Panama Canal expansion project facts for kids

The Panama Canal expansion project (Spanish: ampliación del Canal de Panamá), also known as the Third Set of Locks Project, made the Panama Canal much bigger. It added a new lane for ships, allowing more vessels to pass through. It also made the lanes and locks wider and deeper. This meant much larger ships, called New Panamax vessels, could use the canal. These new ships are about one and a half times bigger than the older Panamax size and can carry more than twice as much cargo. The expanded canal started working for ships on June 26, 2016.

The project involved:

- Building two new sets of locks, one on the Atlantic side and one on the Pacific side.

- Digging new channels to connect to these new locks.

- Making existing channels wider and deeper.

- Raising the water level of Gatun Lake slightly.

The President of Panama at the time, Martín Torrijos, suggested the project on April 24, 2006. He said it would help Panama become a more developed country. People in Panama voted on the idea in a special election on October 22, 2006, and 76.8 percent said yes! The project officially began in 2007.

It was first planned to finish the expansion by August 2014, which would have been the 100th anniversary of the Panama Canal opening. However, there were some delays, like worker strikes and disagreements with the construction companies about extra costs. These issues pushed the completion date back several times. After a few more challenges, including some water leaks from the new locks, the expanded canal finally opened on June 26, 2016. This expansion doubled the canal's capacity. By March 2, 2018, the Panama Canal Authority announced that 3,000 New Panamax ships had already used the new canal lanes in its first 20 months.

Contents

Why the Canal Needed to Grow

The original Panama Canal had limits on how many ships could pass through. This was because of how long it took to operate the existing locks. Also, ships were getting bigger, closer to the maximum Panamax size, which took even more time to move through the locks and channels. Sometimes, the canal also needed to close for maintenance because it was getting old.

More and more goods were being shipped around the world, so demand for the canal was growing. The Panama Canal Authority (ACP), which manages the canal, thought the canal would reach its busiest point between 2009 and 2012. The best long-term solution for this busy traffic was to expand the canal with a third set of locks.

Ship Sizes and New Locks

The size of ships that could use the original canal was called Panamax. These ships were limited by the size of the locks, which were about 33.5 meters (110 feet) wide and 320 meters (1,050 feet) long, and 12.5 meters (41.2 feet) deep. The new third set of locks allows much larger ships, called Post-Panamax ships, to pass through. These ships can carry more cargo than the old locks could handle. The new lock chambers are about 55 meters (180 feet) wide, 427 meters (1,400 feet) long, and 18.3 meters (60 feet) deep. These new sizes mean that about 79% of all cargo ships in the world can now use the canal, up from only 45% before the expansion.

Studies since the 1930s always showed that building a third, larger set of locks was the best way to increase the canal's capacity. The United States even started digging for new locks in 1939 but stopped in 1942 because of World War II. The Panama Canal Authority's plans for 2025 also confirmed that a third, larger set of locks was the best choice for the canal's future.

President Martín Torrijos explained the project by saying the canal "is like our 'petroleum'." He meant that just like oil needs to be taken out of the ground to be useful, the canal needed to expand to handle more cargo and bring more wealth to Panama.

While the expansion was being built, and because ships sometimes had to wait a long time (up to seven days during busy seasons), the ACP created a special system. Ships could pay an extra fee to book a specific time to cross the canal, guaranteeing they would pass in 18 hours or less. This helped manage the busy traffic and offered better service to shipping companies.

How Much Cargo Moves Through

The Panama Canal Authority expected the amount of cargo moving through the canal to grow by about 3% each year. This meant the total amount of goods would double by 2025 compared to 2005. Allowing bigger ships to pass means more cargo can move with each trip, using less water per ton of goods.

Historically, the canal made most of its money from dry goods (like grains, minerals, coal) and liquid goods (like chemicals, oil). More recently, goods packed in containers became the main source of income, pushing dry goods to second place. Vehicle carriers (ships that carry cars) became the third biggest income source. Experts believe the canal expansion will be good for both the canal and its users because it can handle more goods.

Much of the recent growth in canal use came from US imports from China, which passed through the canal to ports on the US East and Gulf coasts. However, some critics, like former canal administrator Fernando Manfredo, questioned if this growth would continue for many years. They argued it was risky for Panama to rely so much on such long-term predictions.

Who the Canal Competes With

The Panama Canal has competitors. These are other ways to transport cargo between the same places.

One possible future competitor is the Northern Sea Route in Russia and the Canadian Northwest Passage. These routes through the Arctic Ocean could open up more often as the climate changes. However, they would need a lot of investment in special ships and ports. Experts in Canada don't think these routes will be a real alternative to the Panama Canal for another 10 to 20 years.

The two main current competitors are the US intermodal system (which uses different types of transport like ships, trains, and trucks) and the Suez Canal in Egypt. Ports and distribution centers along these routes are investing in their facilities to handle large Post-Panamax container ships. The ACP believed that more and more of these huge ships would be used on routes that compete with Panama.

The expansion aimed to make the canal stronger against this competition. By being able to handle more demand, Panama could become a very important connection point for trade between continents. This would help the canal stay important and continue to help Panama's economy grow.

What Was Predicted

Studies by the ACP in 2005 predicted that the canal would reach its maximum capacity between 2009 and 2012. If it couldn't handle more demand, it would become less competitive.

The expansion project was approved by the people of Panama and was expected to finish by April 2016. The ACP said it would do everything possible to handle traffic until the new locks were ready.

The expanded canal, with its new third set of locks, was designed to handle all the expected demand for shipping through 2025 and beyond. Together, the old and new locks roughly doubled the canal's capacity.

Some critics, like former politician Keith Holder, pointed out that canal use changes with the seasons. They argued that even when it was busiest, the real slowdown wasn't the locks, but the narrow Culebra Cut, where it was hard for large ships to pass each other.

Even though the canal was getting close to its maximum capacity, it didn't mean ships couldn't pass. It just meant the canal couldn't grow and take on more cargo.

The Expansion Project Details

New Locks and How They Work

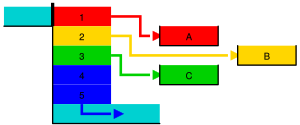

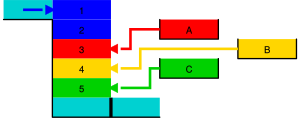

The original canal has two lanes, each with its own set of locks. The expansion project added a third lane by building new lock complexes at each end of the canal. One new lock complex is on the Pacific side, and the other is on the Atlantic side. Each of these new lock complexes has three chambers in a row. These chambers lift ships from sea level up to the level of Gatun Lake and then lower them back down.

Each chamber has three special basins next to it that save water. This means there are nine basins per lock complex, making 18 basins in total. Just like the original locks, the new locks and their basins fill and empty using only gravity, without needing any pumps. The new locks were built in an area that the United States started digging in 1939 but stopped during World War II. The new locks are connected to the existing canal system by new shipping channels. The new lock chambers are about 427 meters (1,400 feet) long, 55 meters (180 feet) wide, and 18.3 meters (60 feet) deep. They use rolling gates instead of the swinging gates found in the old locks. Rolling gates are common in other large locks and are a proven technology. The new locks use tugboats to guide ships, instead of the electric locomotives (mules) used in the old locks. Tugboats are also widely used for this purpose in similar large locks.

Water-Saving Basins

The new locks have water-saving basins to use less water during operation. Both the old and new locks work using gravity and valves, with no pumps.

All locks use water from Gatun Lake. During Panama's dry season, the lake's water level can get low. Adding a third set of locks meant this water supply issue needed to be addressed.

For the new locks, three basins are connected to each lock chamber. This design allows about three-fifths of the water to be reused, meaning only two-fifths of the water is "lost" per cycle.

Here's how the water-saving basins work: Imagine the water in a lock chamber is divided into five equal "slices." When the canal first starts, the chamber is filled once from Gatun Lake. Then, when emptying the chamber, the top three slices of water are emptied, one by one, into the three basins next to the lock. Each basin is at a slightly lower level. The last two slices of water are emptied into the next lock chamber and are "lost" (like in the original canal locks).

When a ship moves upward, the chamber is closed. Water from the basins is first let back into the chamber, filling the bottom three slices. Then, the top two slices are filled from Gatun Lake. This means only two-fifths of the water needed to fill the chamber comes directly from Gatun Lake, saving a lot of water.

New Channels for Ships

The plan included digging a new access channel about 3.2 kilometers (2 miles) long to connect the new Atlantic locks to the existing sea entrance of the canal. On the Pacific side, two new access channels were built:

- A 6.2-kilometer (3.9-mile) north access channel connects the new Pacific-side lock to the Culebra Cut. This channel goes around Miraflores Lake.

- A 1.8-kilometer (1.1-mile) south access channel connects the new lock to the Pacific Ocean entrance.

These new channels on both the Atlantic and Pacific sides are at least 218 meters (715 feet) wide. This allows Post-Panamax ships to travel in one direction at a time.

Gatun Lake's Higher Water Level

The maximum operating water level of Gatun Lake was raised slightly, by about 0.45 meters (1.5 feet). This, along with widening and deepening the channels, increased the lake's usable water storage. This extra water means the canal can provide about 165 million US gallons (625,000 cubic meters) of additional water daily. This is enough to allow about 1,100 more lockages each year without affecting the water supply for people, which also comes from Gatun and Alhajuela Lakes.

Building the Expansion

The construction of the third set of locks was originally planned to take seven or eight years. The new locks were expected to start working between 2014 and 2015, around 100 years after the canal first opened. However, in July 2012, it was announced that the project was six months behind schedule, pushing the opening to April 2015. By September 2014, the new gates were expected to open in early 2016.

In October 2011, the Panama Canal Authority announced that the third phase of digging for the Pacific access channel was finished.

In June 2012, a huge concrete block, 30.5 meters (100 feet) tall, was completed. This was the first of 46 such blocks that form the walls of the new Pacific-side locks.

Sixteen new lock gates were installed: eight on the Atlantic side and eight on the Pacific side. The installation started in December 2014 with a 3,285-ton gate on the Atlantic side. It finished in April 2015 with a 4,232-ton gate on the Pacific side.

In June 2015, the new locks began to be filled with water, first on the Atlantic side, then on the Pacific. By then, the canal's re-opening was set for April 2016.

In August 2015, a crack was reported in a concrete part of the new Cocolí locks. At first, it wasn't expected to delay the project. However, by November 2015, cracks found over several months threatened to cause delays. Repairs to strengthen the sills were expected to be done by January 2016. In early February 2016, the ACP confirmed that the repairs were complete.

By January 2016, Panama's President Varela thought the expansion would be finished around May 2016.

The expanded canal officially began commercial operation on June 26, 2016. The first ship to cross using the new locks was a modern New Panamax vessel, the Chinese-owned container ship "Cosco Shipping Panama."

Money Matters

The main goal of the canal expansion was to help Panama earn more money from the increasing demand for shipping. This demand came from both more cargo and bigger ships wanting to use the Panama route. With the third set of locks, the canal could handle the expected shipping traffic beyond 2025. Total earnings for that year were predicted to be over US$6.2 billion.

How Much It Cost

In 2006, the ACP estimated the project would cost US$5.25 billion. This amount included everything: design, management, construction, testing, environmental protection, and starting up the new locks. It also included money for unexpected problems like accidents, design changes, price increases, and delays. The cost of interest paid on loans during construction was not included. The biggest costs were for building the two new lock complexes, one on each side, which were estimated at US$1.11 billion and US$1.03 billion, plus extra money for unexpected issues during their construction.

Some people who were against the project argued that the cost estimates were based on uncertain predictions about world trade and the economy. They also claimed the project would cost much more than planned and was too risky for Panama.

How It Was Paid For

The ACP believed the third set of locks would make money, earning a 12 percent return on investment. The project's funding was separate from the government's regular budget. The government did not guarantee any loans taken by the ACP for the project. The ACP expected to borrow about US$2.3 billion temporarily to cover the busiest construction times between 2009 and 2011.

The ACP's predictions for earnings were based on assumptions about more ships using the canal and companies being willing to pay higher fees. To attract new business and keep current customers, the ACP planned to offer financial incentives, like a loyalty program. With the money earned from the expanded canal, the costs were expected to be paid back in less than 10 years, and the loans could be repaid in about eight years.

A US$2.3 billion funding package for the expansion was signed in December 2008. It included loans from several government-owned financial institutions:

- Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) – US$800 million

- European Investment Bank (EIB) – US$500 million

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) – US$400 million

- CAF – Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean (CAF) – US$300 million

- International Finance Corporation (IFC) – US$300 million

These loans were for 20 years, with a 10-year grace period (meaning no payments were due for the first 10 years).

Impact on the Environment

The ACP stated that the project would not cause lasting harm to the environment, communities, forests, national parks, historical sites, farms, factories, or tourist areas. They said any harm could be fixed using existing methods and technology.

The proposal also claimed the project would not permanently lower water or air quality. The plan for water supply was designed to use water from Gatun and Alhajuela Lakes efficiently. This meant no new reservoirs would be needed, and no communities would have to move.

However, some critics worried about environmental issues, such as how the project might affect water supplies, especially during dry periods linked to El Niño. The ACP did order studies about water supply and quality problems.

Some critics argued that the ACP's public statements didn't always match what their studies found. They claimed that some studies suggested the new water-saving basins could allow more salt water into Gatun Lake. This is important because about half of Panama's population gets its drinking water from Gatun Lake. The ACP said this problem could be reduced by flushing the new locks with fresh water from Gatun Lake, but critics pointed out this would defeat the purpose of saving water.

On the other hand, one of Panama's main environmental groups, the National Association for Nature Conservation (ANCON), said that the studies showed very low levels of salt in Gatun Lake's water. They believed these levels would protect the natural separation of the oceans and keep the water safe for people and wildlife.

Jobs Created

The ACP said the canal expansion would first create jobs directly from its construction. About 35,000–40,000 new jobs were created during the building of the third set of locks. This included 6,500–7,000 direct jobs during the busiest construction years. However, officials said the most important job impacts would be in the medium and long term. These would come from the economic growth caused by the extra money the expanded canal brought in and the increased shipping activity.

Most of the construction work for the third set of locks was done by Panamanians. To make sure there were enough skilled workers, the ACP and other groups worked together to train the necessary workforce. The costs for these training programs were included in the project's budget.

Some critics disagreed, saying that the ACP's own studies showed fewer than 6,000 jobs would be created at the peak of construction. They also argued that some highly skilled jobs would be filled by foreign workers because not enough Panamanians were qualified.

Panama's construction workers' union, SUNTRACS, was among those who opposed the expansion. Workers went on strike asking for higher pay and better safety. The union's leader, Genaro Lopez, argued that while some construction jobs would be created, the debt Panama took on to build the locks would mean less canal money would go to the government for things like roads, schools, and police.

Critics also felt the project didn't have a good plan for social development. The President at the time, Torrijos, later agreed to work with the United Nations Development Programme to create one.

Who Supported the Project

The National Association for Nature Conservation (ANCON) approved the environmental studies and offered some suggestions before the project was approved. Other supporters included:

- The La Prensa newspaper

- The Chamber of Commerce, Industries and Agriculture

- The CONATO (National Council of Organized Workers)

- Stanley Heckadon, a former director of an environmental agency

- Famous Panamanians like former Miss Universe Justine Pasek, writer Rosa María Britton, and painter Olga Sinclair

- Many canal customers and businesses in the shipping industry

- 77% of Panamanian voters in a referendum, though only 43% of voters participated.

Who Was Against the Project

Some people, like former President Jorge Illueca and former Panama Canal Commission official Fernando Manfredo, believed the expansion wasn't needed. They thought building a very large port on the Pacific side would be enough to handle future shipping demand. Such a port would be the second in the American Pacific deep enough for Post-Panamax ships (the first being Los Angeles). They argued that Panama could then move containers from the Pacific to the Atlantic side by train, where they would be loaded onto other ships.

Other groups and people who opposed the project included:

- The Council on Hemispheric Affairs (COHA), which said the expansion might not help most Panamanians. They worried that many benefits would go to businesses and their partners in the US, and that corruption in Panama raised questions about managing such a huge project.

- Former President Guillermo Endara and his political party, Vanguardia Moral de la Patria.

- Most of the left-wing groups and labor unions in Panama, including CONUSI and Frenadeso.

- Most members of the nationalist Panameñista Party.

See also

In Spanish: Ampliación del canal de Panamá para niños

In Spanish: Ampliación del canal de Panamá para niños

- Bayonne Bridge, an American bridge raised to accommodate post-Panamax ships

- Nicaragua Canal

- Tehuantepec Route

- Megaproject

- Panama Canal Railway

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |