Yellow journalism facts for kids

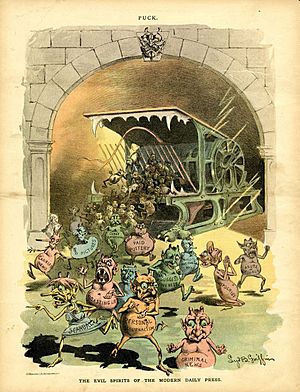

Yellow journalism (also called the yellow press) is a type of journalism that doesn't always share real news or facts. Instead, it uses exciting or shocking headlines to grab people's attention. The main goal is to sell more newspapers. Yellow journalism often makes facts seem bigger than they are. It might even spread rumors that aren't true.

Yellow press newspapers often had many sections. They featured big headlines on the front page about different kinds of news. This included sports and scandals. They used bold designs with large pictures and sometimes color. Stories were often reported using secret sources. This term was used a lot around 1900. It described big New York City newspapers. These papers were fighting to get more readers than their rivals.

In 1941, Frank Mott listed five things that made up yellow journalism:

- Headlines in huge print meant to scare people. These were often about news that wasn't very important.

- Using many pictures or drawings.

- Using fake interviews or headlines that didn't tell the whole truth. They also used pseudoscience (fake science). They would use false information from people who said they were experts.

- Full-color sections in the Sunday newspaper. These usually had comic strips. (This is now normal in the United States).

- Taking the side of the "underdog" (the weaker person or group) against the powerful system.

Contents

How Yellow Journalism Started

The term "yellow journalism" came from the American Gilded Age. This was in the late 1800s. Two newspaper owners were fighting to get more readers. These were Joseph Pulitzer with the New York World and William Randolph Hearst with the New York Journal. Their biggest fight was from 1895 to about 1898. When people talk about "yellow journalism" in history, they often mean these years.

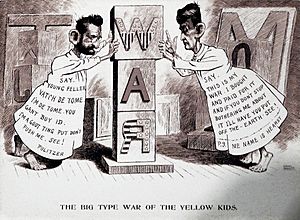

Both newspapers were accused of making news seem much more important than it was. This was done to sell more copies. However, both newspapers also did serious reporting. The New York Press first used the term "Yellow Kid journalism" in early 1897. This was named after a popular comic strip. It described the newspapers of Pulitzer and Hearst. Both papers published versions of the comic during their fight for readers. Ervin Wardman, who ran the New York Herald, created the term. His newspaper was not considered "yellow journalism."

Joseph Pulitzer bought the New York World in 1883. He had already made the St. Louis Post-Dispatch the biggest newspaper in that city. Pulitzer wanted to make the New York World fun to read. He filled his paper with pictures, games, and contests. This helped bring in many new readers.

The New York World had many exciting stories. But these were not the only stories, or even the most important ones. Pulitzer believed that newspapers were important. He felt they had a duty to make society better. He tried to do this with his newspaper.

Just two years after Pulitzer took over, the World sold more copies than any other newspaper in New York. This was partly because he was connected to the Democratic Party. Older newspaper owners were jealous of Pulitzer's success. They started saying bad things about the World. They talked about his crime stories and stunts. But they ignored his more serious reporting. Charles Dana, the editor of the New York Sun, criticized The World. He said Pulitzer lacked good judgment.

William Randolph Hearst was a rich heir from mining. He bought the San Francisco Examiner from his father in 1887. Hearst noticed what Pulitzer was doing. He had read the World while studying at Harvard University. He decided to make the Examiner as exciting as Pulitzer's paper. While he was in charge, the Examiner used 24 percent of its front page space for crime stories. A month after Hearst took over, the Examiner ran this headline about a hotel fire:

HUNGRY, FRANTIC FLAMES. They Leap Madly Upon the Splendid Pleasure Palace by the Bay of Monterey, Encircling Del Monte in Their Ravenous Embrace From Pinnacle to Foundation. Leaping Higher, Higher, Higher, With Desperate Desire. Running Madly Riotous Through Cornice, Archway and Facade. Rushing in Upon the Trembling Guests with Savage Fury. Appalled and Panic-Striken the Breathless Fugitives Gaze Upon the Scene of Terror. The Magnificent Hotel and Its Rich Adornments Now a Smoldering heap of Ashes. The Examiner Sends a Special Train to Monterey to Gather Full Details of the Terrible Disaster. Arrival of the Unfortunate Victims on the Morning's Train — A History of Hotel del Monte — The Plans for Rebuilding the Celebrated Hostelry — Particulars and Supposed Origin of the Fire.

Hearst could be over the top in his crime stories. One early story about a "band of murderers" criticized the police. It said the police made Examiner reporters do their work for them. But while doing these things, the Examiner also added more international news. It sent reporters to find corruption and problems in the city government. In one story, Examiner reporter Winifred Black pretended to be a patient in a San Francisco hospital. She found that the women there were treated very badly. The entire hospital staff was fired the morning the story was printed.

The New York Newspaper War

By the early 1890s, the Examiner was doing well. Hearst then looked for a New York newspaper to buy. In 1895, he bought the New York Journal. This newspaper sold for one penny. Pulitzer's brother Albert had sold it to a publisher the year before.

Pulitzer kept his newspaper at two cents. Hearst noticed this. So, he made the Journal cost only one cent. He still gave as much information as rival newspapers. This worked, and the Journal gained 150,000 subscribers. Pulitzer then cut his price to a penny. He hoped to make Hearst run out of money. Hearst was supported by his family's wealth. In 1896, Hearst hired many people who worked for the World. Most people say Hearst simply offered more money. But Pulitzer had become very difficult to work for. Many World employees were happy to switch newspapers just to get away from him.

The competition between the World and the Journal was very strong. But the newspapers had a lot in common. Both supported the Democratic Party. Both supported organized labor and immigrants. Other publishers, like New York Tribune's Whitelaw Reid, blamed poverty on moral problems. But Pulitzer and Hearst did not. Both papers spent a lot of money on their Sunday editions. These were like weekly magazines. They went beyond just daily news.

Their Sunday fun pages included the first color comic strips. Some people think the term yellow journalism came from these comics. As mentioned, the New York Press did not fully explain the term it created. Hogan's Alley was a comic strip about a bald child in a yellow nightshirt. He was nicknamed The Yellow Kid. This comic became very popular when Richard F. Outcault started drawing it for the World in early 1896. When Hearst hired Outcault away, Pulitzer asked artist George Luks to keep drawing the strip. This meant the city had two Yellow Kids. The term "yellow journalism" for over-the-top sensationalism likely started with more serious newspapers. They commented on how extreme "the Yellow Kid papers" were.

Yellow Journalism and the Spanish-American War

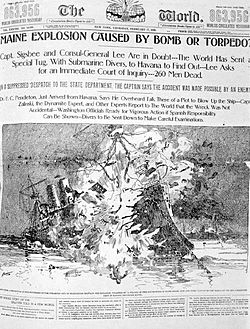

Pulitzer and Hearst are often given credit (or blame) for getting the United States into the Spanish-American War. This was because of their sensational news stories. However, most Americans did not live in New York City. The leaders who did live there probably read less exciting newspapers. These included the Times, The Sun, or the Post. The most famous story of exaggeration is probably not true. It says artist Frederic Remington sent Hearst a telegram. He told Hearst that not much was happening in Cuba and "There will be no war." Hearst supposedly replied, "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war." This story first appeared in reporter James Creelman's memoirs in 1901. There is no other source for it.

But Hearst did want the United States to go to war. A rebellion had started in Cuba in 1895. Stories about Cubans being good people and Spain treating Cuba badly soon appeared on his front page. These stories were probably not very accurate. But newspaper readers in the 1800s did not expect, or necessarily want, stories to be pure facts. Historian Michael Robertson said that "Newspaper reporters and readers of the 1890s were much less concerned with telling the difference between fact-based reporting, opinion, and literature."

Pulitzer did not have as many resources as Hearst. But he kept the story on his front page. The yellow press published a lot about the revolution. Much of it was not completely true. But conditions in Cuba were bad enough. The island was in a severe economic depression. Spanish general Valeriano Weyler was sent to stop the rebellion. He forced Cuban farmers into concentration camps. These were places where many people were held against their will, leading to hundreds of Cubans dying. Hearst had pushed for a war for two years. When it happened, he took credit. A week after the United States declared war on Spain, he printed "How do you like the Journal's war?" on his front page. In reality, President William McKinley never read the Journal. He read newspapers like the Tribune and the New York Evening Post. Also, historians of journalism have noted that yellow journalism mostly happened only in New York City. Newspapers in the rest of the country did not do it. The Journal and the World were not top sources of news in other parts of the country. Their stories did not get much attention outside New York City.

When the invasion began, Hearst sailed to Cuba. He went as a war reporter. He gave calm and accurate reports of the fighting. Creelman later praised the reporters' work. He said they wrote about how Spain treated Cuba. He argued, "no true history of the war . . . can be written without saying that any justice, freedom, and progress from the Spanish-American war was due to the hard work of yellow journalists. Many of them lie in forgotten graves."

After the War

Hearst was a well-known Democrat. He supported William Jennings Bryan for president in 1896 and 1900. (Bryan did not win either election). Hearst later ran for mayor and governor. He even tried to be nominated for president. But his reputation was hurt in 1901. Columnist Ambrose Bierce and editor Arthur Brisbane published separate articles. These articles, months apart, suggested that President William McKinley should be attacked. When McKinley was shot on September 6, 1901, critics blamed Hearst's Yellow Journalism. They said it influenced Leon Czolgosz to do the deed. Hearst did not know about Bierce's article. He claimed to have removed Brisbane's article after it appeared in an early edition. But this event would affect him for the rest of his life. It almost destroyed his dream of becoming president.

Pulitzer was troubled by what had happened. He made the World return to its serious reporting roots as the new century began. By the time he died in 1911, the World was a highly respected newspaper. It remained a leading progressive paper until it closed in 1931.

See also

In Spanish: Prensa amarilla para niños

In Spanish: Prensa amarilla para niños