Ida Tarbell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ida Tarbell

|

|

|---|---|

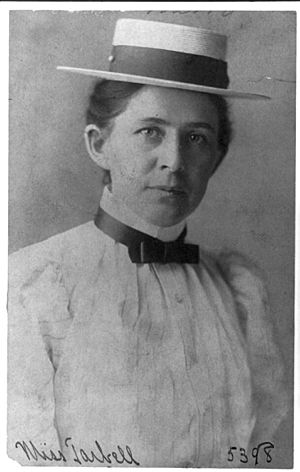

Portrait taken in 1904

|

|

| Born | Ida Minerva Tarbell November 5, 1857 Hatch Hollow, Amity Township, Erie County, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | January 6, 1944 (aged 86) Bridgeport, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Notable works | The History of the Standard Oil Company |

Ida Minerva Tarbell (born November 5, 1857 – died January 6, 1944) was an American writer, journalist, and lecturer. She was a pioneer in investigative journalism. This means she dug deep to find facts and expose problems.

Ida Tarbell was one of the most famous "muckrakers" during the Progressive Era. This was a time in the late 1800s and early 1900s when many people worked to fix problems in American society.

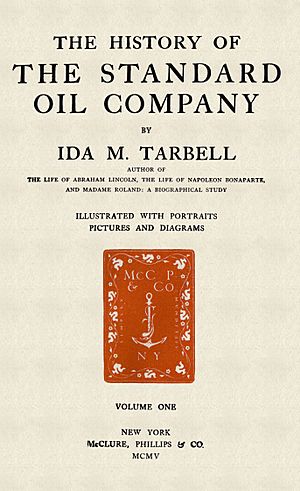

Tarbell is best known for her 1904 book, The History of the Standard Oil Company. This book showed how the powerful Standard Oil company used unfair methods to grow. Her work helped lead to laws that broke up big monopolies and created groups like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

She also wrote many biographies, which are life stories of real people. She wrote about famous figures like Napoleon and Abraham Lincoln. Tarbell believed that finding the truth about powerful people could help make important social changes. She was also known for making complicated topics easy to understand.

Tarbell was a busy writer and editor for magazines like McClure's Magazine and The American Magazine. She also traveled a lot, giving talks across the United States. She spoke about many topics, including peace, politics, big businesses, and women's issues.

Even though she never married, Ida Tarbell is often seen as a strong woman who showed what women could achieve. However, she was critical of the women's suffrage movement (the fight for women's right to vote) for much of her life.

Contents

Her Early Life and Education

Ida Minerva Tarbell was born on November 5, 1857, in Erie County, Pennsylvania. Her mother, Esther Ann, was a teacher. Her father, Franklin Summer Tarbell, was a teacher and later an oilman. She was born in her grandfather's log cabin.

Ida had three younger siblings. Her brother Franklin Jr. died young from scarlet fever. Her sister Sarah was often sick, and her brother Walter became an oilman like their father.

Ida Tarbell's early life in the oil fields greatly influenced her later writing. When she was born, her family lost their savings because banks failed. Her father had to walk across several states to get home, teaching in schools to earn money.

Their luck changed when the Pennsylvania oil rush began in 1859. They lived in an area where new oil fields were developing. Ida's father built wooden tanks for oil storage. She later wrote that the oil industry was very messy and destructive in its early days.

In 1860, her family moved to Rouseville, Pennsylvania. Ida saw terrible accidents there, including an oil well explosion that killed many men. Her mother even cared for one of the burn victims. These events gave Ida nightmares for years.

After the oil boom in Rouseville ended, her family moved to Titusville, Pennsylvania. Her father became an oil producer and refiner. However, his business, along with many others, was hurt by the South Improvement Company. This secret group worked with railroads to charge higher shipping rates for small oil businesses. Meanwhile, big companies like Standard Oil Company got discounts.

Ida's father fought against this unfair system. He even participated in protests and helped tip over Standard Oil railroad tankers. The government eventually stopped the South Improvement Company. These experiences deeply affected Ida and shaped her views on big business.

The Tarbell family was very involved in their community. They hosted people who supported prohibition (banning alcohol) and women's rights. Ida read newspapers like Harper's Weekly and followed the events of the American Civil War.

Ida Tarbell was a bright student, but sometimes she didn't pay attention in class. A teacher helped her focus. Ida became very interested in science, especially comparing what she learned in school to the nature around her.

She graduated at the top of her high school class in Titusville. In 1876, she went to Allegheny College to study biology. She was the only woman in her class of 41 students. Ida loved studying nature and believed that "the quest for the truth had been born in me."

At Allegheny, Ida was a leader. She helped start a sorority and led a project to place a stone on campus dedicated to learning. She also wrote for the college's women's literary society.

Tarbell graduated in 1880 and earned a master's degree in 1883. She later supported the college by serving on its board of trustees for over 30 years.

Starting Her Career

After college, Ida Tarbell wanted to help society but wasn't sure how. She became a teacher at Poland Seminary in Poland, Ohio, in 1880. She taught many subjects, including science, math, and languages. After two years, she realized teaching was too much work for too little pay, so she returned home.

Back in Pennsylvania, she met Theodore L. Flood, who edited The Chautauquan. This magazine provided learning materials for people studying at home. Ida quickly accepted his offer to write for the publication. She started by writing short pieces and then moved to longer articles.

Her first article, "The Arts and Industries of Cincinnati", was published in 1886. This article showed her writing style: she always included a strong moral message and aimed to bring about change.

Ida also wrote about women's roles. In 1887, she published "Women as Inventors." She found that nearly 2,000 women had patents, proving that women invented many useful things, not just "clothes and kitchen" items. She also wrote about women in journalism, encouraging them but warning them to be strong and not easily upset.

Tarbell eventually left The Chautauquan because she didn't want to be just a "hired gal." She wanted to work for herself, like her father believed. She began researching historical women like Madame Roland for inspiration and writing topics.

Life in Paris

In 1891, at age 34, Tarbell moved to Paris, France, to live and work. She shared an apartment with friends near famous landmarks like the Panthéon and Notre-Dame de Paris. Paris was an exciting city, and the Eiffel Tower had just been built.

Tarbell enjoyed the art of Impressionist painters like Claude Monet. She also had an active social life, hosting language practice sessions with her flatmates.

To support herself, Tarbell wrote for several American newspapers. She also published a short story in Scribner's Magazine. All this work helped her research her first biography, a book about Madame Roland, a leader during the French Revolution. Tarbell wanted to bring women's stories out of history's shadows.

In Paris, Tarbell continued her education. She learned investigative and research methods from French historians. She attended lectures at the Sorbonne, learning how to present facts clearly and powerfully.

Her research on Madame Roland changed Tarbell's own views. She started admiring Roland but realized that Roland, by following her husband, helped create a violent atmosphere during the revolution. This made Tarbell question her own belief in revolution as a good way to bring change.

While in Paris, Tarbell received shocking news. Her hometown of Titusville was destroyed by a flood and fire in 1892. Over 150 people died. Luckily, her family and their home were safe.

McClure's Magazine

Ida Tarbell had already written for Samuel McClure's newspaper group. McClure was impressed by her writing and wanted her to work for his new publication, McClure's Magazine. He visited her in Paris in 1892 and offered her an editor position.

Tarbell initially said no because she wanted to finish her Roland biography. But McClure was determined. She eventually agreed to write freelance articles for the magazine. She wrote about women thinkers and scientists in Paris. She even interviewed the famous scientist Louis Pasteur.

Tarbell returned to the United States in 1894 and joined McClure's staff.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Samuel McClure asked Tarbell to write a series of articles about the French leader Napoleon Bonaparte. McClure wanted to compete with another magazine that was also writing about Napoleon. Tarbell worked quickly, publishing her first article just six weeks after starting. She called it "biography on a gallop."

This series helped Tarbell develop her writing style. She believed that extraordinary people could shape society. She also learned to use "primary sources" (original documents) and present evidence clearly.

The Napoleon series was very popular. It doubled McClure's circulation to over 100,000 readers. The articles were later published as a book, which became a bestseller and earned Tarbell money for the rest of her life.

Abraham Lincoln

McClure's also wanted a story about US president Abraham Lincoln to compete with another magazine. At first, Tarbell wasn't sure, but she had been fascinated by Lincoln since she was a girl. She remembered her parents' sadness when he was assassinated.

Tarbell decided to focus on Lincoln's early life. She traveled across the country, meeting and interviewing people who had known him. She even spoke with his son, Robert Todd Lincoln, who shared a never-before-seen photo of his father.

Tarbell's research in Kentucky and Illinois uncovered the true story of Lincoln's childhood. She wrote to and interviewed hundreds of people. She found more than 300 previously unpublished letters and speeches by Lincoln.

By 1895, Tarbell's popular series helped McClure's circulation grow to over 250,000. This happened even though rival editors joked, "They got a girl to write the Life of Lincoln." McClure used the money from Tarbell's articles to buy his own printing plant.

Because of this success, Tarbell became a nationally recognized writer and the leading expert on Lincoln. She published five books about him and gave many lectures.

The demanding writing schedule and constant travel affected Tarbell's health. She often had to rest and recover at a sanitarium (a type of health resort).

Becoming an Editor

Tarbell continued writing for McClure's in the late 1890s. She observed the United States expanding its power during the Spanish–American War. She was even at the U.S. Army Headquarters when the battleship USS Maine exploded.

In 1899, Tarbell moved to New York City and became a desk editor for McClure's. She was paid well and even owned shares in the company. She became a steady presence at the magazine as it hired more investigative writers.

Investigating Standard Oil

Around 1900, McClure's decided to expose problems in American society. They looked into big businesses, or "trusts." They chose to focus on the oil industry, especially Standard Oil, partly because Ida Tarbell had grown up in the oil fields.

Tarbell began a detailed investigation into Standard Oil and its founder, John D. Rockefeller. Her father worried that Rockefeller would try to stop her. One of Rockefeller's banks even threatened the magazine's finances, but Tarbell wasn't scared.

Tarbell developed new investigative techniques. She searched through old documents and interviewed people across the country. She found proof that Standard Oil used aggressive and unfair tactics to control the oil business. Her findings became a powerful story about big business.

A key discovery was a rare book called The Rise and Fall of the South Improvement Company. Standard Oil had tried to destroy all copies of this book, which revealed the company's illegal beginnings. Tarbell found one copy in the New York Public Library.

Another important clue came from an office boy at Standard Oil. He found documents showing that railroads were giving Standard Oil secret information about its competitors. He gave these papers to his Sunday school teacher, who then passed them to Tarbell.

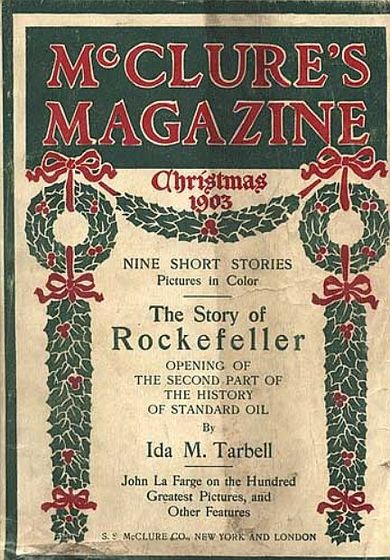

Tarbell's investigative reports on Standard Oil were published as a series of 19 articles in McClure's from 1902 to 1904. These articles, along with others by Lincoln Steffens and Ray Stannard Baker, started the era of "muckraking" journalism.

The series was a huge success. It helped lead to the breakup of Standard Oil and new laws like the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914. Tarbell never met or spoke to Rockefeller, who reportedly called her "Miss Tarbarrel."

President Theodore Roosevelt gave Tarbell and other investigative journalists the name "muckrakers." He meant they were like someone constantly raking up dirt. Tarbell didn't like the label. She felt she was a historian, not just someone looking for trouble. She believed her work needed to be balanced and based on facts to create lasting change.

The American Magazine

Ida Tarbell worked for McClure's until 1906. The publisher, S. S. McClure, became difficult to work with. This, along with her father's death, caused her a lot of stress. So, Tarbell and other editors left McClure's.

They bought The American Illustrated Magazine and renamed it The American Magazine. Tarbell became an associate editor. This new magazine focused on what was "right" in society, rather than just exposing problems.

In 1906, Tarbell also bought a farm in Redding, Connecticut, which she named Twin Oaks. Her sister and other family members lived there with her. She often hosted friends, including the famous author Mark Twain.

At The American Magazine, Tarbell wrote important articles about tariffs (taxes on imported goods) and their effect on businesses. She also visited Hull House in Chicago, a famous settlement house, where she saw programs that helped immigrant women.

In 1911, Tarbell and the other editors sold The American Magazine. Tarbell then became a freelance writer. She wrote a series of articles about the good side of American business. She visited factories and met with owners and workers. She admired people like Henry Ford, who believed in paying workers well and using efficient production methods.

Views on Women's Rights

Ida Tarbell was a strong woman who achieved a lot, but her views on women's rights were complex. She was a "feminist by example," meaning her actions showed women's capabilities, but she didn't always agree with the feminist movement's ideas.

Early in life, she saw her mother host meetings for women's suffrage (the right to vote). But Tarbell felt that the women involved didn't pay attention to her, while the men her father hosted did.

Starting around 1909, Tarbell wrote more about women's traditional roles. She felt that the suffrage movement was too aggressive and "anti-male." She believed women should focus on home life and family. Her book, The Business of Being a Woman, which expressed these views, was not well-received by many women's rights supporters. Even her own mother, a lifelong suffragette, disagreed with Ida's stance.

However, after American women won the right to vote in 1920, Tarbell changed her mind. She wrote an article in 1924 encouraging women to vote. When asked if a woman could be president, she pointed out that women had ruled nations well throughout history.

Tarbell also worked to help women who had to work, especially in difficult conditions. She wrote about workplace safety and supported "scientific management" methods to protect workers and increase profits.

In 1914, Tarbell helped create the Authors' League (now the Authors Guild), a group to support writers. She also joined the Chautauqua lecture circuit, traveling and speaking across the country on topics like peace, politics, and women's issues.

World War I and Later Life

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson invited Tarbell to join the Women's Committee of the Council of National Defense. This committee helped mobilize American women for the war effort. They encouraged women to plant gardens, preserve food, and make bandages. Tarbell often helped communicate between the men's and women's committees.

In 1917, Tarbell faced personal challenges. Her mother died, and Tarbell herself collapsed and was diagnosed with tuberculosis. She spent three months recovering in the hospital. She also began showing early signs of Parkinson's disease, though she didn't know the diagnosis at the time.

After the war ended in 1918, Tarbell traveled to Paris again. She wrote for the Red Cross magazine, interviewing French people about how the war affected them. She focused on the experiences of average Frenchwomen.

In her later career, Tarbell continued writing, lecturing, and doing social work. She served on two Presidential Conferences, including one on unemployment in 1921. She also wrote her only novel, The Rising of the Tide, in 1919.

Tarbell wrote another biography about Judge Elbert Henry Gary, the head of U.S. Steel. She earned a good fee for the book. Some critics felt she was too kind to big business in this work. She also wrote a flattering profile of Benito Mussolini, comparing him to Napoleon. Her final business biography was about Owen D. Young, the president of General Electric.

Ida Tarbell completed her autobiography, All in a Day's Work, in 1939, when she was 82. She died of pneumonia on January 6, 1944, at the age of 86.

Legacy

Ida Tarbell is remembered for her important contributions to journalism and American history. Experts say she helped invent modern journalism. Her book, The History of the Standard Oil Company, is considered one of the most influential books on business ever published in the United States.

The investigative methods she developed are still used today to train journalists. Unlike "yellow journalists" who focused on sensational stories without checking facts, Tarbell and other "muckrakers" wrote detailed, accurate reports. Their work led to legal changes and set high standards for investigative journalism.

In 1993, her home in Easton, Connecticut, was named a National Historic Landmark. In 2000, she was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame. In 2002, the United States Postal Service honored her with a commemorative stamp.

Writing Style and Methods

Ida Tarbell was known for her hard work and thorough research. Her background in science meant she approached her investigations like a scientist, supporting every statement with facts. Her early works were full of detailed information.

When writing biographies, Tarbell would try to forget everything she knew about the person. This allowed her to see things with fresh eyes. She also included well-chosen stories and personal details to bring her subjects to life. For her Lincoln biography, she interviewed hundreds of people who knew him and found many unpublished documents. She even sent her articles to people whose information she used to double-check for accuracy.

Tarbell's writing was fair and professional. Her methods for researching corporations, using government documents, lawsuits, and interviews, helped her uncover secrets from powerful companies. She liked to work at a desk covered in research materials, whether at home or in her office.

In Other Media

A play called The Lion and the Mouse (1905) opened soon after Tarbell's Standard Oil series was published. Many people thought the play's story was based on her work. It was very popular and set a record for continuous performances in New York.

Selected Works

Books

- A Short Life of Napoleon Bonaparte. New York: S. S. McClure, 1895.

- Madame Roland: a biographical study. New York: Scribner's, 1896.

- Recollections of the Civil War. New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1898, written by Ida Tarbell.

- The Life of Abraham Lincoln. 2 vols. New York: McClure Phillips, 1900.

- A Life of Napoleon Bonaparte: with a sketch of Josephine, Empress of the French New York: Macmillan, 1901.

- The History of the Standard Oil Company, 2 vols. New York: McClure, 1904.

- He Knew Lincoln. New York: Doubleday Page, 1907.

- Father Abraham New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1909.

- The Tariff in Our Times. New York: Macmillan Company, 1911.

- The Business of Being a Woman. New York: Macmillan, 1912.

- The Ways of Woman. New York: Macmillan, 1915.

- New Ideals in Business, An Account of Their Practice and Their Effects upon Men and Profits. New York: Macmillan, 1916.

- The Rising of the Tide; The Story of Sabinsport (novel) New York, Macmillan, 1919.

- In Lincoln's Chair. New York: Macmillan,1920.

- Boy Scouts' Life of Lincoln. New York: Macmillan, 1921.

- He Knew Lincoln, and Other Billy Brown Stories. New York: Macmillan, 1922.

- Peacemakers—Blessed and Otherwise: Observations, Reflections and Irritations at an International Conference. New York: Macmillan, 1922.

- The Life of Elbert H. Gary: The Story of Steel. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1925.

- A Reporter for Lincoln: Story of Henry E. Wing, Soldier and Newspaperman. New York: Book League of America, 1929.

- Owen D. Young: A New Type of Industrial Leader. New York: Macmillan Company, 1932. ISBN: 0-518-19069-2.

- All in the Day's Work: An Autobiography. New York: Macmillan Company, 1939.

See also

In Spanish: Ida Tarbell para niños

In Spanish: Ida Tarbell para niños

- The Hepburn Committee (1879)

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |