Women's suffrage in the United States facts for kids

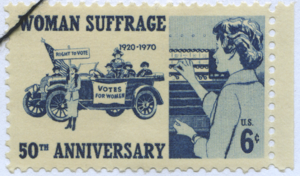

Women's suffrage is the right for women to vote. In the United States, women gained this right over many years, from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. It started in different states and towns. Finally, in 1920, it became a national law with the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The idea of women voting started to become popular in the 1840s. It grew out of a larger movement for women's rights. In 1848, the first women's rights meeting, called the Seneca Falls Convention, decided that women should have the right to vote. Some organizers thought this idea was too extreme at first. But by 1850, at the first National Women's Rights Convention, voting rights became a very important part of the movement.

The first national groups focused on women's voting rights started in 1869. Two different groups were formed. One was led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The other was led by Lucy Stone and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. After many years, these groups joined together in 1890. They became the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Susan B. Anthony was a main leader of this new group. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), a large women's group formed in 1873, also supported women's voting rights. This gave a huge boost to the movement.

In the early 1870s, women who supported voting rights tried to vote. They hoped the U.S. Supreme Court would say women had a constitutional right to vote. When they were turned away, they filed lawsuits. Susan B. Anthony actually voted in 1872 but was arrested. Her trial was very public and helped the movement gain more support. After the Supreme Court ruled against them in 1875, these women started a long campaign. They worked for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would give women the right to vote. However, much of their effort also went into getting voting rights state by state.

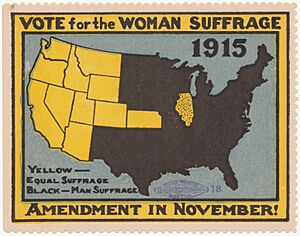

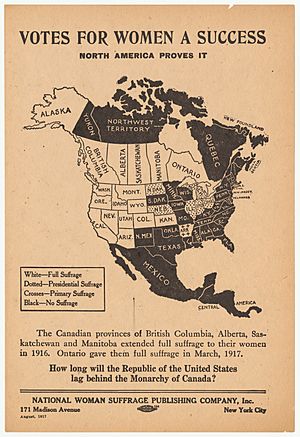

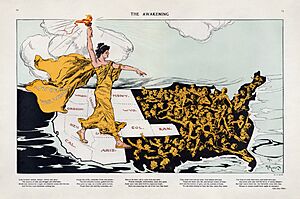

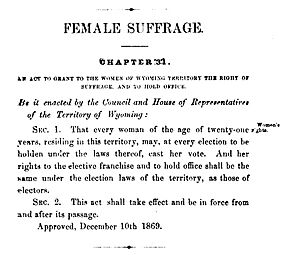

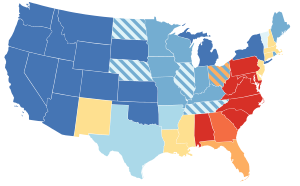

The first state to give women the right to vote was Wyoming in 1869. Then came Utah in 1870, Colorado in 1893, and Idaho in 1896. More states followed, including Washington (1910), California (1911), Oregon and Arizona (1912), Montana (1914), North Dakota, New York, and Rhode Island (1917), and Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Michigan (1918).

In 1916, Alice Paul started the National Woman's Party (NWP). This group focused on getting a national amendment for voting rights. In 1917, over 200 NWP supporters, called the Silent Sentinels, were arrested for protesting outside the White House. Some went on hunger strike and were force-fed in prison. The two-million-member NAWSA, led by Carrie Chapman Catt, also made a national voting rights amendment their top goal. After many votes in the U.S. Congress and state legislatures, the Nineteenth Amendment became part of the U.S. Constitution on August 18, 1920. It says: "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or limited by the United States or by any State because of sex."

Contents

- The Fight for Women's Voting Rights

- Early History of Voting in the U.S.

- How the Women's Rights Movement Began

- Anthony and Stanton Work Together

- Women's Loyal National League

- American Equal Rights Association

- New England Woman Suffrage Association

- The Fifteenth Amendment and the Split

- The "New Departure" Strategy

- Susan B. Anthony's Trial

- History of Woman Suffrage

- The Women's Suffrage Amendment is Introduced

- Early Women Running for National Office

- First Wins and Losses

- The Years 1890–1919

- Rival Voting Rights Groups Merge

- National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA)

- Opposition to Women's Voting Rights

- Southern Strategy for Voting Rights

- Fighting Against Racism in the Movement

- The "New Woman" and Public Action

- New Voting Rights Organizations

- Voting Rights Newspapers

- The Tide Turns for Women's Voting Rights

- The Nineteenth Amendment Passes

- What Changed After the Nineteenth Amendment?

- More to Explore

The Fight for Women's Voting Rights

Early History of Voting in the U.S.

Most early U.S. states, following old traditions from when they were British colonies, had laws that clearly said women could not vote. This was based on old ideas about society and laws. For example, during the Middle Ages, a law called coverture meant that a married woman had no legal identity of her own. She was legally seen as one with her husband.

When Women Could Vote Early On

Lydia Taft (1712–1778), a wealthy widow, was allowed to vote in town meetings in Uxbridge, Massachusetts in 1756. She is the only woman known to have voted in the colonial era.

The New Jersey constitution of 1776 allowed all adult property owners to vote, whether "he or she." Women regularly voted there. However, a law in 1807 stopped women from voting in New Jersey.

Kentucky passed the first statewide law allowing women to vote in 1838. This was after New Jersey took away women's voting rights. This law allowed any widow or single woman (who was the head of her household) over 21 to vote in school elections if she owned property and lived in the county. This right was not just for white women.

How the Women's Rights Movement Began

The demand for women's voting rights grew from a larger movement for women's rights. In 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft wrote an important book in the UK called A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. In the U.S., Sarah Grimké published The Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women in 1838, which was widely read. In 1845, Margaret Fuller published Woman in the Nineteenth Century, a key document in American feminism.

There were big challenges to overcome before the campaign for women's voting rights could become strong. One challenge was the strong opposition to women being involved in public life. Even among people who wanted reforms, it was not fully accepted. For example, women were only accepted as members of the American Anti-Slavery Society after a big debate in 1839.

People especially disliked the idea of women speaking to audiences of both men and women. Frances Wright, a Scottish woman, was heavily criticized for giving public talks in the U.S. in 1826 and 1827. When the Grimké sisters, who grew up in a slave-owning family, spoke against slavery in the 1830s, church leaders in that region condemned their actions. Despite this, in 1838, Angelina Grimké spoke against slavery to the Massachusetts legislature. She was the first woman in the U.S. to speak before a lawmaking body.

Other women then started giving public speeches. They spoke against slavery and for women's rights. Early female speakers included Ernestine Rose, Lucretia Mott, and Abby Kelley Foster. By the late 1840s, Lucy Stone became a famous public speaker. She supported both the anti-slavery and women's rights movements. Stone helped reduce the prejudice against women speaking in public.

But strong opposition remained. A women's rights meeting in Ohio in 1851 was interrupted by men who opposed it. Sojourner Truth, who gave her famous speech "Ain't I a Woman?" at that meeting, directly addressed some of this opposition. The National Women's Rights Convention in 1852 was also disrupted. At the 1853 convention, a mob almost turned violent. A big meeting about temperance in New York City in 1853 was stuck for three days because of a fight over whether women could speak.

Susan B. Anthony, a leader of the voting rights movement, later said, "No step forward taken by women has been so strongly fought as that of speaking in public. For nothing they have tried, not even to get the right to vote, have they been so badly treated, condemned, and opposed."

Laws that greatly limited what married women could do also made it hard for the voting rights campaign. An old English law called coverture meant that when a woman married, her legal existence was "suspended." In 1862, a judge in North Carolina refused a divorce to a woman whose husband had whipped her. He said, "The law gives the husband power to use such force as needed to make the wife behave and know her place." In many states, married women could not legally sign contracts. This made it hard for them to arrange meeting halls or print materials for the movement. These limits were partly overcome when several states passed laws allowing married women to own property. Wealthy fathers sometimes supported these laws so their daughters' money would not be fully controlled by their husbands.

The idea of women's rights was strong among the radical anti-slavery groups. William Lloyd Garrison, a leader of the American Anti-Slavery Society, said, "I doubt whether a more important movement has been launched concerning the future of humanity, than this one about the equality of the sexes." However, the anti-slavery movement only included about one percent of the population at that time, and radical abolitionists were only a small part of that movement.

Early Support for Women's Voting Rights

The New York State Constitutional Convention of 1846 received requests from people in at least three counties who supported women's voting rights.

Some members of the radical anti-slavery movement supported voting rights for women. In 1846, Samuel J. May, a minister and abolitionist, strongly supported women's voting rights in a sermon. This sermon was later shared widely as one of the first writings on women's rights. In 1846, the Liberty League, a group connected to the anti-slavery Liberty Party, asked Congress to give women the right to vote. A meeting of the Liberty Party in Rochester, New York in May 1848 approved a resolution calling for "universal suffrage in its broadest sense, including women as well as men." Gerrit Smith, their candidate for president, spoke about his party's call for women's voting rights. Lucretia Mott was even suggested as the party's vice-presidential candidate. This was the first time a woman was proposed for a high federal office in the U.S.

First Women's Rights Meetings

At this time, women's voting rights were not a main topic in the women's rights movement. Many activists believed they should avoid political action and instead try to convince people with "moral persuasion." Many were Quakers, whose traditions kept both men and women from secular political activity. A series of women's rights meetings helped change these attitudes.

Seneca Falls Convention

The first women's rights meeting was the Seneca Falls Convention. It was a local event held on July 19 and 20, 1848, in Seneca Falls, New York. Five women organized the meeting. Four were Quaker social activists, including the well-known Lucretia Mott. The fifth was Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who had talked with Mott about organizing for women's rights years earlier. Stanton, whose family was involved in politics, became a key person in convincing the women's movement that political pressure was vital. She believed the right to vote was a crucial tool. About 300 women and men attended this two-day event, which was widely reported in newspapers.

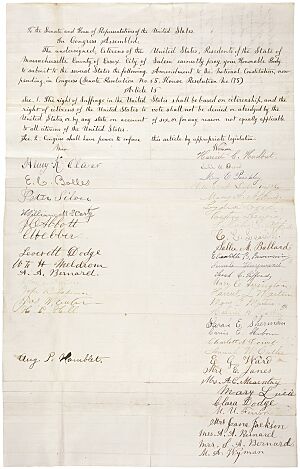

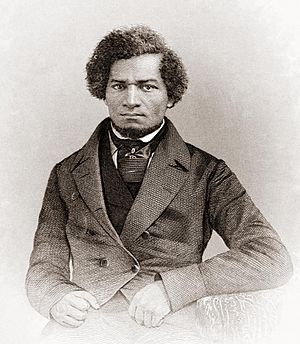

The only resolution not passed by everyone at the meeting was the one demanding women's right to vote. Stanton introduced it. Her husband, a well-known reformer, refused to attend and said she was making the meeting a joke. Lucretia Mott, a main speaker, was also worried about the idea. The resolution passed only after Frederick Douglass, a leader against slavery and a former slave, strongly supported it. The meeting's Declaration of Sentiments, mostly written by Stanton, aimed to build a women's rights movement. It listed complaints, and the first two protested the lack of women's voting rights. These complaints, aimed at the U.S. government, "demanded government reform and changes in male roles and behaviors that promoted inequality for women."

This meeting was followed two weeks later by the Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848. It had many of the same speakers and also voted to support women's voting rights. It was the first women's rights meeting led by a woman, which was seen as a very bold step at the time. That meeting was followed by the Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850, the first statewide women's rights meeting, which also supported women's voting rights.

National Conventions for Women's Rights

The first in a series of National Women's Rights Conventions was held in Worcester, Massachusetts on October 23–24, 1850. It was started by Lucy Stone and Paulina Wright Davis.

National conventions were held almost every year until 1860, when the Civil War (1861–1865) stopped them. Voting rights became a top goal at these conventions. It was no longer the controversial issue it had been at Seneca Falls just two years earlier. At the first national convention, Stone gave a speech that included a call to ask state legislatures for the right to vote.

News of this convention reached Britain. This led Harriet Taylor, who would soon marry philosopher John Stuart Mill, to write an essay called "The Enfranchisement of Women." It was published in the Westminster Review. Taylor's essay praised the women's movement in the U.S. and helped start a similar movement in Britain. Her essay was reprinted in the U.S. and sold for decades.

Wendell Phillips, a famous abolitionist and women's rights supporter, gave a speech at the second national convention in 1851 called "Shall Women Have the Right to Vote?" He said women's voting rights were the most important part of the women's movement. This speech was later shared widely.

Several women who led the national conventions, especially Stone, Anthony, and Stanton, also helped start women's voting rights groups after the Civil War. They also included the demand for voting rights in their activities during the 1850s. In 1852, Stanton spoke at the New York State Temperance Convention, supporting women's voting rights. In 1853, Stone became the first woman to ask lawmakers for women's voting rights when she spoke to the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention. In 1854, Anthony organized a petition campaign in New York State that included the demand for voting rights. It ended with a women's rights convention in the state capital and a speech by Stanton to the state legislature. In 1857, Stone refused to pay taxes because women were taxed without being able to vote on tax laws. A constable sold her household goods at auction to pay her tax bill.

The women's rights movement was loosely organized during this time. There were few state groups and no national group other than a committee that arranged the yearly national conventions. Much of the organizing for these conventions was done by Stone, who was the most visible leader of the movement then. At the national convention in 1852, a suggestion was made to form a national women's rights organization. But the idea was dropped because people worried it would create too much bureaucracy and lead to internal fights.

Anthony and Stanton Work Together

Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton met in 1851. They quickly became close friends and co-workers. Their work together for decades was key for the voting rights movement. It also greatly helped the larger fight for women's rights, which Stanton called "the greatest revolution the world has ever known or ever will know." They had different strengths: Anthony was great at organizing, while Stanton was good at thinking and writing. Stanton, who was at home with several children during this time, wrote speeches that Anthony delivered at meetings she organized. Together, they built a strong movement in New York State. But their work at this time was about women's issues in general, not just voting rights. Anthony, who later became the person most linked to women's voting rights, said, "I wasn't ready to vote, didn't want to vote, but I did want equal pay for equal work." Before the Civil War, Anthony focused more on anti-slavery work than on the women's movement.

Women's Loyal National League

Despite Anthony's concerns, leaders of the movement agreed to pause women's rights activities during the Civil War. They wanted to focus on ending slavery. In 1863, Anthony and Stanton organized the Women's Loyal National League. This was the first national women's political group in the U.S. It collected almost 400,000 signatures on petitions to end slavery. This was the largest petition drive in the nation's history up to that time.

Even though it wasn't a voting rights group, the League clearly supported political equality for women. It helped the cause in several ways. Stanton reminded the public that petitioning was the only political tool women had when only men could vote. The League's impressive petition drive showed the value of formal organization to the women's movement, which had usually avoided strict structures. It also showed a shift in women's activism from moral persuasion to political action. Its 5,000 members created a wide network of women activists. They gained experience that helped create a group of talented people for future social activism, including voting rights.

American Equal Rights Association

The Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention, the first since the Civil War, was held in 1866. It helped the women's rights movement regain its strength. The convention voted to become the American Equal Rights Association (AERA). Its goal was to campaign for equal rights for all citizens, especially the right to vote.

Besides Anthony and Stanton, who organized the convention, the new group's leaders included famous abolitionist and women's rights activists like Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, and Frederick Douglass. However, their push for universal suffrage (voting rights for everyone) was opposed by some abolitionist leaders and their allies in the Republican Party. These people wanted women to wait for their voting rights until African American men had first achieved theirs. Horace Greeley, a well-known newspaper editor, told Anthony and Stanton, "This is a critical time for the Republican Party and the life of our Nation... I beg you to remember that this is 'the black man's hour,' and your first duty now is to go through the State and argue for his rights." But they and others, including Lucy Stone, refused to wait. They continued to push for voting rights for everyone.

In April 1867, Stone and her husband, Henry Blackwell, started the AERA campaign in Kansas. They supported votes in that state that would give voting rights to both African Americans and women. Wendell Phillips, an abolitionist leader who opposed mixing these two causes, surprised and angered AERA workers. He blocked the money the AERA expected for their campaign. After an internal struggle, Kansas Republicans decided to support voting rights only for black men. They formed an "Anti-Female Suffrage Committee" to oppose the AERA's efforts. By the end of summer, the AERA campaign had almost failed, and its money was gone. Anthony and Stanton were strongly criticized by Stone and other AERA members. This was because they accepted help during the last days of the campaign from George Francis Train, a rich businessman who supported women's rights. Train angered many activists by attacking the Republican Party, which many reformers supported. He also openly spoke badly about the honesty and intelligence of African Americans.

After the Kansas campaign, the AERA split into two parts. Both supported universal voting rights but had different ways of achieving it. One part, led by Lucy Stone, was willing for black men to get voting rights first, if needed. They wanted to stay close to the Republican Party and the abolitionist movement. The other part, led by Anthony and Stanton, insisted that women and black men get voting rights at the same time. They worked towards a politically independent women's movement that would no longer rely on abolitionists for money or other help. The angry annual meeting of the AERA in May 1869 showed the end of the organization. After this, two competing women's voting rights groups were created.

New England Woman Suffrage Association

Partly because of the growing split in the women's movement, the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA) was formed in 1868. This was the first major political group in the U.S. with women's voting rights as its main goal. The people who planned the NEWSA's first meeting worked to get Republican support. They seated leading Republican politicians, including a U.S. senator, on the speaker's platform. People were becoming more confident that the Fifteenth Amendment, which would give black men the right to vote, would pass. Lucy Stone, who would later become president of the NEWSA, showed her preference for giving voting rights to both women and African Americans. She unexpectedly introduced a resolution asking the Republican Party to "drop its slogan of 'Manhood Suffrage'" and support universal suffrage instead. Despite opposition from Frederick Douglass and others, Stone convinced the meeting to approve the resolution. However, two months later, when the Fifteenth Amendment was in danger of getting stuck in Congress, Stone changed her position. She declared that "Woman must wait for the Negro."

The Fifteenth Amendment and the Split

In May 1869, two days after the last AERA meeting, Anthony, Stanton, and others formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In November 1869, Lucy Stone, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Julia Ward Howe, Henry Blackwell, and others formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Many of them had helped create the New England Woman Suffrage Association a year earlier. The strong rivalry between these two groups lasted for decades.

The immediate reason for the split was the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This amendment would stop states from denying the right to vote based on race. The original idea for the amendment included a rule against voting discrimination based on sex, but this was later removed. Stanton and Anthony opposed its passage unless another amendment was added that would stop denying voting rights based on sex. They said that by giving all men the right to vote while excluding all women, the amendment would create an "aristocracy of sex." This would give constitutional power to the idea that men were better than women. Stanton argued that male power and privilege were at the root of society's problems, and nothing should be done to make it stronger. Anthony and Stanton also warned that black men, who would gain voting power under the amendment, were mostly against women's voting rights. They were not alone in being unsure of black male support for women's voting rights. Frederick Douglass, a strong supporter of women's voting rights, said, "The race to which I belong has not generally taken the right stand on this question." However, Douglass strongly supported the amendment, saying it was a matter of life and death for former slaves. Lucy Stone, who became the AWSA's most important leader, supported the amendment. But she said she believed that voting rights for women would be more helpful to the country than voting rights for black men. The AWSA and most AERA members also supported the amendment.

Both parts of the movement were strongly against slavery. But their leaders sometimes said things that showed the racial attitudes of that time. Stanton, for example, believed that a long process of education would be needed before what she called the "lower orders" of former slaves and immigrant workers could truly participate as voters. In a newspaper article, Stanton wrote, "American women of wealth, education, virtue and refinement, if you do not wish the lower orders of Chinese, Africans, Germans and Irish, with their low ideas of womanhood to make laws for you and your daughters ... demand that women too shall be represented in government." Lucy Stone asked at a meeting in New Jersey, "Shall women alone be left out in the reconstruction? Shall [they] ... be ranked politically below the most ignorant and degraded men?"

The AWSA wanted close ties with the Republican Party. They hoped that once the Fifteenth Amendment passed, Republicans would push for women's voting rights. The NWSA, while wanting to be politically independent, criticized the Republicans. Anthony and Stanton wrote a letter to the 1868 Democratic National Convention. They criticized Republican support of the Fourteenth Amendment (which gave citizenship to black men but for the first time used the word "male" in the Constitution). They said, "While the powerful party has with one hand lifted up two million black men and given them the honor and dignity of citizenship, with the other it has removed fifteen million white women—their own mothers and sisters, their own wives and daughters—and put them under the control of the lowest men." They urged liberal Democrats to convince their party to support universal voting rights.

The two groups also had other differences. Both campaigned for voting rights at state and national levels. But the NWSA tended to work more at the national level, and the AWSA more at the state level. The NWSA first worked on more issues than the AWSA, like divorce reform and equal pay for women. The NWSA was led only by women, while the AWSA included both men and women among its leaders.

Events soon made much of the reason for the split less important. In 1870, the debate about the Fifteenth Amendment ended when it was officially passed. In 1872, anger about government corruption led many abolitionists and other reformers to leave the Republicans and join the short-lived Liberal Republican Party. However, the rivalry between the two women's groups was so strong that they could not merge until 1890.

The "New Departure" Strategy

In 1869, Francis and Virginia Minor, a husband and wife who supported voting rights from Missouri, came up with a plan called the New Departure. This plan involved the voting rights movement for several years. They argued that the U.S. Constitution already gave women the right to vote without needing a new amendment. This strategy relied heavily on Section 1 of the recently passed Fourteenth Amendment. This section says: "All persons born or naturalized in the United States...are citizens...No State shall make or enforce any law which shall limit the privileges or immunities of citizens..."

In 1871, the NWSA officially adopted the New Departure strategy. They encouraged women to try to vote and to file lawsuits if they were stopped. Soon, hundreds of women tried to vote in many places. In some cases, actions like these happened before the New Departure strategy. In 1868 in Vineland, New Jersey, almost 200 women put their ballots into a separate box and tried to have them counted, but it didn't work. The AWSA did not officially adopt the New Departure strategy, but Lucy Stone, its leader, tried to vote in her hometown in New Jersey. In one court case from a lawsuit by women who were stopped from voting, a U.S. court ruled that women did not have an automatic right to vote. It said, "The fact that the practical working of the assumed right would destroy civilization is proof that the right does not exist."

In 1871, Victoria Woodhull, a stockbroker, was invited to speak before a committee of Congress. She was the first woman to do so. She had little connection to the women's movement before this. She presented a changed version of the New Departure strategy. Instead of asking courts to say women had the right to vote, she asked Congress itself to declare that the Constitution already gave women the right to vote. The committee rejected her idea. The NWSA at first was excited about Woodhull's sudden appearance. Stanton especially liked Woodhull's idea to create a broad reform party that would support women's voting rights. Anthony opposed that idea, wanting the NWSA to stay politically independent.

The Supreme Court ended the New Departure strategy in 1875. In the case of Minor v. Happersett, the Court ruled that "the Constitution of the United States does not give the right of suffrage to anyone." The NWSA then decided to pursue the much harder strategy of campaigning for a constitutional amendment that would guarantee voting rights for women.

Susan B. Anthony's Trial

In a case that caused national debate, Susan B. Anthony was arrested for breaking the law by voting in the 1872 presidential election. At her trial, the judge told the jury to find her guilty. When he asked Anthony, who had not been allowed to speak during the trial, if she had anything to say, she gave what one historian called "the most famous speech in the history of the fight for woman suffrage." She called it "this high-handed outrage upon my citizen's rights," saying, "... you have stepped on every important principle of our government. My natural rights, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights, are all ignored." The judge ordered Anthony to pay a fine of $100. She replied, "I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty," and she never did. However, the judge did not order her to be imprisoned until she paid the fine, so Anthony could not appeal her case. On August 18, 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump officially pardoned Anthony after her death, on the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment.

History of Woman Suffrage

In 1876, Anthony, Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage started working on the History of Woman Suffrage. They first thought it would be a small book made quickly. But it grew into a six-volume work of over 5,700 pages, written over 41 years. Its last two volumes were published in 1920, long after the original authors had died, by Ida Husted Harper, who also helped with the fourth volume. This history was written by leaders of one part of the divided women's movement. Lucy Stone, their main rival, refused to be involved. The History of Woman Suffrage saved a huge amount of information that might have been lost. However, it does not give a balanced view of events when it talks about their rivals. For many years, it was the main source of information about the voting rights movement. Because of this, historians have had to find other sources to get a more balanced view.

The Women's Suffrage Amendment is Introduced

In 1878, Senator Aaron A. Sargent, a friend of Susan B. Anthony, introduced a women's voting rights amendment to Congress. More than forty years later, it would become the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution with no changes to its words. Its text is the same as the Fifteenth Amendment, except it stops the denial of voting rights because of sex, instead of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." Even though he was a politician who usually followed party lines, Sargent always supported women's rights. He spoke at voting rights meetings and helped pass laws for suffrage.

Early Women Running for National Office

Elizabeth Cady Stanton pointed out the strange situation of being legally allowed to run for office but denied the right to vote. She declared herself a candidate for the U.S. Congress in 1866, the first woman to do so. In 1872, Victoria Woodhull formed her own party and said she was its candidate for President of the U.S. even though she was too young (not yet 35).

In 1884, Belva Ann Lockwood, the first female lawyer to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court, became the first woman to run a serious campaign for president. A California group called the Equal Rights Party nominated her without her knowing beforehand. Lockwood supported women's voting rights and other reforms during her campaign across the country. She received respectful coverage from some major newspapers. She paid for her campaign partly by charging admission to her speeches. Neither the AWSA nor the NWSA, both of whom had already supported the Republican candidate for president, supported Lockwood's campaign.

Besides running for national office, many women were elected or appointed to other offices across the country before the Nineteenth Amendment passed. Many state constitutions had gender-neutral language about holding office. Women used this to run for office as a way to make progress in gaining the right to vote. Much of women's fight to gain office-holding rights and voting rights happened separately. Many people saw them as completely different rights.

First Wins and Losses

Women gained voting rights in frontier Wyoming Territory in 1869 and in Utah in 1870. Because Utah held two elections before Wyoming, Utah became the first place in the nation where women legally voted after the suffrage movement began. In 1887, Kansas women could vote in city elections and hold certain offices. The short-lived Populist Party supported women's voting rights. This helped women gain voting rights in Colorado in 1893 and Idaho in 1896. In some places, women gained some voting rights, like voting for school boards. A 2018 study found that states with large voting rights movements and competitive political environments were more likely to give women voting rights. This is one reason why Western states adopted women's voting rights faster than Eastern states.

In the late 1870s, the voting rights movement got a big boost. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the largest women's group in the country, decided to campaign for voting rights. They created a special department to support this effort. Frances Willard, its pro-suffrage leader, urged WCTU members to seek the right to vote as a way to protect their families from bad habits. In 1886, the WCTU sent petitions with 200,000 signatures to Congress supporting a national voting rights amendment. In 1885, the Grange, a large farmers' group, officially supported women's voting rights. In 1890, the American Federation of Labor, a large labor group, supported women's voting rights and later collected 270,000 names on petitions for that goal.

A proposed 16th amendment, giving the vote to women, was introduced in 1869 and defeated by the Senate in 1887. Between 1870 and 1890, women's voting rights amendments were defeated by public vote in eight states.

The Years 1890–1919

Rival Voting Rights Groups Merge

The AWSA, which was especially strong in New England, was at first the larger of the two rival voting rights groups. But its strength decreased during the 1880s. Stanton and Anthony, the main figures in the competing NWSA, were more widely known as leaders of the women's voting rights movement during this time. They were also more influential in guiding its direction. They sometimes used bold tactics. For example, Anthony interrupted the official ceremonies for the 100th anniversary of the U.S. Declaration of Independence to present the NWSA's Declaration of Rights for Women. The AWSA refused to be involved in this action.

Over time, the NWSA became more like the AWSA. It focused less on protests and more on being seen as respectable. It also stopped promoting a wide range of reforms. The NWSA's hopes for a federal voting rights amendment were crushed when the Senate voted against it in 1887. After that, the NWSA put more effort into campaigning at the state level, just as the AWSA was already doing. However, working at the state level also had its difficulties. Between 1870 and 1910, the voting rights movement ran 480 campaigns in 33 states just to get the issue of women's voting rights put before voters. These campaigns only resulted in the issue actually being on the ballot 17 times. These efforts led to women getting the right to vote in only two states: Colorado and Idaho.

Alice Stone Blackwell, daughter of AWSA leaders Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, was a major help in bringing the rival voting rights leaders together. She suggested a joint meeting in 1887 to talk about merging. Anthony and Stone liked the idea, but opposition from several NWSA veterans delayed the move. In 1890, the two organizations merged as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Stanton was president of the new group, and Stone was chair of its executive committee. But Anthony, who was vice president, was its leader in practice. She became president herself in 1892 when Stanton retired.

National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA)

Even though Anthony was the main force in the newly merged group, it did not always follow her lead. In 1893, the NAWSA voted, against Anthony's wishes, to hold its annual conventions in Washington and other parts of the country. Anthony's NWSA had always held its conventions in Washington to keep the focus on a national voting rights amendment. She argued against this decision, saying she feared, correctly, that the NAWSA would focus on state-level work instead of national work.

Stanton, who was old but still very radical, did not fit well into the new organization, which was becoming more conservative. In 1895, she published The Woman's Bible, a controversial best-seller that criticized how the Bible was used to make women seem inferior. The NAWSA voted to say it had no connection with the book, even though Anthony thought it was unnecessary and hurtful. Stanton then felt more and more distant from the voting rights movement.

The voting rights movement became less active in the years right after the 1890 merger. When Carrie Chapman Catt was made head of the NAWSA's Organization Committee in 1895, it was unclear how many local chapters the group had or who their leaders were. Catt started to make the organization stronger. She created a work plan with clear goals for every state each year. Anthony was impressed and arranged for Catt to take over as president of the NAWSA when she retired in 1900. In her new role, Catt continued to try to change the disorganized group into one that could lead a major voting rights campaign.

Catt noticed the fast-growing women's club movement. These clubs were filling some of the gap left by the decline of the temperance movement. Local women's clubs at first were mostly reading groups focused on books. But they increasingly became groups of middle-class women meeting in each other's homes weekly to improve their communities. Their national organization was the General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC), founded in 1890. The clubs avoided controversial issues that would divide members, especially religion and alcohol prohibition. In the South and East, voting rights were also very divisive. But there was little resistance to it among clubwomen in the West. In the Midwest, club women at first avoided the voting rights issue carefully. But after 1900, they increasingly came to support it. Catt started what was called the "society plan." This was a successful effort to get wealthy members of the women's club movement to join. Their time, money, and experience could help build the voting rights movement. By 1914, women's voting rights were supported by the national General Federation of Women's Clubs.

Catt resigned her position after four years. This was partly because her husband's health was getting worse and partly to help organize the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. This group was created in Berlin, Germany, in 1904, with Catt as president. In 1904, Anna Howard Shaw, another person Anthony had mentored, was elected president of the NAWSA. Shaw was an energetic worker and a talented speaker, but not a good manager. Between 1910 and 1916, the NAWSA's national board had constant problems that threatened the organization's existence.

Even though its membership and money were at all-time highs, the NAWSA decided to replace Shaw. They brought Catt back as president in 1915. Catt was allowed by the NAWSA to choose her own executive board, which had previously been elected by the organization's annual meeting. Catt quickly changed the loosely structured organization into a very centralized one.

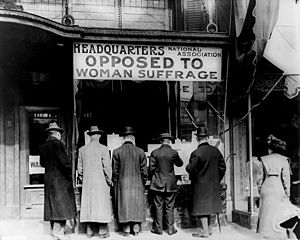

Opposition to Women's Voting Rights

On November 5, 1895, Massachusetts held a public vote on allowing women to vote in city elections. The vote failed, with 36.76% for and 63.24% against. Women were allowed to vote on the measure, but only 4% of them did so.

Brewers and distillers, often from the German-American community, opposed women's voting rights. They feared that women voters would support the prohibition of alcoholic beverages. This fear was justified. During the 1896 election, women's voting rights and prohibition were linked. This was brought to the attention of those who opposed both. To disrupt the campaign's success, the day before the election, the Liquor Dealers' League gathered some businessmen. They tried to make sure some women acted badly in Oakland, California, to hurt the reputation of women who supported voting rights. This would lessen the chances of the amendment passing. German Lutherans and German Catholics usually opposed prohibition and women's voting rights. They preferred families where the husband made decisions about public matters. Their opposition to women's voting rights was later used as an argument in favor of suffrage when German Americans became disliked during World War I.

Defeats could lead to claims of cheating. After the defeat of the women's voting rights vote in Michigan in 1912, the governor accused brewers of being involved in widespread election fraud that caused its defeat. Evidence of vote stealing was also strong during votes in Nebraska and Iowa.

Some other businesses, like Southern cotton mills, opposed voting rights. They feared that women voters would support efforts to end child labor. Political groups, like Tammany Hall in New York City, opposed it. They feared that adding female voters would weaken their control over groups of male voters. However, by the time of the New York State vote on women's voting rights in 1917, some wives and daughters of Tammany Hall leaders were working for suffrage. This led Tammany Hall to take a neutral position, which was crucial for the vote to pass. Although the Catholic Church did not take an official stand on voting rights, very few of its leaders supported it. Some, like Cardinal Gibbons, clearly showed their opposition.

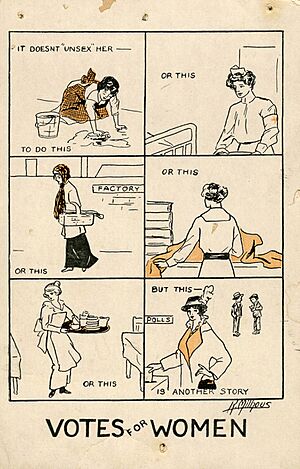

The New York Times, after first supporting voting rights, changed its mind and issued strong warnings. A 1912 editorial predicted that with voting rights, women would make impossible demands. These included "serving as soldiers and sailors, police officers or firefighters...and would serve on juries and elect themselves to executive offices and judgeships." It blamed a lack of masculinity for men not fighting back. It warned women would get the vote "if the men are not firm and wise enough and, it may as well be said, masculine enough to prevent them."

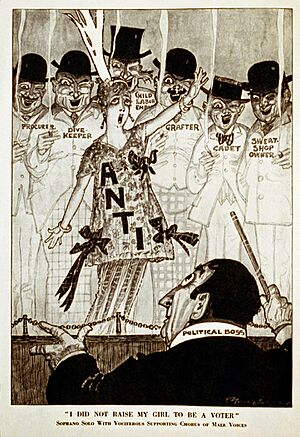

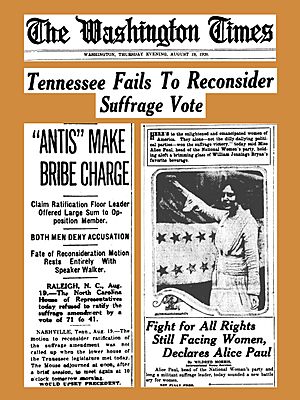

Women Against Voting Rights

Anti-suffrage groups, first called "remonstrants," organized as early as 1870. That's when the Woman's Anti-Suffrage Association of Washington was formed. Known as the "antis," they eventually created groups in about twenty states. In 1911, the National Association Opposed to Women's Suffrage was created. It claimed 350,000 members and opposed women's voting rights, feminism, and socialism. It argued that women voting "would reduce the special protections and ways women could influence things, destroy the family, and increase the number of socialist-leaning voters."

Middle and upper-class anti-suffrage women were conservatives with several reasons. Society women, in particular, had direct access to powerful politicians. They were hesitant to give up that advantage. Most often, the antis believed that politics was dirty. They thought women's involvement would make women lose the moral high ground they had claimed. They also thought that political disagreements would disrupt local club work for community improvement, as seen in the General Federation of Women's Clubs. The best-organized movement was the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NYSAOWS). Its belief, set down by its president Josephine Jewell Dodge, was:

We believe in every possible advancement for women. We believe that this advancement should be along those proper lines of work and effort for which she is best suited and for which she now has endless opportunities. We believe this advancement will be better achieved through strictly non-partisan effort and without the limits of the ballot. We believe in Progress, not in Politics for women.

The New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NYSAOWS) used grassroots organizing methods they learned from watching the suffragists. They used these to defeat the 1915 vote. They were very similar to the suffragists themselves. But they used a counter-campaign style, warning of the bad things that voting rights would bring to women. They rejected leadership by men. They stressed the importance of independent women in charity and social improvement. NYSAOWS was narrowly defeated in New York in 1916. The state voted to give women the vote. The organization moved to Washington to oppose the federal constitutional amendment for voting rights. It became the "National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage" (NAOWS). There, men took it over. It adopted a much harsher tone, especially attacking "red radicalism." After 1919, the antis easily adjusted to women having the right to vote. They became active in party affairs, especially in the Republican Party.

Southern Strategy for Voting Rights

The Constitution required 34 states (three-fourths of the 45 states in 1900) to approve an amendment. Unless the rest of the country was unanimous, there had to be support from at least some of the 11 former Confederate states for the Amendment to succeed. The South was the most traditional region and always gave the least support for voting rights. There was little or no voting rights activity in the region until the late 1800s. Historians point out four distinct Southern characteristics that made the South hesitant. First, Southern white men held traditional views about women's public roles. Second, the Solid South was tightly controlled by the Democratic Party, so playing the two parties against each other was not a possible strategy. Third, strong support for states' rights meant there was automatic opposition to a federal constitutional amendment. Fourth, Jim Crow attitudes meant that giving the vote to women, which would have included black women, was strongly opposed. Three more Western territories became states by 1912, helping the pro-Amendment numbers. Now, 36 states out of 48 were needed. In the end, Tennessee was the critical 36th state to approve it on August 18, 1920.

Mildred Rutherford, president of the Georgia United Daughters of the Confederacy and a leader of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, clearly stated the opposition of elite white women to voting rights in a 1914 speech to the Georgia state legislature:

The women who are working for this measure are attacking the principle for which their fathers fought during the Civil War. Woman's suffrage comes from the North and the West and from women who do not believe in state's rights and who wish to see black women using the ballot. I do not believe the state of Georgia has fallen so low that her good men cannot make laws for women. If this time ever comes then it will be time for women to claim the ballot.

Elna Green notes that, "Voting rights supporters claimed that women with the vote would outlaw child labor, pass minimum-wage and maximum-hours laws for women workers, and create health and safety standards for factory workers." The threat of these reforms united plantation owners, textile mill owners, railroad leaders, city political bosses, and the liquor industry in a strong group against voting rights.

Henry Browne Blackwell, an officer of the AWSA before the merger and an important figure in the movement afterward, urged the voting rights movement to try a strategy. He wanted them to convince Southern political leaders that they could keep white supremacy in their region without breaking the Fifteenth Amendment. This could be done by giving voting rights to educated women, who would mostly be white. Soon after Blackwell presented his idea to the Mississippi delegation in Congress, his plan was seriously considered by the Mississippi Constitutional Convention of 1890. Its main goal was to find legal ways to further limit the political power of African Americans. Although the convention adopted other measures instead, the fact that Blackwell's ideas were taken seriously interested many voting rights supporters.

Blackwell's ally in this effort was Laura Clay. She convinced the NAWSA to start a state-by-state campaign in the South based on Blackwell's strategy. Clay was one of several Southern NAWSA members who opposed a national women's voting rights amendment. They believed it would interfere with states' rights. (A generation later, Clay campaigned against the national amendment during the final fight for its approval.) With some supporters of this strategy predicting that the South would lead the way in giving women the right to vote, voting rights groups were started throughout the region. Anthony, Catt, and Blackwell campaigned for voting rights in the South in 1895. The latter two called for voting rights only for educated women. With Anthony's reluctant help, the NAWSA tried to fit in with the politics of white supremacy in that region. Anthony asked her old friend Frederick Douglass, a former slave, not to attend the NAWSA convention in Atlanta in 1895. This was the first convention held in a Southern city. Black NAWSA members were excluded from the 1903 convention in New Orleans, a Southern city. This marked the peak of this strategy's influence.

The leaders of the Southern movement were privileged upper-class women. They had a strong position in high society and church affairs. They tried to use their high-class connections to convince powerful men that voting rights were a good idea to make society better. They also argued that giving white women the vote would more than balance out giving the vote to the smaller number of black women. However, no Southern state gave women the right to vote because of this strategy. Most Southern voting rights societies that were started during this time became inactive. The NAWSA leadership later said it would not adopt policies that "supported excluding any race or class from the right to vote." Still, NAWSA showed its white members' views by downplaying the role of black suffragists.

Fighting Against Racism in the Movement

The women's voting rights movement, led in the 1800s by strong women like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, started from the abolitionist movement (which fought to end slavery). But by the early 1900s, Anthony's goal of voting rights for everyone was overshadowed by widespread racism in the United States. Earlier suffragists had believed the two issues could be linked. But the passing of the Fourteenth Amendment and Fifteenth Amendment forced a separation between African-American rights and women's voting rights. This was because it prioritized voting rights for black men over voting rights for all men and women. In 1903, the NAWSA officially adopted a platform of states' rights. This was meant to calm and bring Southern U.S. voting rights groups into the organization. The statement's signers included Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt, and Anna Howard Shaw.

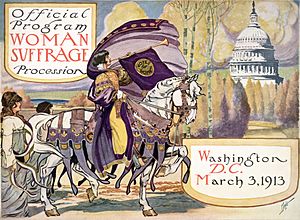

Because "racial" segregation was common throughout the country and within groups like the NAWSA, black people formed their own activist groups to fight for their equal rights. Many were college-educated and disliked being excluded from political power. The fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation (which freed slaves) in 1863 also fell in 1913. This gave them even more reason to march in the voting rights parade. Nellie Quander of Alpha Kappa Alpha—the nation's oldest black sorority—asked for a place in the college women's section for the women of Howard University. There were letters discussing this. One letter from February 17, 1913, talks about the desire for the Howard women to have a good place in the march. It also mentions letters and requests from an AKA sorority member, the leader of the suffrage parade, the vice president of the NAWSA, and the person who appointed Paul and Burns as parade organizers, Jane Addams. These letters were follow-up talks to the one started by Paul and initiated by Elise Hill. Hill went to Howard University at Paul's request to recruit the Howard women. The Howard University group included an artist, six college women (like Mary Church Terrell), a teacher, a musician, two professional women, Ida B. Wells-Barnett from the Illinois group, Mrs. McCoy from Michigan (who carried the banner), a group of twenty-five girls from Howard University in caps and gowns, and homemakers. One trained nurse marched, and an old "mammy" was brought by the Delaware group.

But Virginia-born Gardener tried to convince Paul that including black people would be a bad idea. This was because the Southern groups were threatening to leave the march. Paul had tried to keep news about black marchers out of the press. But when the Howard group announced they planned to participate, the public learned about the conflict. A newspaper said that Paul told some black suffragists that the NAWSA believed in equal rights for "colored women." But she also said that some Southern women would likely object to their presence. A source in the organization insisted that the official stance was to "allow black people to march if they wanted to." In a 1974 interview, Paul remembered the "hurdle" of Terrell's plan to march, which upset the Southern groups. She said the problem was solved when a Quaker leading the men's section suggested the men march between the Southern groups and the Howard University group.

In Paul's memory, a compromise was reached to order the parade with Southern women, then the men's section, and finally the black women's section. However, reports in the NAACP paper, The Crisis, show events happening quite differently. Black women protested the plan to segregate them. What is clear is that some groups tried, on the day of the parade, to separate their groups. For example, a last-minute instruction by the head of the state group section, Genevieve Stone, caused more uproar. She asked the Illinois group's only black member, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, to march with the segregated black group at the back of the parade. Some historians claim Paul made the request, though this seems unlikely after the official NAWSA decision. Wells-Barnett eventually rejoined the Illinois group as the parade moved down the avenue. In the end, black women marched in several state groups, including New York and Michigan. Some joined their co-workers in the professional groups. There were also black men driving many of the floats. The spectators did not treat the black participants any differently.

The "New Woman" and Public Action

The idea of the New Woman appeared in the late 1800s. It described the increasingly independent actions of women, especially the younger generation.

Women's move into public spaces was shown in many ways. In the late 1890s, riding bicycles became popular. This increased women's freedom to move around. It also showed a rejection of old ideas about women being weak and fragile. Susan B. Anthony said bicycles had "done more to free women than anything else in the world." Elizabeth Cady Stanton said that "Woman is riding to suffrage on the bicycle."

Activists campaigned for voting rights in ways that many still considered "unladylike." These included marching in parades and giving speeches on street corners. In New York in 1912, suffragists organized a twelve-day, 170-mile "Hike to Albany." They wanted to deliver voting rights petitions to the new governor. In 1913, the suffragist "Army of the Hudson" marched 250 miles from New York to Washington in sixteen days, getting national attention.

New Voting Rights Organizations

College Equal Suffrage League

When Maud Wood Park attended the NAWSA convention in 1900, she felt like she was almost the only young person there. After returning to Boston, she formed the College Equal Suffrage League with help from fellow Radcliffe graduate Inez Haynes Irwin. This group joined with the NAWSA. Mostly through Park's efforts, similar groups were started on college campuses in 30 states. This led to the formation of the National College Equal Suffrage League in 1908.

Equality League of Self-Supporting Women

The dramatic methods of the strong British voting rights movement started to influence the movement in the U.S. Harriet Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, returned to the U.S. after several years in England. There, she had been involved with voting rights groups that were becoming more active. In 1907, she founded the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women, later called the Women's Political Union. Its members were working women, both professionals and factory workers. The Equality League started the practice of holding voting rights parades and organized the first open-air voting rights rallies in thirty years. As many as 25,000 people marched in these parades.

National Council of Women Voters

The National Council of Women Voters (NCWV) was founded in 1911. Its purpose was to represent women in states where women had already gained the right to vote. Initially, these states were Wyoming, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Washington. Some other states, including California, followed soon after. Emma Smith Devoe served as the NCWV's president for all nine years of its existence. She had been president of the Washington Equal Suffrage Association during the successful voting rights campaign in that state in 1910. The NCWV acted as a political pressure group. It worked for laws important to women in the states where women could vote. As more states gained voting rights, the NCWV was increasingly able to use its political power to help pass the Nineteenth Amendment. After the Nineteenth Amendment passed, the NCWV and the NAWSA combined to form the League of Women Voters.

National Woman's Party

Work for a national voting rights amendment had greatly decreased after the two rival voting rights groups merged in 1890 to form the NAWSA. Interest in a national voting rights amendment was revived mainly by Alice Paul. In 1910, she returned to the U.S. from England. There, she had been part of the strong wing of the voting rights movement. Paul had been jailed there and had been force-fed after going on a hunger strike. In January 1913, she arrived in Washington as chair of the Congressional Committee of the NAWSA. Her job was to restart the push for a constitutional amendment that would give women the right to vote. She and her co-worker Lucy Burns organized a voting rights parade in Washington the day before Woodrow Wilson became president. Opponents of the march turned the event into a near riot. It only ended when an army cavalry unit was brought in to restore order. Public anger over the incident, which cost the police chief his job, brought attention to the movement and gave it new energy. In 1914, Paul and her followers started calling the proposed voting rights amendment the "Susan B. Anthony Amendment," a name that became widely used.

Paul argued that since the Democrats would not act to give women the right to vote (even though they controlled the presidency and both houses of Congress), the voting rights movement should work to defeat all Democratic candidates, no matter what an individual candidate's position on voting rights was. She and Burns formed a separate lobbying group called the Congressional Union to act on this approach. Strongly disagreeing, the NAWSA in 1913 stopped supporting Paul's group. It continued its practice of supporting any candidate who supported voting rights, regardless of political party. In 1916, Blatch merged her Women's Political Union into Paul's Congressional Union.

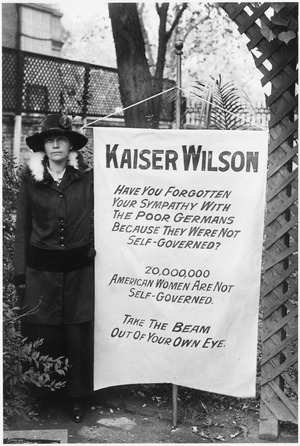

In 1916, Paul formed the National Woman's Party (NWP). Once again, the women's movement had split. But this time, it was like a division of labor. The NAWSA improved its image of being respectable. It engaged in very organized lobbying at both national and state levels. The smaller NWP also lobbied. But it became increasingly known for dramatic and confrontational activities, most often in the nation's capital. One type of protest was the watchfires. This involved burning copies of President Wilson's speeches, often outside the White House or in the nearby Lafayette Park. The NWP continued to hold watchfires even as the war began. This drew criticism from the public and even other voting rights groups for being unpatriotic.

Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference

The leaders of the NAWSA's Southern Strategy started to find their own voice by 1913. Kate Gordon of Louisiana and Laura Clay of Kentucky formed the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference (SSWSC). The suffragists of the SSWSC chose to work within the Jim Crow customs of their states. They spoke openly about how giving white women the right to vote would improve the social, economic, and political work related to white supremacy. To make it clear how their political ideas fit within the increasingly strict rules of segregation, they published a newspaper, New Southern Citizen, with the motto: "Make the Southern States White." The SSWSC became more and more at odds with NAWSA and its main focus on achieving a federal amendment. Most southern suffragists, however, disagreed and continued to work with the NAWSA. Gordon actively campaigned against the Nineteenth Amendment because, in theory, it would also give African-American women the right to vote. This would, as Laura Clay stated in a debate with Kentucky Equal Rights Association president Madeline McDowell Breckinridge, bring back the idea of Reconstruction Era interventions and lead to more federal scrutiny of elections in the South.

Voting Rights Newspapers

Stanton and Anthony started a sixteen-page weekly newspaper called The Revolution in 1868. It focused mainly on women's rights, especially voting rights. But it also covered politics, the labor movement, and other topics. Its energetic and wide-ranging style gave it a lasting influence. However, its debts grew when it did not receive the money they had expected. They had to give the paper to others after only twenty-nine months. Their organization, the NWSA, then relied on other newspapers, like The National Citizen and Ballot Box, edited by Matilda Joslyn Gage, and The Woman's Tribune, edited by Clara Bewick Colby, to share its views.

In 1870, soon after the AWSA was formed, Lucy Stone started an eight-page weekly newspaper called the Woman's Journal. It supported women's rights, especially voting rights. It had more money and was less radical than The Revolution. It lasted much longer. By the 1880s, it had become an unofficial voice for the entire voting rights movement. In 1916, the NAWSA bought the Woman's Journal and spent a lot of money to improve it. It was renamed Woman Citizen and declared the official newspaper of the NAWSA.

Alice Paul began publishing a newspaper called The Suffragist in 1913 when she was still part of the NAWSA. The editor of the eight-page weekly was Rheta Childe Dorr, an experienced journalist.

The Tide Turns for Women's Voting Rights

New Zealand gave women the right to vote in 1893. It was the first country to do so nationwide. In the U.S., women gained the right to vote in Washington in 1910; in California in 1911; in Oregon, Kansas, and Arizona in 1912; and in Illinois in 1913. Some states allowed women to vote in school elections, city elections, or for members of the Electoral College. Some territories, like Washington, Utah, and Wyoming, allowed women to vote before they became states. As women voted in more and more states, Congressmen from those states began to support a national voting rights amendment. They also paid more attention to issues like child labor.

The reform campaigns of the Progressive Era strengthened the voting rights movement. Starting around 1900, this broad movement began at the local level. Its goals included fighting government corruption, ending child labor, and protecting workers and consumers. Many people involved saw women's voting rights as another progressive goal. They believed that adding women to the voters would help their movement achieve its other goals. In 1912, the Progressive Party, formed by Theodore Roosevelt, supported women's voting rights. The socialist movement also supported women's voting rights in some areas.

By 1916, voting rights for women had become a major national issue. The NAWSA had become the nation's largest volunteer organization, with two million members. In 1916, both the Democratic and Republican parties' conventions supported women's voting rights. But they only supported it on a state-by-state basis. This meant that different states might give voting rights in different ways, or not at all. Expecting more, Catt called an emergency NAWSA convention. She proposed what became known as the "Winning Plan." For several years, the NAWSA had focused on getting voting rights state by state. This was partly to accommodate members from Southern states who opposed a national voting rights amendment, seeing it as interfering with states' rights. In a strategic change, the 1916 convention approved Catt's proposal to make a national amendment the top priority for the entire organization. It allowed the executive board to create a work plan for this goal for each state. It also allowed the board to take over that work if the state organization refused to follow.

In 1917, Catt received $900,000 from Mrs. Frank (Miriam) Leslie to be used for the women's voting rights movement. Catt formed the Leslie Woman Suffrage Commission to distribute the funds. Most of this money supported the NAWSA's activities at a crucial time for the voting rights movement.

In January 1917, the NWP placed pickets (protesters) at the White House. This had never been done before. They held banners demanding women's voting rights. Tension grew in June when a Russian group drove up to the White House. NWP members unrolled a banner that read, "We, the women of America, tell you that America is not a democracy. Twenty million American women are denied the right to vote. President Wilson is the chief opponent of their national voting rights." In August, another banner called President Wilson "Kaiser Wilson" and compared the situation of American women to that of the German people.

Some onlookers, including crowds of men who had been drinking and were in town for President Wilson's second inauguration, reacted violently. They tore the banners from the protesters' hands. The police, who had been calm before, started arresting the protesters for blocking the sidewalk. Eventually, over 200 were arrested. About half of them were sent to prison. In October, Alice Paul was sentenced to seven months in prison. When she and other suffragist prisoners started a hunger strike, prison authorities force-fed them. The bad publicity from this harsh practice increased pressure on the government. The administration gave in and released all the prisoners.

The U.S. joining World War I in April 1917 had a big impact on the voting rights movement. To replace men who had gone into the military, women moved into jobs that traditionally did not hire women, like steel mills and oil refineries. The NAWSA cooperated with the war effort. Catt and Shaw served on the Women's Committee for the Council of National Defense. The NWP, however, did not cooperate with the war effort. Jeannette Rankin, elected in 1916 by Montana as the first woman in Congress, was one of fifty members of Congress to vote against declaring war.

In November 1917, a public vote to give women the right to vote in New York—at that time the most populated state—passed by a large amount. In September 1918, President Wilson spoke before the Senate. He called for approval of the voting rights amendment as a war measure. He said, "We have made partners of the women in this war; shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?" In the 1918 elections, despite the threat of Spanish flu, three more states (Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Michigan) passed public votes to give women the right to vote. Two sitting senators (John W. Weeks of Massachusetts and Willard Saulsbury Jr. of Delaware) lost their re-election campaigns because they opposed voting rights. By the end of 1919, women could effectively vote for president in states with 326 electoral votes out of a total of 531. Political leaders who became convinced that women's voting rights were unavoidable began to pressure local and national lawmakers to support it. This was so their party could take credit for it in future elections.

The war helped speed up the extension of voting rights in several countries. Women gained the vote after years of campaigning, partly in recognition of their support for the war effort. This further increased the pressure for voting rights in the U.S. About half of the women in Britain had gained voting rights by January 1918, as had women in most Canadian provinces, with Quebec being the main exception.

The Nineteenth Amendment Passes

World War I had a big impact on women's voting rights in countries involved in the war. Women played a major role on the home fronts. Many countries recognized their sacrifices by giving them the vote during or soon after the war. These included the U.S., Britain, Canada (except Quebec), Denmark, Austria, the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and Sweden. Ireland also introduced universal voting rights with independence. France almost did so but stopped short. Despite their eventual success, groups like the National Woman's Party that continued strong protests during wartime were criticized by other voting rights groups and the public. They were seen as unpatriotic.

On January 12, 1915, a voting rights bill was brought before the House of Representatives. But it was defeated by a vote of 204 to 174. President Woodrow Wilson waited until he was sure the Democratic Party supported it. The 1917 vote in New York State in favor of voting rights was key for him. When another bill was brought before the House in January 1918, Wilson made a strong and widely published appeal to the House to pass the bill. One historian argues that: The National American Woman Suffrage Association, not the National Woman's Party, was crucial in Wilson changing his mind about the federal amendment. This was because its approach matched his own careful way of making reforms: get wide agreement, create a good reason, and make the issue politically valuable. Also, I believe Wilson played a significant role in the successful passing of the 19th Amendment in Congress and its national approval.

The Amendment passed by two-thirds of the House, with only one vote to spare. The vote then went to the Senate. Again, President Wilson made an appeal. But on September 30, 1918, the amendment fell two votes short of the two-thirds needed to pass. On February 10, 1919, it was voted on again, and then it lost by only one vote.

There was much worry among politicians of both parties to get the amendment passed and working before the general elections of 1920. So, the President called a special session of Congress. A bill, introducing the amendment, was brought before the House again. On May 21, 1919, it passed, 304 to 89, with 42 more votes than needed. On June 4, 1919, it was brought before the Senate. After a long discussion, it passed, with 56 votes for and 25 against. Within a few days, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Michigan approved the amendment, as their legislatures were in session. Other states followed at a steady pace, until 35 of the necessary 36 state legislatures had approved the amendment. After Washington on March 22, 1920, approval slowed for months. Finally, on August 18, 1920, Tennessee narrowly approved the Nineteenth Amendment. This made it the law throughout the United States. So, the 1920 election became the first United States presidential election in which women were allowed to vote in every state.

Three other states, Connecticut, Vermont, and Delaware, passed the amendment by 1923. They were eventually followed by others in the South. Nearly twenty years later, Maryland approved the amendment in 1941. After another ten years, in 1952, Virginia approved the Nineteenth Amendment, followed by Alabama in 1953. After another 16 years, Florida and South Carolina passed the necessary votes to approve it in 1969. They were followed two years later by Georgia, Louisiana, and North Carolina.

Mississippi did not approve the Nineteenth Amendment until 1984, sixty-four years after the law was made national.

What Changed After the Nineteenth Amendment?

Changes in the United States

Politicians responded to the newly larger group of voters by focusing on issues important to women. These included prohibition, child health, public schools, and world peace. Women did care about these issues. But in general voting, they had the same views and voting behavior as men.

The voting rights organization NAWSA became the League of Women Voters. Alice Paul's National Woman's Party started pushing for full equality and the Equal Rights Amendment. This amendment would pass Congress during the second wave of the women's movement in 1972 (but it was not approved by enough states and never became law). The main surge of women voting came in 1928. This was when big-city political groups realized they needed women's support to elect Al Smith. Meanwhile, rural groups who supported prohibition encouraged women to support prohibition and vote for Republican Herbert Hoover. Catholic women were hesitant to vote in the early 1920s. But they registered in very large numbers for the 1928 election—the first election where Catholicism was a major issue. A few women were elected to office. But none became especially famous during this time. Overall, the women's rights movement slowed down noticeably during the 1920s.

Even though the Nineteenth Amendment made it unconstitutional to restrict voting based on sex in 1920, women did not vote in the same numbers as men until 1980. A term often used for the push for equal representation in government is Mirror Representation. This means the number of men and women in government should match their proportion in the population. From 1980 until now, women have voted in elections at least as much as men, and often more. This difference in voting turnout and preferences between men and women is called the voting gender gap. The voting gender gap has affected political elections and, as a result, how candidates campaign for office.

The Nineteenth Amendment did not actually give voting rights to all women in the United States. Women's rights to a public identity were limited by the old law of coverture. Since women were not citizens in their own right, and married women had to take on the citizenship and residency of their husbands, many women lost voting rights upon marriage. The Naturalization Act of 1790 gave any free white person who met certain character and residency rules the right to become a citizen. The 14th Amendment extended citizenship to those born in the United States, including African Americans. Supreme Court rulings allowed racial limits on naturalization for people who were neither black nor white. This meant that Latinos, Asians, and Eastern Europeans, among other groups, were at various times stopped from becoming citizens. Limits based on race also applied to Native American women living on reservations until the Indian Citizenship Act passed in 1924. As a result, if an American woman married someone who could not become a citizen, she lost her citizenship until the Cable Act of 1922 and other changes were passed.

Since the U.S. Constitution allows states to decide who can vote in elections, until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed, different laws among the states led to very different civil rights for women depending on where they lived. Restrictions on literacy (being able to read and write), moral character, and the ability to pay poll taxes were used to legally stop women from voting. Large numbers of African American women, as well as men, continued to be denied voting rights in the Southern states. Latinos and women who did not speak English were regularly excluded by literacy requirements in the Northern states. Many poor women, regardless of race, could not pay poll taxes. Since married women's wages and legal access to money were controlled by their husbands, many married women could not pay poll taxes. In 1940, U.S. women were granted their own legal status as citizens. Rules were made for women who had previously lost their citizenship through marriage to get it back.

Native American Women's Voting Rights

The early women's voting rights movement was inspired by the political equality in Iroquois society. Native American women and men were officially given the right to vote in 1924 when the Indian Citizenship Act passed. Even so, until the 1950s, some states stopped Native Americans from voting unless they had adopted American culture and language, given up their tribal memberships, or moved to cities. Universal voting rights were not truly guaranteed until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed. Voters in Indian country still face some barriers to political participation.

Voting Rights in U.S. Territories

When the 19th Amendment passed, both Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands were U.S. territories. Voting rights supporters believed that women in the Virgin Islands had gained the right to vote when the Danish extended suffrage in 1915, as the Danish West Indies were their possession then. Similarly, since Puerto Ricans were confirmed as U.S. citizens in 1917, it was assumed that voting rights had been extended there too with the 19th Amendment. However, when Governor Arthur Yager questioned its use in Puerto Rico, he received clarification from the Bureau of Insular Affairs. They said that passing or approving the amendment in the states would not give women voting rights in Puerto Rico. This was because of the island's status as an unincorporated territory. In 1921, the U.S. Supreme Court clarified that constitutional rights did not extend to residents in the two territories. This was because their rights were defined in Puerto Rico by the Organic Act of 1900 and in the Virgin Islands by the Danish Colonial Law of 1906.