Charles Evans Hughes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Evans Hughes

|

|

|---|---|

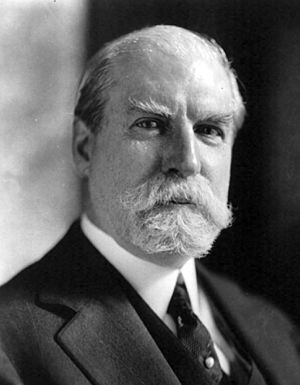

Hughes in 1931

|

|

| 11th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office February 24, 1930 – June 30, 1941 |

|

| Nominated by | Herbert Hoover |

| Preceded by | William Howard Taft |

| Succeeded by | Harlan F. Stone |

| Judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice | |

| In office September 8, 1928 – February 15, 1930 |

|

| Preceded by | John Bassett Moore |

| Succeeded by | Frank B. Kellogg |

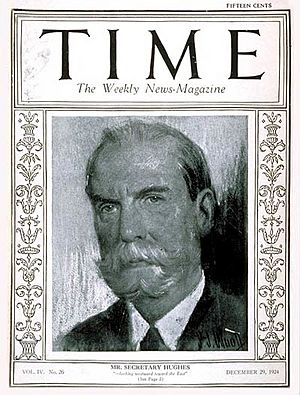

| 44th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 5, 1921 – March 4, 1925 |

|

| President | Warren G. Harding Calvin Coolidge |

| Preceded by | Bainbridge Colby |

| Succeeded by | Frank B. Kellogg |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office October 10, 1910 – June 10, 1916 |

|

| Nominated by | William Howard Taft |

| Preceded by | David Josiah Brewer |

| Succeeded by | John Hessin Clarke |

| 36th Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1907 – October 6, 1910 |

|

| Lieutenant | Lewis Stuyvesant Chanler Horace White |

| Preceded by | Frank W. Higgins |

| Succeeded by | Horace White |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 11, 1862 Glens Falls, New York, U.S. |

| Died | August 27, 1948 (aged 86) Osterville, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Antoinette Carter

(m. 1888; died 1945) |

| Children | 4, including Charles and Elizabeth |

| Education | Colgate University Brown University (AB) Columbia University (LLB) |

| Signature |  |

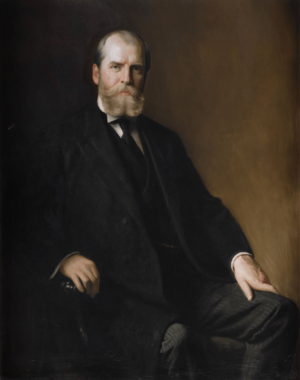

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (born April 11, 1862 – died August 27, 1948) was an important American leader. He served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. Before that, he was the 36th Governor of New York (1907–1910). He also served as an associate justice on the Supreme Court (1910–1916). Later, he became the 44th U.S. Secretary of State (1921–1925).

Hughes was a member of the Republican Party. He ran for President of the United States in 1916. He lost a very close election to Woodrow Wilson. If he had won, he would have been the first former Supreme Court justice to become president.

Born in Glens Falls, New York, Hughes was the son of a Welsh preacher. He went to Brown University and Columbia Law School. He then became a lawyer in New York City. In 1905, he led important state investigations. These looked into companies that provided public services and life insurance.

He was elected Governor of New York in 1906. As governor, he made many progressive changes. In 1910, President William Howard Taft appointed him to the Supreme Court. While on the Court, Hughes often agreed with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.. They both voted to support state and federal laws that regulated businesses.

Hughes left the Supreme Court in 1916 to run for president. After losing, he became Secretary of State in 1921. He worked for Presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. He helped create the Washington Naval Treaty. This treaty aimed to stop a naval arms race between the U.S., the United Kingdom, and Japan.

In 1930, President Herbert Hoover appointed him Chief Justice. The Hughes Court faced many challenges during the Great Depression. It had to decide on the legality of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs. Hughes retired in 1941.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Family Life

- Legal Career and Public Service

- Governor of New York

- Associate Justice of the Supreme Court

- Presidential Candidate

- Secretary of State

- Return to Private Life

- Judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice

- Chief Justice of the United States

- Retirement and Death

- Legacy

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education

Charles Evans Hughes was born in Glens Falls, New York, on April 11, 1862. His father, David Charles Hughes, was a Baptist preacher from Wales. His mother was Mary Catherine Connelly. Charles was their only child.

His family moved several times when he was young. They lived in Oswego, New York, Newark, New Jersey, and Brooklyn. For much of his early life, his parents taught him at home. In 1874, he started attending Public School 35 in New York City. He graduated the next year.

At 14, Hughes went to Madison University (now Colgate University). After two years, he transferred to Brown University. He graduated from Brown at age 19. He was third in his class. He was also part of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society.

After college, Hughes taught for a year in Delhi, New York. Then he went to Columbia Law School. He graduated first in his class in 1884. That same year, he got the highest score ever on the New York bar exam.

Family Life

In 1888, Hughes married Antoinette Carter. Her father was a senior partner at the law firm where Hughes worked. Their first child, Charles Evans Hughes Jr., was born a year later.

Charles and Antoinette had four children in total: one son and three daughters. Their youngest daughter, Elizabeth Hughes, was one of the first people to receive insulin. She later became president of the Supreme Court Historical Society.

Legal Career and Public Service

Hughes started working at a Wall Street law firm in 1883. He focused on contracts and bankruptcies. He became a partner in 1888. The firm's name changed to Carter, Hughes & Cravath.

From 1891 to 1893, Hughes taught at Cornell Law School. He then returned to his law firm. He also helped revise New York's legal rules.

Investigating Corrupt Companies

In 1905, New York Governor Frank W. Higgins asked Hughes to lead an investigation. This investigation looked into companies that provided public services, like gas and electricity. Hughes was chosen because of his strong performance in court.

Hughes focused on Consolidated Gas, a major gas company in New York City. He showed that the company had avoided taxes and kept false financial records. As a result, Hughes helped pass new laws. These laws created a commission to regulate public services. They also lowered gas prices for people.

Hughes's success made him very popular. He was then asked to investigate major life insurance companies in New York. This investigation, called the Armstrong Insurance Commission, uncovered many problems. It showed that companies paid journalists and lobbyists secretly. They also gave huge raises to executives while policyholders' dividends dropped.

Republican leaders tried to stop Hughes by offering him the nomination for Mayor of New York City. But Hughes refused. His work led to many top insurance officials being fired or resigning. He also helped pass laws that stopped insurance companies from owning corporate stock or doing banking activities.

Governor of New York

In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt encouraged Hughes to run for Governor of New York. Roosevelt saw Hughes as a "sane and sincere reformer." Hughes ran against newspaper owner William Randolph Hearst.

During his campaign, Hughes spoke out against corruption. He also supported an eight-hour workday for public projects. He wanted to stop child labor. Hughes was not a flashy speaker, but he worked hard. He won the election against Hearst.

Reforming State Government

As governor, Hughes focused on making government better and fighting corruption. He increased the number of government jobs based on merit, not political connections. He also gave more power to commissions that regulated public services.

Hughes signed laws that limited political donations from companies. He also required politicians to track their campaign money. He passed laws to protect young workers from dangerous jobs. He set a maximum 48-hour workweek for manufacturing workers under 16. To enforce these laws, he reorganized the New York State Department of Labor.

Leading the Baptists

Hughes was a lifelong Northern Baptist. In May 1907, he helped create the Northern Baptist Convention. He became its first president. His goal was to unite thousands of independent Baptist churches in the North. This was an important step in the history of American Baptists.

Second Term as Governor

Hughes's relationship with President Roosevelt became strained. Roosevelt chose not to run for president in 1908. He instead supported William Howard Taft. Taft asked Hughes to be his running mate, but Hughes said no.

Hughes considered leaving the governorship. But Taft and Roosevelt convinced him to run for a second term. He won re-election in 1908. His second term was less successful than his first. His main goal was a direct primary law, but it did not pass. However, he did get more regulation over telephone and telegraph companies. He also passed the first workers' compensation bill in U.S. history.

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court

By 1910, Hughes wanted to leave his role as governor. A spot opened on the Supreme Court when Justice David J. Brewer died. President Taft offered the position to Hughes, who quickly accepted. The Senate confirmed him unanimously on May 2, 1910.

Hughes became friends with other justices, including Chief Justice White and Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.. In his decisions, Hughes often agreed with Holmes. He supported state laws that set minimum wages. He also upheld laws for workers' compensation and maximum work hours for women and children.

He wrote opinions that supported the federal government's power to regulate trade between states. For example, in the 1914 Shreveport Rate Case, he upheld the government's right to stop unfair railroad rates. This decision showed that the federal government could regulate trade within a state if it affected trade between states.

Hughes also wrote opinions that protected civil liberties. In McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Co., he ruled that railroads must treat African-Americans equally. In Bailey v. Alabama, he struck down a law that made it a crime for workers not to finish their labor contracts. He said this law violated the Thirteenth Amendment and discriminated against African-American workers. He also joined the decision in Guinn v. United States (1915), which banned "grandfather clauses" used to prevent African-Americans from voting.

Presidential Candidate

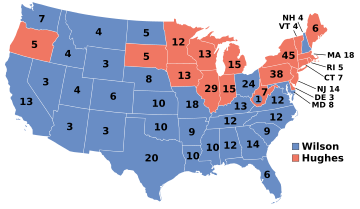

In 1912, the Republican Party was divided. This helped Democrat Woodrow Wilson win the presidency. To unite the party for the 1916 election, many Republicans asked Hughes to run. He was hesitant at first, but polls showed he was popular.

By June 1916, Hughes had won several primary elections. He secured the Republican nomination on the third ballot. He resigned from the Supreme Court to accept. He was the only sitting Supreme Court Justice ever to be a major party's presidential nominee.

Hughes was seen as the favorite against President Wilson. He was known for his intelligence and honesty. Both former President Taft and Theodore Roosevelt supported him. However, the Republican Party was still somewhat divided from 1912.

Hughes's campaign had some difficulties. He struggled to unite all parts of the Republican Party. Many former Progressive Party leaders supported Wilson. On election day, Hughes was still expected to win. He did well in the Northeast. But Wilson won several states in the Midwest, partly due to anti-war feelings. Wilson won the election by winning California by a very small margin.

After the Election

After losing, Hughes returned to his law firm. In 1917, he supported Wilson's decision to enter World War I. He chaired New York City's draft appeals board. He also investigated the aircraft industry for the government.

After the war, he returned to private law practice. He represented many clients, including five Socialists who had been removed from the New York legislature. He tried to help President Wilson and Senate Republicans agree on the League of Nations, but the Senate rejected it.

In 1920, many Republicans wanted Hughes to run for president again. But his daughter Helen died that year, and he refused to be considered. The Republicans nominated Warren G. Harding, who won the election.

Secretary of State

In 1921, President Harding asked Hughes to be his Secretary of State. Hughes accepted. When Chief Justice White died, Hughes was considered for that role. But he told Harding he wanted to stay at the State Department. Harding then appointed former President Taft as Chief Justice.

Harding gave Hughes a lot of freedom in foreign policy. Hughes believed the U.S. should be a world leader. He thought the U.S. should use diplomacy and agreements instead of military force.

Hughes initially favored the U.S. joining the League of Nations. However, President Harding and many senators strongly opposed it. So, Hughes convinced Harding to sign a separate peace treaty with Germany in 1921. He also wanted the U.S. to join the Permanent Court of International Justice, but the Senate did not agree.

Hughes's biggest achievement as Secretary of State was preventing a naval arms race. This was a competition to build the most powerful navy. The main naval powers were Britain, Japan, and the United States.

In 1921, Hughes invited these countries, along with Italy and France, to a naval conference in Washington. He wanted to limit the size of their navies. Hughes proposed a plan to stop all new warship construction. He also suggested limits on the total size of each country's navy. His plan was based on the 1920 ship tonnage ratio: 5:5:3 for the U.S., Britain, and Japan.

The Washington Naval Conference began in November 1921. Hughes surprised everyone by revealing his bold plan on the first day. He proposed scrapping many U.S. warships. The British supported his idea. The Japanese asked for some changes, but eventually agreed to the ratios.

Hughes also helped create the Four-Power Treaty. This treaty called for peaceful solutions to land claims in the Pacific Ocean. He also helped create the Nine-Power Treaty, which protected China's territory. The success of the conference was praised worldwide. Franklin D. Roosevelt later called it "the first important voluntary agreement for limitation and reduction of armament."

Other Foreign Policy Issues

After World War I, Germany's economy struggled. It had to pay war reparations to other countries. These countries, in turn, owed war debts to the United States. Hughes helped create an international committee to study lowering Germany's reparations. This led to the Dawes Plan in 1924. This plan set up annual payments from Germany.

Hughes wanted closer ties with the United Kingdom. He also sought better relations with countries in Latin America. He planned to remove U.S. troops from the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua. However, he felt that instability in Haiti required U.S. soldiers to stay. He also resolved a border dispute between Panama and Costa Rica.

Return to Private Life

Hughes stayed on as Secretary of State after President Harding died in 1923. He left office in early 1925. He returned to his law firm and became one of the highest-paid lawyers in the country.

He also served as a special judge in a case about Chicago's sewage system. He was elected president of the American Bar Association. He also helped start the National Conference on Christians and Jews.

Some leaders asked him to run for governor of New York in 1926. Others suggested he run for president in 1928. But Hughes declined. He supported Herbert Hoover for president in 1928. Hoover won and asked Hughes to be Secretary of State again, but Hughes said no. He had committed to serving as a judge on the Permanent Court of International Justice.

Judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice

Hughes served as a judge on the Permanent Court of International Justice from 1928 to 1930. This court helped settle disputes between countries.

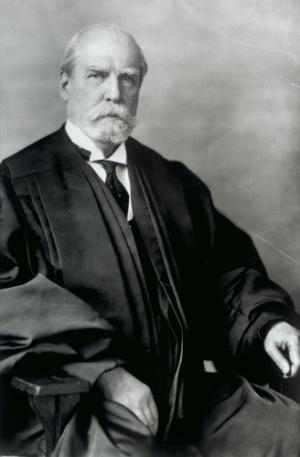

Chief Justice of the United States

On February 3, 1930, President Hoover nominated Hughes to become Chief Justice. The previous Chief Justice, William Howard Taft, was very ill. Some senators worried that Hughes would favor big businesses. This was because he had worked as a corporate lawyer.

However, the Senate confirmed Hughes on February 13, 1930, by a vote of 52–26. He took office on February 24, 1930. Hughes quickly became a strong leader on the Court. His intelligence and legal knowledge earned him respect from other justices.

The early Hughes Court was divided. There were conservative justices, sometimes called the "Four Horsemen." And there were liberal justices, known as the "Three Musketeers." Hughes and Justice Owen Roberts were often the swing votes between these two groups.

In 1931, Hughes joined the liberal justices in a major case, Near v. Minnesota. He wrote the majority opinion. This ruling said that the First Amendment prevented states from violating freedom of the press. He also wrote the opinion in Stromberg v. California. This was the first time the Supreme Court struck down a state law based on the incorporation of the Bill of Rights.

The New Deal and the Court

During President Hoover's time, the country fell into the Great Depression. Franklin D. Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election. He launched his New Deal programs to fight the Depression. The Supreme Court's response to these laws became a major issue.

In the "Gold Clause Cases" (1935), the Hughes Court upheld Roosevelt's decision to cancel "gold clauses" in contracts. Roosevelt was happy, seeing it as the Court putting "human values ahead of the 'pound of flesh'." In Home Building & Loan Ass'n v. Blaisdell (1934), Hughes and the liberal justices upheld a Minnesota law. This law temporarily stopped mortgage payments. Hughes wrote that an emergency could allow for the use of power.

However, starting in 1935, Justice Roberts began siding with the conservative justices. This created a majority that struck down many New Deal laws. In A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935), the Court unanimously struck down a key New Deal law. Hughes wrote that the law was unconstitutional.

In 1936, the Court struck down the Agricultural Adjustment Act. This was a major New Deal farm program. In another case, Carter v. Carter Coal Co. (1936), the Court struck down a law regulating the coal industry. Hughes agreed that Congress could not regulate activities within states that only indirectly affected trade between states. In Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo (1936), the Court struck down New York's minimum wage law. This decision angered many, including President Roosevelt.

The Court-Packing Plan

After winning re-election in 1936, President Roosevelt worried the Court would strike down more New Deal laws. In early 1937, he proposed the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937. This plan would have allowed him to add more justices to the Supreme Court. Roosevelt argued that the justices were too old and couldn't handle their workload.

Many people saw this as Roosevelt trying to gain more power. Hughes worked behind the scenes to defeat the plan. He quickly moved important New Deal cases through the Court to uphold them. He also sent a letter to Senator Burton K. Wheeler. In it, Hughes stated that the Supreme Court was fully capable of handling its cases. This letter helped to discredit Roosevelt's argument.

While the debate continued, the Supreme Court upheld Washington state's minimum wage law in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937). Hughes wrote the majority opinion. He said the "Constitution does not speak of freedom of contract." This decision overturned a previous ruling. Many believed Justice Roberts changed his vote due to pressure from the court-packing plan. This is sometimes called "the switch in time that saved nine." However, Hughes and Roberts later said Roberts had decided to change his stance months earlier.

Weeks later, Hughes wrote for the majority again in NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. (1937). The Court upheld the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (Wagner Act). This case marked a turning point. The Court began to uphold New Deal laws. Later in 1937, the Court upheld the Social Security Act.

The court-packing plan eventually failed in the Senate. But throughout 1937, Hughes had overseen a major shift in how the Court viewed economic laws. This period, where the Court often struck down economic regulations, ended.

Later Years on the Court

After 1937, the Hughes Court continued to uphold economic regulations. The liberal justices gained more power as new justices were appointed. In United States v. Carolene Products Co. (1938), Justice Stone wrote that the Court would generally defer to economic regulations. This meant the Court would only strike down a law if legislators had no "rational basis" for passing it. Hughes joined the majority in United States v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941), which upheld the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

The Hughes Court also handled several civil rights cases. In Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938), Hughes wrote the majority opinion. It required Missouri to either integrate its law school or create a separate one for African-Americans. He also helped arrange unanimous support for Chambers v. Florida (1940). This case overturned a conviction where the defendant was forced to confess.

In 1940, Hughes joined the majority in Minersville School District v. Gobitis. This ruling said that public schools could require students to salute the American flag. This was allowed even if students had religious objections.

Hughes began thinking about retiring in 1940 due to his wife's health. In June 1941, he told President Roosevelt he would retire. Hughes suggested that Roosevelt make Justice Stone the new Chief Justice, which Roosevelt did. Hughes retired in 1941.

Retirement and Death

After retiring, Hughes generally stayed out of public life. He did review the United Nations Charter for Secretary of State Cordell Hull. He also suggested that President Harry S. Truman appoint Fred M. Vinson as Chief Justice after Stone's death.

Hughes lived in New York City with his wife, Antoinette, until she died in 1945. Charles Evans Hughes died on August 27, 1948, at age 86. He passed away in Osterville, Massachusetts. At the time of his death, he was the last living justice who had served on the White Court.

He is buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York City.

Legacy

Historian Dexter Perkins described Hughes as a good mix of liberal and conservative. He believed Hughes was wise enough to fix problems in society to preserve it. He also understood that change could bring risks. Perkins called him a "noble and constructive figure in American life."

Experts generally agree that Hughes was an outstanding Secretary of State. He had a clear vision for America's role in the world. He believed the United States should lead by promoting diplomacy and peaceful solutions. He was able to guide U.S. foreign policy and help the country become a major world power.

Hughes has been honored in many ways. Several schools, rooms, and events are named after him. The Hughes Range in Antarctica is also named for him. On April 11, 1962, the 100th anniversary of his birth, the U.S. Post Office issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. His former home in Washington, D.C., is now the Burmese ambassador's residence. It was named a National Historic Landmark in 1972.

Judge Learned Hand once said that Hughes was the greatest lawyer he had ever known. He added, "except that his son (Charles Evans Hughes Jr.) was even greater."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Charles Evans Hughes para niños

In Spanish: Charles Evans Hughes para niños

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 6)

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the White Court