Tulsa race massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tulsa race massacre |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the nadir of American race relations | |

Homes and businesses burned in Greenwood

|

|

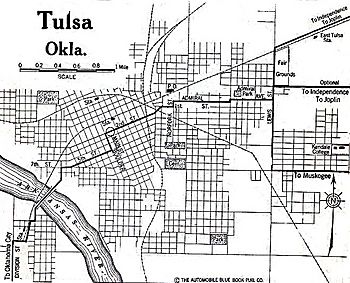

| Location | Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 36°09′34″N 95°59′11″W / 36.1594°N 95.9864°W |

| Date | May 31 – June 1, 1921 |

| Target | Black residents, their homes, businesses, churches, schools and municipal buildings over a 40 square block area |

| Deaths | Total dead and displaced unknown: 36 total; 26 black and 10 white dead (1921 records) 150–200 black and 50 white dead (1921 estimate by W. F. White) 39 confirmed, 26 black and 13 white dead 75–100 to 150–300 estimated (2001 commission) |

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

800+ 183 serious injuries Exact number unknown |

| Perpetrators | White American mob |

The Tulsa race massacre happened on May 31 and June 1, 1921. During these two days, groups of white people, some armed by city officials, attacked Black residents and destroyed homes and businesses in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. This event is also called the Tulsa race riot or Tulsa pogrom. It is known as one of the worst acts of racial violence and one of the deadliest terrorist attacks in U.S. history.

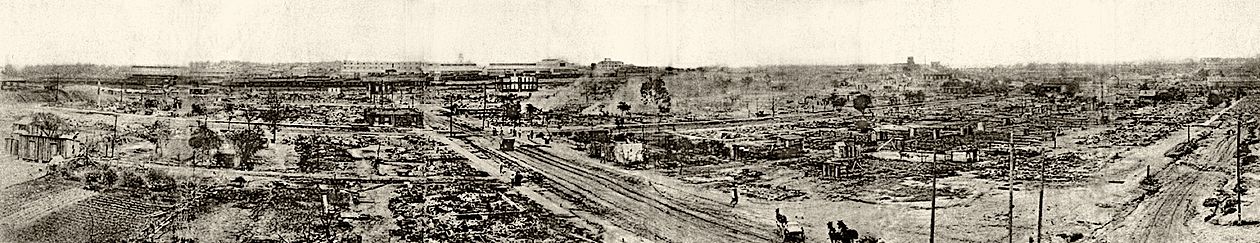

The attackers burned and destroyed more than 35 city blocks of the neighborhood. At the time, Greenwood was one of the richest African-American communities in the United States, often called "Black Wall Street." More than 800 people were hurt and needed hospital care. About 6,000 Black residents were held in large facilities, some for several days.

Official records from 1921 listed 36 people dead. A 2001 study found 39 confirmed deaths, including 26 Black people and 13 white people. This study also estimated that the total number of deaths could have been between 75 and 300.

The massacre started during Memorial Day weekend. A 19-year-old Black shoeshiner named Dick Rowland was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white elevator operator. Rowland was arrested. When a large group of white men gathered around the jail, about 75 Black men went to protect Rowland. The sheriff convinced the Black group to leave, saying he had things under control.

As the Black men left, a white man tried to take a pistol from a Black man. A shot was fired, and a gunfight began. At the end, 12 people were dead: 10 white and two Black. News of the violence spread, and mob attacks exploded. White rioters invaded Greenwood that night and the next morning. Around noon on June 1, the Oklahoma National Guard stepped in, ending the massacre.

About 10,000 Black people lost their homes. Property damage was huge, totaling over $2 million in today's money. Many survivors left Tulsa. Those who stayed, both Black and white, often kept quiet about what happened for decades. The massacre was mostly left out of local, state, and national history books.

In 1996, 75 years later, Oklahoma lawmakers created a group to study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. Their report in 2001 said that the city had worked with the white mob against Black citizens. It suggested that survivors and their families should receive reparations. The state then passed laws to create scholarships for descendants, help Greenwood's economy, and build a park to remember the victims. The park opened in 2010. Since 2002, Oklahoma schools have been required to teach students about the massacre. In 2020, it officially became part of the state's school curriculum.

Contents

- Understanding the Background

- The Spark: May 30-31, 1921

- The Massacre: June 1, 1921

- Aftermath and Impact

- Survivors' Stories

- Tulsa Race Massacre Commission

- After the Commission's Report

- President Biden's Visit

- Tulsa Historical Society and Museum

- Present-Day Black Wall Street

- In Popular Culture

- See also

Understanding the Background

In 1921, Oklahoma had a lot of tension between different racial and social groups. The state had many settlers from the Southern U.S. whose families had owned slaves. When Oklahoma became a state in 1907, its first laws created racial segregation, known as Jim Crow laws. These laws kept Black and white people separate.

For example, Black Americans were not allowed to serve on juries or hold local public offices. These laws stayed in place until the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 made them illegal. Tulsa also passed laws in 1916 that forced people to live in separate neighborhoods based on race. Even though the U.S. Supreme Court said these laws were unconstitutional, Tulsa and other cities kept them going for decades.

After World War I ended in 1918, many soldiers returned home. As they looked for jobs, tensions grew, especially in cities where jobs were hard to find. An economic downturn in Oklahoma also led to more unemployment. The American Civil War, which ended in 1865, was still in people's memories, and African Americans still lacked many basic civil rights.

The Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacist group, was growing across the country. By the end of 1921, about 3,200 of Tulsa's 72,000 residents were Klan members. At the same time, Black veterans felt they had earned full citizenship because of their military service and pushed for their rights. In 1919, many U.S. cities saw severe race riots, known as the "Red Summer." White mobs attacked Black communities, sometimes with help from local police.

Tulsa was a booming oil city with many wealthy and educated African-American residents. The Greenwood District was founded in 1906. It became so successful that it was known as "the Black Wall Street." Most Black people lived together in this area. They created their own businesses, including stores, newspapers, movie theaters, nightclubs, and churches. Black doctors, dentists, lawyers, and clergy served the community. Greenwood residents chose their own leaders and raised money to support their economic growth.

The Spark: May 30-31, 1921

An Encounter in an Elevator

On May 30, 1921, 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a Black shoeshiner, entered an elevator in the Drexel Building. He was going to use the "colored" restroom on the top floor. He met Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white elevator operator. They likely knew each other from Rowland's regular trips on the elevator.

A store clerk nearby heard what sounded like a woman's scream. He saw Rowland rushing from the building and found Page upset. Thinking she had been attacked, he called the police. Many believe Rowland tripped and grabbed Page's arm to catch himself, causing her to scream.

The 2001 Oklahoma Commission report noted that it was unusual for both Rowland and Page to be working on Memorial Day, when most businesses were closed. Rowland may have been working because his shine parlor was open for parade traffic. Page might have been working to take building employees to good spots to watch the parade.

Police Investigation and Arrest

Police questioned Page, but no written statement from her was found. She reportedly told police that Rowland had grabbed her arm but she would not press charges. The police decided it was not a serious assault and did not launch a big search for Rowland.

However, Rowland knew the situation was dangerous. He quickly went to his mother's house in the Greenwood neighborhood. The next morning, May 31, police found and arrested Rowland. He was taken to the city jail and later moved to the more secure jail on the top floor of the Tulsa County Courthouse.

Newspaper Spreads the News

The Tulsa Tribune, a white-owned newspaper, reported the story in its afternoon edition. Some witnesses said this edition included an editorial that warned of a threat to Rowland. All original copies of this newspaper page are missing, so the exact content of the editorial is unknown. However, the Chief of Detectives, James Patton, later said the newspaper story was the main cause of the riots. He believed if only the facts had been printed, the riot would not have happened.

Standoff at the Courthouse

News spread quickly after the Tribune came out. By 4 p.m., white residents began gathering near the Tulsa County Courthouse. By sunset, about 7:30 p.m., hundreds of white people were outside. The sheriff, Willard M. McCullough, tried to keep Rowland safe. He put deputies around Rowland and on the courthouse roof. He also blocked the building's elevator and stairs. The sheriff tried to tell the crowd to go home, but they would not leave.

Around 9:30 p.m., a group of about 50–60 armed Black men arrived at the jail to help the sheriff protect Rowland. The sheriff told them he did not need their help.

Tensions Rise and Shots Fired

After seeing the armed Black men, some of the white crowd went home to get their own guns. Others went to the National Guard armory to get weapons, but the Guard prevented them from breaking in.

At the courthouse, the crowd grew to nearly 2,000 people. Local leaders tried to calm the mob. Meanwhile, in Greenwood, Black residents were very worried about Rowland. Small groups of armed Black men drove toward the courthouse to see what was happening and show they were ready to protect Rowland. Many white men saw this as a "Negro uprising."

Around 10 p.m., a second, larger group of about 75 armed Black men went to the courthouse. They offered to help the sheriff, but he again refused.

There are different stories about how the shooting started. The 2001 Commission said that as the Black men were leaving, a white man tried to disarm a Black World War I veteran. A struggle happened, and a shot was fired. This led to a gunfight where 12 people died: 10 white and two Black. Another account says the shooting started "down the street from the Courthouse" when Black business owners defended a Black man being attacked by white men. As news of the violence spread, mob violence exploded across the city.

The Massacre: June 1, 1921

Fires and Attacks Begin

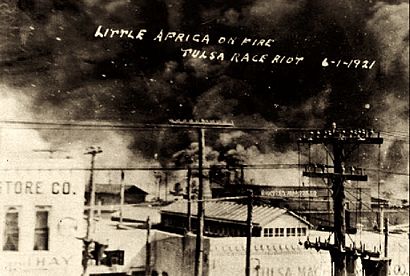

Throughout the early morning hours of June 1, armed groups of white and Black men fought. The fighting was mostly along the Frisco tracks, which divided the Black and white business areas. White rioters drove into Greenwood, shooting into businesses and homes. They often faced return fire. White rioters also started throwing burning rags into buildings along Archer Street, setting them on fire.

As the violence spread, many white families who had Black employees were stopped by rioters. The rioters demanded that the families hand over their Black employees to be taken to detention centers. Many white families did so, but those who refused were also attacked.

Around 1 a.m., the white mob began setting more fires, mainly in businesses on Archer Street, at the edge of Greenwood. As news spread, many Greenwood residents took up arms to defend their neighborhood. Others began to flee the city.

When Tulsa Fire Department crews arrived to put out fires, they were reportedly turned away at gunpoint. By 4 a.m., about two dozen Black-owned businesses were burning.

Daybreak and Full Assault

At sunrise, around 5 a.m., a train whistle sounded. Some rioters thought this was a signal for a full attack on Greenwood. Crowds of rioters, on foot and in cars, poured into the neighborhood. They shot randomly. Breaking into small groups, they looted houses and buildings. Many residents later said rioters forced them out of their homes and made them walk to detention centers. A rumor spread that the new Mount Zion Baptist Church was being used as a fortress and armory.

Attack from the Air

Many people who saw the massacre said that airplanes carrying white attackers flew over Greenwood. These planes reportedly fired rifles and dropped firebombs. These were private planes from a nearby airfield. Law enforcement later said the planes were for looking around and protecting against a "Negro uprising."

Eyewitnesses, including attorney Buck Colbert Franklin, described seeing "a dozen or more" planes circling the neighborhood on the morning of June 1. They reported that the planes dropped "burning turpentine balls" on buildings, causing them to catch fire from the top. Franklin also reported hearing "thousands and thousands of guns" being fired at the same time.

Some historians have questioned whether bombs were actually dropped from planes, saying there is no clear evidence of explosions. However, state representative Don Ross, who was born in Tulsa, disagreed and believed bombs were indeed dropped.

National Guard Arrives

Adjutant General Charles Barrett of the Oklahoma National Guard arrived around 9:15 a.m. with 109 troops. He declared martial law at 11:49 a.m. By noon, the troops had mostly stopped the violence.

Thousands of Black residents had fled the city. Another 4,000 people were rounded up and held in detention centers, including Convention Hall and the Tulsa County Fairgrounds. Under martial law, these detainees had to carry identification cards. As many as 6,000 Black Greenwood residents were held in these places. Martial law ended on June 4.

Aftermath and Impact

How Many People Died?

The number of deaths from the massacre varies widely in reports. On June 1, 1921, the Tulsa Tribune first reported 9 white and 68 Black deaths, then changed it to 176 total. The next day, it reported 9 white and 21 Black deaths. Other newspapers gave different numbers, from 33 to 175. The Oklahoma Department of Vital Statistics officially recorded 36 deaths (26 Black and 10 white).

Walter Francis White of the NAACP estimated 50 white and 150 to 200 Black deaths. The 2001 Oklahoma Commission estimated between 75 and 300 deaths. The American Red Cross did not give an official number, saying the number of dead was "a matter of conjecture" (a guess).

The Red Cross played a big role in helping the nearly 100,000 people affected in Greenwood. They provided security, food, shelter, job training, health care, and legal help. They set up the first hospital for Black patients in Oklahoma and gave mass vaccinations. Their work helped thousands of Black Tulsans stay in the city.

Property Losses and Rebuilding Efforts

The business area of Greenwood was completely destroyed. This included 191 businesses, a junior high school, several churches, and the only hospital in the district. The Red Cross reported that 1,256 houses were burned and another 215 were looted. Property losses were estimated at millions of dollars.

The Red Cross reported that 10,000 people were left homeless. Over the next year, citizens filed over $1.8 million in claims against the city for riot-related damages.

Governor James B. A. Robertson ordered an investigation into the events. A Grand Jury was formed, and after hearing witnesses for 12 days, it blamed the riot on the Black mobs. It also noted that law enforcement had failed to prevent the riot. More than 85 people were charged, but no one was ever convicted.

A group of over 1,000 businessmen and civic leaders met to raise money to rebuild Greenwood. Judge J. Martin, a former mayor, said Tulsa needed to make up for the "unspeakable crime" and pay for the damage. Many Black families spent the winter of 1921–1922 living in tents as they worked to rebuild.

However, a group of white developers tried to stop Black people from rebuilding in Greenwood. They wanted to use the land for new businesses and industries, forcing Black residents to live further away. This led to a legal battle. Attorney Buck Colbert Franklin appealed the case to the Oklahoma Supreme Court, which ruled the new building law unconstitutional. Most of the promised money for Black residents was never raised, making rebuilding very difficult.

Breaking the Silence

For decades, there was silence about the massacre. It was rarely mentioned in history books, classrooms, or even in private conversations. Many people grew up not knowing what had happened.

Several people tried to document the events. Mary E. Jones Parrish, a Black teacher and journalist, wrote a book called Events of the Tulsa Disaster in 1922. It was the first book about the riot and included her own experiences, other eyewitness accounts, and a list of property losses.

In the early 1970s, a small group of survivors held a memorial service. Around the same time, Mozella Franklin Jones and Ruth Sigler Avery worked to publicize accounts of the riot, but they faced pressure to keep quiet.

Survivors' Stories

The Tulsa Massacre deeply affected many lives. While estimates vary, hundreds died and over 800 were seriously injured. Many more had their lives changed forever.

Olivia Hooker

Olivia Hooker was born in 1915. When she was six, her family's home in Greenwood was broken into by white men, and many of their belongings were destroyed. Her father's store was also ruined. After the massacre, her family moved to Kansas. Olivia later became the first African American woman to join the United States Coast Guard in 1945. She earned advanced degrees in psychology and worked helping others. Olivia Hooker passed away in 2018 at the age of 103.

Eldoris McCondichie

Eldoris McCondichie was born in 1911. She was nine years old when the massacre happened. Her family had to leave their home quickly, without even time to get dressed. They found refuge at a farmer's home and then traveled to another town for a few days. When they returned to Tulsa, Eldoris described Greenwood as "war-torn." Her family slowly rebuilt their lives and stayed in Tulsa. She passed away in 2010 at 99 years old.

George Monroe

George Monroe was five years old during the attack. He said some images from that time never left his mind. He lived the rest of his life in Tulsa, becoming a musician, a nightclub owner, and the first Black man in Tulsa to sell Coca-Cola. George Monroe died in 2001.

Mary E. Jones Parrish

Mary Elizabeth Jones Parrish (1892–1972) was a teacher and journalist. She was at home when the massacre began. Her daughter pointed out men with guns outside. Mary Parrish wrote a firsthand account and collected stories from dozens of others, publishing them in her book, The Events of the Tulsa Disaster. She wanted her book to show people the danger of such events. A new edition of her book was published in 2021.

Lessie Benningfield ("Mother Randle")

Lessie Benningfield was born in 1914. She was very young during the massacre but remembers feeling intense fear while trying to escape with her family. She graduated from Booker T. Washington High School. As a survivor, she is part of a lawsuit seeking justice for victims. In 2020, for her 106th birthday, the community raised money to remodel her home. She remained in the public eye during the 2021 centennial anniversary.

Hal Singer

Hal Singer was born in 1919. He was 18 months old during the massacre. A white woman his mother worked for helped his family get on a train to Kansas City for safety. When they returned, their home was burned down, and they had to rebuild everything. Hal later became a famous saxophonist, playing with artists like Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday. He passed away in 2020, just before his 101st birthday.

Essie Lee Johnson Beck

Essie Johnson (1916-2006) was five years old when the massacre happened. Her parents made her and her siblings stay away from the windows. She remembers feeling scared and confused. Her family had to leave their home as it was burning. Her mother took Essie and her siblings to find shelter, and Essie recalled seeing airplanes dropping bombs. They hid in parks, churches, and school basements. When they returned, their home was gone, and they lived in a tent while it was rebuilt.

Vernice Simms

Vernice Simms was 17 during the massacre. She was preparing for prom when everyone was told to get inside. She and her family found safety at a white family's home. When they returned, their Greenwood home was burned down, and they had to live in a tent. Vernice volunteered at Booker T. Washington High School, which had become a hospital for the wounded. She finished high school in Oklahoma City and later attended Langston University. She never received money from insurance or the government to help.

Lena Eloise Taylor Butler

Eloise Taylor was 19 and lived in Greenwood during the massacre. She was the daughter of Horace Greeley Beecher Taylor, known as "Peg Leg" Taylor. Eloise witnessed some of the first gunfights. Her father helped her escape into the woods north of the city, where they hid. They walked for miles to a nearby town for help and decided never to talk about it again. Eloise finally shared her story with her great-granddaughters in 1997, a few years before she died in 2000 at age 98.

Tulsa Race Massacre Commission

In 1996, as the 75th anniversary of the riot approached, the Oklahoma state legislature created a commission to investigate the Tulsa Race Riot. Its name was later changed to the "Tulsa Race Massacre Commission." The commission interviewed people and gathered information to create a detailed historical report.

The commission released its final report on February 21, 2001. It suggested several actions to help the Black residents, including:

- Direct payments to survivors of the massacre.

- Direct payments to the families of survivors.

- A scholarship fund for students affected by the massacre.

- Creating an economic development zone in the historic Greenwood district.

- Building a memorial for the victims.

After the Commission's Report

Reconciliation Efforts

In March 2001, each of the 118 known survivors still alive received a gold-plated medal. The Tulsa Reparations Coalition was formed to seek payments for the damages suffered by Tulsa's Black community, as the commission had suggested. Tulsa Mayor Kathy Taylor apologized to survivors and gave them medals.

On June 1, 2001, Governor Frank Keating signed the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act. This law recognized that the event happened but did not include direct payments to victims or their families, even though the commission had recommended them. The act did provide:

- Over 300 college scholarships for descendants of Greenwood residents.

- A memorial for those who died. This park, named John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park, opened in 2010.

- Support for economic development in Greenwood.

Survivors' Lawsuit

In 2003, five survivors, with lawyers like Johnnie Cochran, sued the city of Tulsa and the state of Oklahoma. They based their lawsuit on the findings of the 2001 report. However, the courts dismissed the lawsuit, saying that the time limit for filing such cases had passed. The Supreme Court of the United States refused to hear their appeal.

Lawmakers tried to pass a bill in the U.S. Congress to extend the time limit for the case, but it did not pass.

John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park

A park was built in the Greenwood area in 2010 to remember the victims. It was named after John Hope Franklin, a famous African-American historian from Tulsa. The park has three statues representing Hostility, Humiliation, and Hope.

New Calls for Justice

In 2020, a detailed teaching plan about the massacre was given to Oklahoma schools.

On May 29, 2020, Human Rights Watch released a report asking for reparations for survivors and their families. They pointed out that the economic effects of the massacre are still seen today in north Tulsa, with higher poverty rates. Several documentaries were also planned for the 100th anniversary. In September 2020, a 105-year-old survivor sued the city for damages. In 2021, librarians successfully changed the official library terms for the event from "riot" to "massacre."

On May 19, 2021, three survivors, Viola Fletcher (107), Hughes Vann Ellis (100), and Lessie Benningfield Randle (106), spoke to a U.S. House committee about their experiences and their lawsuit.

President Biden's Visit

On June 1, 2021, the 100th anniversary of the massacre, President Joe Biden visited Tulsa. He was the first sitting president to do so. In his speech, he said, "Some injustices are so heinous, so horrific, so grievous, they cannot be buried, no matter how hard people try." Biden toured the Greenwood Cultural Center and met with survivors Viola Fletcher, Hughes Van Ellis, and Lessie Benningfield Randle.

Tulsa Historical Society and Museum

The Tulsa Historical Society and Museum has an online exhibit about the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. It is free and available all the time, offering photos, audio, documents, and other resources. They also have a traveling exhibit of four panels that can be displayed in the Tulsa area to educate the community.

Present-Day Black Wall Street

"Black Wall Street" still exists today as the Historical Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It took about 10 years to rebuild the district after the massacre. The historic Vernon AME Church is the only building still standing from before the 1921 massacre. Residents of Greenwood work to keep the memory of the Tulsa Race Massacre alive in the community. Today, many memorials honor the memory of what was once Black Wall Street. Investigations are still ongoing in the Greenwood District, hoping to find more unmarked graves and identify more victims of the Massacre.

In Popular Culture

Books and Stories

- The Nation Must Awake: My Witness to the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 (2021) by Mary E. Jones Parrish, is a book of eyewitness accounts from a survivor.

- Magic City (1998) and Fire in Beulah (2001) are novels set during the massacre.

- The Burning: Massacre, Destruction, and the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (2001) is a non-fiction book about the event.

- Tulsa Burning (2002) is a novel for middle-grade readers set during the riot.

- "The Case for Reparations" (2014) in The Atlantic is an article that brought more attention to the massacre.

- Dreamland Burning (2017) is a novel that connects the 1921 events to modern times.

- Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre (2021) is a children's book that won the Caldecott Medal.

Movies and TV Shows

- Going back to T-Town (1993) and The Tulsa Lynching of 1921: A Hidden Story (2000) are documentaries about the massacre.

- Before They Die (2008) tells the stories of the last survivors and their fight for justice.

- Watchmen (2019) on HBO starts with scenes of the riots and explores racial tensions. It was one of the first times the massacre was shown in entertainment.

- Lovecraft Country (2020) on HBO features characters traveling back in time to the night of the massacre.

Music and Art

- Graham Nash's song "Dirty Little Secret" (2002) is about the Tulsa race massacre.

- Scorched Earth (2006) is a painting by Mark Bradford about the event.

- The Gap Band, a group from Tulsa, was named after Greenwood, Archer, and Pine streets to remember the massacre.

See also

In Spanish: Disturbios raciales de Tulsa para niños

In Spanish: Disturbios raciales de Tulsa para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |