Warren G. Harding facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Warren G. Harding

|

|

|---|---|

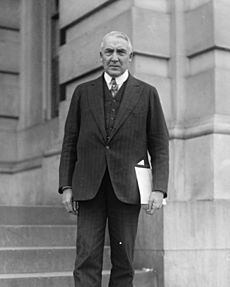

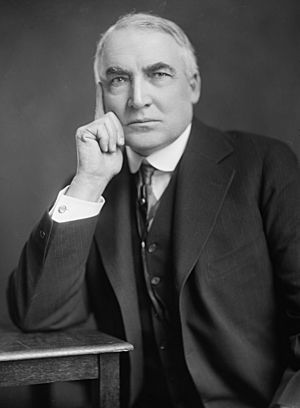

Portrait by Harris & Ewing, c. 1920

|

|

| 29th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1921 – August 2, 1923 |

|

| Vice President | Calvin Coolidge |

| Preceded by | Woodrow Wilson |

| Succeeded by | Calvin Coolidge |

| United States Senator from Ohio |

|

| In office March 4, 1915 – January 13, 1921 |

|

| Preceded by | Theodore E. Burton |

| Succeeded by | Frank B. Willis |

| 28th Lieutenant Governor of Ohio | |

| In office January 11, 1904 – January 8, 1906 |

|

| Governor | Myron T. Herrick |

| Preceded by | Harry L. Gordon |

| Succeeded by | Andrew L. Harris |

| Member of the Ohio Senate from the 13th district |

|

| In office January 1, 1900 – January 4, 1904 |

|

| Preceded by | Henry May |

| Succeeded by | Samuel H. West |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Warren Gamaliel Harding

November 2, 1865 Blooming Grove, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | August 2, 1923 (aged 57) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Harding Tomb |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Elizabeth (by Nan Britton) |

| Parent |

|

| Education | Ohio Central College (BA) |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

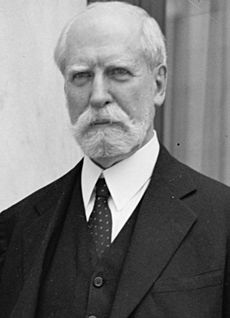

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States. He served from 1921 until his death in 1923. Harding was a member of the Republican Party. He was one of the most liked U.S. presidents during his time in office. After his death, some of his team were involved in scandals, which sadly affected how people remembered him.

Harding lived in rural Ohio for most of his life. He only left when political work took him elsewhere. As a young man, he bought The Marion Star newspaper. He made it very successful. Harding served in the Ohio State Senate from 1900 to 1904. He was also lieutenant governor for two years. He lost the election for governor in 1910. However, he was elected to the United States Senate in 1914. This was Ohio's first direct election for that office.

Harding ran for president in 1920. Many thought he had little chance before the convention. When the main candidates could not get enough votes, the convention was stuck. Support for Harding grew, and he was chosen on the tenth vote. He ran a "front porch campaign". He stayed mostly in Marion and let people come to him. He promised a "return to normalcy" like before World War I. He won by a lot in the election. He beat Democrat James M. Cox. Harding became the first sitting senator to be elected president.

Harding chose many respected people for his cabinet. These included Andrew Mellon for Treasury. He also picked Herbert Hoover for Commerce. Charles Evans Hughes was chosen for the State Department. A big success in foreign policy was the Washington Naval Conference in 1921–1922. At this meeting, the world's main naval powers agreed to limit their navies for ten years. Harding also released political prisoners. These were people arrested for being against World War I. In 1923, Harding died of a heart attack in San Francisco. This happened during a trip to the western U.S. Vice President Calvin Coolidge became president after him.

Harding's Interior Secretary, Albert B. Fall, and his Attorney General, Harry Daugherty, were later tried for corruption. Fall was found guilty, but Daugherty was not. These events greatly harmed Harding's reputation after his death. He is often seen as one of the less successful presidents in U.S. history.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Childhood and School Days

Warren Harding was born on November 2, 1865. His birthplace was Blooming Grove, Ohio. As a small child, he was called "Winnie." He was the oldest of eight children. His parents were George Tryon Harding and Phoebe Elizabeth Harding. Phoebe was a licensed midwife. Tryon farmed and taught school. He later became a doctor.

In 1870, the Harding family moved to Caledonia, Ohio. There, Tryon bought The Argus, a local newspaper. From age 11, Harding learned about the newspaper business. In 1879, at age 14, Harding went to Ohio Central College. This was his father's old school. He was a good student. He and a friend made a small newspaper for the college and town. In 1882, he joined his family in Marion, Ohio after graduating.

Becoming a Newspaper Editor

When Harding was young, most people lived on farms. They also lived in small towns. He spent much of his life in Marion. It was a small city in central Ohio. He loved Marion and its way of life.

After college, Harding worked as a teacher and an insurance man. He also tried studying law briefly. Then, he and some partners bought The Marion Star. It was a struggling newspaper. Harding was 18 years old. He used a railroad pass that came with the paper. He went to the 1884 Republican National Convention. There, he met famous journalists. He supported James G. Blaine for president.

Harding returned to find the paper taken back by the sheriff. This was because of unpaid debts. During the election, Harding worked for another paper. He had to praise the Democratic candidate, Grover Cleveland. Cleveland won the election. Later, with his father's help, Harding bought back The Marion Star.

Through the late 1880s, Harding built up the Star. Marion usually voted Republican. However, Marion County was Democratic. So, Harding made the Star nonpartisan. He also had a weekly edition that was moderately Republican. This plan brought in advertisers. It also put the town's Republican weekly paper out of business.

Marion's population grew a lot. This helped the Star. Harding worked hard to promote the city. He invested in many local businesses. He became a successful investor. He had a lot of money by 1923. Harding used his newspaper to get involved in local public business. He is the only U.S. president who worked full-time as a journalist.

Marriage and Family Life

Harding first met Florence Kling. She was the daughter of a local banker, Amos Kling. Harding often criticized Amos in his newspaper. Florence was very involved in her father's business. She was as strong-willed as her father. Florence Kling and her father had disagreements. She later divorced her first husband. She returned to Marion with her young son. Florence became a piano teacher. One of her students was Harding's sister. By 1886, Florence and Harding were dating.

Amos Kling did not approve of their relationship. He spread rumors about Harding's family. He also told local businesses to avoid Harding's paper. Harding warned him to stop.

Warren and Florence were married on July 8, 1891. They got married at their new home in Marion. They had designed the house together. They did not have any children. Harding lovingly called his wife "the Duchess." This was after a character in a newspaper story. Florence Harding became very involved in her husband's career. She helped make the Star profitable. She managed the paper's circulation department. Many believe she helped Harding achieve more than he could have alone. Some even say she helped him reach the White House.

First Steps in Politics

Soon after buying the Star, Harding got into politics. He supported Joseph B. Foraker for governor in 1885. Foraker was a new leader in Ohio Republican politics. Harding was always loyal to his party. He supported Foraker in the state's complex politics. Harding was a delegate to the Republican state convention in 1888. He was only 22. He was often chosen as a delegate until he became president.

Harding's work as an editor affected his health. From age 23 to 35, he had to go to the Battle Creek Sanitarium five times. These visits were for tiredness and stress. These problems were early signs of the heart condition that later caused his death. During one absence in 1894, Florence Harding took over his business manager role. She became his main helper at the Star. She kept this role until they moved to Washington in 1915. Her skills allowed Harding to travel and give speeches. Florence was very careful with money. She believed Harding did well when he listened to her.

In 1892, Harding visited Washington. He met Democratic Congressman William Jennings Bryan. He also went to Chicago's World's Columbian Exposition in 1893. In 1895, Harding lost an election for county auditor. However, he did better than expected. The next year, Harding gave speeches across Ohio. He supported Republican presidential candidate William McKinley. Harding started to become well-known throughout Ohio.

Rising Politician (1897–1919)

Ohio State Senator

Harding tried again for elected office. He admired Senator Foraker. He also had good relations with Senator Mark Hanna. Hanna was McKinley's political manager. With their support, Harding ran for state Senate in 1899. He won easily for a two-year term.

Harding started as an unknown in the state senate. But he became very popular in the Ohio Republican Party. He was calm and humble. These traits made other Republicans like him. Legislative leaders asked him for advice on tough problems. State senators in Ohio usually served only one term. But Harding was chosen again in 1901. After McKinley's death in September, Harding won a second term. He more than doubled his winning margin.

Harding accepted some benefits for political favors. This was common for politicians at the time. He likely did not think there was anything wrong with it. These favors seemed like normal rewards for party service.

Soon after Harding's first election, he met Harry M. Daugherty. Daugherty became a very important person in Harding's political life. Daugherty was a lobbyist in Columbus. After meeting Harding, Daugherty said, "Gee, what a great-looking President he'd make."

Ohio State Leader

In early 1903, Harding said he would run for Governor of Ohio. But party leaders thought he could not win. They persuaded Cleveland banker Myron T. Herrick to run instead. Harding then sought to be lieutenant governor. Both Herrick and Harding were chosen without opposition. Foraker and Hanna campaigned for them. Herrick and Harding won by a lot.

Herrick made some bad choices as governor. These turned important Republican groups against him. Harding, on the other hand, had little to do. He did his job very well. He presided over the state Senate. This helped him meet more political contacts. Harding hoped to run for governor in 1905. But Herrick refused to step aside. Harding then said he would not seek any office in 1905. Herrick lost the election. But his new running mate, Andrew L. Harris, won. Harris became governor after the death of the Democrat John M. Pattison.

In 1908, Ohio voters chose legislators. These legislators would decide if Foraker would be re-elected. Foraker had argued with President Roosevelt. Harding's Star newspaper first supported Foraker. It criticized Roosevelt. But then Harding changed his mind. He declared for Taft. This helped Harding's career. He was also popular with the more progressive Republicans.

Harding ran for governor again in 1910. He won the Republican nomination. But the party was divided. They could not beat the united Democrats. He lost the election to Judson Harmon. Harry Daugherty managed Harding's campaign. Harding did not blame Daugherty for the loss. President Taft and former president Roosevelt campaigned for Harding. But their arguments split the Republican Party. This helped Harding lose.

The party split grew. In 1912, Taft and Roosevelt were rivals. The 1912 Republican National Convention was very divided. Taft asked Harding to give a speech nominating him. But the delegates were angry. Taft was chosen again. But Roosevelt's supporters left the party. Harding, as a loyal Republican, supported Taft. The Republican vote was split. This allowed the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson, to win.

Becoming a U.S. Senator

Election of 1914

Congressman Theodore E. Burton was a senator. He said he would seek a second term in 1914. By this time, the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed. It gave people the right to elect senators. Ohio also started using primary elections for the office. Foraker and former congressman Ralph D. Cole also ran. When Burton left the race, Foraker was the favorite. But his old-style Republicanism seemed outdated. Harding was asked to join the race. Daugherty said he pushed Harding to run. Harding ran a very friendly campaign. He tried not to offend anyone. Harding won the primary by 12,000 votes over Foraker.

Harding's opponent in the general election was Ohio Attorney General Timothy Hogan. Hogan had become well-known despite some prejudice against Roman Catholics. In 1914, World War I started. The idea of a Catholic senator from Ohio increased anti-immigrant feelings. Some papers warned that Hogan was part of a plot. Harding did not attack Hogan, who was an old friend. He also did not speak out against the hatred for his opponent.

Harding's friendly campaign style worked well. One friend called his speeches a mix of "platitudes, patriotism, and pure nonsense." Harding used his speeches to get elected. He made as few enemies as possible. Harding won by over 100,000 votes. A Republican governor, Frank B. Willis, also won.

Junior Senator in Washington

When Harding joined the U.S. Senate, Democrats controlled Congress. President Wilson led them. As a new senator in the minority party, Harding got less important committee jobs. But he did these duties carefully. He was a safe, conservative Republican voter. Like in the Ohio Senate, Harding became widely liked.

Harding was respected by both Republicans and Progressives. He was asked to be temporary chairman of the 1916 Republican National Convention. He also gave the main speech. He told delegates to be a united party. The convention chose Justice Charles Evans Hughes. Harding reached out to Roosevelt. Roosevelt had refused the 1916 Progressive nomination. This ended that party. In the November 1916 election, Hughes lost to Wilson by a small margin.

Harding spoke and voted for the war resolution in April 1917. This put the U.S. into World War I. In August, Harding said Wilson should have almost total power during wartime. Harding voted for most war laws. This included the Espionage Act of 1917, which limited civil liberties. But he was against the excess profits tax. In May 1918, Harding was less supportive of Wilson. He opposed a bill to expand the president's powers.

In the 1918 elections, Republicans took control of the Senate. This happened just before the war ended. Harding was appointed to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Wilson did not take any senators with him to the Paris Peace Conference. He thought he could get the Treaty of Versailles approved by appealing to the people. When he returned with a treaty for peace and a League of Nations, most people supported him. Many senators disliked Article X of the League Covenant. This part said members had to defend any attacked nation. Senators saw this as forcing the U.S. into war without Congress's approval. Harding was one of 39 senators who signed a letter against the League.

Wilson invited the Foreign Relations Committee to the White House. They discussed the treaty informally. Harding questioned Wilson well about Article X. The president avoided his questions. The Senate debated the treaty in September 1919. Harding gave a major speech against it. By then, Wilson had a stroke. With a sick president and less public support, the treaty was defeated.

Presidential Election of 1920

Primary Campaign

Most Progressives had rejoined the Republican Party. Their former leader, Theodore Roosevelt, was the top choice for the 1920 Republican presidential nomination. But Roosevelt died suddenly on January 6, 1919. Many candidates quickly appeared. These included General Leonard Wood, Illinois Governor Frank Lowden, and California Senator Hiram Johnson. Others were Herbert Hoover and Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge.

Harding wanted to be president. He also wanted to keep control of Ohio Republican politics. This would help him get re-elected to the Senate in 1920. On December 17, 1919, Harding announced he was running for president. Leading Republicans did not like Wood or Johnson. They were from the progressive part of the party. Lowden was also seen as not much better. Harding was more acceptable to the older party leaders.

Daugherty became Harding's campaign manager. He was sure no other candidate could get enough votes. His plan was to make Harding an acceptable choice once the main candidates failed. Daugherty set up a "Harding for President" office in Washington. He also managed a group of Harding's friends and supporters. Harding tried to get support by writing many letters.

In 1920, there were only 16 presidential primary states. Ohio was the most important for Harding. He needed loyal supporters at the convention. The Wood campaign hoped to beat Harding in Ohio. Wood campaigned there. His supporter, Procter, spent a lot of money. Harding spoke in his usual friendly style. He and Daugherty were sure they would win Ohio's 48 delegates. Harding went to Indiana before the April 27 Ohio primary. Harding won Ohio by only 15,000 votes over Wood. He got less than half the total vote. He won only 39 of 48 delegates. In Indiana, Harding finished fourth. He failed to win any delegates. He was ready to give up. But Florence Harding stopped him. She told him to keep fighting until the convention was over.

After the poor results, Harding went to Boston. He gave a speech that became famous. He said, "America's present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration;..." Harding understood what the nation wanted.

The Convention in Chicago

The 1920 Republican National Convention started on June 8, 1920. It was in Chicago. The delegates were very divided. A recent report on campaign spending had just come out. It showed Wood had spent $1.8 million. This supported claims that Wood was trying to buy the presidency. Some of the money Lowden spent went to delegates. Johnson had spent $194,000, and Harding $113,000. Many delegates thought Johnson was behind the investigation. This made the Lowden and Wood groups angry. It ended any chance of a compromise among the main candidates. Of almost 1,000 delegates, 27 were women. The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, giving women the right to vote, was almost ratified. It passed before the end of August. The convention had no single leader. Most delegates voted as they wished.

Reporters thought Harding was unlikely to be chosen. They saw him as a "dark horse" candidate. Harding was in Chicago, watching his campaign. He had finished sixth in the last public opinion poll.

Nominations for president began on June 11. Harding had asked Willis to nominate him. Willis gave a speech that delegates liked. It was friendly and short in the Chicago heat. Willis asked, "Say, boys—and girls too—why not name Warren Harding?" The laughter and applause made people feel good about Harding.

Four votes were taken on June 11. They showed no clear winner. Wood had the most votes, but not enough to win. Harding had only 651⁄2 votes. The chairman stopped the convention for the night.

The night of June 11–12, 1920, became famous. It was called the "smoke-filled room" night. Legend says party leaders agreed to make Harding the nominee. Historians have looked at a meeting in the suite of RNC Chairman Will H. Hays. Senators and others came and went. Many possible candidates were discussed. Utah Senator Reed Smoot supported Harding. He said if Democrats chose Cox, Republicans should pick Harding to win Ohio. Smoot told The New York Times there was an agreement to nominate Harding. But this was not true. Many people supported Harding, but there was no firm plan. Two others at the meeting predicted Harding would be nominated. This was because of the problems with other candidates.

Morning newspapers suggested a secret plan. Historian Wesley M. Bagby wrote that different groups worked separately. They all wanted to nominate Harding. Bagby said the main reason Harding was chosen was his popularity. He was popular among the regular delegates.

The delegates heard rumors that senators had chosen Harding. This was not true, but delegates believed it. They started voting for Harding. When voting began on June 12, Harding gained votes. He rose to 1331⁄2 votes. The two main candidates stayed about the same. The chairman then called a three-hour break. Daugherty was very angry. He argued with the chairman. The break was used to try to stop Harding's momentum. They tried to make RNC Chairman Hays the nominee. But Hays refused. On the ninth vote, delegations started switching to Harding. He took the lead with 3741⁄2 votes. Wood had 249, and Lowden 1211⁄2. Lowden released his delegates to Harding. The tenth vote was just a formality. Harding finished with 6721⁄5 votes. Wood had 156. The nomination was made official. Delegates wanted to leave town. They then chose the vice president. Harding wanted Senator Irvine Lenroot. But Lenroot did not want to run. An Oregon delegate then suggested Governor Coolidge. The delegates cheered. Coolidge was popular for his role in ending the Boston Police Strike of 1919. He was nominated for vice president.

General Election Campaign

Republican newspapers quickly supported the Harding/Coolidge ticket. But other newspapers were disappointed. The New York World said Harding was the least qualified candidate since James Buchanan. They called him "weak and mediocre." The Hearst newspapers called Harding "the flag-bearer of a new Senatorial autocracy." The New York Times called him "a very respectable Ohio politician of the second class."

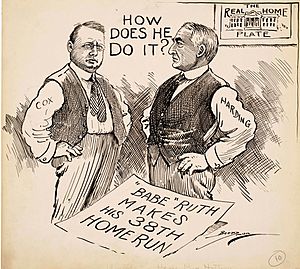

The Democratic National Convention opened in San Francisco on June 28, 1920. Woodrow Wilson wanted to be nominated for a third term. But delegates believed Wilson's health was too poor. They looked for another candidate. Former Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo was a top contender. But he was Wilson's son-in-law. He refused to be nominated if the president wanted it. Many voted for McAdoo anyway. This led to a deadlock with Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. On the 44th vote, Democrats chose Governor Cox for president. His running mate was Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. Both Cox and Harding owned newspapers. This meant two Ohio editors were running for president. Some complained there was no real political choice. Both Cox and Harding were careful with money.

Harding decided to run a "front porch campaign." This was like McKinley in 1896. Harding had changed his front porch to look like McKinley's. This showed he wanted to be president. Harding stayed home in Marion. He gave speeches to visiting groups. Meanwhile, Cox and Roosevelt traveled the country. They gave hundreds of speeches. Coolidge spoke in the Northeast and South. He was not a major factor in the election.

In Marion, Harding ran his campaign. As a newspaper man, he got along well with the press. His "return to normalcy" idea was helped by Marion's calm atmosphere. It made many voters feel nostalgic. The front porch campaign helped Harding avoid mistakes. As the election got closer, he became stronger. The Democratic candidates' travels eventually made Harding take some short speaking trips. But mostly, he stayed in Marion. Harding argued that America did not need another Wilson. He asked for a president who was "near the normal."

Harding's vague speeches bothered some people. McAdoo said a typical Harding speech was "an army of pompous phrases moving over the landscape in search of an idea." The New York Times saw Harding's speeches more positively. They said most people could find "a reflection of their own indeterminate thoughts" in them.

Wilson had said the 1920 election would be about the League of Nations. This made it hard for Cox to change his stance. Roosevelt strongly supported the League. But Cox was less excited. Harding was against joining the League of Nations as Wilson had planned. But he favored an "association of nations." This would be based on the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague. This was general enough to satisfy most Republicans. Only a few left the party over this issue. By October, Cox realized many people were against Article X. He said changes to the treaty might be needed. This shift allowed Harding to say no more on the topic.

The Republican National Committee hired Albert Lasker. He was an advertising executive. Lasker launched a big advertising campaign for Harding. It used many new advertising methods for the first time in a presidential campaign. This included newsreels and sound recordings. Visitors to Marion took photos with Senator and Mrs. Harding. Copies were sent to their local newspapers. Billboards, newspapers, and magazines were used. People also made phone calls with scripts to promote Harding.

During the campaign, opponents spread old rumors. They said Harding's ancestors were African American. Harding's campaign manager denied these claims. A professor named William Estabrook Chancellor spread the rumors.

By Election Day, November 2, 1920, most people knew Republicans would win. Harding received 60.2 percent of the popular vote. This was the highest percentage since the two-party system began. He also got 404 electoral votes. Cox received 34 percent of the national vote and 127 electoral votes. Socialist Eugene V. Debs was in prison for opposing the war. He still received 3 percent of the national vote. Republicans greatly increased their majority in Congress.

Presidency (1921–1923)

Starting as President

Harding was sworn in on March 4, 1921. His wife and father were there. Harding wanted a simple inauguration. There was no big parade. Only the swearing-in and a short reception happened. In his first speech, he said, "Our most dangerous tendency is to expect too much from the government and at the same time do too little for it."

After the election, Harding said he was going on vacation. He would not make decisions about appointments until December. He went to Texas to fish and play golf. Then he went to the Panama Canal Zone. He went to Washington when Congress opened in December. He was welcomed as a hero. He was the first sitting senator elected president. Back in Ohio, he planned to ask the "best minds" for advice on appointments.

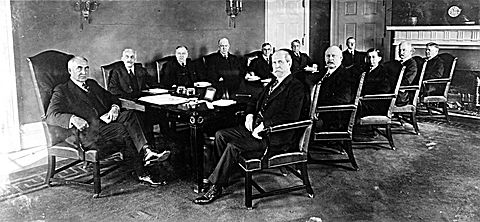

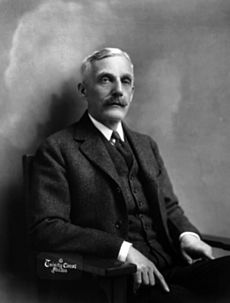

Harding chose Charles Evans Hughes as his Secretary of State. Hughes was a former justice. Harding ignored advice from others. He chose Pittsburgh banker Andrew W. Mellon for Treasury. Mellon was one of the richest people in the country. He appointed Herbert Hoover as Secretary of Commerce. RNC Chairman Will Hays became Postmaster General. This was a cabinet job then. He left after a year to work in the movie industry.

Two of Harding's cabinet choices later harmed his administration's reputation. These were his Senate friend, Albert B. Fall, the Interior Secretary. The other was Daugherty, the Attorney General. Fall was a rancher and former miner. He supported development. Conservationists like Gifford Pinchot were against him. The New York Times made fun of Daugherty's appointment. They said Harding chose a "best friend" instead of a "best mind." Historians Trani and Wilson said the choice made sense then. Daugherty was a good lawyer. He knew about politics. He was a good problem-solver and someone Harding could trust.

| The Harding Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Warren G. Harding | 1921–1923 |

| Vice President | Calvin Coolidge | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of State | Charles Evans Hughes | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of Treasury | Andrew Mellon | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of War | John W. Weeks | 1921–1923 |

| Attorney General | Harry M. Daugherty | 1921–1923 |

| Postmaster General | Will H. Hays | 1921–1922 |

| Hubert Work | 1922–1923 | |

| Harry Stewart New | 1923 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Edwin Denby | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Albert B. Fall | 1921–1923 |

| Hubert Work | 1923 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Henry Cantwell Wallace | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of Commerce | Herbert Hoover | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of Labor | James J. Davis | 1921–1923 |

Foreign Policy and World Relations

Ending the War and European Ties

Harding made it clear that Hughes, his Secretary of State, would handle foreign policy. This was different from Wilson, who managed international affairs himself. Hughes had to follow some general rules. After taking office, Harding decided the U.S. would not join the League of Nations. The Treaty of Versailles was not approved by the Senate. So, the U.S. was still technically at war with Germany, Austria, and Hungary. Peace began with the Knox–Porter Resolution. This declared the U.S. at peace. Treaties with Germany, Austria, and Hungary were approved in 1921. These treaties included many parts of the Treaty of Versailles, but not the League.

The U.S. still had to deal with the League. Hughes's State Department first ignored messages from the League. Or they tried to go around it by talking directly to member nations. By 1922, the U.S. was dealing with the League through its consul in Geneva. The U.S. did not join political meetings. But it sent observers to meetings about technical and humanitarian issues.

When Harding became president, foreign governments wanted to reduce their war debt to the U.S. Germany also wanted to reduce its war payments. The U.S. refused to consider a group settlement. Harding wanted a plan from Mellon to reduce war debts. But Congress passed a stricter bill in 1922. Hughes made a deal for Britain to pay its war debt over 62 years. This reduced the amount owed. This deal was approved by Congress in 1923. It became a model for talks with other nations. Talks with Germany led to the Dawes Plan in 1924.

Wilson had not solved the issue of U.S. policy towards Bolshevik Russia. The U.S. had sent troops there after the Russian Revolution. Wilson then refused to recognize the Russian SFSR. Harding's Commerce Secretary Hoover led the policy. When famine hit Russia in 1921, Hoover's American Relief Administration helped. They made a deal with the Russians to provide aid. Leaders of the U.S.S.R. hoped this would lead to recognition. Hoover supported trade with the Soviets. But Hughes was against it. The issue was not solved during Harding's presidency.

Harding wanted less military spending during his campaign. But it was not a main issue. He gave a speech to Congress in April 1921. He talked about his goals. He mentioned disarmament. He said the government should not forget the "call for reduced expenditure" on defense.

Idaho Senator William Borah suggested a conference. The main naval powers, the U.S., Britain, and Japan, would agree to cut their fleets. Harding agreed. After talks, representatives from nine nations met in Washington in November 1921. Most diplomats first went to Armistice Day ceremonies. Harding spoke at the burial of the Unknown Soldier of World War I. He said, "We know not whence he came, only that his death marks him with the everlasting glory of an American dying for his country."

Hughes spoke at the conference on November 12, 1921. He made the American proposal. The U.S. would stop building or remove 30 warships. Britain would do the same for 19 vessels, and Japan for 17. Hughes was largely successful. Agreements were made on this and other points. These included solving disputes over Pacific islands. They also limited the use of poison gas. The naval agreement only applied to battleships and some aircraft carriers. It did not stop future rearmament. Still, Harding and Hughes were praised by the press. Senator Lodge and Senator Oscar Underwood were part of the U.S. delegation. They helped get the treaties through the Senate.

The U.S. had many ships from World War I. Congress had allowed them to be sold in 1920. But the Senate would not approve Wilson's choices for the Shipping Board. Harding appointed Albert Lasker as chairman. Lasker tried to run the fleet profitably until it could be sold. Few ships could be sold for close to what the government paid. Lasker suggested a large payment to the merchant marine to help sales. Harding often asked Congress to approve it. The bill was not popular in the Midwest. It passed the House. But it was stopped by a filibuster in the Senate. Most government ships were eventually scrapped.

Latin American Relations

Intervention in Latin America was a minor campaign issue. Harding spoke against Wilson sending U.S. troops to the Dominican Republic and Haiti. He also criticized Franklin Roosevelt for his role in Haiti. Once Harding was president, Hughes worked to improve relations with Latin American countries. These countries were worried about the U.S. using the Monroe Doctrine to justify intervention. When Harding became president, U.S. troops were also in Cuba and Nicaragua. Troops in Cuba left in 1921. But U.S. forces stayed in Haiti and Nicaragua during Harding's presidency. In April 1921, Harding approved the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty with Colombia. This gave Colombia $25 million. It was a settlement for the U.S.-caused Panamanian revolution of 1903. Latin American nations were not fully happy. The U.S. refused to say it would stop intervening. But Hughes promised to limit it to nations near the Panama Canal. He also promised to make U.S. goals clear.

The U.S. had often intervened in Mexico under Wilson. It had also stopped recognizing Mexico diplomatically. The Mexican government wanted recognition before talks. But Wilson refused. Both Hughes and Fall were against recognition. Hughes sent a draft treaty to Mexico in May 1921. It included promises to pay Americans for losses in Mexico since the 1910 revolution. Mexico did not want to sign a treaty before being recognized. Mexico worked to improve relations with American businesses. It made deals with creditors. It also ran a public relations campaign in the U.S. This had an effect. By mid-1922, Fall had less influence. This reduced resistance to recognition. The two presidents appointed people to make a deal. The U.S. recognized the Mexican government on August 31, 1923. This was just under a month after Harding's death. It was largely on Mexico's terms.

Domestic Policies

Economic Recovery and Tax Cuts

When Harding took office on March 4, 1921, the nation was in a postwar economic downturn. Harding called a special session of Congress for April 11. The next day, he spoke to Congress. He asked for lower income taxes. He also wanted higher tariffs on farm goods to protect American farmers. He also supported highways, aviation, and radio. On May 27, Congress passed an emergency tariff increase on farm products. A law creating a Bureau of the Budget followed on June 10. Harding appointed Charles Dawes to lead it. Dawes was told to cut spending.

Treasury Secretary Mellon also suggested that Congress cut income tax rates. He wanted to end the corporate excess profits tax. The House committee supported Mellon's ideas. But some congressmen wanted to raise corporate tax rates. Harding was unsure what to support. He told a friend, "I can't make a thing out of this tax problem." Harding tried to find a middle ground. He got a bill passed in the House. In the Senate, the bill got mixed up with efforts to give World War I veterans a bonus. Harding spoke to the Senate on July 12. He asked them to pass the tax law without the bonus. The tax bill finally passed in November. It had higher rates than Mellon had wanted.

Harding was against the veterans' bonus. He said the nation was already doing a lot for them. He argued the bill would "break down our Treasury." The Senate sent the bonus bill back to committee. But the issue came back in December 1921. A bill for a bonus passed both houses in September 1922. But Harding's veto was barely upheld. A non-cash bonus for soldiers passed in 1924.

In his first annual message to Congress, Harding wanted the power to change tariff rates. The tariff bill became a fight among special interest groups. Harding signed the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act on September 21, 1922. He praised it only for giving him some power to change rates. Historians Trani and Wilson said the bill was "ill-considered." It caused problems in international trade. It also made paying war debts harder.

Mellon studied how tax rates affected money. He found that high income tax rates made money go hidden or abroad. He believed lower rates would bring in more tax money. Based on his advice, Harding's tax bill cut taxes starting in 1922. The highest tax rate was cut from 73% in 1921 to 25% in 1925. Taxes were also cut for lower incomes starting in 1923. These lower rates greatly increased money going to the treasury. They also led to a lot of deregulation. Federal spending as a share of the economy fell. By late 1922, the economy started to get better. Unemployment dropped from 12% in 1921 to 3.3% for the rest of the decade. Wages, profits, and productivity all grew a lot. The economy grew over 5% each year in the 1920s.

New Technologies and Progress

The 1920s were a time of new inventions in America. Electricity became more common. Making many cars helped other industries. These included highway building, rubber, steel, and construction. Hotels were built for tourists on the new roads. This economic boost helped the nation recover. To improve highways, Harding signed the Federal Highway Act of 1921. From 1921 to 1923, the government spent a lot of money on highways. This put a lot of money into the U.S. economy. In 1922, Harding said America was in the age of the "motor car." He said it showed "our standard of living and gauges the speed of our present-day life."

Harding wanted to regulate radio broadcasting. He said this in his April 1921 speech to Congress. Commerce Secretary Hoover led this project. He held a conference of radio broadcasters in 1922. This led to a voluntary agreement. It allowed licensing of radio frequencies through the Commerce Department. Both Harding and Hoover knew more than an agreement was needed. But Congress was slow to act. Radio regulation did not happen until 1927.

Harding also wanted to promote aviation. Hoover again took the lead. He held a national conference on commercial aviation. They talked about safety, plane inspections, and pilot licenses. Harding again pushed for laws. But nothing was done until 1926. That's when the Air Commerce Act created the Bureau of Aeronautics. It was part of Hoover's Commerce Department.

Business and Workers

Harding believed the government should help businesses as much as possible. He was suspicious of labor unions. He saw them as working against businesses. He tried to get them to work together. He called a conference on unemployment in September 1921. Harding said no federal money would be available. No major laws came from it. But some public works projects were sped up.

Harding let each cabinet secretary run their department. Hoover expanded the Commerce Department. He made it more helpful to businesses. This fit Hoover's belief that private companies should lead the economy. Harding greatly respected Hoover. He often asked for his advice. He called Hoover "the smartest 'gink' I know."

Many strikes happened in 1922. Workers wanted better wages and jobs. In April, 500,000 coal miners went on strike. They were led by John L. Lewis. Mining companies said times were hard. Lewis said they were trying to break the union. As the strike continued, Harding offered a compromise. Miners agreed to go back to work. Congress created a group to look into their complaints.

On July 1, 1922, 400,000 railroad workers went on strike. Harding suggested a deal. It made some concessions. But management did not agree. Attorney General Daugherty got a judge to issue a strong order to end the strike. Many people supported this order. But Harding felt it went too far. He had Daugherty change it. The order ended the strike. But tensions remained high between workers and management for years.

By 1922, the eight-hour day was common in American industry. But steel mills were an exception. Workers there worked twelve hours a day, seven days a week. Hoover thought this was wrong. He got Harding to call a meeting of steel makers. They wanted to end the long workdays. The meeting created a committee. It was led by U. S. Steel chairman Elbert Gary. In early 1923, the committee said not to end the practice. Harding sent a letter to Gary saying he was upset. It was printed in the news. Public outcry made the steel makers change their minds. They then made the eight-hour day standard.

Civil Rights and Immigration

Harding's first speech to Congress asked for an anti-lynching law. At first, he seemed to do little more for African Americans than past Republican presidents. He asked his cabinet to find jobs for black people in their departments. Some historians think Harding saw a chance for his party in the Solid South. On October 26, 1921, Harding gave a speech in Birmingham, Alabama. The audience was segregated. There were 20,000 white people and 10,000 black people. Harding said that social differences between white and black people could not be removed. But he urged equal political rights for black people. Many African Americans voted Republican then, especially in the Democratic South. Harding said he did not mind if that support ended. He wanted a strong two-party system in the South. He was okay with literacy tests for voting. But they had to be fair to both white and black voters. Harding told his audience, "Whether you like it or not... unless our democracy is a lie, you must stand for that equality." The white part of the audience was silent. The black part cheered. Three days after the Tulsa race massacre of 1921, Harding spoke at Lincoln University. It was an all-black school. He said, "Despite the demagogues, the idea of our oneness as Americans has risen superior to every appeal to mere class and group. And so, I wish it might be in this matter of our national problem of races." He spoke directly about Tulsa. He said, "God grant that... we never see another spectacle like it."

Harding supported Congressman Leonidas Dyer's federal anti-lynching bill. It passed the House in January 1922. When it reached the Senate in November 1922, Southern Democrats stopped it. Senator Lodge withdrew it to allow another bill Harding wanted to be debated. That bill was also blocked. Black people blamed Harding for the Dyer bill's defeat.

People were suspicious of immigrants. Especially those who might be socialists or communists. Congress passed the Per Centum Act of 1921. Harding signed it on May 19, 1921. It was a quick way to limit immigration. The law reduced immigrants to 3% of those from a country living in the U.S. This was based on the 1910 census. This would not limit immigrants from Ireland and Germany. But it would stop many Italians and Eastern European Jews. Harding and Secretary of Labor James Davis believed the law had to be fair. Harding allowed almost 1,000 immigrants who could have been sent away to stay. Coolidge later signed the Immigration Act of 1924. This law permanently limited immigration to the U.S.

Eugene Debs and Other Prisoners

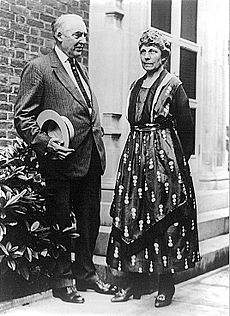

Harding's Socialist opponent in the 1920 election was Eugene V. Debs. Debs was in prison for speaking against the war. Wilson had refused to pardon him. Daugherty met with Debs and was very impressed. Some veterans and others were against releasing him. Florence Harding was also against it. The president felt he could not release Debs until the war was officially over. But once the peace treaties were signed, he reduced Debs' sentence on December 23, 1921. Harding asked Debs to visit him at the White House before going home.

Harding released 23 other war opponents at the same time as Debs. He continued to review cases and release political prisoners during his presidency. Harding said releasing prisoners was needed to bring the nation back to normal.

Judicial Appointments

Harding appointed four judges to the Supreme Court of the United States. When Chief Justice Edward Douglass White died in May 1921, Harding was unsure. He had promised seats to both former president Taft and former Utah senator George Sutherland. He chose Taft as Chief Justice. Sutherland was appointed to the court in 1922. Two other conservative judges, Pierce Butler and Edward Terry Sanford, followed in 1923.

Harding also appointed judges to other federal courts. He appointed six judges to the United States Courts of Appeals. He appointed 42 judges to the United States district courts. He also appointed two judges to the United States Court of Customs Appeals.

Challenges and Western Tour

Before the 1922 elections, Harding and Republicans had kept many promises. But some promises, like cutting taxes for the rich, were not popular. The economy was not fully back to normal. Unemployment was at 11 percent. Workers were angry about the strikes. Republicans lost many seats in the House. They also lost eight seats in the Senate. Harding did not live to see the new Congress.

After the election, Congress met for a short "lame-duck" session. Harding felt his early view of the presidency was not enough. He had believed the president should suggest policies, but Congress should adopt them. He tried to get his ship subsidy bill passed, but failed. Once Congress left in March 1923, Harding's popularity started to rise. The economy was getting better. The programs of his capable cabinet members were showing results. Most Republicans knew they had to support Harding for re-election in 1924.

In early 1923, Harding did two things. People later said these showed he knew he would die. He sold his newspaper, the Star. He also made a new will. Harding had health problems sometimes. But when he felt good, he ate, drank, and smoked too much. By 1919, he knew he had a heart condition. Stress from the presidency and his wife's illness made him weaker. He never fully recovered from the flu in January 1923. After that, Harding, who loved golf, had trouble finishing a game. In June 1923, Ohio Senator Willis met with Harding. He only discussed two of five things he planned to. When asked why, Willis said, "Warren seemed so tired."

In early June 1923, Harding started a trip. He called it the "Voyage of Understanding." The president planned to cross the country. He would go north to Alaska Territory. Then he would travel south along the West Coast. After that, he would go by Navy ship from San Diego. He would travel along the Mexican and Central American West Coast. Then through the Panama Canal to Puerto Rico. He planned to return to Washington in late August. Harding loved to travel. He had wanted to visit Alaska for a long time. The trip would let him speak across the country. It would also let him do some politics before the 1924 campaign. And it would give him some rest from Washington's summer heat.

Harding's political advisors gave him a very busy schedule. Even though the president had asked for it to be cut back. In Kansas City, Harding spoke about transportation. In Hutchinson, Kansas, the topic was agriculture. In Denver, he spoke about his support for Prohibition. He continued west, giving many speeches. Harding had become a supporter of the World Court. He wanted the U.S. to join. Besides speeches, he visited Yellowstone and Zion National Parks. He also dedicated a monument on the Oregon Trail.

On July 5, Harding boarded USS Henderson in Washington state. He was the first president to visit Alaska. He spent hours watching the scenery from the ship. After several stops, the group left the ship at Seward. They took the Alaska Railroad to McKinley Park and Fairbanks. In Fairbanks, he spoke to 1,500 people in 94-degree heat. The group was supposed to return by the Richardson Trail. But because Harding was tired, they went by train.

On July 26, 1923, Harding visited Vancouver, British Columbia. He was the first sitting American president to visit Canada. He was welcomed by local leaders. He spoke to over 50,000 people. Two years after his death, a memorial to Harding was put up in Stanley Park. Harding visited a golf course. But he only played six holes before getting tired. After resting, he played the 17th and 18th holes. This was so it would look like he finished the game. He could not hide his tiredness. One reporter thought he looked so tired that a few days' rest would not be enough.

In Seattle the next day, Harding kept his busy schedule. He gave a speech to 25,000 people at the stadium at the University of Washington. In his last speech, Harding predicted Alaska would become a state. The president rushed through his speech. He did not wait for applause.

Death and Funeral

Harding went to bed early on July 27, 1923. This was a few hours after his speech in Seattle. Later that night, he called for his doctor. He complained of pain in his upper stomach. The doctor thought it was a stomach upset. But another doctor suspected a heart problem. The press was told Harding had a "stomach attack." His planned weekend in Portland was canceled. He felt better the next day. The train rushed to San Francisco. They arrived on the morning of July 29. He insisted on walking from the train to the car. Then he was rushed to the Palace Hotel. There, he got worse. Doctors found his heart was causing problems. He also had pneumonia. He was kept in bed in his hotel room. Doctors treated him. He seemed to get better. Hoover released Harding's foreign policy speech. It supported joining the World Court. The president was happy it was well received. By the afternoon of August 2, Harding seemed to be improving. His doctors let him sit up in bed. Around 7:30 pm, Florence was reading to him. It was a flattering article about him. She paused, and he told her, "That's good. Go on, read some more." These were his last words. She started reading again. A few seconds later, Harding moved suddenly and collapsed. He was gasping. Florence Harding immediately called the doctors. But they could not revive him. Harding was pronounced dead a few minutes later, at age 57. Harding's death was first thought to be a brain hemorrhage. Doctors at the time did not fully understand cardiac arrest symptoms. Florence Harding did not allow an autopsy.

Harding's sudden death shocked the nation. He was liked and admired. The press and public had followed his illness closely. They had been relieved by his apparent recovery. Harding's body was put in a casket on his train. The train traveled across the nation. Newspapers followed it closely. Nine million people lined the tracks. The train carried his body from San Francisco to Washington, D.C. He lay in state at the United States Capitol rotunda. After funeral services there, Harding's body went to Marion, Ohio, for burial.

In Marion, Harding's body was placed on a horse-drawn hearse. President Coolidge and Chief Justice Taft followed it. Then came Harding's widow and his father. They followed the hearse through the city. They passed the Star building. Finally, they reached the Marion Cemetery. The casket was placed in the cemetery's receiving vault. Guests at the funeral included inventor Thomas Edison and businessmen Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone. Warren Harding and Florence Harding, who died the next year, rest in the Harding Tomb. It was dedicated in 1931 by U.S. President Herbert Hoover.

Historical View

After his death, Harding was deeply mourned. Not just in the U.S., but worldwide. Many European newspapers called him a man of peace. American journalists praised him highly. Some said he gave his life for his country. His friends were shocked by his death. Daugherty wrote, "I can hardly write about it or allow myself to think about it yet." Hughes said, "I cannot realize that our beloved Chief is no longer with us."

Positive stories about Harding's life quickly followed his death. One was Joe Mitchell Chapple's Life and Times of Warren G. Harding, Our After-War President (1924). By then, the scandals were becoming known. The Harding administration soon became known for corruption. Books written in the late 1920s shaped Harding's bad reputation. Masks in a Pageant, by William Allen White, made fun of Harding. So did Samuel Hopkins Adams' fictional book, Revelry. These books showed Harding's time in office as very weak. President Coolidge wanted to seem different from Harding. He refused to dedicate the Harding Tomb. Hoover, Coolidge's successor, also did not want to. But with Coolidge there, he led the dedication in 1931. By then, the Great Depression was happening. Hoover was almost as disliked as Harding.

Adams continued to create a negative view of Harding. He wrote several non-fiction books in the 1930s. His book The Incredible Era—The Life and Times of Warren G. Harding (1939) was the last. In it, he called Harding "an amiable, well-meaning third-rate Mr. Babbitt, with the equipment of a small-town semi-educated journalist... It could not work. It did not work." Historian John Dean thinks White and Adams's books were unfair. He says they made the bad parts worse. They blamed Harding for everything wrong. They also did not give him credit for anything good. Dean notes, "Today there is considerable evidence refuting their portrayals of Harding. Yet the myth has persisted."

Harding's papers were opened for research in 1964. This led to some new books about him. Russell's The Shadow of Blooming Grove (1968) was controversial. It said rumors about his family deeply affected Harding. This caused his conservative views and his desire to get along with everyone. Coffey criticizes Russell's methods. He calls the book "largely critical, though not entirely unsympathetic." Murray's The Harding Era (1969) had a more positive view. It put Harding in the context of his time. Trani and Wilson said Murray went too far. They said he tried too hard to link Harding to his cabinet's successes. They also said he claimed a new, stronger Harding appeared by 1923 without enough proof.

Later books tried to change the view of Harding. Robert Ferrell's The Strange Deaths of President Harding (1996) challenged almost every story about Harding. He concluded that almost everything known about him was wrong. In 2004, John Dean wrote the Harding book in "The American Presidents" series. Coffey thought this book was the most revisionist. He said Dean skipped over some bad parts of Harding's life. This included his silence during the 1914 Senate campaign. His opponent was attacked for his faith.

Harding has often been ranked as one of the worst presidents. In a 1948 poll, historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. asked scholars their opinions. Harding was ranked last among 29 presidents. He has been last in many other polls since. Ferrell says this is because scholars only read sensational stories about Harding. Murray argued that Harding deserves more credit. He said Harding was as good as other presidents like Franklin Pierce or Calvin Coolidge. He said Harding's administration had more achievements than many others. Coffey believes that scholars' lack of interest has hurt Harding's reputation. He says scholars still rank Harding near the bottom.

Trani blames Harding's own lack of depth and decision-making. This led to his bad legacy. Still, some authors and historians want a new look at Harding's presidency. In The Spoils of War (2016), Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith ranked Harding first. This was based on fewest wartime deaths and highest income growth during his time. Murray argued that Harding set the stage for his administration's poor standing.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Warren G. Harding para niños

In Spanish: Warren G. Harding para niños

- Cultural depictions of Warren G. Harding

- Harding Home

- Laddie Boy, Harding's dog

- List of memorials to Warren G. Harding

- List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1920s: March 10, 1923

- List of presidents of the United States

- List of presidents of the United States by previous experience

- List of presidents of the United States who died in office

- Presidents of the United States on U.S. postage stamps

- Warren G. Harding Presidential Center

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |