George Hunt (ethnologist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

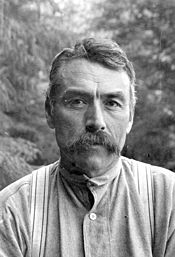

George Hunt

|

|

|---|---|

George Hunt in 1898

|

|

| Born | February 14, 1854 |

| Died | 1933 |

| Occupation | Ethnologist, Linguist, Artist |

| Parent(s) | Robert Hunt, Mary Ebbetts (Anislaga) |

George Hunt (born February 14, 1854 – died 1933) was a Canadian from the Tlingit people. He worked closely with Franz Boas, an American anthropologist. Because of his important work, many people see him as a linguist (someone who studies languages) and an ethnologist (someone who studies cultures).

George Hunt was born to a Tlingit mother and an English father. He learned both of their languages. He grew up in Fort Rupert, British Columbia, which is in Kwakwaka'wakw territory. There, he also learned the Kwakwaka'wakw language and their culture. Through marriage and adoption, he became an expert on the traditions of the Kwakwaka'wakw people. At that time, they were often called "Kwakiutl."

Working with Franz Boas, Hunt gathered hundreds of items for an exhibit. This exhibit showed the Kwakiutl culture at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. He also traveled to Chicago with 17 people from the tribe. Boas taught Hunt how to write in the Kwak'wala language. Over many years, Hunt wrote thousands of pages describing Kwakwaka'wakw culture.

Contents

George Hunt's Early Life and Learning

George Hunt was born in 1854 in Fort Rupert, British Columbia. He was the second of eleven children. His father, Robert Hunt (1828-1893), was a fur trader from England. He worked for the Hudson's Bay Company.

George's mother was Mary Ebbetts (1823-1919). She was a member of the Raven clan of the Taantakwáan tribe. This tribe is part of the Tlingit nation in what is now southeastern Alaska. Mary's father was Chief Keishíshk' Shakes IV.

Robert and Mary were married at Lax Kw'alaams, which was then called Fort Simpson. This place is near the Nass River in northwestern British Columbia.

Mary Ebbetts' Influence

Mary Hunt, George's mother, was a skilled Chilkat weaver. She was very important among the Kwakwaka'wakw people at Fort Rupert. She brought ideas about Tlingit family rights and art styles into the local society. You can see these styles on totem poles.

George learned his mother's Tlingit language and culture. He also learned English and parts of his father's culture. He learned the Kwakwaka'wakw language and about the local area from the Kwakwaka'wakw people. Because of this, he became a good interpreter and guide.

His reputation grew over time. In the early 1880s, Hunt worked as a boatman, guide, and interpreter. He helped Bernard Fillip Jacobsen, an explorer and ethnologist. Jacobsen was part of the large Jesup North Pacific Expedition. George Hunt might have first met Franz Boas, the main organizer of this expedition, around this time.

George Hunt's Work as an Ethnologist

George Hunt's long partnership with Franz Boas began in 1886. Boas, an American anthropologist, first visited the Kwakwaka'wakw people as part of the Jesup Expedition. Hunt worked as his interpreter. He helped Boas understand the culture and its practices.

They continued to work together for many years. Boas later taught Hunt how to write the Kwak'wala language. This allowed Hunt to record oral histories and other cultural information. Boas even named Hunt as a co-author in one of his books, Kwakiutl Texts, second series (1906). This was one of many books published about the Jesup expedition's work.

The 1893 World's Fair Exhibit

Boas and Hunt worked together to create an exhibit for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. This exhibit showed the Kwakiutl and other Native American cultures from the Pacific Northwest. Hunt collected hundreds of items for the fair. These included a house and several carved poles.

In April 1893, Hunt traveled to Chicago with 17 Kwakiutl people from Fort Rupert, British Columbia. They built a village on the fairgrounds. The Kwakiutl people lived there during the fair. They showed their ceremonial dances, arts, and other traditions. For the performers, it was a chance to do songs and dances that had been banned by Canadian government officials. After the Exposition, most of the items from the exhibit were given to the Field Museum. Many of them are still on display there today.

Hunt was also important in the purchase of the Yuquot Whalers' Shrine in 1904. This object has caused some debate in recent years. The Yuquot people have tried to get this work back.

Over the years, Hunt wrote about ten thousand pages of cultural descriptions for Boas. This work covered all parts of Kwakwaka'wakw culture. This included potlatch ceremonies, which Hunt took part in. When Boas received texts from other speakers, he sent them to Hunt to check. In a letter from 1931, Boas said, "In some cases, I can guess what is wrong but I had rather have you correct it than use my own uncertain knowledge of Kwakiutl."

George Hunt's Lasting Impact

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, wealthy people started collecting art from the Pacific Northwest Indigenous peoples, including totem poles. James L. Kraft, who started Kraft Inc., gave a Kwakiutl totem pole to the city of Chicago. It was put in a park by the water in 1929. The pole was forty feet tall and carved from a single cedar tree in the traditional way.

After many years, the pole started to wear out. Kraft, Inc. asked for a new one to be made. The original pole was sent to British Columbia in 1985 for study and to be preserved. Its history and art value were very high.

George Hunt's descendant, Tony Hunt Sr., is a Kwakwaka'wakw hereditary chief and artist. In 1986, he carved a new totem pole called Kwanusila. It looked just like the original pole, with the same design and colors. It was put in the park by the lake.

Hunt's work can also be seen in other places. These include the Saint Louis Art Museum, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History. Some of his work is also owned by private collectors.

Hunt Family Artists

George Hunt's family also includes Dr. Gloria Cranmer Webster and the filmmaker Barbara Cranmer. Many artists in the Hunt family continue the tradition of Northwest Coast art. These include Henry Hunt, and his sons Tony, Stanley C. Hunt, and Richard Hunt. Their second cousin, Calvin Hunt, and Corrine Hunt are also artists. Corrine Hunt designed all the gold, silver, and bronze medals for the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics and Paralympic games.

In 1986, members of the Boas and Hunt families had a "reunion" at Tsaxis (Fort Rupert). In 1995, the Hunt family hosted a potlatch. This was to celebrate the Long House: Kwakwaka'wakw Big House House of the Chiefs Kanada, Turtle Island. This celebration was also in Tsaxis, Fort Rupert. Master carver Tony Hunt Sr. led the Gudzi Community Big House project. The late Henry Hunt Sr. shared his skills. He oversaw the carving of the three Sisiutl Heads and Frogs on Tongues. Tony Hunt Jr., Tommy Hunt Jr., Steven Hunt, and George Jr. Hunt carved the Double-Headed Serpent and Frogs on Tongues with their Uncle Henry Hunt Sr.

Images for kids

-

House frontal totem pole carved by George Hunt, for the 1914 motion picture, In the Land of the War Canoes, directed by Edward Curtis. UBC Museum of Anthropology.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |