Wilhelm Wundt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wilhelm Wundt

|

|

|---|---|

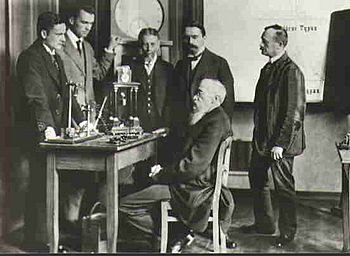

Wilhelm Wundt in 1902

|

|

| Born | 16 August 1832 |

| Died | 31 August 1920 (aged 88) Großbothen, Saxony, Germany

|

| Education | University of Heidelberg (MD, 1856) |

| Known for | Experimental psychology Cultural psychology Structuralism Apperception |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Experimental psychology, Cultural psychology, philosophy, physiology |

| Institutions | University of Leipzig |

| Thesis | Untersuchungen über das Verhalten der Nerven in entzündeten und degenerierten Organen (Research of the Behaviour of Nerves in Inflamed and Degenerated Organs) (1856) |

| Doctoral advisor | Karl Ewald Hasse |

| Other academic advisors | Hermann von Helmholtz Johannes Peter Müller |

| Doctoral students | James McKeen Cattell, G. Stanley Hall, Oswald Külpe, Hugo Münsterberg, Ljubomir Nedić, Walter Dill Scott, George M. Stratton, Edward B. Titchener, Lightner Witmer |

| Influences | Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Immanuel Kant, Gustav Theodor Fechner, Johann Friedrich Herbart |

| Influenced | James Mark Baldwin, Emil Kraepelin, Sigmund Freud, Moritz Schlick |

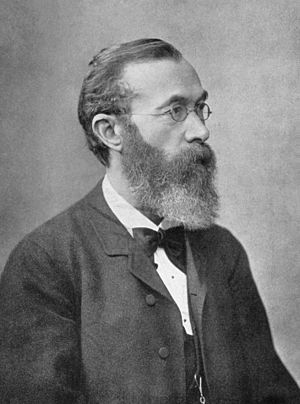

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (16 August 1832 – 31 August 1920) was a German scientist who is often called one of the founders of modern psychology. Psychology is the study of the mind and how it affects behavior. Wundt was the first person to call himself a psychologist. He is also known as the "father of experimental psychology". This means he was the first to use scientific experiments to study the mind.

In 1879, Wundt opened the first official laboratory for psychological research at the University of Leipzig. This was a big step because it made psychology its own field of study, separate from philosophy and biology. He also started the first academic journal for psychology, called Philosophische Studien, to share the research done at his lab. A survey in 1991 ranked Wundt as the most important psychologist of all time.

About Wilhelm Wundt

His Early Life and Education

Wilhelm Wundt was born in Neckarau, a town near Mannheim, Germany, on August 16, 1832. He was the fourth child of Maximilian Wundt, a minister, and Marie Frederike. When he was about six, his family moved to Heidelsheim.

Wundt grew up in Germany during a time when the country was doing well economically. People were investing money in education, medicine, and new technologies. This focus on learning helped Wundt develop his new way of studying psychology.

He studied at several universities, including the University of Tübingen, the University of Heidelberg, and the University of Berlin. He became a doctor of medicine in 1856. After that, he worked at Heidelberg University, helping a famous scientist named Hermann von Helmholtz. Wundt taught physiology, which is the study of how living things work.

Even though he was trained in medicine, Wundt was more interested in psychology. He wrote important books like Principles of Physiological Psychology in 1874. This was the first textbook about experimental psychology.

His Family Life

In 1867, Wundt met Sophie Mau. They got married on August 14, 1872. They had three children: Eleanor, Louise (who sadly died young), and Max, who later became a philosophy professor. Eleanor often helped her father with his work.

Working in Zurich and Leipzig

In 1875, Wundt became a professor in Zurich. Later that year, he moved to the University of Leipzig as a professor of philosophy. Leipzig was a great place for him because other scientists there, like Ernst Heinrich Weber and Gustav Fechner, were already studying how our senses work. Wundt admired Weber and even called him the "father of experimental psychology" for his work on measuring how people sense things.

The First Psychology Lab

In 1879, Wundt opened the very first laboratory just for psychological studies at the University of Leipzig. This moment is seen as the official start of psychology as its own science. Students from all over the world came to this lab to learn about Wundt's new science.

The university gave Wundt a lab space in 1876 to keep his equipment. He gathered many tools like tachistoscopes (for showing quick images), chronoscopes (for measuring time), and other devices. He would give students instruments and ask them to find new ways to use them for research.

Wundt started doing experiments that were not just for his classes in 1879. He felt these experiments proved his lab was a real psychology lab. The university officially recognized it in 1883. The lab grew to eleven rooms and was called the Psychological Institute. It eventually moved to a new building that Wundt designed specifically for psychological research.

Wundt's Students

Wundt taught many students between 1875 and 1919. He guided 184 students through their doctoral studies, including 70 from other countries. Many of his students became famous psychologists themselves.

Some of his German students included Oswald Külpe and Hugo Münsterberg, who became important professors. From America, students like James McKeen Cattell (the first psychology professor in the U.S.), G. Stanley Hall (known as the father of child psychology), and Edward B. Titchener went on to make big contributions.

Because of all his students, Wundt is connected to the academic "family tree" of most American psychologists.

Retirement and Death

Wundt retired in 1917 to focus on his writing. He passed away peacefully on August 31, 1920, shortly after his 88th birthday. He is buried in Leipzig's South Cemetery with his wife, Sophie.

Awards and Recognition

Wundt received special honorary degrees from the Universities of Leipzig and Göttingen. He also received the Pour le Mérite award for Science and Arts, which is a very high honor in Germany. He was nominated three times for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Wundt was an honorary member of many scientific groups. An Asteroid was even named after him, called Vundtia (635).

Wundt's Main Ideas

Wundt started as a doctor and brain scientist. He realized that understanding how we see things, for example, wasn't just about how our eyes and brain work. It also involved how our minds process information.

He created experimental psychology as a field and was also a pioneer in cultural psychology. This is the study of how culture affects our minds. He brought together many different areas of study.

How We Experience Things

Wundt believed that psychology studies our "immediate experience." This means looking at how our minds change and how things like perception (what we see), cognition (how we think), emotion (what we feel), and volition (our will or motivation) are connected. He saw mental events as changing processes of our consciousness.

Mind and Body Connection

Wundt used the idea of psychophysical parallelism. This means that mental processes and physical processes (like brain activity) happen at the same time, or "parallel" to each other. They are not the same, and one doesn't cause the other directly. Instead, they are linked in a regular way. For example, when you feel happy (a mental process), certain things happen in your brain (a physical process).

Apperception: Focusing Our Minds

Apperception was a very important idea for Wundt. It describes the process where simple sensory information becomes part of our (self-)consciousness. It's about how we actively choose to pay attention to certain things and how our minds organize and combine different thoughts and feelings.

Wundt believed that our minds are not just passively taking in information. Instead, they are actively creating and combining experiences. This "creative synthesis" means that the whole experience is more than just the sum of its parts. For example, when you look at a picture, you don't just see individual dots of color. Your mind puts them together to create a meaningful image.

Cultural Psychology: How Society Shapes Us

Wundt's huge 10-volume work, Völkerpsychologie (which means Cultural Psychology), explored how human societies develop and create things like language, myths, customs, art, and laws. He believed that to understand the human mind fully, you had to look at how it develops within a culture.

He studied how thinking, language, imagination, religion, and customs change over time. He said that where experiments end, history helps psychologists by showing how human societies have "experimented" over time.

The ten volumes covered topics like language, art, myths and religion, society, law, and culture and history. Wundt looked at how different values and motives, like division of labor, art, and justice, influenced cultural development.

He also described four main stages of cultural development: primitive man, the totemistic age, the age of heroes and gods, and the development of humanity.

Neuropsychology: Brain and Mind

Wundt also studied how the brain works with the mind. He believed that to understand how our brains control higher functions like attention, we needed to combine both psychological and brain research. He suggested that a special "apperception center" in the frontal cortex (the front part of the brain) helps connect our senses, movements, thoughts, feelings, and motivations.

This idea was ahead of its time. It's similar to how scientists today study how different parts of the brain work together for complex tasks.

How Wundt Studied Psychology

Wundt believed psychology should be a scientific field. He used different methods to study the mind:

- Experimental Methods: He used controlled experiments, especially in his lab, to study things like how quickly people react to stimuli or how they perceive different sensations. He used tools to measure things like pulse and breathing to see how they changed with emotions.

- Observation and Interpretation: For cultural psychology, he studied historical writings, languages, art, and reports of human behavior from different cultures. He believed that by interpreting these "objective works," psychologists could understand how the mind develops in society.

- Comparing Ideas: He compared different ideas and observations to find general patterns and types of mental processes.

Wundt's approach was to use many different methods, both experimental and observational, to get a full picture of the human mind. He believed that psychology should not just focus on one way of studying things.

Wundt's Philosophy

Wundt was also a philosopher. He believed that philosophy helps sciences understand their basic ideas. He thought that psychology, as a science, should be connected to philosophy.

He was influenced by philosophers like Gottfried Leibniz and Immanuel Kant. Wundt took some of their ideas, like the connection between mind and body, and applied them to his new science of psychology. He believed that our will and our ability to set goals are central to being human.

Wundt also wrote about ethics, which is the study of moral principles. He thought that understanding how people's minds work and how cultures develop was important for understanding what is right and wrong. He believed that ethical rules change as human thought develops culturally.

His Legacy

Wundt wrote a huge number of books and articles – over 500 publications! His work totals more than 53,000 pages. This shows how dedicated he was to developing psychology.

His personal library was partly sold to Tohoku University in Japan after World War I. His letters and other writings are kept in libraries in Leipzig and Tübingen, Germany. You can even hear a recording of Wundt's voice from 1918, where he repeats the closing words of one of his lectures.

Wundt's ideas helped shape psychology into the science it is today. He created the first complete theory of psychology, showing that it's a unique science that combines ideas from brain science, philosophy, and the study of human culture. He taught that humans are thinking and motivated beings who cannot be fully understood by just looking at them like objects in nature. Psychology needs its own special ways of studying the mind.

Images for kids

-

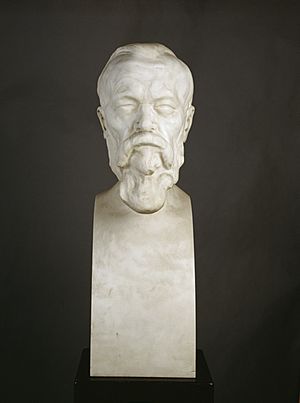

Wilhelm Wundt portrait bust by Max Klinger 1908

Selected Works

- Lehre von der Muskelbewegung (The Patterns of Muscular Movement), (1858).

- Die Geschwindigkeit des Gedankens (The Velocity of Thought), (1862).

- Beiträge zur Theorie der Sinneswahrnehmung (Contributions on the Theory of Sensory Perception), (1862).

- Vorlesungen über die Menschen- und Tierseele (Lectures about Human and Animal Psychology), (1863/1864).

- Lehrbuch der Physiologie des Menschen (Textbook of Human Physiology), (1864/1865).

- Grundzüge der physiologischen Psychologie (Principles of physiological Psychology), (1874).

- Völkerpsychologie (Cultural Psychology), 10 Volumes, (1900 to 1920).

- Erlebtes und Erkanntes (Experience and Realization), (1920).

Wundt's Works in English

- The Language of Gestures. (1974).

- An Introduction to Psychology. (1973).

- Outlines of Psychology. (1897).

- Elements of Folk Psychology. (1916).

- The Principles of Morality and the Departments of the Moral Life. (1901).

- Lectures on human and animal psychology. (1896).

- Principles of physiological psychology. (1893).

See also

In Spanish: Wilhelm Wundt para niños

In Spanish: Wilhelm Wundt para niños

- Anti-psychologism

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |