Frederick Cook facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Frederick Cook

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Fredrick Albert Cook

June 10, 1865 Hortonville, New York, U.S.

|

| Died | August 5, 1940 (aged 75) New Rochelle, New York, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Cemetery |

| Education | Columbia University |

| Spouse(s) |

|

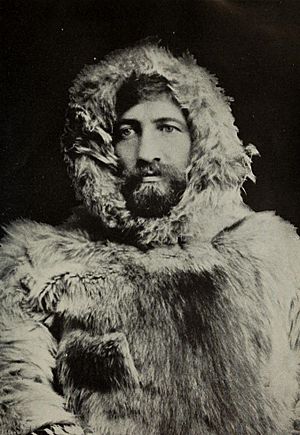

Frederick Albert Cook (born June 10, 1865 – died August 5, 1940) was an American explorer and doctor. He became famous for claiming to have reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908. This was almost a year before Robert Peary made a similar claim on April 6, 1909. Both of their claims have been debated ever since. Cook's expedition also discovered Meighen Island, which was the only island found in the North American Arctic by an American expedition.

In December 1909, a group from the University of Copenhagen looked at Cook's notes. They decided his claim to have reached the North Pole could not be proven. In 1911, Cook wrote a book about his journey, still saying he reached the Pole. His claim of being the first to climb Denali (Mount McKinley) in Alaska has also been questioned.

Contents

Frederick Cook's Life Story

Cook was born in Hortonville, New York. His parents, Theodor and Magdalena Koch, were German immigrants. They changed their last name to Cook. He went to local schools and later studied at Columbia University. He then went to New York University Medical School and became a doctor in 1890.

Cook married Libby Forbes in 1889, but she passed away two years later. In 1902, he married Marie Fidele Hunt. They had two daughters together. They later divorced in 1923.

Early Adventures and Expeditions

Cook worked as a surgeon on Robert Peary's Arctic trip in 1891–1892. He also joined the Belgian Antarctic Expedition from 1897–1899. During the Antarctic trip, their ship, the Belgica, got stuck in ice for the winter. Cook helped save the crew's lives by hunting for fresh meat. This stopped them from getting scurvy, a serious illness. This was the first time an expedition spent a winter in the Antarctic.

In 1897, Cook visited Tierra del Fuego twice. There, he met a missionary named Thomas Bridges. Cook studied the Ona and Yahgan native groups with Bridges. Bridges had written a dictionary of their language. Cook borrowed this important book but did not return it before Bridges died. Years later, Cook tried to publish the dictionary as his own work.

Climbing Denali's Peak

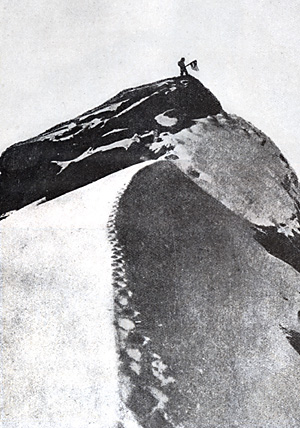

In 1903, Cook led a trip around Denali, North America's highest mountain. He went back in 1906 and claimed he was the first to reach its top with one other person. Other team members, like Belmore Browne, doubted his claim right away. But these doubts were not made public until 1909. This was when the argument with Peary about the North Pole started. Peary's supporters then said Cook's Denali climb was also fake.

Unlike later climbers, Cook did not take photos from the very top of Denali. His photo, which he said was from the summit, was actually taken on a small hill called Fake Peak. This hill was about 19 kilometers (12 miles) away from Denali's true summit.

In late 1909, Ed Barrill, who was with Cook on the 1906 climb, signed a paper saying they had not reached the top. Later, historians found that Peary's supporters had paid Barrill to say this. Before this, Barrill had always said they reached the summit. His 1909 paper included a map showing where "Fake Peak" was. It also showed that he and Cook had turned back far from Denali's top.

A climber named Bradford Washburn later studied Cook's 1906 claim. He took new photos from the same spots Cook had photographed. Between 1956 and 1995, Washburn showed that none of Cook's photos were taken near the summit. Cook's maps and descriptions of the summit also did not match the actual mountain. However, in the 1970s, a climber found a route that matched Cook's story. This route was successfully climbed by Russian mountaineers in 2005 and 2006.

Still, there is no real proof that Cook traveled between the "Gateway" and the summit. His photos, maps, and notes do not support his claim of reaching the top.

Journey to the North Pole

After his Denali trip, Cook went back to the Arctic in 1907. He planned to try to reach the North Pole. He started from Annoatok, a small village in northern Greenland, in February 1908. Cook said he reached the Pole on April 21, 1908. He traveled north from Axel Heiberg Island with two Inuit men, Ahpellah and Etukishook. On their way back south, he claimed they were blocked by open water. They had to live by hunting and ended up on Devon Island. From there, they traveled north again, reaching Annoatok in the spring of 1909. They said they nearly starved during this long journey.

Cook and his two companions were away for 14 months. Where they were during this time is still a big debate. Some historians believe Cook's story of traveling around the Arctic islands is true. Others point to later stories told by Cook's companions that seem different.

There are some interesting similarities between the route the two Inuit drew and a fictional journey in Jules Verne's novel The Adventures of Captain Hatteras. Both routes went over the "Pole of Cold" and the same wintering spot. Both expeditions also went to the same area in Jones Sound hoping to find a whaling ship.

At first, many people believed Cook's claim. But his rival, Robert Peary, who claimed to reach the North Pole in April 1909, challenged him. Peary and his supporters worked hard to make people doubt Cook.

Cook never showed detailed original maps or notes to prove he reached the North Pole. He said his important records were in three boxes. He left these boxes in Annoatok with Harry Whitney, an American hunter. When Whitney tried to take the boxes on Peary's ship, Peary would not allow it. So, Whitney left the boxes hidden in Greenland, and they were never found.

On December 21, 1909, a group at the University of Copenhagen looked at Cook's evidence. They decided his records did not prove he reached the Pole. (Peary refused to let his own records be checked by a third party.)

Cook sometimes said he had copies of his navigation data. He published some in 1911, but they had a mistake in them. Ahwelah and Etukishook, Cook's Inuit companions, gave different stories about where they went with him. However, with better maps today, many of these differences can be understood. Whitney believed they reached the North Pole with Cook but did not want to get involved in the argument.

Peary's team claimed that Ahwelah and Etukishook told them they only traveled a few days from land. However, a map supposedly drawn by Ahwelaw and Etukishook correctly showed Meighen Island. This strongly suggests they visited it as they claimed. Later, explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson landed on Meighen Island in 1916. He read Cook's papers and agreed that Cook had discovered the island. It is the only island found by an American expedition in the North American Arctic.

The arguments between Cook and Peary made Roald Amundsen very careful. When he went to the South Pole, he took many steps to make sure there would be no doubt about his success. Amundsen also had the advantage of traveling over land. He left clear proof at the South Pole. Any ice Cook might have camped on would have drifted far away in a year.

At the end of his 1911 book, Cook wrote: "I have stated my case, presented my proofs. As to the relative merits of my claim, and Mr. Peary's, place the two records side by side. Compare them. I shall be satisfied with your decision."

Cook's Public Standing

Cook's reputation never fully recovered from the attacks on his claims. While Peary's North Pole claim was accepted for many years, it has since been questioned by many, including the National Geographic Society. Cook spent years defending his claims and threatening to sue writers who said he had faked his trips.

Writer Robert Bryce studied the complex story of Cook and Peary. He believes Cook, as a doctor and explorer, cared about the people on his trips and admired the Inuit. Bryce wrote that Cook "genuinely loved and hungered for the real meat of exploration—mapping new routes and shorelines, learning and adapting to the survival techniques of the Eskimos, advancing his own knowledge—and that of the world—for its own sake." However, he needed a more exciting goal to get money for his expeditions. There was a lot of pressure on explorers to be the first to reach the Pole to get funding.

Legal Challenges

In 1919, Cook began promoting new oil companies in Fort Worth, Texas. In 1923, Cook and other oil promoters faced legal issues related to their business dealings. Cook said he was innocent and went to trial. The jury found Cook guilty of fraud. In November 1923, Cook was sentenced to prison.

Later Life

Cook was in prison until 1930. Roald Amundsen, who felt Cook had saved his life on the Belgica expedition, visited him several times. Cook was given a pardon by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940. This was ten years after his release and shortly before he died on August 5. He was buried at the Chapel of Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo.

Popular Culture

- The Navigator of New York (2003) – A novel by Wayne Johnston

- La jaula de los onas (2021) - A novel by Carlos Gamerro

See also

In Spanish: Frederick Cook para niños

In Spanish: Frederick Cook para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |