Progressivism in the United States facts for kids

Progressivism in the United States is a way of thinking and a movement that aimed to make society better. It was most popular in the early 1900s. This movement started because of big changes happening in America. These changes included the growth of huge companies, pollution, and corruption in politics.

Progressivism focused on making things more fair and efficient. It wanted to solve problems that came with a rapidly changing country.

Contents

- What Was the Progressive Era?

- Making Elections Fair

- Improving City Government

- Efficiency in Government

- Fighting Corruption

- Education for Everyone

- Controlling Big Businesses

- Helping People in Need

- Protecting Nature

- National Politics and Culture

- Progressivism Today

- Progressive Political Parties

- Images for kids

What Was the Progressive Era?

The Progressive Era was a time of big changes in American history. It generally lasted from the 1890s until around World War I. During this time, many people wanted to fix problems caused by the "Gilded Age." The Gilded Age was a time when some people became very rich, but many others faced tough times.

Progressives believed in making society more efficient. They also wanted to get rid of waste and corruption. They supported laws for worker pay and better rules for child labor. They also pushed for a shorter workweek and a fair income tax. A major goal was also to give women the right to vote.

Making Elections Fair

Progressives believed that elections needed to be cleaner and more honest. They worried that illegal voting was harming the political system. They thought that powerful city bosses were rigging elections.

To fix this, they suggested several changes. One idea was to close down saloons, which were often seen as places where political deals and illegal voting happened. They also wanted new rules for voter registration. This would stop people from voting multiple times.

Many progressives also strongly supported giving women the right to vote. They believed that women voters would help make elections more honest. This was a big step towards making government more fair for everyone.

Improving City Government

Progressives often focused on making city and state governments better. Cities were growing very fast, and progressives wanted to find ways to provide services without waste. They aimed for a more organized system.

They wanted to put power into the hands of trained professionals. These experts could manage city services like legal processes and public administration. This made city government more solid and efficient. It replaced older, less organized systems.

People like Jane Addams helped by setting up "settlement houses." These places helped people in poor city areas. They offered education and cultural programs to improve life for city residents.

Efficiency in Government

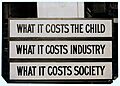

Many progressives wanted to make American governments work better for people. They believed that government operations should be more efficient and logical. For example, instead of just arguing against long workdays for women, they used scientific facts. They showed how long hours hurt both workers and society.

The idea was to use experts to make decisions. This sometimes meant taking power away from elected officials. Progressives who valued efficiency believed that trained experts could make better choices. They thought this would make government less corrupt. However, it also sometimes made government feel more distant from the people.

One big change was the rise of the "city manager" system. Here, professional engineers managed the daily tasks of city governments. They followed rules set by elected city councils. Many cities also created "reference bureaus." These groups studied government departments to find waste and inefficiency.

Fighting Corruption

Corruption was a big problem that caused waste and inefficiency in government. Leaders like Robert M. La Follette, Sr. in Wisconsin worked to clean up state and local governments. They passed laws to weaken the power of political bosses.

In Wisconsin, La Follette introduced an "open primary" system. This took away the power of party bosses to choose who would run for office. Other states also adopted similar reforms. These changes aimed to give ordinary citizens more control over their government.

Education for Everyone

Early progressive thinkers believed that a good education system was vital for a successful democracy. They worked hard to improve and expand public and private education for all ages. They felt that all children should go to school, even if their parents disagreed.

Progressives used research to improve education. They measured different parts of learning, which later led to standardized testing. Many of their ideas still influence education today. They wanted to make schools better and more responsive to the needs of students.

They also focused on making teaching a professional career. Teachers had to go to college. This made teaching a respected job for women. It also gave experienced teachers chances to guide younger ones.

Controlling Big Businesses

Many progressives hoped to control large companies. They wanted to free people from the problems caused by huge industrial businesses. However, progressives had different ideas on how to do this.

Breaking Up Monopolies

Some progressives, like Samuel Gompers, believed that huge monopolies were bad for the economy. They thought these monopolies stopped fair competition, which was needed for progress. Presidents like Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft supported "trust-busting." This meant breaking up these giant companies. For example, President Taft broke up 90 trusts in just four years.

Regulating Companies

Other progressives, like Benjamin Parke De Witt, thought that large companies were natural and even good for a modern economy. They believed these companies offered benefits that smaller ones could not. However, they also knew these big companies could abuse their power. So, they argued that the government should let these companies exist but control them for the public good. President Roosevelt also supported this idea.

Helping People in Need

Progressives wanted to make sure that social work and charity were done by trained professionals. They set up programs to teach people how to help others effectively.

Jane Addams was a famous progressive who ran settlement houses. These centers were in poor city neighborhoods. They aimed to improve the lives of city dwellers by offering adult education and cultural activities.

Stopping Child Labor

Progressives worked to create laws against child labor. These laws aimed to stop children from being overworked in factories. The goal was to give working-class children a chance to go to school and grow up properly. This would help them reach their full potential. Even though some factory owners resisted, child labor laws were eventually passed.

Supporting Workers' Rights

Labor unions grew steadily during this period. Leaders like Samuel Gompers and Theodore Roosevelt supported goals like the eight-hour workday. They also pushed for better safety in factories. Other important goals included laws for workers' compensation and minimum wage laws for women.

Protecting Nature

During President Theodore Roosevelt's time (1901–1909), many big projects to protect nature were started. These were the largest government-funded conservation efforts in U.S. history.

National Parks and Wildlife Refuges

On March 14, 1903, President Roosevelt created the first National Bird Preserve. This was the start of the Wildlife Refuge system in Florida. By 1909, Roosevelt's government had created a huge amount of protected land. This included 42 million acres of national forests, 53 national wildlife refuges, and 18 special areas like the Grand Canyon.

Water and Land Protection

Roosevelt also approved the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902. This law provided money for irrigation in many Western states. Another important law was the Antiquities Act of 1906. This allowed the president to declare large areas of land as "national monuments" to protect them. An Inland Waterways Commission was also set up to study U.S. river systems. This included looking at water power, flood control, and land reclamation.

National Politics and Culture

In the early 1900s, politicians from both the Democratic and Republican parties supported progressive ideas. These ideas included breaking up monopolies and supporting labor unions. They also wanted public health programs, less corruption, and environmental protection.

Progressivism was also shaped by journalists called "muckrakers." These writers exposed problems like economic unfairness and political corruption. Their articles appeared in popular magazines. For example, Ida Tarbell wrote about the unfair practices of the Standard Oil Company. Lincoln Steffens wrote about corruption in city governments.

Novelists also criticized corporate problems. Upton Sinclair's book The Jungle described the terrible conditions in Chicago meatpacking plants. This book helped lead to new laws about food safety.

Progressivism Today

Today, the term "progressive" is still used, but its meaning has changed a bit. Modern progressives often focus on different issues than those from the early 1900s.

Reducing Income Inequality

Modern progressives are concerned about the growing gap between rich and poor in the United States. They believe that lower union rates and other factors have caused this problem. They propose laws to reform Wall Street, change tax rules, and close loopholes.

For example, after the 2008 financial crisis, progressives pushed for stronger rules for banks. They want to make sure that big financial companies cannot take advantage of consumers.

Fair Wages

Progressives believe that wages have not kept up with the cost of living. They argue that raising the minimum wage is important to fight inequality. Some popular progressive politicians support a federal minimum wage of $15 an hour. This movement has already seen success in some states.

Protecting the Environment

Modern progressives strongly support protecting the environment. They want to reduce pollution. They also highlight that poor communities are often hurt the most by pollution and environmental damage. Leaders like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez advocate for big plans like the Green New Deal. This plan aims to address climate change and create jobs.

Progressive Political Parties

Besides the main progressive movement, there were also a few political parties that called themselves "Progressive."

Progressive Party (1912)

The first Progressive Party was formed for the 1912 presidential election. It was created to support Theodore Roosevelt for president. He ran after he lost the Republican nomination. This party was short-lived and ended by 1920.

Progressive Party (1924)

In 1924, Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr. ran for president on the Progressive Party ticket. He gained support from labor unions and other groups. He only won his home state of Wisconsin, and the party mostly disappeared after that.

Progressive Party (1948)

A third Progressive Party was started in 1948 by former Vice President Henry A. Wallace. He ran for president because he felt the other parties were too focused on war. This party attracted voters who were against the Cold War. However, it faded away after winning only a small percentage of the vote.

Images for kids

-

Upton Sinclair's The Jungle showed the harsh realities of meatpacking plants.

-

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez from New York, a supporter of climate action.