Culebra Cut facts for kids

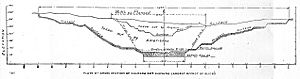

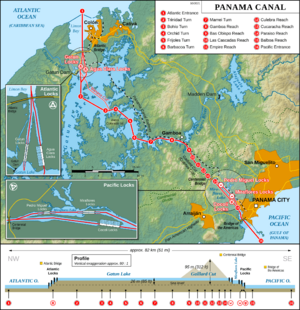

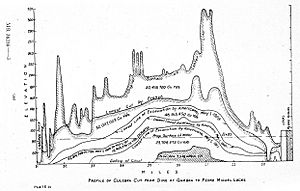

The Culebra Cut, once known as the Gaillard Cut, is a man-made valley that slices through the Continental Divide in Panama. This important cut is a key part of the Panama Canal. It connects Gatun Lake (which leads to the Atlantic Ocean) with the Gulf of Panama (which leads to the Pacific Ocean). The cut is about 7.8 miles (12.6 km) long. It stretches from the Pedro Miguel lock on the Pacific side to the Chagres River arm of Lake Gatun. The water level in the cut is 85 feet (26 meters) above sea level.

Building the Culebra Cut was one of the greatest engineering achievements of its time. It took a huge amount of effort to complete. This effort was necessary because the canal was so important for shipping. It was also very important for the strategic interests of the United States.

The name Culebra comes from the mountain ridge it cuts through. This name was first used for the cut itself. From 1915 to 2000, the cut was called Gaillard Cut. This was to honor US Major David du Bose Gaillard, who led the digging work. After the canal was given to Panama in 2000, the name went back to Culebra. In Spanish, it is known as the Corte Culebra, which also means the Snake Cut.

Building the Cut

French Efforts

The digging of the Culebra Cut began with a French company. This group was led by Ferdinand de Lesseps. They wanted to build a canal at sea level, meaning it would not use locks. The bottom of their planned canal was to be 22 meters (72 feet) wide. Digging at Culebra started on January 22, 1881.

However, the French effort faced many problems. These included widespread disease, underestimating the difficulty of the project, and money troubles. These issues led to the collapse of their work. The United States bought out the French project in 1904. The French had already dug out about 14.25 million cubic meters (18.6 million cubic yards) of material from the cut. They had also lowered the highest point from 64 meters (210 feet) to 59 meters (194 feet) above sea level. This was over a fairly narrow section.

American Efforts

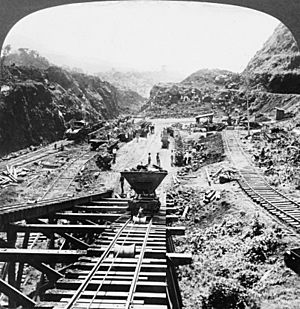

The United States took over the project on May 4, 1904. Under the leadership of John F. Stevens and later George Washington Goethals, the Americans started work on a wider but shallower cut. This was part of a new plan for a canal that would use locks to raise and lower ships. The bottom of the canal would be 91 meters (299 feet) wide. This plan meant creating a valley up to 540 meters (0.34 miles) wide at the top.

A huge amount of new earthmoving equipment was brought in. A complex system of railways was built to remove the massive amounts of dirt and rock. Major David du Bose Gaillard, from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, joined the project with Goethals. He was put in charge of the central part of the canal. This included all the work between Gatun Lake and the Pedro Miguel locks, especially the Culebra Cut. Gaillard was known for his dedication and calm, clear leadership in this difficult task.

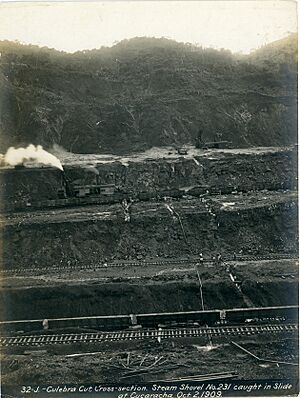

The amount of work was enormous. Many air compressor stations were built, using about 30 miles (48 km) of pipes. These pipes powered hundreds of compressed air drills. These drills made holes for 400,000 pounds (181,437 kg) of dynamite each month. The dynamite was used to blast and break up the rock in the cut. Then, steam shovels would dig out the broken rock. Most of these shovels were made by the Bucyrus Foundry and Manufacturing Company.

Dozens of trains carried the excavated dirt and rock to dumps about 12 miles (19 km) away. On a typical day, 160 trainloads of material were hauled away from the 9-mile (14 km) cut. This huge workload on the railroads needed very careful planning. At the busiest times, a train was either entering or leaving almost every minute.

Six thousand men worked in the cut. They drilled holes, placed explosives, operated steam shovels, and ran the dirt trains. They also moved and extended the railroad tracks as the work progressed. Twice a day, work stopped for blasting. After the blasts, the steam shovels moved in to clear away the loose dirt and rock. More than 600 holes filled with dynamite were set off daily. In total, 60 million pounds (27,215 metric tons) of dynamite were used. In some places, about 52,000 pounds (23.6 metric tons) of dynamite were used for a single blast.

Landslides

Digging the cut was one of the most uncertain parts of building the canal. This was because of unexpected large landslides. Experts had wrongly thought the rock would be stable at a height of 73.5 meters (241 feet) with a certain slope. In reality, the rock began to collapse at a height of only 19.5 meters (64 feet). This mistake happened partly because the iron layers underground started to rust due to water seeping in. This made the ground weak and caused it to collapse. Also, the clay-like layers of rock underneath became weaker, causing the slides to continue.

The first and largest major slide happened in 1907 at Cucaracha. A crack was first seen on October 4, 1907. Then, about 500,000 cubic yards (382,277 cubic meters) of clay slid down. This slide made many people think that building the Panama Canal would be impossible. Gaillard described the slides as "tropical glaciers," but made of mud instead of ice. The clay was too soft for the steam shovels to dig. So, it was mostly removed by washing it away with water from a high level.

After this, the dirt and rock in the upper parts of the cut were removed. This reduced the weight on the weak layers below. Landslides continued to be a problem even after the canal opened. They caused the canal to close sometimes.

Completion of the Cut

Steam shovels finally broke through the Culebra Cut on May 20, 1913. The Americans had lowered the highest point of the cut from 194 feet (59 meters) to 39 feet (12 meters) above sea level. At the same time, they made it much wider. They had dug out over 76 million cubic meters (99 million cubic yards) of material. About 23 million cubic meters (30 million cubic yards) of this material was extra. This extra material had been brought into the cut by the landslides.

Gaillard was promoted to colonel in 1913. One month later, on December 5, he died from a brain tumor in Baltimore, Maryland. So, he did not live to see the canal open in 1914. The Culebra Cut was renamed the Gaillard Cut on April 27, 1915, to honor him. After the canal was given to Panama in 2000, the old name Culebra Cut was used again.

See also

In Spanish: Corte Culebra para niños

In Spanish: Corte Culebra para niños

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Canal Zone

- Earthworks (engineering)

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |