlantic Ocean water. This water was poured into Lake Erie by Buffalo's Judge Samuel Wilkeson.

The Erie Canal was completed in eight years. It cost about $7,143,000. It was praised as an amazing engineering feat. It helped unite the country and made New York City a major financial center.

The Canal's Route

The canal started on the west side of the Hudson River in Albany. It ran north to Watervliet, where the Champlain Canal branched off. At Cohoes, it climbed the land on the west side of the Hudson. Then it turned west along the south side of the Mohawk River. It crossed to the north side at Crescent and back to the south at Rexford. The canal continued west near the south side of the Mohawk River all the way to Rome. There, the Mohawk River turns north.

At Rome, the canal kept going west. It ran next to Wood Creek, which flows west into Oneida Lake. The canal then turned southwest and west across the land to avoid the lake. From Canastota west, it followed the lower edge of the Onondaga Escarpment. It passed through Syracuse, Onondaga Lake, and Rochester. Before Rochester, the canal used natural ridges to cross the deep valley of Irondequoit Creek. At Lockport, the canal turned southwest to climb to the top of the Niagara Escarpment. It used the valley of Eighteen Mile Creek.

The canal continued south-southwest to Pendleton. There, it turned west and southwest, mostly using the channel of Tonawanda Creek. From Tonawanda south towards Buffalo, it ran just east of the Niagara River. It reached its "Western Terminus" at Little Buffalo Creek. This creek later became the Commercial Slip. It flowed into the Buffalo River just before it met Lake Erie. Buffalo's Commercial Slip was dug out again in 2008. Now, the canal's original end point is filled with water and boats can use it again. However, several miles of the canal are still buried under city buildings. So, the real western end of the Erie Canal that boats can use is in Tonawanda.

The Erie Canal used New York's special landscape to its advantage. New York had the only natural break in the Appalachian Mountains south of the Saint Lawrence River. The Hudson River has tides up to Troy, and Albany is west of the Appalachians. This allowed boats to travel east-west from the coast to the Great Lakes, all within the United States.

This canal system gave New York a big advantage. It helped New York City become a global trade center. It also helped Buffalo grow from just 200 settlers in 1820 to over 18,000 people by 1840. The port of New York became the main Atlantic home port for all of the Midwest. Because of this important connection, and others like railroads later, New York became known as the "Empire State."

Changes and Improvements to the Canal

Problems came up, but they were solved quickly. Leaks appeared along the canal. These were sealed using a special cement that hardened underwater. Erosion on the clay bottom was also an issue. So, the speed limit for boats was set to 4 miles per hour.

The original canal was designed to carry 1.5 million tons of goods each year. But it carried more than that right away! So, a big project to improve the canal started in 1834. This was called the First Enlargement. During this time, the canal was made wider, from 40 feet to 70 feet. It was also made deeper, from 4 feet to 7 feet. Locks were made wider or rebuilt in new places. Many new aqueducts were also built. The canal was made straighter and its path was changed a little in some areas. This meant some short parts of the original 1825 canal were no longer used. The First Enlargement finished in 1862. More small changes were made in later years.

Today, the canal as it was after the First Enlargement is often called the "Improved Erie Canal" or the "Old Erie Canal." This helps tell it apart from the canal's modern path. The parts of the 1825 canal that were left unused are sometimes called "Clinton's Ditch." This was also a popular nickname for the whole Erie Canal project when it was first built.

More canals were soon added to connect with the Erie Canal. These "feeder canals" extended the system. They included:

- The Cayuga-Seneca Canal, going south to the Finger Lakes.

- The Oswego Canal, from Three Rivers north to Lake Ontario at Oswego.

- The Champlain Canal, from Troy north to Lake Champlain.

From 1833 to 1877, the short Crooked Lake Canal connected Keuka Lake and Seneca Lake. The Chemung Canal connected the south end of Seneca Lake to Elmira in 1833. This was an important way to bring Pennsylvania coal and timber into the canal system. The Chenango Canal in 1836 connected the Erie Canal at Utica to Binghamton. This caused a business boom in the Chenango River valley. The Chenango and Chemung canals linked the Erie with the Susquehanna River system.

The Black River Canal connected the Black River to the Erie Canal at Rome. It was used until the 1920s. The Genesee Valley Canal ran along the Genesee River. It was meant to connect with the Allegheny River at Olean. But the part that would have connected to the Ohio and Mississippi rivers was never built. The Genesee Valley Canal was later abandoned. Its path became the route for the Genesee Valley Canal Railroad.

In 1903, New York State decided to build the New York State Barge Canal. This was an improvement of the Erie, Oswego, Champlain, and Cayuga and Seneca Canals. Construction of the Barge Canal began in 1905 and finished in 1918. It cost $96.7 million.

By 1951, freight traffic on the canal reached 5.2 million tons. But then it started to decline. This was because trains and trucks became stronger competitors for moving goods.

Images for kids

-

Aqueduct over the Mohawk River at Rexford, one of 32 aqueducts on the Erie Canal

-

The Mohawk Valley, running east and west, cuts a natural pathway between the Catskill Mountains to the south and the Adirondack Mountains to the north.

-

Upstream view of the downstream lock at Lock 32, Pittsford, New York

-

Map of the "Water Level Routes" of the New York Central Railroad (purple), West Shore Railroad (red) and Erie Canal (blue)

-

Rochester, New York, aqueduct around 1890

-

The modern Erie Canal has 34 locks, which are painted with the blue and gold colors of the New York State Canal System.

-

Gateway Harbor in North Tonawanda, about 1,000 feet from the present-day western end of the Erie Canal where it connects to the Niagara River

-

The Old Erie Canal and its towpath at Kirkville, New York, within Old Erie Canal State Historic Park

-

Buffalo's Erie Canal Commercial Slip in Spring 2008

-

The modern single lock at the Niagara Escarpment

See also

In Spanish: Canal de Erie para niños

In Spanish: Canal de Erie para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |