Emil Kraepelin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Emil Kraepelin

|

|

|---|---|

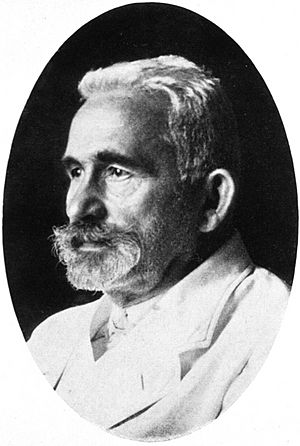

Emil Kraepelin in his later years

|

|

| Born | 15 February 1856 Neustrelitz, Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, German Confederation

|

| Died | 7 October 1926 (aged 70) |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | Leipzig University University of Würzburg (MBBS, 1878) Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (Dr. hab. med., 1882) |

| Known for | Classification of mental disorders, Kraepelinian dichotomy |

| Spouse(s) | Ina Marie Marie Wilhelmine Schwabe |

| Children | 2 sons, 6 daughters |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychiatry |

| Institutions | University of Dorpat University of Heidelberg Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich |

| Thesis | The Place of Psychology in Psychiatry (1882) |

| Influences | Wilhelm Wundt Bernhard von Gudden Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum |

| Influenced | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems |

| Signature | |

Emil Wilhelm Georg Magnus Kraepelin (born February 15, 1856 – died October 7, 1926) was an important German psychiatrist. He is often called the founder of modern scientific psychiatry. This means he helped make the study of mental health a real science.

He also helped start the fields of psychopharmacology (studying how medicines affect the mind) and psychiatric genetics (studying how genes influence mental health).

Kraepelin believed that mental illnesses were mainly caused by problems in the body or genes. His ideas were very important in psychiatry in the early 1900s. Even though other ideas came along later, his work is still very influential today. He focused on carefully observing patients and gathering information.

Early Life and Family

Emil Kraepelin was born in 1856 in Neustrelitz, Germany. His father, Karl Wilhelm, was a music teacher and storyteller.

Emil became interested in biology thanks to his older brother, Karl. Karl later became the director of the Zoological Museum of Hamburg.

Education and Career

Kraepelin began studying medicine in 1874 at the University of Leipzig. He finished his studies at the University of Würzburg in 1878. At Leipzig, he studied how the brain works and how the mind works. He was a student of Wilhelm Wundt, who is known as the father of experimental psychology. Kraepelin was always interested in using experiments to understand the mind.

After finishing his medical degree, he worked at the University of Munich from 1878 to 1882. He then returned to Leipzig to continue his research.

In 1883, Kraepelin published his main work, Compendium of Psychiatry. This book was for students and doctors. In it, he argued that psychiatry should be studied like other sciences. He believed doctors should observe patients and do experiments.

He wanted to find the physical causes of mental illness. He also started to create a system for classifying different mental disorders. Kraepelin thought that by studying how illnesses developed over time, doctors could predict how a mental illness might progress.

In 1886, at age 30, Kraepelin became a professor of psychiatry at the University of Dorpat (now in Estonia). There, he began to record many detailed patient histories. This helped him understand the importance of how an illness changed over time for classifying mental disorders.

He later moved to the University of Heidelberg and then to the University of Munich in 1903.

In 1912, Kraepelin started planning a research center for psychiatry. With help from donations, the German Institute for Psychiatric Research was founded in Munich in 1917. This institute became a major center for studying mental health.

Kraepelin spoke out against the harsh treatment of patients in mental asylums of his time. He believed that people with mental illness should be treated, not just locked away. He also focused on collecting detailed information about patients and studying diseased brain tissue.

In his later career, Kraepelin supported ideas about eugenics. This was a belief that the human race could be improved by controlling who had children. He was concerned about the health and strength of the German people. He thought that social programs might stop natural selection.

Kraepelin retired from teaching at 66. He spent his last years working on his institute. The final edition of his main textbook was published shortly after he died in 1926. It was much larger than his first book, showing how much his knowledge had grown.

Influence

Kraepelin's ideas about classifying mental illnesses, like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which he called manic depression), were very important. Even though his work was not as widely read as Sigmund Freud's for a while, his ideas are now central to much psychiatric research.

His basic ideas for diagnosing mental disorders are used in today's main diagnostic systems. These include the American Psychiatric Association's DSM-IV and the World Health Organization's ICD system. These systems help doctors around the world understand and diagnose mental health conditions.

Kraepelin was known for being a good organizer and leader in science. He gathered information from many sources to build his research programs. He wrote in a clear and direct way, which made his books very helpful for doctors.

Among the doctors who trained with Kraepelin were important Spanish scientists like Nicolás Achúcarro and Gonzalo Rodríguez Lafora.

See also

In Spanish: Emil Kraepelin para niños

In Spanish: Emil Kraepelin para niños

- Kraepelinian dichotomy

- History of bipolar disorder

- History of schizophrenia

- Psychiatric hospital