Carl Akeley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Carl Akeley

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | May 19, 1864 |

| Died | November 17, 1926 (aged 62) Mt. Mikeno, Belgian Congo

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Awards | John Scott Medal (1916) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Taxidermy |

| Institutions | Milwaukee Public Museum, Field Museum of Natural History, American Museum of Natural History, the Smithsonian Institution |

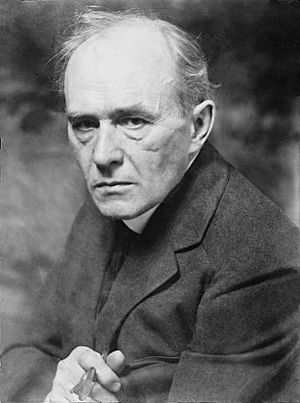

Carl Ethan Akeley (May 19, 1864 – November 17, 1926) was an amazing American expert in many fields. He was a taxidermist, sculptor, biologist, conservationist, inventor, and nature photographer. He made huge contributions to American museums, especially the Milwaukee Public Museum, Field Museum of Natural History, and the American Museum of Natural History.

Many people call him the "father of modern taxidermy." He also started the AMNH Exhibitions Lab. This special department combines scientific research with creating exciting museum exhibits.

Template:TOC limit=3

Contents

Carl Akeley's Life and Work

Carl Akeley was born in Clarendon, New York. He grew up on a farm and only went to school for three years. He learned how to do taxidermy from David Bruce. Later, he became an apprentice at Ward's Natural Science Establishment. While there, Akeley even helped prepare P.T. Barnum's famous elephant, Jumbo, after it died.

In 1886, Akeley started working at the Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM). He stayed in Milwaukee for six years, making his taxidermy methods much better. At the MPM, he worked on animals found in Wisconsin. One of his early works was a diorama of a muskrat group. A diorama is a scene that shows animals in their natural home. He also created exhibits of reindeer and orangutans.

Innovations in Taxidermy

Akeley left the Milwaukee Public Museum in 1892. He then opened his own studio. In 1896, he joined the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. There, he developed new ways to prepare animals for display. He created light, hollow, but strong models, called mannequins. He would then put the animal's skin over these models.

His methods were special because he sculpted the animal's muscles first. This made the animals look very real and alive, often in active poses. Akeley was the Field Museum's main taxidermist from 1896 to 1909. He prepared over 130 mounted animals and dioramas. His most famous work is the "Fighting African Elephants" exhibit. He and his first wife, Delia Akeley, collected these elephants in Africa.

Akeley's Inventions

Carl Akeley was also a great inventor. He created a "cement gun" to fix the outside of the Field Columbian Museum. This invention is now known as shotcrete or "gunite." It's a type of concrete that can be sprayed.

Akeley also invented a special movie camera for filming wildlife. This camera was very easy to move around. He even started a company to make it and got a patent for it in 1915. The Akeley "pancake" camera was used by the military in World War I. It was also used by news companies and Hollywood studios for action scenes. Akeley wrote several books, including stories for children. He also wrote an autobiography called In Brightest Africa. He received more than 30 patents for his inventions.

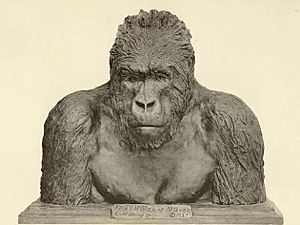

Akeley focused on African mammals, especially gorillas and elephants. He made taxidermy much better by carefully fitting the skin over a sculpted form. This made the animals look very lifelike, showing their muscles, wrinkles, and even veins. He also displayed animals in groups in their natural settings. Many of the animals he preserved were ones he had personally collected.

The Akeley Method

Carl Akeley strongly believed that taxidermy could make mounted animals look not just lifelike, but truly alive. He also wanted to show animals in their correct natural homes and how they interacted with each other.

Akeley's methods created very accurate, skinless models of animals. These models showed the animal in lifelike actions and poses. The models were very light and hollow. They were mostly made of papier mache and wire mesh. Akeley based his models on exact measurements and photos taken in the wild. He also used his deep knowledge of the animal's body and behavior. After making the model, the animal's hide and hooves were carefully attached.

Here are the steps to the Akeley Method:

- Akeley first made a small, detailed clay model of the animal.

- Then, he built a frame using bones, wood, metal rods, and wire mesh.

- He covered this frame with plaster and then clay. He sculpted the clay to make an exact model of the living animal.

- Next, he covered the clay model with plaster. When it dried, the plaster mold was removed in pieces. This created a perfect mold of his sculpted model.

- Papier mache pulp and wire mesh were put inside the plaster mold. When this dried, it made a full-size, hollow model. This model was the exact shape of his original sculpture.

- Finally, the animal's original skin was put over the model and sewn up. This way, no seams could be seen.

African Expeditions

Akeley first traveled to Africa in 1896. He was invited by Daniel Elliot from the new Columbian Field Museum. This trip to Somaliland lasted eight months. Akeley collected many animal specimens, including hartebeest, gazelles, hyenas, kudus, oryx, and lions.

In 1905, Marshall Field paid for Akeley's next trip to Africa. This trip lasted a year. Akeley brought back two male elephants that he would later prepare for display. He took nearly 1,000 glass plate photos. He also collected 17 tons of materials. This included 400 large mammal skins, 1200 small mammal skins, and 800 bird skins. He also collected many bird and mammal skeletons. Besides animal materials, he collected over 900 items related to human culture. He also brought back crates of leaves to use as models for his dioramas.

In 1909, Akeley joined Theodore Roosevelt on a year-long trip to Africa. This trip was paid for by the Smithsonian Institution. Akeley then started working at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. You can still see his work in the Akeley Hall of African Mammals there.

In 1921, Akeley led a trip to Mt. Mikeno in the Virunga Mountains. He wanted to learn about gorillas to decide if collecting them for museums was right. At that time, gorillas were very rare in zoos. Collecting such animals for educational exhibits was common. While collecting several mountain gorillas, Akeley's feelings changed. For the rest of his life, he worked to create a gorilla preserve in the Virungas.

In 1925, King Albert I of Belgium was greatly influenced by Akeley. He created the Albert National Park, which is now called Virunga National Park. It was Africa's first national park. Akeley was against hunting gorillas for sport. But he still believed in collecting them for science and education.

Akeley began his fifth trip to the Congo in late 1926. He died on November 18 from a sickness called dysentery. He was buried in Africa, close to where he first saw a gorilla, known as the "Old Man of Mikeno."

Personal Life

Carl Akeley's second wife, Mary Jobe Akeley, married him two years before he died. Before that, he was married to Delia J. Akeley for almost 20 years. Delia Akeley went with him on two of his biggest trips to Africa in 1905 and 1909. Delia later returned to Africa twice on her own. She lived for several months with the Pygmies in the Ituri Forest.

Legacy

The World Taxidermy & Fish Carving Championships give out gold medals that show Carl Akeley's face. These are given to the "Best in World" winners. There is also a Carl Akeley Award for the most artistic animal display at the World Show.

The Akeley Hall of African Mammals at the American Museum of Natural History is named after him. So is the Akeley Memorial Hall at The Field Museum.

See also

In Spanish: Carl Akeley para niños

In Spanish: Carl Akeley para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |