History of the Nicaragua Canal facts for kids

Imagine a shortcut for ships across Central America! For a very long time, people have dreamed of building a canal through Nicaragua. This canal would connect the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, making sea travel much faster. The idea first came up hundreds of years ago, using the San Juan River to reach Lake Nicaragua. Even a famous leader, Napoléon III, wrote about how it could be done in the 1800s.

However, the United States decided to build the Panama Canal instead, which opened in 1914. This became the main shipping route. But as more and more ships travel the world, people still think a new canal in Nicaragua could be a good idea. In 2013, Nicaragua's government agreed to let a company from Hong Kong, called HKND Group, explore building and managing this huge project.

Contents

Where Would the Canal Go?

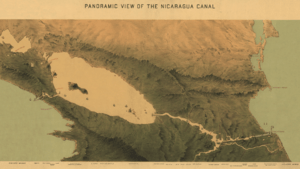

Many different paths have been suggested for the Nicaragua Canal, but they all use Lake Nicaragua. This lake is about 32 meters (105 feet) above sea level. Here are some of the main ideas for how ships could get from the Caribbean Sea to the lake:

- Route 1: From near Kukra Hill on the Caribbean coast, ships would go to the Escondido River and then to Lake Nicaragua.

- Route 2: From near Roca Caiman on the Caribbean coast, ships would also use the Escondido River to reach the lake.

- Route 3: Starting from the city of Bluefields on the Caribbean coast, this route also connects to the Escondido River and then to Lake Nicaragua.

- Routes 4 and 5: These paths would go from near Barra de Punta Gorda on the Caribbean coast directly to Lake Nicaragua.

- Route 6: This route follows the San Juan River from the town of San Juan de Nicaragua to Lake Nicaragua. This is similar to an older plan called the Ecocanal.

All these routes would lead ships from the Caribbean Sea to a town called Morrito on the eastern side of Lake Nicaragua. From there, ships would cross the lake to a town called La Virgen. Then, they would enter a man-made canal, traveling about 18–24 kilometers (11–15 miles) across a narrow strip of land called the isthmus of Rivas to reach the Pacific Ocean at a port called Brito.

Early Canal Ideas (1825–1909)

The idea of digging a waterway through Central America is very old! People thought about routes through Nicaragua, Panama, or Mexico. As early as 1551, a Spanish explorer named Gormara looked into it. Later, in 1781, the Spanish Crown tried again but couldn't find enough money.

In 1825, a new country called the Federal Republic of Central America (FRCA) became interested. They asked the United States for help with money and engineering. A study in the 1830s suggested a canal about 278 kilometers (173 miles) long, mostly following the San Juan River. It would need locks and tunnels to get from Lake Nicaragua to the Pacific.

Even though the U.S. government thought it was a good idea, the plan wasn't approved. The U.S. worried about Nicaragua's political problems and the interests of the British government, which controlled nearby areas.

First Agreements

In 1849, Nicaragua signed a deal with an American businessman named Cornelius Vanderbilt. His company, the Accessory Transit Company, got the right to build a canal within 12 years. They also ran a temporary route where people and goods crossed the Rivas land by train and stagecoach. This temporary route was very successful, connecting New York City and San Francisco. However, a civil war in Nicaragua and an invasion by an adventurer named William Walker stopped the canal from being built.

The idea of the canal remained important, leading to the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty in 1850 between the U.S. and Britain. In 1895, a Swiss geographer named Henri François Pittier warned that building the canal would be hard because of earthquakes and heavy rain in Nicaragua. He suggested studying the western part of the country, where there was less rain.

U.S. Canal Studies

In 1897, the United States Nicaraguan Canal Commission suggested building the canal. Another group, the Isthmian Canal Commission, also supported the idea in 1899. They even suggested buying the French work on the Panama Canal if it cost less than $40 million. Since the French project was having trouble, the U.S. bought it in 1902 for $40 million.

The Nicaraguan Canal Commission did a very detailed study of the San Juan River and its area. In 1899, they decided that a canal was possible and would cost about $138 million.

Why Panama Won Out

Before Nicaragua's proposal was ready, the U.S. Congress was already thinking about building the Panama Canal. People who didn't want the Nicaragua Canal pointed out the risk of volcanoes, especially Momotombo volcano. They preferred Panama.

In 1898, a man named Philippe Bunau Varilla, who owned land in Panama, hired William Nelson Cromwell to convince the U.S. Congress to choose Panama. In 1902, when there was more volcanic activity in the Caribbean, Cromwell spread a story in a newspaper saying that Momotombo volcano had erupted, causing earthquakes. This made people worry about a Nicaraguan canal.

Cromwell even sent leaflets with stamps showing Momotombo to every Senator as "proof" of volcanic activity in Nicaragua. When a volcano erupted on the island of Martinique in May 1902, killing 30,000 people, it convinced most of the U.S. Congress to vote for the Panama Canal. The decision to build the Panama Canal passed by just four votes. Cromwell was paid $800,000 for his efforts!

After this, Nicaragua's president, José Santos Zelaya, tried to get Germany and Japan to help build a canal. But since the U.S. had chosen Panama, they didn't support this idea.

After the Panama Canal Opened (1910–1989)

Even after the Panama Canal opened in 1914, the idea of a Nicaragua route was still considered. Building it would shorten the sea journey between New York and San Francisco by almost 800 kilometers (500 miles). In 1916, the Bryan–Chamorro Treaty was signed. The United States paid Nicaragua $3 million for the right to build a canal there forever, and also leased some islands and a naval base site.

In 1929, a detailed study for a new canal route was approved. From 1930 to 1931, a team of 300 U.S. Army engineers surveyed the route. They found that the proposed canal would be three times longer than the Panama Canal and cost twice as much. They also faced challenges like heavy rainfall and dangerous wildlife.

Costa Rica and El Salvador protested the Bryan–Chamorro Treaty, saying it affected their rights. The Central American Court of Justice agreed with them, but Nicaragua and the U.S. didn't accept the rulings. Both nations ended the treaty in 1970.

In the 1960s, there was even an idea to build a larger canal using atomic bombs for some of the digging, as part of something called Operation Plowshare.

New Interest (1990–2009)

In 1999, Nicaragua's government approved a plan to explore building a shallow waterway along the San Juan River, called the Ecocanal. This would connect Lake Nicaragua to the Caribbean Sea, but it wouldn't go all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

In 2000, another company was given permission to build a "dry canal" – a railway connecting Nicaragua's coasts. However, this company couldn't find the money to start building.

In 2004, the Nicaraguan government again proposed a canal big enough for huge ships, much larger than what the Panama Canal could handle. This project was estimated to cost as much as $25 billion, which is 25 times Nicaragua's yearly budget! Environmental groups strongly opposed it because of the potential damage to rivers and jungles.

In 2006, then-President Enrique Bolaños officially announced that Nicaragua planned to go ahead with the project. He believed there was enough demand for two canals in Central America. He said the project would cost about $18 billion and take about 12 years to build. It would greatly reduce travel time and costs for ships going from Europe to China and Japan.

Supporters believed that building the canal would more than double Nicaragua's economy and make it one of the wealthiest countries in Central America.

In 2009, Russian President Dimitry Medvedev showed interest in building the canal, but nothing came of it. The expansion of the Panama Canal likely reduced Russia's interest.

The HKND Project (2010–Present)

In 2010, Nicaragua signed a deal with two Korean companies to build a deepwater port on the Caribbean coast.

Then, in 2012, the Nicaraguan government asked for a study on the canal's feasibility. This study suggested that following the San Juan River would be cheaper and better for the environment.

On September 26, 2012, the Nicaraguan government signed an agreement with a new company called the Hong Kong Nicaragua Canal Development Group (HKND). This private company, led by billionaire Wang Jing, planned to finance and build the canal. They started studying how to build it, how much it would cost, and what its effects on the environment and local communities would be. The project was supposed to create many jobs for Nicaragua and other Central American countries.

On December 22, 2014, HKND announced that construction had begun in Rivas, Nicaragua. Wang Jing spoke at the starting ceremony. However, by 2016, not much had actually been built. Major work like digging was supposed to start after a Pacific Ocean dock was finished, but that dock's construction was delayed.

In April 2016, a newspaper reported that the project seemed stuck. Nicaragua's president hadn't mentioned the canal in months, and cows were still grazing where Wang had held his groundbreaking ceremony. Wang Jing himself had faced financial problems, losing a lot of his wealth.

By April 2018, Wang Jing had closed the HKND headquarters in China, and the company seemed to have disappeared. Even though HKND vanished, the Nicaraguan government still says it will continue with plans to take over a huge amount of land (908 square kilometers or 350 square miles) under a law passed in 2013. This law allows for seven related projects, like ports, oil pipelines, and tourist areas. People have called this a "land grab" because the law doesn't allow appeals against the land seizure and offers very little payment. This has led to protests and some conflicts.

Activists point out that the canal contract stated it should be canceled if the company didn't get the money to start the project within 72 months. That deadline was June 14, 2019, so they believe the land expropriation law should be canceled too.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |