History of the Panama Canal facts for kids

Imagine a shortcut for ships between two huge oceans! That's exactly what the Panama Canal is. The idea for this amazing waterway started way back in 1517. That's when Vasco Núñez de Balboa first crossed the narrow strip of land called the isthmus of Panama. This thin bridge of land between North and South America was the perfect spot to dig a water path. It would connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Early European explorers saw this potential, and many ideas for a canal were suggested.

By the late 1800s, new technology and a strong need for faster shipping made construction possible. A famous canal builder named Ferdinand de Lesseps led France's first attempt. They wanted to build a canal at sea-level, meaning no locks. But the project faced huge problems. Digging through the tough land was much harder than expected. Many workers got sick and died from tropical diseases. There were also problems with money and management in France. Because of all this, the French only partly finished the canal.

After France gave up, the United States became interested in building the canal. At first, the Panama location wasn't popular in the U.S. This was partly because of France's failure. Also, the government of Colombia, which owned Panama at the time, wasn't friendly to the U.S. continuing the project. So, the U.S. first looked into building a canal through Nicaragua.

A French engineer named Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla helped change American minds. He had invested a lot in the failed French canal company. He would only make money if the Panama Canal was finished. He worked hard to convince American lawmakers. He also supported a group in Panama that wanted independence from Colombia. This led to a revolution in Panama. Then, the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty was signed. This treaty gave Panama its independence and allowed the U.S. to build the canal. The U.S. military was present, which helped Panama gain independence. The new Panamanian government had to accept the canal treaty on U.S. terms.

The Americans succeeded for two main reasons. First, they changed the plan from a sea-level canal to one with locks. This made the huge digging job much more realistic. Second, they learned how to control the diseases that had killed so many workers during the French attempt. The first chief engineer, John Frank Stevens, built much of the needed infrastructure. Later, George Washington Goethals took over. Goethals oversaw most of the digging. He put Major David du Bose Gaillard in charge of the hardest part, the Culebra Cut. This was a massive trench through the toughest land.

Just as important as the engineering was the healthcare. William C. Gorgas, an expert in tropical diseases like yellow fever and malaria, led these efforts. Gorgas was one of the first to realize that mosquitoes spread these diseases. By focusing on controlling mosquitoes, he made working conditions much safer.

On January 7, 1914, a French crane boat called Alexandre La Valley was the first to travel through the canal. On April 1, 1914, construction was officially finished. The project was handed over to the Canal Zone government. The start of World War I stopped any big opening celebration. But the canal officially opened for ships on August 15, 1914. The first commercial ship to pass through was the SS Ancon.

During World War II, the canal was very important for the American military. It allowed ships to move easily between the Atlantic and Pacific. The canal remained a U.S. territory until 1977. That's when the Torrijos–Carter Treaties started the process of giving control of the Panama Canal Zone to Panama. This process was completed on December 31, 1999.

Today, the Panama Canal is still a busy and important waterway for world shipping. It is regularly updated. A new Panama Canal expansion project began in 2007 and opened on June 26, 2016. The new, larger locks allow bigger ships, called New Panamax ships, to pass through. These ships can carry much more cargo than the original locks could handle.

Contents

The French Attempt to Build the Canal

The idea of a canal across Central America became popular again in the early 1800s. In 1819, the Spanish government even approved building a canal.

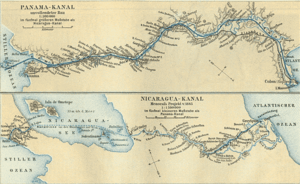

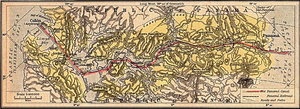

Even though the project paused, many surveys were done between 1850 and 1875. They showed that the best routes were across Panama (which was part of Colombia then) and Nicaragua. A third option was across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico.

Starting the French Project

After the Suez Canal was finished in 1869, France believed a similar project in Panama would be easy. In 1876, an international company was formed to build it. Two years later, they got permission from the Colombian government to dig a canal. Panama was a Colombian province at the time.

On March 20, 1878, the company received an exclusive 15-year contract from Colombia. This contract allowed them to build a canal across the Isthmus of Panama. The waterway would return to the Colombian government after 99 years.

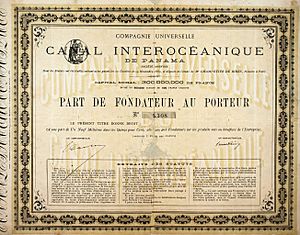

Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had built the Suez Canal, led this new project. His energy and fame convinced many people to invest almost $400 million.

However, Lesseps was not an engineer. The Suez Canal was mostly a ditch through flat, sandy desert. Building it was not very difficult. But Panama's mountains were different. Even at their lowest point, they were 110 meters (360 feet) above sea level. A sea-level canal, as Lesseps wanted, would need huge amounts of digging through unstable rock.

Other problems included rivers crossing the canal route, especially the Chagres River. This river flowed very strongly during the rainy season. If its water flowed into the canal, it would be dangerous for ships. So, a sea-level canal would need the river to be moved.

The most serious problem was tropical diseases, like malaria and yellow fever. At the time, no one knew how these diseases spread. Hospital beds were placed in cans of water to stop insects. But this stagnant water became a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes, which carry the diseases.

In May 1879, an international meeting about the canal happened in Paris. Lesseps led it. Among the 136 delegates, only 42 were engineers. The others were investors, politicians, and Lesseps' friends. Lesseps wanted this meeting to help raise money for his plan. He was sure a sea-level canal could be built as easily as the Suez Canal.

In reality, only 19 engineers approved his plan. Only one of them had ever visited Central America. American delegates did not vote because they had their own plan for a canal through Nicaragua. Five French engineers refused to approve the plan.

One of these engineers was Adolphe Godin de Lépinay. He was the only one to suggest a plan using lakes and locks. He had experience building canals and railways in difficult places. He had seen two-thirds of his workers die from tropical disease on a railway project in Mexico.

Godin de Lépinay's plan was to build a dam across the Chagres River near the Atlantic. Another dam would be built on the Rio Grande near the Pacific. This would create an artificial lake accessed by locks. His priority was less digging and avoiding unhealthy work conditions and floods. He estimated his plan would cost much less and save 50,000 lives. Sadly, his plan was not taken seriously. If it had been, the French might have finished the Panama Canal.

After the meeting, Lesseps' company bought the rights to build the canal.

The engineering meeting estimated Lesseps' project would cost $214 million. Later, an engineering group changed the estimate to $168.6 million. Lesseps then lowered this estimate twice without good reason. He also said the canal would take six years to build, even though the Suez Canal took ten.

The proposed sea-level canal would be 9 meters (30 feet) deep. It would be 22 meters (72 feet) wide at the bottom and about 27.5 meters (90 feet) wide at the water level. They estimated they would need to dig 120,000,000 cubic meters (157,000,000 cubic yards) of material. A dam was suggested at Gamboa to control the Chagres River. But this dam was later found to be impossible to build.

French Construction Begins

Construction of the canal started on January 1, 1881. Digging at Culebra began on January 22. A large workforce was put together. By 1888, there were about 40,000 workers. Most of them were from the Caribbean islands. Many French engineers came to work, but it was hard to keep them because of disease. From 1881 to 1889, over 22,000 workers died. About 5,000 of these were French citizens.

By 1885, many realized that a sea-level canal was not practical. An elevated canal with locks seemed better. But de Lesseps did not agree. A lock canal plan was finally adopted in October 1887. By this time, more and more workers were dying. There were also financial and engineering problems, along with frequent floods and mudslides. It was clear the project was in serious trouble. Work continued under the new plan until May 15, 1889. Then, the company went bankrupt, and the project stopped. After eight years, the canal was about two-fifths finished. About $234.8 million had been spent.

The company's failure caused a big scandal in France. The project was suspended.

New French Canal Company

It soon became clear that the only way for investors to get their money back was to finish the project. A new agreement was made with Colombia. In 1894, the Compagnie Nouvelle du Canal de Panama was created to finish the canal. To meet the contract terms, work started again on the Culebra excavation. A team of engineers also began a full study of the project. They eventually decided on a plan for a two-level canal with locks.

This new effort never really took off. This was mainly because the U.S. was thinking about building a canal through Nicaragua. The most workers on this new project was 3,600 in 1896. Their main job was to follow the contract terms and keep the existing digging and equipment in good condition for sale. The company was already looking for a buyer, asking for $109 million.

In the U.S., a special commission was set up in 1899 to study canal options in Central America. In November 1901, the commission said a U.S. canal should be built through Nicaragua. This was unless the French were willing to sell their holdings for $40 million. This recommendation became law on June 28, 1902. The New Panama Canal Company had to sell at that price.

What the French Achieved

Even though the French effort failed, it wasn't completely useless. The old and new companies dug out 59,747,638 cubic meters (78,146,960 cubic yards) of material. About 14,255,890 cubic meters (18,644,560 cubic yards) of this came from the Culebra Cut. The old company also dug a channel from Panama Bay to the port at Balboa. The channel dug on the Atlantic side was useful for bringing in sand and stone for the locks and spillway concrete at Gatún.

Detailed surveys and studies by the new company, along with machinery like railroad equipment, helped the later American effort. The French lowered the highest point of the Culebra Cut by 5 meters (16 feet), from 64 meters (210 feet) to 59 meters (194 feet). The Americans could use about 22,713,396 cubic meters (29,706,000 cubic yards) of excavation, worth about $25.4 million. They also used equipment and surveys worth about $17.4 million.

The United States Takes Over

Theodore Roosevelt believed that a U.S.-controlled canal across Central America was very important for the country's safety. This idea became even stronger after the USS Maine sank in Cuba in 1898. Roosevelt pushed for the U.S. to buy the French Panama Canal project. The purchase of the French land for $40 million was approved on June 28, 1902. Since Panama was part of Colombia then, Roosevelt started talking with Colombia to get the necessary rights. In early 1903, the Hay–Herrán Treaty was signed. But the Colombian Senate did not approve it.

Roosevelt suggested to Panamanian rebels that if they revolted, the U.S. Navy would help them. Panama declared its independence on November 3, 1903. The USS Nashville stopped Colombian forces from interfering. The victorious Panamanians gave the U.S. control of the Panama Canal Zone on February 23, 1904. This was for $10 million, as agreed in the November 18, 1903 Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty.

Starting the American Project

The U.S. took control of the French canal property on May 4, 1904. The new Panama Canal Zone was managed by the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC) during construction.

The first step was to put all canal workers under the new U.S. administration. The work was kept to a minimum to follow the canal agreement and keep the machinery working. The U.S. took over a small workforce and many old buildings, roads, and equipment. Much of it had been ignored for 15 years in the humid jungle. There were no good facilities for a large workforce, and everything was falling apart.

Counting all the assets was a huge job. It took many weeks to list all the available equipment. About 2,150 buildings were acquired, but many were not livable. Housing was a big problem at first. The Panama Canal Railway was also in bad shape. However, much equipment, like trains and dredges, could still be used.

Chief engineer John Findley Wallace was pushed to restart construction. But rules from Washington made it hard for him to get heavy equipment. This caused problems between Wallace and the ICC. He and chief health officer William C. Gorgas were frustrated by delays. Wallace resigned in 1905. He was replaced by John Frank Stevens, who arrived on July 26, 1905. Stevens quickly realized that a lot of money needed to be spent on infrastructure. He decided to upgrade the railway, improve sanitation in Panama City and Colón, fix old French buildings, and build hundreds of new homes. Then he started the hard job of finding enough workers. Stevens' plan was to get things done first and get approval later. He improved the drilling and dirt-removal equipment at the Culebra Cut.

No decision had been made yet about whether the canal would have locks or be sea-level. The digging already happening would be useful either way. In late 1905, President Roosevelt sent engineers to Panama to study both options. Even though the engineers voted for a sea-level canal, Stevens and the ICC disagreed. Stevens' report helped convince Roosevelt that a lock canal was better, and Congress agreed. In November 1906, Roosevelt visited Panama. This was the first time a sitting U.S. president traveled outside the country.

There was debate about whether private companies or government workers should build the canal. Bids for construction were opened in January 1907. A contractor named William J. Oliver was the lowest bidder. Stevens did not like Oliver and strongly opposed choosing him. Roosevelt first favored using a contractor. But he later decided that army engineers should do the work. He appointed Major George Washington Goethals as chief engineer in February 1907. Stevens, frustrated by government delays and army involvement, resigned. Goethals replaced him.

Living Conditions and Health

The Canal Zone at first had very few facilities for workers. The tough conditions made many American workers go home each year.

A program of improvements was started. Clubhouses were built, managed by the YMCA. They had billiard rooms, reading rooms, bowling alleys, and places for camera clubs. They also had gyms, ice cream parlors, and libraries. Members paid ten dollars a year. The rest of the upkeep was paid by the ICC. The commission built baseball fields and arranged train travel to games. A competitive league quickly formed. Dances were held twice a month at the Hotel Tivoli.

These changes made a big difference in the Canal Zone. The number of workers leaving the project each year dropped a lot.

Building the Canal with the U.S.

The work done before Goethals took over was mostly preparation. By the time he arrived, the construction setup was ready. He could soon begin building the canal in earnest.

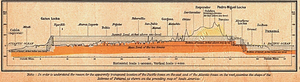

Goethals divided the project into three parts: Atlantic, Central, and Pacific. The Atlantic Division built the breakwater at Limon Bay, the Gatún locks, and the Gatun Dam. The Pacific Division built the Pacific entrance, including a breakwater in Panama Bay, and the Miraflores and Pedro Miguel locks. The Central Division had the biggest challenge: digging the Culebra Cut. This involved cutting 8 miles (13 km) across the continental divide down to 12 meters (40 feet) above sea level.

By August 1907, workers were digging out 765,000 cubic meters (1,000,000 cubic yards) per month. This was a record for the rainy season. Soon after, this amount doubled, then increased again. At its busiest, 2,300,000 cubic meters (3,000,000 cubic yards) were being dug out each month.

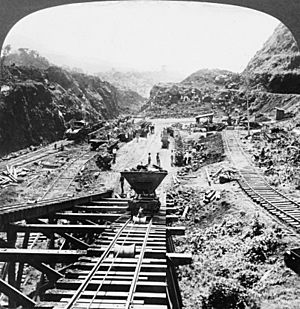

The Culebra Cut

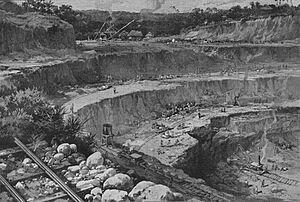

One of the biggest obstacles to building the canal was the continental divide. This mountain range was originally 110 meters (360 feet) high at its tallest point. Cutting through this rock barrier was one of the project's greatest challenges.

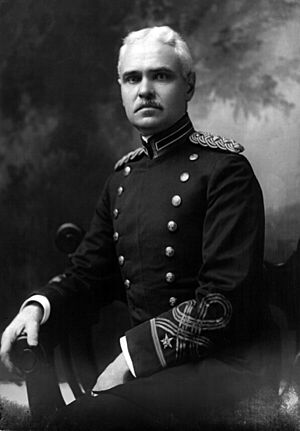

Major David du Bose Gaillard was put in charge of the Central Division. This part of the canal stretched from the Pedro Miguel locks to the Gatun Dam. Gaillard focused on getting the Culebra Cut dug.

The work was enormous. Six thousand men worked in the cut. They drilled holes for 27,000 tons (60,000,000 pounds) of dynamite to break up the rock. Then, as many as 160 trains a day removed the broken rock. Landslides happened often because the rock's iron layers weakened. Even with the huge job and frequent, unpredictable slides, Gaillard provided calm and clear leadership.

On May 20, 1913, steam shovels made a path through the Culebra Cut at the canal's bottom level. The French had lowered the summit to 59 meters (194 feet) over a narrow width. The Americans lowered it to 12 meters (40 feet) above sea level over a wider area. They dug out over 76,000,000 cubic meters (99,000,000 cubic yards) of material. About 23,000,000 cubic meters (30,000,000 cubic yards) of this was extra digging due to landslides. Dry digging ended on September 10, 1913. A landslide in January added 1,500,000 cubic meters (2,000,000 cubic yards) of earth. But it was decided this loose material would be removed by dredging when the cut was filled with water.

Dams and Lakes

Two artificial lakes are key parts of the canal: Gatun and Miraflores Lakes. Four dams were built to create them. Two small dams at Miraflores hold back Miraflores Lake. A dam at Pedro Miguel closes off the south end of the Culebra Cut, which is like an arm of Lake Gatun. The Gatun Dam is the main dam. It blocks the original path of the Chagres River, creating Gatun Lake.

The Miraflores dams include an 825-meter (2,707-foot) earth dam connecting the Miraflores Locks. There's also a 150-meter (490-foot) concrete spillway dam east of the locks. The concrete dam has eight floodgates, like those on the Gatun spillway. The Pedro Miguel dam is an earthen dam, 430 meters (1,410 feet) long. It extends from a hill in the west to the lock. Its front is protected by rock at the water level. The largest and most challenging dam is the Gatun Dam. This earthen dam is 640 meters (2,100 feet) thick at the base and 2,300 meters (7,500 feet) long at the top. It was the largest of its kind in the world when the canal opened.

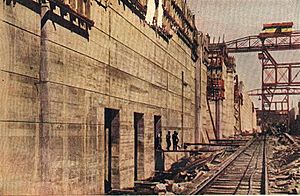

The Locks

The original plan for the lock canal included two sets of locks at Sosa Hill. It also had a long Sosa Lake extending to Pedro Miguel. In late 1907, it was decided to move the Sosa Hill locks further inland to Miraflores. This new site had a more stable foundation for building. The small Miraflores Lake that resulted became a source of fresh water for Panama City.

Building the locks began with the first concrete laid at Gatun on August 24, 1909. The Gatun locks are built into a hill next to the lake. This required digging out 3,800,000 cubic meters (5,000,000 cubic yards) of material, mostly rock. The locks were made of 1,564,400 cubic meters (2,046,000 cubic yards) of concrete. A large system of electric railways and aerial lifts carried concrete to the construction sites.

The Pacific-side locks were finished first. The Pedro Miguel lock was done in 1911, and Miraflores in May 1913. The tugboat Gatun, used to pull barges, went through the Gatun locks on September 26, 1913. The trip was successful, even though the valves were controlled by hand. The main control board was not ready yet.

Opening the Canal

On October 10, 1913, the dike at Gamboa was destroyed. This dike had kept the Culebra Cut separate from Gatun Lake. President Woodrow Wilson in Washington set off the explosion by telegraph. On January 7, 1914, the Alexandre La Valley, an old French crane boat, became the first ship to travel completely through the Panama Canal on its own power. It had worked its way across during the final stages of construction.

As construction ended, the canal team began to break up. Thousands of workers were laid off. Entire towns were taken apart or torn down. Chief health officer William C. Gorgas left to fight pneumonia in South African gold mines. He later became the Surgeon General of the Army. On April 1, 1914, the Isthmian Canal Commission was disbanded. The zone was then governed by a Canal Zone Governor. The first governor was George Washington Goethals.

A big celebration was planned for the canal's opening. But the start of World War I forced the cancellation of the main events. It became a small local affair. The steamship SS Ancon, guided by Captain John A. Constantine, made the first official trip on August 15, 1914. No international guests were there. Goethals followed the Ancon by train.

Looking Back at the Project

The canal was an amazing feat of technology. It was also very important for the U.S. military and economy. It changed world shipping routes. Ships no longer needed to sail all the way around South America, past Drake Passage and Cape Horn. The canal saves about 7,800 miles (12,600 km) on a sea trip from New York to San Francisco.

The canal's military importance was proven during World War II. It helped the U.S. move its ships between the Atlantic and Pacific. Some of the largest U.S. ships, like the Essex class aircraft carriers, barely fit through the locks. They were so big that lampposts along the canal had to be removed for them to pass.

The Panama Canal cost the U.S. about $375 million. This included $10 million paid to Panama and $40 million paid to the French company. Even though it was the most expensive construction project in U.S. history at the time, it cost about $23 million less than the 1907 estimate. This was despite landslides and making the canal wider. An extra $12 million was spent on defenses.

Over 75,000 people worked on the project. At the busiest time, there were 40,000 workers. Hospital records show that 5,609 workers died from disease and accidents during the American construction period.

The Americans dug out 182,610,550 cubic meters (238,845,580 cubic yards) of material. This includes the channels leading to the canal ends. Adding the work done by the French, the total digging was about 204,900,000 cubic meters (268,000,000 cubic yards). This is more than 25 times the amount dug for the Channel Tunnel.

Of the three presidents during the construction, Theodore Roosevelt is most connected with the canal. Woodrow Wilson was president when it opened. However, William Howard Taft might have helped the canal the most for the longest time. Taft visited Panama five times as Roosevelt's Secretary of War and twice as president. He hired John Stevens and later suggested Goethals as Stevens' replacement. Taft became president in 1909, when the canal was half finished. He was in office for most of the rest of the work. But Goethals later wrote: "The real builder of the Panama Canal was Theodore Roosevelt."

These words by Roosevelt are displayed in the administration building of the canal in Balboa:

It is not the critic who counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbled, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena; whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly, who errs and comes short again and again; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, and spends himself in a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows in the end the triumph of high achievement; and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.

David du Bose Gaillard died on December 5, 1913, at age 54. He had been promoted to colonel just a month before. Gaillard never saw the opening of the canal he helped build. The Culebra Cut was renamed the Gaillard Cut on April 27, 1915, in his honor. A plaque remembering Gaillard's work was over the cut for many years. In 1998, it was moved to the administration building, near a memorial to Goethals.

The Canal Today and Its Future

After construction, the canal and the Panama Canal Zone around it were managed by the United States. On September 7, 1977, U.S. President Jimmy Carter signed the Torrijos-Carter Treaty. This started the process of giving control of the canal to Panama. The treaty became active on October 2, 1979. It set up a 20-year period where Panama would take on more responsibility. The U.S. fully left on December 31, 1999. Since then, the canal has been managed by the Panama Canal Authority (ACP).

The transfer of the canal was strongly criticized by some groups in the U.S. But the treaty passed with enough votes in the Senate. Panamanians were happy to get control of the canal back. However, some people worried about possible negative economic effects at the time.

Even though there were concerns about the canal after the transfer, Panama has managed it well. According to ACP figures, canal income grew from $769 million in 2000 (the first year under Panamanian control) to $1.4 billion in 2006. Traffic through the canal increased from 230 million tons in 2000 to almost 300 million tons in 2006. The number of accidents has gone down. Travel time through the canal is about 30 hours, similar to the late 1990s. Canal expenses have increased less than revenue.

In 2006, the Panama Canal Authority suggested a plan to create a third lane of locks. This plan would use parts of old, unused approach canals from the 1940s. After a public vote, work began in 2007. The expanded canal started operating on June 26, 2016. The new locks allow larger ships, called Panamax ships, to pass through. These ships can carry more cargo than the original locks. The first ship to cross the canal through the new locks was a Chinese container ship. The expansion cost about $5.25 billion.

Former U.S. Ambassador to Panama, Linda Ellen Watt, said that Panama's operation of the canal has been "outstanding." She added, "The international shipping community is quite pleased."

See also

In Spanish: Historia del Canal de Panamá para niños

In Spanish: Historia del Canal de Panamá para niños

- Corozal "Silver" Cemetery – a cemetery near Panama City for workers on the Panama Canal.

- Latin America–United States relations

- Operation Pelikan

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |