Robert Peary facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Peary

|

|

|---|---|

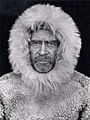

At Cape Sheridan on Ellesmere Island, 1909

|

|

| Born |

Robert Edwin Peary

May 6, 1856 Gallitzin, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Died | February 20, 1920 (aged 63) Washington, D.C., U.S.

|

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Bowdoin College |

| Known for | Claim to have reached the geographic North Pole on his travels with Matthew Henson. |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 4 |

| Awards |

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Branch | |

| Service years | 1881–1911 |

| Rank | Rear admiral |

| Unit | Civil Engineer Corps |

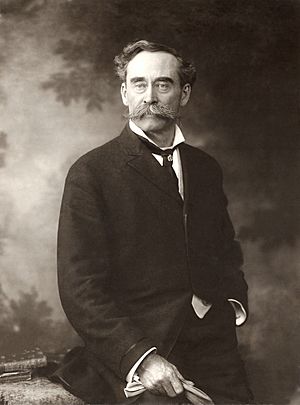

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy. He is famous for his trips to the Arctic in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In April 1909, he led an expedition that claimed to be the first to reach the geographic North Pole.

Peary was born in Gallitzin, Pennsylvania. After his father passed away, he grew up in Portland, Maine. He went to Bowdoin College and later joined the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey as a draftsman. In 1881, he joined the Navy as a civil engineer. He first visited the Arctic in 1886, trying to cross Greenland by dogsled.

In 1891–1892, Peary proved that Greenland was an island. He was one of the first Arctic explorers to learn from Inuit survival techniques. During an expedition in 1894, he found the Cape York meteorite fragments. These were important to the Inuit for making tools. Peary brought some Inuit people to America for study. He promised they would return home, but sadly, some of them became sick and could not go back.

On his 1898–1902 expedition, Peary reached Cape Morris Jesup, the northernmost point of Greenland. He made two more Arctic trips in 1905–1906 and 1908–1909. During the last one, he claimed to have reached the North Pole. Peary received many awards for his explorations. In 1911, he was promoted to rear admiral and retired. While his claim to the North Pole was debated, it was widely accepted for a time. Later, in 1989, explorer Wally Herbert suggested Peary might not have reached the exact pole.

Contents

Who Was Robert Peary?

Robert Edwin Peary was born on May 6, 1856, in Gallitzin, Pennsylvania. When he was three, his father died, and he moved with his mother to Portland, Maine. He went to Portland High School (Maine) and graduated in 1873.

Peary then attended Bowdoin College, about 36 miles north. He was part of a fraternity and an honor society. He also joined the rowing team. In 1877, he earned a degree in civil engineering.

After college, Peary worked as a draftsman, drawing technical plans in Washington, D.C. He joined the United States Navy in 1881 as a civil engineer. From 1884 to 1885, he helped survey for the Nicaragua Canal, which was never built. In 1885, he wrote in his diary that he wanted to be the first person to reach the North Pole.

In 1886, he wrote a paper about crossing Greenland's ice cap. One idea was to travel about 400 miles from the west to the east coast. Another, harder idea was to go north from Whale Sound to see if Greenland was an island or connected to the Arctic. Peary was promoted to lieutenant commander in 1901 and commander in 1902.

Early Arctic Adventures

Peary's first trip to the Arctic was in 1886. He wanted to cross Greenland by dog sled. He got six months off from the Navy and $500 from his mother for the trip. He sailed to Greenland and arrived in Godhavn on June 6, 1886.

Peary wanted to go alone, but a Danish official named Christian Maigaard convinced him it was too dangerous. So, Maigaard and Peary went together. They traveled almost 100 miles east before turning back because they ran out of food. This was one of the farthest trips into Greenland's ice sheet at that time. Peary learned a lot about what it takes to travel long distances on ice.

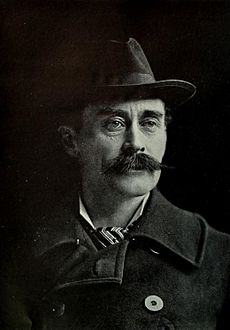

Back in Washington, Peary met 21-year-old Matthew Henson in 1887. Henson was a sales clerk with six years of experience at sea. Peary hired him as his personal assistant.

In Nicaragua, Peary told Henson about his dream of exploring the Arctic. Henson joined Peary on all his future Arctic trips. He became Peary's main field assistant and a very important part of his team.

Exploring Greenland Again

In the Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892, Peary tried the harder route he had planned. He wanted to go farther north to see if Greenland was a huge landmass reaching the North Pole. Several groups helped pay for this trip.

Peary's team included Henson, Frederick Cook (the surgeon), Eivind Astrup (a skier), Langdon Gibson (a bird expert), and John M. Verhoeff (a weatherman). Peary also brought his wife, Josephine, as a dietitian. Some newspapers criticized him for bringing her along.

On June 6, 1891, the group left New York on the ship SS Kite. In July, Peary broke his lower leg when the ship hit ice. He had to recover for six months at a camp called Red Cliff. Josephine stayed with him. The others hunted and learned about the area and the Inuit people.

Unlike many explorers before him, Peary studied Inuit survival methods. He built igloos and wore warm furs like the native people. This meant he didn't need to carry heavy tents or sleeping bags. Peary also relied on the Inuit as hunters and dog-drivers. He developed a system of using support teams and supply stops for Arctic travel, which he called the "Peary system." The Inuit visited Red Cliff, curious about the Americans. Josephine kept a journal about her experiences.

In 1891, Peary's leg healed by February 1892. In April 1892, he made short trips with Josephine and an Inuit driver to buy supplies. On May 3, 1892, Peary, Henson, Gibson, Cook, and Astrup began their main trek. After 150 miles, Peary continued with Astrup. They saw Independence Fjord from Navy Cliff and realized that Greenland was indeed an island. They traveled back to Red Cliff, covering a total of 1,250 miles.

Expeditions from 1898 to 1906

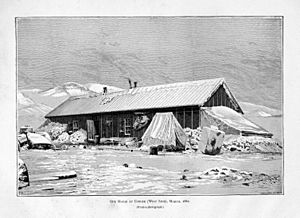

During his 1898–1902 expedition, Peary claimed to have seen "Jesup Land" west of Ellesmere Island. He said he saw Axel Heiberg Island before Norwegian explorer Otto Sverdrup. However, most experts do not agree with Peary's claim. The American Geographical Society and the Royal Geographical Society honored Peary for his hard work and mapping new areas. In 1900, he discovered Cape Morris Jesup at the northern tip of Greenland. In 1902, he reached a new "farthest north" point in the western hemisphere, north of Canada's Ellesmere Island.

Peary's next trip was supported by the Peary Arctic Club, which raised money for a new ship. The SS Roosevelt sailed through the ice between Greenland and Ellesmere Island. This ship reached the farthest north by ship in the American hemisphere. In 1906, Peary's dogsled journey for the pole started from Ellesmere Island. The teams moved slowly and then got separated by a storm.

Peary was left without anyone trained in navigation to confirm his journey. With little food, he made a quick dash and barely survived the melting ice. On April 20, he was no farther north than 86°30' latitude. He later claimed to have reached a new world record of 87°06' the next day. This meant he traveled at least 72 nautical miles without sleeping.

After returning to the Roosevelt, Peary explored west along Ellesmere's shore. He claimed to have seen a new land, "Crocker Land", on June 24, 1906. However, his diary from that time says, "No land visible." In 1914, another expedition found that Crocker Land did not exist. In December 1906, the National Geographic Society gave Peary its highest honor, the Hubbard Medal, for his 1905–1906 expedition.

Journey to the North Pole

On July 6, 1908, the Roosevelt left New York City with Peary's eighth Arctic expedition. There were 22 men, including the ship's master Robert Bartlett, surgeon Dr. J.W. Goodsell, and assistants Ross Gilmore Marvin, Donald Baxter MacMillan, George Borup, and Matthew Henson. They picked up several Inuit families in Greenland and spent the winter near Cape Sheridan on Ellesmere Island.

The expedition used Peary's system of support teams for the sled journey. Bartlett and three Inuit formed the first team. Borup and three Inuit formed the next team. Peary, with two Inuit, left on February 22. In total, there were 7 expedition members, 19 Inuit, 140 dogs, and 28 sledges.

As they moved north, different support teams turned back to the ship. On April 1, Bartlett's team turned back. Peary continued with five assistants: Henson, Ootah, Egigingwah, Seegloo, and Ooqueah. Only Henson was skilled enough to make navigation observations.

On April 6, 1909, Peary set up Camp Jesup. He claimed it was within 3 miles of the pole, based on his readings. Peary used a special tool called a sextant to measure the sun. He claimed to have taken many measurements. Peary stated that at some point during their travels, they had passed "over or very near the point where north and south and east and west blend into one." Henson went ahead and returned saying, "I think I'm the first man to sit on top of the world."

On April 7, 1909, Peary's group started their return journey. They reached Cape Columbia on April 23 and the Roosevelt on April 26. The Roosevelt sailed home on July 18.

When Peary returned, he learned that Dr. Frederick Cook, a surgeon from an earlier expedition, also claimed to have reached the North Pole in 1908. Despite some doubts, a committee from the National Geographic Society and the U.S. House of Representatives gave Peary credit for reaching the North Pole.

However, in 1988, explorer Wally Herbert looked at Peary's notebook again. He found it "lacking in essential data," which brought back doubts about Peary's claim.

Later Life and Legacy

Peary was promoted to captain in the Navy in October 1910. In March 1911, Congress thanked him for "reaching" the pole. He was also promoted to rear admiral and retired from the Navy on the same day. He moved to Eagle Island in Maine, which is now a historic site.

After retiring, Peary received many honors from science groups for his Arctic explorations. He was president of The Explorers Club twice. In 1916, Peary became chairman of the National Aerial Coast Patrol Commission. This group promoted using airplanes to find warships and submarines. This led to the creation of U.S. Navy Reserve air patrol units during World War I. After the war, Peary suggested a system of eight airmail routes, which helped start the U.S. Postal Service's airmail system.

Peary lived in Washington, D.C. until his death on February 20, 1920. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Matthew Henson was later re-interred near him in 1988.

Family Life

On August 11, 1888, Peary married Josephine Diebitsch. She was a smart woman who believed women should do more than just be mothers. Josephine worked at the Smithsonian Institution before marrying Peary.

The couple had two children: Marie Ahnighito (born 1893) and Robert Peary, Jr. Marie wrote children's books about Arctic adventures. As an explorer, Peary was often away for years. In their first 23 years of marriage, he spent only three years with his wife and family.

Both Peary and his assistant, Henson, had relationships with Inuit women and had children with them. Peary had at least two children with an Inuit woman named Aleqasina. In 1986, a professor named S. Allen Counter found Peary's son Kali and Henson's son Anaukaq, who were both in their eighties. Counter arranged for them and their families to visit the United States and meet their American relatives. He wrote a book about this in 1991, called North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo.

Peary and the Inuit People

Peary has been criticized for how he treated the Inuit people. He had children with Aleqasina. He also brought a small group of Inughuit Greenlandic Inuit to the United States. He took the Cape York meteorite, which was very important to the Inuit for making tools, and sold it for $40,000 in 1897.

An anthropologist named Franz Boas asked Peary to bring an Inuit person for study. During his trip to get the meteorite, Peary convinced six Inuit, including a man named Qisuk and his son Minik, to come to America. He promised they could return with tools and gifts within a year. Peary left them at the museum, where they lived in conditions very different from their homeland. Sadly, within a few months, four of them died from illness. Qisuk's bones were put on display after Minik was shown a fake burial.

Peary eventually helped Minik go home in 1909. Some believe this was to avoid bad publicity before Peary's big return after claiming to reach the North Pole.

Honors and Memorials

Many things have been named after Robert Peary:

- Several United States Navy ships, like the USS Robert E. Peary.

- The Peary–MacMillan Arctic Museum at Bowdoin College.

- Peary Land, Peary Glacier, Peary Nunatak, and Cape Peary in Greenland.

- Peary Bay and Peary Channel in Canada.

- Mount Peary in Antarctica.

- The lunar crater Peary at the moon's north pole.

- Camp Peary in Virginia, a training facility.

- Admiral Peary Vocational Technical School in Pennsylvania.

- A section of U.S. Route 22 in Pennsylvania, called the Admiral Peary Highway.

In 1986, the United States Postal Service issued a 22-cent postage stamp honoring both Peary and Henson.

Major General Adolphus Greely, another explorer, noted that Peary bravely risked his life traveling far from land. He reached areas close to the pole. However, Greely later doubted that Peary reached the exact North Pole.

Polar historian Fergus Fleming described Peary as "undoubtedly the most driven, possibly the most successful and probably the most unpleasant man in the annals of polar exploration."

In 1932, Peary's daughter, Marie Ahnighito Peary Stafford, helped place a monument to Peary at Cape York, Greenland.

Awards and Recognition

Peary received many medals and honors:

- Cullum Geographical Medal (1896)

- Charles P. Daly Medal (1902)

- Hubbard Medal (1906)

- Special great gold medals from the Royal Geographical Society of London and the National Geographic Society.

- Gold medals from other geographical societies around the world.

- Spanish Campaign Medal

- Honorary degrees from Bowdoin College and Edinburgh University.

- Honorary memberships in several societies.

- Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour (1913).

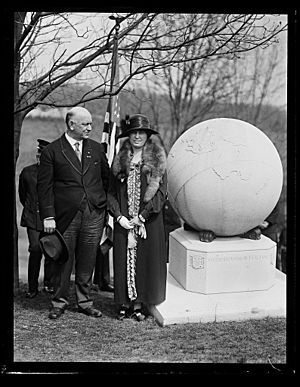

On April 6, 1922, the Admiral Robert Edwin Peary monument was unveiled at Arlington National Cemetery. Many important people, including President Harding, were there.

Images for kids

-

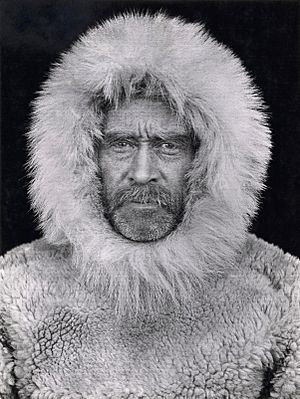

At Cape Sheridan on Ellesmere Island, 1909

-

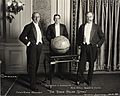

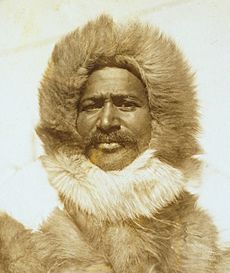

Matthew Henson, Peary's assistant, in 1910

-

Peary used abandoned Fort Conger on Ellesmere Island during his 1898–1902 expedition

-

Roosevelt in the Hudson–Fulton parade in 1909

-

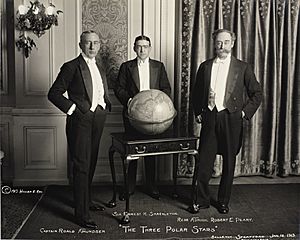

Amundsen, Shackleton, and Peary, in January 1913

-

Edwin Denby and Peary's daughter at grave, Arlington National Cemetery, April 6, 1922

-

Josephine Diebitsch in 1892

-

A Narwhal tusk lance with an iron head made from the Cape York meteorite.

-

Minik, one of the Inuit whom Peary took back to America for study.

See also

In Spanish: Robert Peary para niños

In Spanish: Robert Peary para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |