Julian Steward facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Julian Haynes Steward

|

|

|---|---|

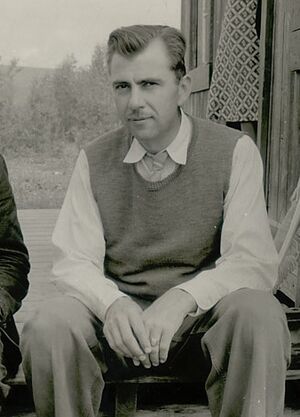

Steward in 1940

|

|

| Born | January 31, 1902 Washington, D.C., U.S.

|

| Died | February 6, 1972 (aged 70) Urbana, Illinois, U.S.

|

| Education | Deep Springs College Cornell University (BS) University of California, Berkeley (MA, PhD) |

| Occupation | Anthropologist |

| Spouse(s) | Dorothy Nyswander (1894–1998) (married 1930–1932); Jane Cannon Steward (1908–1988) (married 1933–1972) |

| Children | Garriott Steward

Michael Steward two grandchildren |

Julian Haynes Steward (born January 31, 1902 – died February 6, 1972) was an American anthropologist. He is best known for creating the idea of "cultural ecology." This is a way of studying how people and their environment interact. He also developed a scientific way to understand how cultures change over time.

Early Life and Learning

Julian Steward was born in Washington, D.C.. He grew up there, living on Monroe Street and later Macomb Street.

When he was 16, Steward left home to attend a boarding school. This school was in Deep Springs Valley, California, in the Great Basin. His time at Deep Springs Preparatory School (now Deep Springs College) was very important. It helped him decide what he wanted to study and do in his life.

While at school, Steward spent time directly with the land. He learned about farming using irrigation and ranching. He also met the Northern Paiute Native Americans who lived there. These experiences helped him form his ideas about cultural ecology.

As a college student, Steward first studied at UC Berkeley. He learned from famous professors like Alfred Kroeber. Later, he moved to Cornell University and graduated in 1925 with a science degree in zoology. Even though Cornell did not have an anthropology department, its president, Livingston Farrand, encouraged Steward. Farrand told him to follow his interest in anthropology at Berkeley.

Steward went back to Berkeley to study anthropology. In 1929, he finished his PhD. His main project was about "ritualized clowning" among American Indian groups.

A Career in Anthropology

Steward later started an anthropology department at the University of Michigan. He taught there until 1930. After that, he moved to the University of Utah. He liked Utah because it was close to the Sierra Nevada mountains. This area offered many chances to do archaeological fieldwork. He worked in California, Nevada, Idaho, and Oregon.

Steward was very interested in "subsistence." This means how people get food and resources to live. He studied how people, their environment, technology, and social groups all work together. His ideas were seen as new and original by other anthropologists.

In 1935, Steward got a job at the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnography (BAE). Here, he published some of his most important works. One key book was Basin-Plateau Aboriginal Sociopolitical Groups (1938). This book fully explained his idea of cultural ecology. It also helped change how American anthropology was studied.

For eleven years, Steward was an important leader in his field. He edited the Handbook of South American Indians. He also started the Institute for Social Anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution in 1943. He helped reorganize the American Anthropological Association. He also played a part in creating the National Science Foundation.

Steward was also active in archaeology. He worked to create the Committee for the Recovery of Archaeological Remains. This was the start of what is now called 'salvage archaeology.' He also worked with Gordon Willey on a big research project in Peru called the Viru Valley project.

Steward looked for patterns across different cultures. He wanted to find rules about how cultures change. His work showed that how complex a society is depends on its environment. He called his idea of cultural evolution "multi-linear." This was different from older ideas that said all cultures evolve in the same way.

Steward's most important ideas came during his time teaching at Columbia University (1946–1953). Many World War II veterans were attending school then. Steward taught many students who became very important anthropologists. These included Sidney Mintz, Eric Wolf, and Morton Fried. Many of these students worked on the Puerto Rico Project. This was a large study about how Puerto Rico was changing.

Steward left Columbia for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He led the Anthropology Department there until he retired in 1968. He started another big study there. It compared how eleven different "third world" societies were changing. The results were published in three books called Contemporary Change in Traditional Societies. Steward passed away in 1972.

His Work and Impact

Julian Steward is best remembered for his ideas and methods in cultural ecology. Before him, many American anthropologists focused on very detailed studies of single cultures. Steward was different because he tried to find general rules about how societies work.

His theory of "multilinear" cultural evolution looked at how societies adapt to their environment. This idea was more detailed than other theories at the time. Steward was also one of the first anthropologists to study how local communities connect with larger national societies.

Steward believed it was possible to create theories about common cultures. These theories could describe cultures from specific times or regions. He thought that technology and economics were the main things that shaped a culture's development. But he also noted that other things, like political systems and religions, were important too. These factors cause a society to change in many ways at the same time.

Steward first focused on ecosystems and physical environments. But he soon became interested in how these environments could influence cultures. During his time at Columbia, he wrote many important papers. These papers covered topics like cultural evolution, prehistory, archaeology, and how local cultures relate to national ones.

For example, his work on the Great Basin showed that people are largely defined by how they make a living. This idea also led him to study how people who farmed small plots of land became part of larger national workforces in South America.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |