Franz Boas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Franz Boas

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Franz Uri Boas

July 9, 1858 Minden, Prussia, German Confederation

|

| Died | December 21, 1942 (aged 84) New York City, New York, U.S.

|

| Citizenship | Germany United States |

| Alma mater |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Marie Krackowizer Boas

(m. 1887) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions |

|

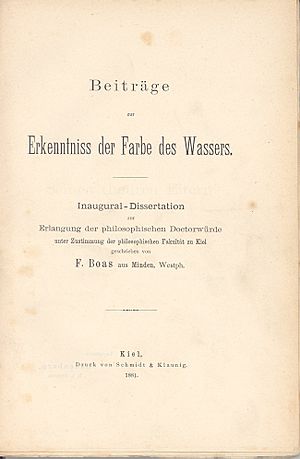

| Thesis | Beiträge zur Erkenntniss der Farbe des Wassers (1881) |

| Doctoral advisor | Gustav Karsten |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Other notable students |

|

| Influences |

|

| Influenced |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

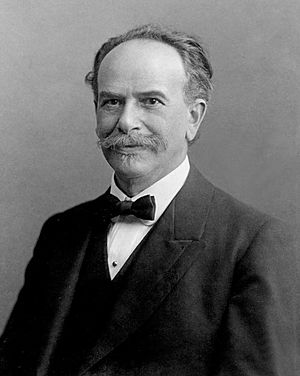

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist. He is often called the "Father of American Anthropology". He helped create modern anthropology. His ideas include historical particularism and cultural relativism.

Boas studied in Germany and earned a PhD in physics in 1881. He also studied geography. Later, he joined a trip to northern Canada. There, he became very interested in the culture and language of the Baffin Island Inuit people. He then did more fieldwork with native groups in the Pacific Northwest.

In 1887, he moved to the United States. He first worked at the Smithsonian museum. In 1899, he became an anthropology professor at Columbia University. He stayed there for the rest of his career. Many of his students became important anthropologists. They started new anthropology departments and research programs. Boas greatly shaped how American anthropology grew. Some famous students were A. L. Kroeber, Ruth Benedict, Edward Sapir, Margaret Mead, and Zora Neale Hurston.

Boas strongly disagreed with scientific racism. This was a popular idea that said human races were biological and that behavior came from biology. Boas did studies on bones and skulls. He showed that head shape and size could change based on things like health and food. This was different from what other scientists said. They thought head shape was a fixed racial trait. Boas also showed that differences in human behavior come from culture, not just biology. He taught that people learn behaviors from their society. Because of this, Boas made "culture" a main idea for understanding human groups in anthropology.

One of Boas's biggest ideas was rejecting old ways of studying culture. These old ideas said all societies moved through the same stages, with Western Europe at the top. Boas argued that cultures grew through people interacting and sharing ideas. He believed there was no single path to "higher" cultures. This idea made him change how museums showed items. Instead of showing items by "stage," he grouped them by how close and similar the cultures were.

Boas also brought in the idea of cultural relativism. This means that no culture is truly "higher" or "better" than another. All humans see the world through their own culture's viewpoint. They judge things based on their own cultural rules. Boas believed anthropology's goal was to understand how culture shapes how people see and act in the world. To do this, he said it was important to learn the language and practices of the people being studied.

Boas combined different areas of study:

- Archaeology: studying old objects and history.

- Physical anthropology: studying human body differences.

- Ethnology: studying cultural differences and customs.

- Descriptive linguistics: studying unwritten native languages.

This led to the four-field approach in anthropology. This approach became very important in American anthropology in the 20th century.

Contents

His Early Life and Studies

Franz Boas was born on July 9, 1858, in Minden, Germany. His parents, Sophie Meyer and Meier Boas, were educated and open-minded. They valued new ideas from the Age of Enlightenment. They did not like strict rules or beliefs. An important person in his early life was his uncle, Abraham Jacobi. He was a friend of Karl Marx and helped guide Boas's career. This helped Boas think for himself and follow his own interests. From a young age, he loved nature and science. Boas spoke out against antisemitism (hatred of Jewish people). He refused to become a Christian, but he did not strongly identify as Jewish.

From kindergarten on, Boas learned about natural history, which he enjoyed. In high school (called Gymnasium), he was proud of his research on where plants grew.

For college, Boas first went to Heidelberg University. Then he spent four terms at Bonn University. He studied physics, geography, and mathematics. In 1879, he wanted to study physics in Berlin. But he moved to the University of Kiel instead for family reasons. At Kiel, Boas wanted to study a math topic for his main paper (dissertation). But his advisor, physicist Gustav Karsten, chose a topic for him: the way water reflects light. Boas finished his paper, "Contributions to the Perception of the Color of Water," in 1881. He earned his PhD in physics.

While at Bonn, Boas took geography classes from Theobald Fischer. They became friends. Fischer was a student of Carl Ritter and made Boas interested in geography again. Fischer had a bigger impact on Boas than Karsten did. Some people even think of Boas as more of a geographer at this time. Boas also defended six smaller papers. One was likely in geography, as Fischer was one of his examiners. By the time he finished his PhD, Boas saw himself as a geographer.

In his research, Boas studied how different light made water look different colors. He found it hard to see small differences in water color. This made him curious about how people see things and how it affects measurements. Boas later had trouble studying tonal languages because he was tone deaf. These experiences made Boas think about studying psychophysics. This field looks at how the mind and body are connected. He published six articles on psychophysics during his military service (1882–1883). But he decided to focus on geography to get funding for his trip to Baffin Island.

Exploring New Cultures

Boas chose geography to explore how what we experience connects to the real world. German geographers at the time disagreed on why cultures were different. Some thought the environment was the main reason. Others, like Friedrich Ratzel, believed that ideas spreading through human movement were more important. In 1883, Boas went to Baffin Island. He wanted to study how the environment affected Inuit movements. This was his first of many trips to study different cultures. He used his notes to write his first book, The Central Eskimo, published in 1888. Boas lived and worked closely with the Inuit. He became deeply interested in their way of life.

During the dark Arctic winter, Boas and his travel partner got lost. They had to sled for 26 hours through ice and snow in very cold temperatures. Boas wrote that "all service, therefore, which a man can perform for humanity must serve to promote truth." He relied on different Inuit groups for directions, food, shelter, and company. It was a tough year with many challenges, including sickness and danger. Boas found new areas and unique cultural items. The long winter made him think deeply about his life as a scientist.

Boas's interest in native groups grew when he worked at the Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin. There, he met members of the Nuxalk Nation from British Columbia. This started a lifelong connection with the First Nations of the Pacific Northwest.

He went back to Berlin to finish his studies. In 1886, Boas defended his main paper, Baffin Land. He became a private lecturer in geography.

While on Baffin Island, he started to study non-Western cultures. This led to his book, The Central Eskimo, in 1888. In 1885, Boas worked with physical anthropologist Rudolf Virchow and ethnologist Adolf Bastian in Berlin. Boas had studied anatomy with Virchow earlier. Virchow was debating evolution with his former student, Ernst Haeckel. Haeckel strongly supported Charles Darwin's ideas in Germany. But Virchow, like many scientists then, felt Darwin's ideas were weak without a theory of cell change. So, Virchow preferred ideas like Lamarck's evolution. This debate was similar to those among geographers.

Boas worked more closely with Bastian. Bastian did not like the idea that the environment decided everything. He believed in "psychic unity of mankind." This meant all humans had the same thinking ability. All cultures were based on the same basic mental rules. He argued that differences in customs came from historical events. This idea fit with Boas's experiences on Baffin Island and drew him to anthropology.

At the Royal Ethnological Museum, Boas became interested in Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest. After defending his paper, he took a three-month trip to British Columbia through New York. In January 1887, he was offered a job as an assistant editor for the journal Science. Boas decided to stay in the United States. He was bothered by growing antisemitism and nationalism in Germany. Also, there were few jobs for geographers there. He might have also been motivated by his romance with Marie Krackowizer, whom he married that year.

Besides editing Science, Boas got a job teaching anthropology at Clark University in 1888. Boas was worried about the university president, G. Stanley Hall, interfering with his research. But in 1889, he became the head of a new anthropology department at Clark University. In the early 1890s, he went on trips called the Morris K. Jesup Expedition. These trips aimed to show connections between Asian and American cultures. In 1892, Boas and another professor resigned. They protested Hall's actions, which they felt limited academic freedom.

World's Fair and Museums

Frederic Ward Putnam, an anthropologist, was in charge of ethnology and archaeology for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. He chose Boas as his main assistant. This fair celebrated 400 years since Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas. Boas got to use his ideas for exhibits. He led a team of about 100 assistants. Their job was to create exhibits on Native Americans from North and South America. Putnam wanted the fair to celebrate Western achievements. He thought showing late 19th-century Inuit and First Nations people "in their natural conditions" would highlight this.

Franz Boas traveled north to collect items for the Exposition. He wanted to use the exhibits to teach visitors about other cultures. Boas arranged for 14 Kwakwakaʼwakw people from British Columbia to live in a pretend village. There, they could do their daily tasks. Inuit people were also there, showing their skills with sealskin whips and kayaks. But Boas found that visitors were not there to learn. By 1916, Boas realized that few people in America wanted to understand other cultures. He felt that Americans often judged the world only from their own viewpoint.

After the fair, the collected items became the start of the new Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Boas became the curator of anthropology there. He worked until 1894 when he was replaced.

In 1896, Boas became Assistant Curator of Ethnology and Somatology at the American Museum of Natural History. In 1897, he organized the Jesup North Pacific Expedition. This was a five-year study of groups in the Pacific Northwest. Their ancestors had crossed the Bering Strait from Siberia. Boas tried to arrange exhibits based on context, not on how cultures "evolved." He also created a research plan for his goals. He told his students to collect items, explanations, stories, and language information. He wanted collections arranged by tribe to show each group's unique style. However, his ideas clashed with the museum's president, Morris Jesup, and director, Hermon Bumpus. By 1900, Boas started to step away from museum work. He resigned in 1905 and never worked for a museum again.

Minik Wallace's Story

While at the American Museum of Natural History, Franz Boas asked explorer Robert Peary to bring an Inuit person from Greenland to New York. Peary brought six Inuit people in 1897. They lived in the museum's basement. Sadly, four of them died from tuberculosis within a year. One returned to Greenland. A young boy named Minik Wallace stayed at the museum. Boas arranged a funeral for Minik's father. Boas has been criticized for bringing the Inuit to New York and for not caring enough about them after they served their purpose at the museum.

Anthropology in Universities

Boas became a lecturer in physical anthropology at Columbia University in 1896. He became a full professor of anthropology in 1899. At Columbia, different anthropologists were in different departments. When Boas left the museum, he worked to bring these professors into one department. Boas led this new department. His program at Columbia was the first PhD program in anthropology in America.

During this time, Boas helped create the American Anthropological Association (AAA). This was a main group for the growing field. Boas wanted the AAA to be only for professional anthropologists. But William John McGee argued it should be open to everyone. McGee's idea won, and he became the first president in 1902. Boas became a vice-president.

At Columbia and the AAA, Boas pushed for the "four-field" idea of anthropology. He worked in physical anthropology, linguistics, archaeology, and cultural anthropology. His work in these areas was groundbreaking. In physical anthropology, he moved scholars away from fixed racial categories. He focused on human biology and how it changes. In linguistics, he went beyond old ways of studying languages. He set up key questions for modern linguistics. In cultural anthropology, he helped create the idea of studying culture in its context. He also promoted cultural relativism and the method of participant observation in fieldwork.

The four-field approach was a big contribution. It brought together different kinds of anthropological research. This made American anthropology different from that in England, France, or Germany. This approach sees the human species as a whole. Boas did not try to make all humans the same. Instead, he understood that the human species is special because of its huge variety in forms and activities. This is similar to Charles Darwin's ideas about species.

In his 1907 essay "Anthropology," Boas asked two main questions: "Why are the tribes and nations of the world different, and how have the present differences developed?" These questions were a big change from old ideas. Old ideas thought some people had history (written records) and others did not. Boas rejected this. He believed all societies have a history. All societies are important to study in anthropology. To study both literate and non-literate societies, he stressed studying human history through things other than written texts.

Historians and thinkers in the 18th and 19th centuries guessed why societies were different. But Boas rejected these guesses, especially theories of social evolution. He wanted to create a field that used careful, factual study.

One of Boas's most important books was The Mind of Primitive Man (1911). It combined his ideas about culture's history and growth. It set a plan for American anthropology for the next 15 years. In this book, he showed that in any group, biology, language, and culture are separate but equally important. None of these depends on another. He stressed that the traits of any group come from historical events. He showed that having many different cultures is a basic part of being human. He also showed that a specific cultural environment shapes much of how individuals act.

Boas also acted as a role model for scientists. He believed that even when seeking truth, all knowledge has moral effects.

Physical Anthropology Studies

Boas's work in physical anthropology combined his interest in Darwinian evolution with how migration causes change. His most important research was on how the bodies of immigrant children in New York changed. Other researchers had seen differences in height and head size between Americans and people from Europe. Many used these differences to say there were fixed biological differences between races. Boas wanted to see if body forms also changed over time.

Boas studied 17,821 people from seven different ethnic groups. He found that the average head size of immigrants was very different from those of their children born in the United States. Also, children born within ten years of their mothers arriving had different average head sizes than those born after ten years. Boas did not deny that traits like height or head size were inherited. But he argued that the environment also affects these traits, causing changes over time. This work was key to his idea that racial differences were not fixed.

These findings were new and are still debated. In 2002, some anthropologists said the differences Boas found were very small. They said the American environment had no clear effect on head shape. They argued their results went against Boas's findings. However, Jonathan M. Marks, a well-known physical anthropologist, said this new study seemed desperate. In 2003, other anthropologists re-analyzed Boas's data. They found that most of his original findings were correct. They used new computer methods and found more proof that head shape can change. They also argued that the 2002 study misunderstood Boas's claims. For example, Boas looked at changes based on how long the mother had been in the U.S. This is important because the environment before birth affects development.

Another study in 2005 claimed Boas chose only two groups (Sicilians and Hebrews) that showed the most change. It said he ignored others that changed in the opposite way.

Even though some scientists today suggest Boas was against Darwinian evolution, he actually supported it. In 1888, he said that anthropology grew a lot because of the idea of biological evolution. Since Boas's time, physical anthropologists have shown that our ability for culture comes from human evolution. Boas's research on body changes helped Darwinian theory grow. Boas studied when biologists did not understand genetics. Genetics became widely known only after 1900. Before that, biologists used physical measurements for evolution theories. Boas's studies made him question this method. In 1912, he said that statistics could only raise biological questions, not answer them. This led anthropologists to look at genetics for understanding biological differences.

Language Studies

Boas also greatly helped make linguistics a science in the United States. He wrote many descriptions of Native American languages. He also wrote about problems in classifying languages. He created a research plan for studying how language and culture are connected. His students, like Edward Sapir and Alfred Kroeber, followed this plan.

His 1889 article "On Alternating Sounds" was very important. It was a response to a paper by Daniel Garrison Brinton. Brinton said that in many Native American languages, certain sounds changed regularly. Brinton thought this showed that these languages were less developed.

Boas had heard similar sound changes during his research. But he argued that "alternating sounds" did not really exist in Native American languages. Instead of seeing them as proof of different stages of evolution, Boas looked at them based on his interest in how people hear things. He also thought about his earlier criticism of museum displays. He had shown that two similar-looking things might be very different. In this article, he suggested that two different-sounding things might actually be the same.

He focused on how people perceive different sounds. Boas asked: when people describe one sound in different ways, is it because they can't hear the difference, or is there another reason? He said he wasn't talking about hearing problems. He pointed out that describing one sound in different ways is like describing different sounds in one way. This is key for studying new languages. How do we write down how words are pronounced? People might say a word in many ways but still know it's the same word. The point is not that people don't notice differences. It's that they group similar sounds into one category. For example, the English word "green" can mean many shades. But some languages have no word for "green." People might call what we call "green" either "yellow" or "blue." This doesn't mean they can't see colors. It means they group similar colors differently than English speakers.

Boas used these ideas in his studies of Inuit languages. Researchers had written the same word in many ways. In the past, people thought this meant different pronunciations or dialects. Boas argued that the difference was not in how the Inuit said the word. It was in how English-speaking scholars heard the word. English speakers could hear the sound. But the English sound system could not easily write it down.

Boas was making a specific point about language study. But his bigger point was important: a researcher's own culture can affect what they see. The way Western researchers think might make them misunderstand or miss things in other cultures. Like his criticism of museum displays, Boas showed that what seemed like proof of cultural evolution was really due to unscientific methods. It also showed Westerners' beliefs about their own culture being better. This idea became the base for Boas's cultural relativism. It means that parts of a culture make sense in that culture's own terms. They might not make sense in another culture.

Cultural Anthropology Ideas

Boas's main idea for studying cultures comes from his early essay "The Study of Geography." He believed that to understand "what is" in a culture (its behaviors, beliefs, and symbols), you must look at them in their local setting. He also understood that as people move or as time passes, cultural elements and their meanings change. This made him stress the importance of local histories for understanding cultures.

Other anthropologists at the time focused on studying societies as clear, separate groups. But Boas looked at history. He saw how cultural traits spread from one place to another. This made him see cultural boundaries as many, overlapping, and easily crossed. So, Boas's student Robert Lowie once called culture a thing of "shreds and patches." Boas and his students knew that people try to make sense of their world by connecting different parts. This means cultures can have different patterns. But they also knew that this was always balanced with ideas spreading. Any stable pattern was temporary.

During Boas's life, many Westerners thought modern societies were active and individualistic. They thought traditional societies were stable and all the same. But Boas's research showed this was not true. For example, his 1903 essay on Alaskan needlecases showed how he made big ideas from small details. He found similar designs on needlecases. Then he showed how these designs gave artists a way to create new variations. So, he stressed that culture provides a setting for actions. This made him notice individual differences within a society.

In a 1920 essay, "The Methods of Ethnology," Boas argued that anthropology should not just list beliefs and customs. It needed to document "how individuals react to their social environment." It should also look at differences in ideas and actions within a society. These differences cause big changes. Boas said that focusing on individuals shows that "primitive society loses the appearance of absolute stability." All cultures are always changing.

Boas argued that societies with and without writing should be studied the same way. Historians in the 18th and 19th centuries used language study to rebuild the histories of societies with writing. To do this for societies without writing, Boas said fieldworkers needed to collect texts. This meant making lists of words, grammars, myths, folktales, and beliefs. To do this, Boas worked closely with native ethnographers who could write. He told his students to see these people as valuable partners. They might be seen as lower in Western society, but they understood their own culture best.

Using these methods, Boas wrote another article in 1920. He looked again at his earlier research on Kwakiutl family groups. In the 1890s, Boas had tried to figure out how Kwakiutl clans changed. He compared them to clans in nearby societies. Now, he argued against translating Kwakiutl family terms into English words. Instead of trying to fit the Kwakiutl into a bigger model, he tried to understand their beliefs in their own terms. For example, he had called the Kwakiutl word numaym a "clan." Now, he said it was better understood as a group of special rights. Men got these rights from their parents or wives. There were many ways to get, use, and pass on these rights. Like his work on sounds, Boas realized that different ways of understanding Kwakiutl family groups came from the limits of Western ideas. Like his work on needlecases, he now saw differences in Kwakiutl practices as a mix of social rules and individual creativity.

Before he died in 1942, he asked Helen Codere to edit and publish his writings about the Kwakiutl people.

Franz Boas and Folklore

Franz Boas was very important in the development of folklore as a field of study. He wanted both anthropology and folklore to be seen as serious and respected sciences. Boas worried that if folklore became its own field, its standards might drop. He thought this, along with work from "amateurs," would make folklore lose its credibility.

To make folklore more professional, Boas brought in strict scientific methods. He pushed for thorough research, fieldwork, and clear scientific rules in folklore studies. Boas believed that a true theory could only come from deep research. Even then, a theory should be seen as a "work in progress" until it was proven without doubt. These strict methods became a main part of folklore study, and Boas's methods are still used today. Boas also taught many new folklorists. Some of his students became very famous in folklore studies.

Boas loved collecting folklore. He believed that similar folktales in different groups spread from one to another. Boas tried to prove this idea. He created a way to break a folktale into parts and then study these parts. He used "catch-words" to sort these parts. This helped him compare them to other similar tales. Boas also fought to show that not all cultures developed in the same way. He argued that non-European cultures were not "primitive," just different.

Boas stayed active in folklore throughout his life. He became the editor of the Journal of American Folklore in 1908. He regularly wrote and published articles on folklore. He also helped elect Louise Pound as president of the American Folklore Society in 1925.

Scientist as Activist

Boas was known for strongly defending what he thought was right. During his life, he fought against racism. He criticized anthropologists who used their work to spy. He helped German and Austrian scientists who fled the Nazi regime. He also openly protested against Hitler's ideas.

Many social scientists in other fields worry if their work is "science." They often stress being separate, objective, and using numbers. Boas, like other early anthropologists, was trained in natural sciences. He and his students never worried about this. He did not think being separate was needed to make anthropology scientific. Since anthropologists study humans, they need different methods than physicists. Boas used statistics to show that differences in data depend on the situation. He argued that human differences, which depend on context, made many common ideas about humankind unscientific. His idea of fieldwork started with the fact that the people being studied were not just objects, but real people. His research showed their creativity and actions. He even saw the Inuit as his teachers. This flipped the usual idea of scientist and object.

This focus on the relationship between anthropologists and the people they study meant that anthropologists themselves could be studied. Boas's article on alternating sounds showed that scientists should not be too sure about their objectivity. They also see the world through their own culture.

This also led Boas to believe that anthropologists should speak out on social issues. Boas was especially concerned about racial inequality. His research showed that racism was not biological, but social. Boas is seen as the first scientist to publish the idea that all people, including white and African Americans, are equal. He often showed his hatred of racism. He used his work to prove there was no scientific reason for such bias. An early example is his 1906 speech at Clark Atlanta University. He was invited by W. E. B. Du Bois. Boas started by saying that even if people believed African Americans' weaknesses were inborn, their work would still be good. But then he argued against that idea. He said that compared to all of human history, the last two thousand years are a short time. He also said that early human inventions, like taming fire, might be bigger achievements than the steam engine. Boas then listed achievements in Africa, like melting iron and growing crops. These happened in Africa before they spread to Europe and Asia. He described the actions of African kings, traders, and artists as proof of cultural success.

Boas then talked about arguments for the "Negro race" being inferior. He pointed out that they were brought to the Americas by force. For Boas, this was just one example of how conquest can make different peoples unequal. He mentioned other examples like the Normans conquering England.

Boas's final advice was that African Americans should not seek approval from white people. He said people in power often take a long time to understand those without power. "Remember that in every single case in history the process of adaptation has been one of exceeding slowness. Do not look for the impossible, but do not let your path deviate from the quiet and steadfast insistence on full opportunities for your powers."

Boas also criticized one nation controlling others. In 1916, Boas wrote a letter to The New York Times. It was titled "Why German-Americans Blame America." Boas protested attacks against German Americans during the war in Europe. But most of his letter criticized American nationalism. He wrote about his love for American freedom. He also wrote about his growing discomfort with American beliefs about being better than others.

Boas believed scientists should speak out on social problems. But he was shocked when he found out that four anthropologists were spying for the American government during their research abroad. In 1919, he wrote an angry letter to The Nation.

Boas did not name the spies. But he was talking about a group led by Sylvanus Morley. Morley and his colleagues looked for German submarine bases in Mexico. They also gathered information on Mexican politicians and German immigrants.

Boas's stand against spying happened while he was trying to build a new model for anthropology at Columbia University. Before, American anthropology was mainly at the Smithsonian and Harvard. These anthropologists competed with Boas's students. When the National Academy of Sciences created the National Research Council in 1916, competition grew. Boas's rival, W. H. Holmes, was chosen to lead the NRC. Morley was Holmes's student.

When Boas's letter was published, Holmes complained about "Prussian control of anthropology in this country." He wanted to end Boas's "Hun regime." Holmes and his friends were influenced by anti-German and anti-Jewish feelings. The Anthropological Society of Washington condemned Boas's letter. They said it unfairly criticized President Wilson and endangered anthropologists abroad. This was especially insulting, as Boas wrote the letter because he was worried about spying. The American Anthropological Association (AAA) voted to criticize Boas. Boas resigned from the NRC, but stayed an active AAA member. The AAA did not remove its criticism of Boas until 2005.

Boas continued to speak out against racism and for intellectual freedom. When the Nazi Party in Germany attacked "Jewish Science" (including Boasian Anthropology and Einsteinian physics), Boas responded. He signed a public statement with over 8,000 other scientists. It said there is only one science, and race and religion do not matter. After World War I, Boas created the Emergency Society for German and Austrian Science. This group aimed to build good relations between American and German/Austrian scientists. It also gave money for research to German scientists affected by the war. And it helped scientists who had been held captive. With the rise of Nazi Germany, Boas helped German scientists escape the Nazi regime. He helped them find jobs once they arrived. Boas also wrote an open letter to Paul von Hindenburg protesting Hitlerism. He wrote an article saying there were no differences between Aryans and non-Aryans. He argued the German government should not base its policies on such a false idea.

Boas and his students, like Melville J. Herskovits, opposed the racist ideas from the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics. This institute was led by Eugen Fischer. Herskovits showed that health problems and prejudice faced by mixed-race children were not due to biology. Fischer then strongly criticized Boas. He said Boas was not good enough in the field of heredity. But many studies at Fischer's own institute had confirmed Boas's findings. Fischer used harsh words because he had no real arguments against Boas's ideas.

Students and Influence

Franz Boas died suddenly on December 21, 1942, at Columbia University. He was with Claude Lévi-Strauss. By then, he was one of the most important and respected scientists of his time.

Between 1901 and 1911, Columbia University gave out seven PhDs in anthropology. This might seem small today, but it made Boas's department the best in the country. Many of Boas's students went on to start anthropology programs at other big universities.

Boas's first PhD student at Columbia was Alfred L. Kroeber (1901). Kroeber, with another Boas student Robert Lowie (1908), started the anthropology program at the University of California, Berkeley. Boas also taught William Jones (1904). Jones was one of the first Native American anthropologists. He died doing research in the Philippines in 1909. Albert B. Lewis (1907) was also his student.

Boas trained many other students who shaped academic anthropology:

- Frank Speck (1908) started the anthropology department at the University of Pennsylvania.

- Edward Sapir (1909) and Fay-Cooper Cole (1914) developed the program at the University of Chicago.

- Alexander Goldenweiser (1910) and Elsie Clews Parsons started the program at the New School for Social Research.

- Leslie Spier (1920) started the program at the University of Washington with his wife Erna Gunther, also a Boas student.

- Melville Herskovits (1923) started the program at Northwestern University.

Other students included John R. Swanton (who studied with Boas before getting his PhD from Harvard), Paul Radin (1911), Ruth Benedict (1923), Gladys Reichard (1925), Ruth Bunzel (1929), Alexander Lesser (1929), Margaret Mead (1929), Gene Weltfish, E. Adamson Hoebel (1934), Jules Henry (1935), George Herzog (1938), and Ashley Montagu (1938).

His students also included Mexican anthropologist Manuel Gamio. Gamio became the first director of Mexico's Bureau of Anthropology. Clark Wissler studied anthropology with Boas. Esther Schiff Goldfrank did research among the Cochiti and Laguna Pueblo Indians. Gilberto Freyre shaped the idea of "racial democracy" in Brazil. Viola Garfield continued Boas's work on the Tsimshian people. Frederica de Laguna worked on the Inuit and Tlingit people. Anthropologist, folklorist, and writer Zora Neale Hurston studied African American and Afro-Caribbean folklore. Ella Cara Deloria worked closely with Boas on Native American languages.

Boas and his students also influenced Claude Lévi-Strauss. Lévi-Strauss met Boas and his students when he was in New York in the 1940s.

Several of Boas's students became editors of the main journal for the American Anthropological Association, American Anthropologist.

Most of Boas's students shared his focus on careful, historical study. They also disliked theories that guessed about evolution. Boas encouraged his students to criticize their own work. For example, Boas first supported using head shape (cephalic index) to describe inherited traits. But he later rejected his own research after more study. He also criticized his early work on Kwakiutl language and myths.

Boas's students were encouraged to learn from the people they studied. They let their research findings guide their work. Because of this, Boas's students soon explored ideas different from his own. Some tried to create big theories that Boas usually rejected. Kroeber suggested combining anthropology with psychoanalysis. Ruth Benedict developed theories about "culture and personality." Kroeber's student, Julian Steward, developed theories about "cultural ecology."

His Lasting Impact

Boas has had a lasting impact on anthropology. Almost all anthropologists today accept Boas's focus on facts and his method of cultural relativism. Also, almost all cultural anthropologists today follow Boas's idea of fieldwork. This means living with the people being studied for a long time, learning their language, and building relationships. Finally, anthropologists still honor his fight against racist ideas. In his 1963 book, Race: The History of an Idea in America, Thomas Gossett wrote that "It is possible that Boas did more to combat race prejudice than any other person in history."

Leadership and Awards

- 1887—Became Assistant Editor of Science in New York.

- 1889—Appointed head of a new anthropology department.

- 1896—Became assistant curator at the American Museum of Natural History. He also lectured at Columbia University.

- 1900—Elected to the National Academy of Sciences in April.

- 1901—Named Honorary Philologist of the Bureau of American Ethnology.

- 1903—Elected to the American Philosophical Society.

- 1908—Became editor of The Journal of American Folklore.

- 1908—Elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.

- 1910—Helped create the International School of American Archeology and Ethnology in Mexico.

- 1910—Elected president of the New York Academy of Sciences.

- 1913—Became founding editor of Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology.

- 1917—Founded the International Journal of American Linguistics.

- 1917—Edited the Publications of the American Ethnological Society.

- 1931—Elected president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- 1936—Became "emeritus in residence" at Columbia University. Became "emeritus" in 1938.

Writings

- Boas n.d. "The relation of Darwin to anthropology", notes for a lecture; Boas papers (B/B61.5) American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia. Published online by Herbert Lewis 2001b.

- Boas, Franz (1889). The Houses of the Kwakiutl Indians, British Columbia.. Proceedings of the United States National Museum.. 11. Washington D.C., United States National Museum. pp. 197–213. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.11-709.197. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/13090/USNMP-11_709_1889.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Smithsonian Research Online.

- Boas, Franz (1895). The Social Organization and the Secret Societies of the Kwakiutl Indians.. Report of the United States National Museum.. Washington D.C., United States National Museum. pp. 197–213. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/29967/Boas_1895_309-738.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Smithsonian Research Online.

- Boas, Franz (1897). "The Decorative Art of the Indians of the North Pacific Coast.". Science. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. (New York, American Museum of Natural History) IX, Article X. (82): 101–3. doi:10.1126/science.4.82.101. PMID 17747165. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/handle/2246/539//v2/dspace/ingest/pdfSource/bul/B009a10.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. AMNH Digital Repository.

- Boas, Franz (1898). The Mythology of the Bella Coola Indians.. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Publications of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition.. II, Pt. II.. New York, American Museum of Natural History. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/handle/2246/31//v2/dspace/ingest/pdfSource/mem/M02Pt02.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. AMNH Digital Repository.

- Teit, James; Boas, Franz (1900). The Thompson Indians of British Columbia. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. The Jesup North Pacific Expedition.. II, Pt. IV.. New York, American Museum of Natural History. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/handle/2246/13//v2/dspace/ingest/pdfSource/mem/M02Pt04.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. AMNH Digital Repository.

- Boas, Franz (1901). A Bronze Figurine from British Columbia.. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History.. XIV, Article X.. New York, American Museum of Natural History. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/handle/2246/1543//v2/dspace/ingest/pdfSource/bul/B014a05.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. AMNH Digital Repository.

- Boas, Franz; Hunt, George (1902). Kwakiutl Texts.. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Publications of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition.. V, Pt. I. New York, American Museum of Natural History. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/handle/2246/23//v2/dspace/ingest/pdfSource/mem/M05Pt01.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y. AMNH Digital Repository.

- Boas, Franz; Hunt, George (1902). Kwakiutl Texts.. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Publications of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition.. V, Pt. II. New York, American Museum of Natural History. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/handle/2246/23//v2/dspace/ingest/pdfSource/mem/M05Pt02.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y. AMNH Digital Repository.

- Boas, Franz; Hunt, George (1905). Kwakiutl Texts.. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Publications of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition.. V, Pt. III. New York, American Museum of Natural History. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/handle/2246/23//v2/dspace/ingest/pdfSource/mem/M05Pt03.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. AMNH Digital Repository.

- Boas, Franz; Hunt, George (1906). Kwakiutl Texts - Second Series. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Publications of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition.. X, Pt. I.. New York, American Museum of Natural History. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/handle/2246/22//v2/dspace/ingest/pdfSource/mem/M14Pt01.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. AMNH Digital Repository.

- Boas, Franz (1906). The Measurement of Differences Between Variable Quantities. New York: The Science Press. (Online version at the Internet Archive)

- Boas, Franz (1909). The Kwakiutl of Vancouver Island.. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Publications of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition.. II, Pt. II.. New York, American Museum of Natural History. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/handle/2246/15//v2/dspace/ingest/pdfSource/mem/M08Pt02.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. AMNH Digital Repository.

- Boas, Franz. (1911). Handbook of American Indian languages (Vol. 1). Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 40. Washington: Government Print Office (Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology).

- Boas, Franz (1911). The Mind of Primitive Man. ISBN: 978-0-313-24004-1 (Online version of the 1938 revised edition at the Internet Archive)

- Boas, Franz (1912). "Changes in the Bodily Form of Descendants of Immigrants". American Anthropologist, Vol. 14, No. 3, July–Sept 1912. Boas

- Boas, Franz (1912). "The History of the American Race". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences XXI (1): 177–183. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1911.tb56933.x. https://zenodo.org/record/1447691.

- Boas, Franz (1914). "Mythology and folk-tales of the North American Indians". Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 27, No. 106, Oct.-Dec. pp. 374–410.

- Boas, Franz (1917) (DJVU). Folk-tales of Salishan and Sahaptin tribes. Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection.. Published for the American Folk-Lore Society by G.E. Stechert. http://www.secstate.wa.gov/history/publications_detail.aspx?p=42.

- Boas, Franz (1917). "Kutenai Tales". Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin. Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection. (Smithsonian Institution.) 59. https://www.sos.wa.gov/legacy/images/publications/sl_boaskutenai/sl_boaskutenai.pdf. Classics in Washington History: Native Americans.

- Boas, Franz (1922). "Report on an Anthropometric Investigation of the Population of the United States". Journal of the American Statistical Association, June 1922.

- Boas, Franz (1927). "The Eruption of Deciduous Teeth Among Hebrew Infants". The Journal of Dental Research, Vol. vii, No. 3, September 1927.

- Boas, Franz (1927). Primitive Art. ISBN: 978-0-486-20025-5

- Boas, Franz (1928). Anthropology and Modern Life (2004 ed.) ISBN: 978-0-7658-0535-5 (Online version of the 1962 edition at the Internet Archive)

- Boas, Franz (1935). "The Tempo of Growth of Fraternities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 413–418, July 1935.

- Boas, Franz (1940). Race, Language, and Culture ISBN: 978-0-226-06241-9

- Boas, Franz, ed. (1944) (in en). General Anthropology. United States Armed Forces. https://books.google.com/books?id=rbIsAAAAIAAJ. "Volume 226 of War Department Education Manual" (D.C. Heath, 1938)

- Boas, Franz (1945). Race and Democratic Society, New York, Augustin.

- Stocking, George W. Jr., ed. 1974 A Franz Boas Reader: The Shaping of American Anthropology, 1883–1911 ISBN: 978-0-226-06243-3

- Boas, Franz, edited by Helen Codere (1966), Kwakiutl Ethnography, Chicago, Chicago University Press.

- Boas, Franz (2006). Indian Myths & Legends from the North Pacific Coast of America: A Translation of Franz Boas' 1895 Edition of Indianische Sagen von der Nord-Pacifischen Küste-Amerikas. Vancouver, BC: Talonbooks. ISBN: 978-0-88922-553-4

See also

In Spanish: Franz Boas para niños

In Spanish: Franz Boas para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |