New York Central Railroad facts for kids

|

|

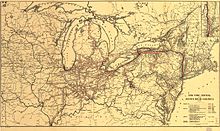

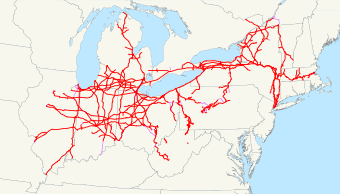

New York Central system in 1918

|

|

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | New York Central Building, New York City |

| Reporting mark | NYC |

| Locale | Illinois Indiana Kentucky Massachusetts Michigan Missouri New Jersey New York Ohio Ontario Pennsylvania Quebec Vermont West Virginia |

| Dates of operation | May 17, 1853 – January 31, 1968 |

| Successor | Penn Central Transportation Company |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

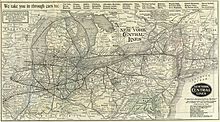

| Length | 11,584 miles (18,643 km) (1926) |

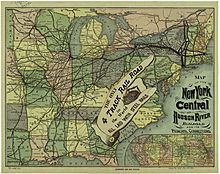

The New York Central Railroad (NYC) was a major railroad in the United States. It mainly ran trains in the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic areas. The railroad connected big cities like New York City and Boston in the east. It also reached Chicago and St. Louis in the Midwest. Other important cities on its route included Albany, Buffalo, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Detroit, and Syracuse.

The main office of the New York Central was in the New York Central Building in New York City. This building was right next to its biggest station, Grand Central Terminal. The railroad started in 1853 when many smaller companies joined together. In 1968, the NYC merged with its old competitor, the Pennsylvania Railroad. They formed a new company called Penn Central. However, Penn Central went bankrupt in 1970. It then became part of Conrail in 1976. In 1999, Conrail was split up. Most of the old New York Central tracks went to CSX.

The New York Central had many tracks in states like New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Massachusetts, and West Virginia. It also had tracks in Canada, in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec. In 1925, the NYC operated about 11,584 miles (18,643 km) of track.

Contents

How the New York Central Railroad Began

Joining Many Smaller Railroads (1826–1853)

The New York Central Railroad was not built all at once. It was formed by combining many smaller railroad companies. These companies had built tracks across New York State. One of the oldest parts was the Albany and Schenectady Railroad. It started in 1831. This line helped people and goods avoid slow parts of the Erie Canal.

Other early railroads included the Utica and Schenectady Railroad and the Syracuse and Utica Railroad. These lines slowly extended the railway network westward. They connected cities like Utica and Syracuse. At first, some of these railroads were not allowed to carry freight. This was to protect the Erie Canal's business. But later, these rules changed.

More railroads, like the Auburn and Syracuse Railroad and the Buffalo and Rochester Railroad, were built. They connected even more cities, including Auburn and Rochester. By the 1840s, there was almost a continuous rail line from Albany to Buffalo. These smaller lines often merged to form bigger ones. For example, the Tonawanda Railroad and Attica and Buffalo Railroad joined to become the Buffalo and Rochester Railroad.

Another important line was the Schenectady and Troy Railroad. It connected Schenectady to Troy on the Hudson River. The Rochester, Lockport, and Niagara Falls Railroad also joined the group. It ran from Rochester to Niagara Falls. All these smaller companies were slowly coming together.

The New York Central Railroad Forms (1853)

A businessman from Albany named Erastus Corning helped bring all these separate railroads together. On May 17, 1853, the New York Central Railroad was officially created. This merger made it one large railroad system. Soon after, other railroads like the Buffalo and State Line Railroad joined the NYC. This created a direct route to Erie, Pennsylvania.

Growing the Railroad (1853–1867)

After its formation, the New York Central continued to grow. It added more smaller railroads to its system. For example, the Rochester and Lake Ontario Railroad joined in 1855. This added a line from Rochester to Charlotte on Lake Ontario. The Buffalo and Niagara Falls Railroad also became part of the NYC in 1855.

The Lewiston Railroad and the Canandaigua and Niagara Falls Railroad were also added. These additions helped the NYC expand its reach. They connected more towns and cities in New York State.

The Hudson River Railroad

The Hudson River Railroad was another key part of the future NYC system. It started in 1846. This railroad connected Troy to New York City along the east side of the Hudson River. Cornelius Vanderbilt, a very rich businessman, took control of this railroad in 1864. He also owned the New York and Harlem Railroad.

A part of the Hudson River Railroad in Manhattan was called the West Side Line. It was built in 1934 to avoid street traffic. Today, parts of this line are used by Amtrak trains. Other sections have been turned into a beautiful park called the High Line.

The Golden Age of the New York Central

The Vanderbilt Years (1867–1954)

In 1867, Cornelius Vanderbilt gained control of the New York Central. He merged it with his Hudson River Railroad in 1869. This created the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. This new company extended the system all the way from Albany to New York City. Vanderbilt also controlled other important lines. These included the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway and the Michigan Central Railroad.

The New York Central continued to grow by adding more lines. In 1885, it took over the West Shore Railroad. This was a competing line that ran along the west side of the Hudson River. The NYC also gained control of the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad and the Boston and Albany Railroad. By 1914, many smaller companies were officially merged into the New York Central Railroad. It was often called the New York Central Lines or the New York Central System.

The Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway, also known as the Big Four, was another large railroad that joined the NYC system. It was acquired by the New York Central in 1906.

Easy Travel: The Water Level Route

The New York Central system was special because most of its main routes were very flat. This was different from its main rival, the Pennsylvania Railroad, which had many mountain routes. The NYC's main line from New York to Chicago followed rivers. This meant it had very few steep hills. This flat route was called the "Water Level Route." It was a big part of the railroad's advertising. It also influenced how their locomotives were designed.

Bypassing Busy Areas

The New York Central built many bypasses and shortcuts. These helped trains avoid busy city areas. For example, the Buffalo Belt Line opened in 1871. It allowed trains to go around Buffalo. The West Shore Railroad also provided a bypass around Rochester.

Later, the Castleton Cut-Off was built in 1924. This was a 27.5-mile-long freight bypass. It helped trains avoid the very busy West Albany area. The NYC also moved its main line in Rome, New York. This was done when the Erie Canal was widened.

Famous Trains and Locomotives

The New York Central had some of the most famous trains in the United States. Its most well-known train was the 20th Century Limited. It started in 1902. This train ran between Grand Central Terminal in New York and Chicago. It was known for its fancy service. The Century made its last trip in December 1967.

In the 1930s, the NYC introduced streamlined steam locomotives. The Commodore Vanderbilt was its first streamlined steam train. The NYC also hosted the Rexall Train in 1936. This special train toured 47 states to promote drug stores.

Other famous NYC trains included the Empire State Express and the Ohio State Limited. The Empire State Express traveled from New York City to Buffalo and Cleveland. The Ohio State Limited ran between New York City and Cincinnati.

Even though the NYC had modern steam locomotives, it started using more economical diesel-electric trains. By 1956, all the famous Niagara steam locomotives were retired. The last steam locomotive retired from service in 1957.

Here are some of the New York Central's important trains:

- 20th Century Limited: New York to Chicago (very fast, few stops)

- Commodore Vanderbilt: New York to Chicago (more stops)

- Lake Shore Limited: New York to Chicago, with service to Boston and St. Louis

- Pacemaker: New York to Chicago, an all-coach train

- Wolverine: New York to Chicago, through Canada and Detroit

The Mercuries were a group of trains that ran shorter routes:

- Chicago Mercury: Chicago to Detroit

- Cincinnati Mercury: Cleveland to Cincinnati

- Cleveland Mercury: Detroit to Cleveland

- Detroit Mercury: Cleveland to Detroit

Trains that ran from New York to St. Louis:

- Knickerbocker

- Southwestern Limited

Other notable trains:

- Empire State Express: New York to Buffalo and Cleveland

- New England States: Boston to Chicago

- Ohio State Limited: New York to Cincinnati

New York Central trains left from major stations. These included Grand Central Terminal in New York and LaSalle Street Station in Chicago. The NYC also had many local commuter lines. These served areas around New York City and Boston.

The Decline of the Railroad

Challenges After World War II

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 35,929 |

| 1933 | 20,692 |

| 1944 | 51,922 |

| 1960 | 32,329 |

| 1967 | 38,901 |

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 4,261 |

| 1933 | 2,238 |

| 1944 | 9,292 |

| 1960 | 1,797 |

| 1967 | 939 |

After World War II, the New York Central, like many U.S. railroads, faced tough times. The government heavily controlled how much railroads could charge. Also, more people started using cars and trucks. In the 1950s, airplanes became popular for long-distance travel. This took away many of the NYC's passengers.

The Interstate Highway Act of 1956 built many new highways. This made car and truck travel even easier. The opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959 also hurt the NYC's freight business. Ships could now go directly to Great Lakes ports. This meant less freight for the railroads to carry.

Railroads also had to pay high property taxes. Highways, however, did not have these taxes. Plus, there was a 15% tax on passenger tickets from World War II. This tax stayed until 1962, long after the war ended.

New Leaders and Changes (1954–1968)

In 1954, a new leader named Robert R. Young took control of the New York Central. He had big ideas for the railroad. But the company was in worse shape than he thought. Young faced many challenges. He passed away in 1958.

After Young, Alfred E. Perlman became the main leader in 1958. Perlman worked hard to make the railroad more efficient. He saved the company a lot of money. He also modernized parts of the railroad. For example, he used Centralized Traffic Control (CTC) systems. This allowed the railroad to reduce some four-track lines to two tracks. He also updated large freight yards, like the Selkirk Yard.

Perlman even experimented with jet trains. He created a special car powered by two jet engines. This was an idea to compete with cars and airplanes. However, this project never went beyond the test stage.

Perlman's cost-cutting meant some services were stopped. Commuter lines around New York were especially affected. In 1958–1959, service on the Putnam Division was suspended. The NYC also stopped its ferry service across the Hudson River. Many long-distance passenger trains were also stopped or downgraded. The famous Twentieth Century Limited made its last run in December 1967. Many of the railroad's beautiful train stations were torn down or left empty.

The End of the New York Central

Merging with the Pennsylvania Railroad

Many railroads in the Northeastern U.S. faced similar problems. There were too many railroads for the amount of traffic. The NYC had to compete with big rivals like the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O). Merging seemed like a good way to save money and reduce competition. Other railroads, like the Erie and Lackawanna, had already merged successfully.

The New York Central started looking for a merger partner in the mid-1950s. It soon became clear that the Pennsylvania Railroad was the only other company big enough for a successful merger. Both the NYC and PRR still had many passenger trains. Talks about merging started in 1955. But it took over a decade to agree. This was due to government rules, objections from unions, and concerns from other railroads.

There were two main disagreements. First, which railroad would have more control in the new company? The NYC was in better financial shape than the PRR. But the government wanted the PRR to absorb the NYC. Second, the government wanted to force the bankrupt New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad (the New Haven) into the new system. Both the NYC and PRR strongly disagreed with this. These disagreements eventually led to the new company's failure.

On January 26, 1968, the New York Central's final passenger schedule went into effect. Most long-distance passenger service had already ended in December 1967.

Penn Central: A Short-Lived Merger (1968–1976)

On February 1, 1968, the New York Central merged with the Pennsylvania Railroad. They formed the Penn Central Transportation Company. The NYC's Alfred E. Perlman became its president. The new company quickly faced problems. The government forced the money-losing New Haven railroad into Penn Central in 1969.

The merger was also handled poorly. The two companies had different ways of working. Their computer systems were not compatible. To make matters worse, the company used its savings to pay stockholders. On June 21, 1970, Penn Central declared bankruptcy. This was the largest private bankruptcy in the U.S. at that time. This bankruptcy also caused many other Northeastern railroads to go bankrupt.

Penn Central's failure showed that private companies could no longer run passenger rail service alone. In response, President Richard Nixon signed a law in 1970. This law created Amtrak. Amtrak is a government-supported railroad system. On May 1, 1971, Amtrak took over most long-distance passenger trains in the U.S. Penn Central and other railroads still had to run commuter services. They eventually handed these over to Conrail in 1976.

Conrail and CSX: What Remains Today (1976–Present)

Conrail was created by the U.S. government. Its job was to save the freight business of Penn Central and other bankrupt railroads. Conrail started operations on April 1, 1976. It took control of Penn Central's commuter lines. In 1983, these commuter services were given to state-funded agencies. These included Metro-North Railroad in New York and Connecticut.

Conrail became profitable by the 1990s. In 1999, its assets were split between CSX and Norfolk Southern. Most of the old New York Central system went to CSX.

Even though Conrail abandoned some tracks, most of the NYC system is still used today. Both CSX and Amtrak use these lines. The famous "Water Level Route" between New York and Chicago is still in use. The old NYC (now CSX) Selkirk Yard is one of the busiest freight yards in the country. In 1998, a part of Conrail was formed as New York Central Lines LLC. This subsidiary contained the old Water Level Route and other NYC lines. CSX later fully absorbed this company.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |