Jeannette Rankin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jeannette Rankin

|

|

|---|---|

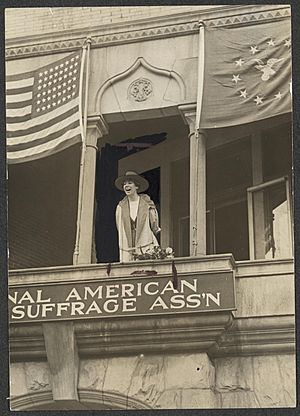

Rankin in 1917

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Montana |

|

| In office January 3, 1941 – January 3, 1943 |

|

| Preceded by | Jacob Thorkelson |

| Succeeded by | Mike Mansfield |

| Constituency | 1st district |

| In office March 4, 1917 – March 3, 1919 Serving with John Evans

|

|

| Preceded by | Tom Stout |

| Succeeded by |

|

| Constituency | At-large district |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Jeannette Pickering Rankin

June 11, 1880 Missoula County, Montana, U.S. |

| Died | May 18, 1973 (aged 92) Carmel, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Education |

|

Jeannette Pickering Rankin (June 11, 1880 – May 18, 1973) was an amazing American politician and a champion for women's rights. In 1917, she made history by becoming the first woman ever to hold a federal office in the United States. A federal office means she was elected to a national position, like being a member of Congress.

She was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Montana in 1916 as a Republican. She served one term, then was elected again in 1940. Even today, Jeannette Rankin is the only woman ever elected to Congress from Montana.

It's interesting that both times Rankin was in Congress, the U.S. was about to enter a world war. She was a pacifist her whole life, which means she believed in solving problems without war. In 1917, she was one of only 50 House members who voted against declaring war on Germany. In 1941, she was the only member of Congress to vote against declaring war on Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

During the Progressive Era, Rankin was a suffragist. This means she worked hard to get women the right to vote. She helped organize and push for laws that allowed women to vote in several states, including Montana and New York. While in Congress, she helped create the law that became the 19th Amendment. This important amendment gave all women across the country the right to vote. She spent over sixty years fighting for women's rights and civil rights.

Contents

Early Life and Dreams

Jeannette Rankin was born on June 11, 1880, near Missoula in Montana Territory. This was nine years before Montana became a state. Her mother, Olive, was a school teacher, and her father, John, was a wealthy mill owner. Jeannette was the oldest of six children. Her brother, Wellington, later became Montana's attorney general. Her sister, Edna Rankin McKinnon, was the first woman born in Montana to become a lawyer.

Growing up on her family's ranch, Jeannette had many chores. She cleaned, sewed, did farm work, and helped care for her younger siblings. She even helped fix ranch machinery. Once, she built a wooden sidewalk by herself for a building her father owned. Jeannette noticed that women on the western frontier worked just as hard as men, but they didn't have the right to vote or an equal say in politics.

She finished high school in 1898 and then studied at the University of Montana. In 1902, she earned a degree in biology. Before becoming a politician, she tried different jobs like dressmaking, furniture design, and teaching. After her father passed away in 1904, Jeannette took on the responsibility of looking after her younger brothers and sisters.

Fighting for the Right to Vote

When she was 27, Jeannette moved to San Francisco to work in social work, which was a new field at the time. She felt this was her true calling. She then studied at the New York School of Philanthropy from 1908 to 1909. After working briefly in Spokane, Washington, she moved to Seattle. There, she attended the University of Washington and became very involved in the women's suffrage movement.

In November 1910, voters in Washington state approved a change to their constitution. This change gave women the permanent right to vote, making Washington the fifth state to do so. Rankin then went back to New York and helped organize the New York Woman Suffrage Party. This group worked with others to pass a similar voting rights bill in New York. During this time, Rankin also traveled to Washington, D.C., to speak to Congress for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Rankin returned to Montana and quickly became a leader in the suffrage movement. She became the president of the Montana Women's Suffrage Association. In February 1911, she was the first woman to speak to the Montana legislature. She argued strongly for women to get the right to vote in her home state. In November 1914, Montana became the seventh state to give women full voting rights. Rankin was great at bringing different grassroots organizations together to help her suffrage campaigns in New York and Montana. She later used these same methods for her 1916 campaign for Congress.

Rankin believed that getting women the right to vote was similar to her work for peace. She thought that if more women were involved in government, it would be less corrupt and work better. At a meeting about peace, she once said, "The peace problem is a woman's problem."

First Woman in Congress

Jeannette Rankin's campaign for one of Montana's two House seats in 1916 was supported by her brother Wellington. He was an important member of the Montana Republican Party. She traveled long distances across Montana to meet people. She spoke at train stations, street corners, potluck dinners on ranches, and in small, one-room schoolhouses. She ran as a progressive, focusing on her support for women's voting rights, social programs, and banning alcohol.

In the Republican primary, Rankin received the most votes. In the main election on November 7, the two candidates with the most votes won the seats. Rankin came in second, becoming the first woman elected to Congress! After her victory, she said she was "deeply conscious of the responsibility" she had as the only woman in Congress with voting power. Her election created a lot of excitement across the country.

Soon after she started her term, Congress had an emergency meeting. Germany had started attacking all ships in the Atlantic Ocean. On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. After a lot of discussion, the vote happened in the House at 3:00 AM on April 6. Rankin was one of only 50 people who voted against the war. She said, "I wish to stand for my country, but I cannot vote for war." Years later, she added, "I felt the first time the first woman had a chance to say no to war, she should say it." Even though many men also voted against the war, Rankin was criticized the most. Some people thought her vote hurt the women's suffrage movement, but others praised her.

Rankin also worked to improve conditions for workers. In 1917, a terrible mining accident in Butte, Montana, killed 168 miners. Workers went on strike because of the dangerous conditions. Rankin tried to help, but the mining companies refused to meet with her. She also worked to improve conditions at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, where federal workers had long hours. She listened to their complaints and hired a reporter to investigate. Because of her efforts, the work day there was limited to eight hours.

By 1917, women had some voting rights in about 40 states. Rankin continued to lead the movement for all women to have the right to vote. She helped create the Committee on Woman Suffrage and was one of its first members. In January 1918, this committee presented its report to Congress. Rankin began the debate on a Constitutional amendment to give women universal voting rights. The resolution passed in the House but failed in the Senate. The next year, after Rankin's term ended, the same resolution passed both parts of Congress. After three-fourths of the states approved it, it became the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

During Rankin's time in office, Montana changed its Congressional seats. Instead of two state-wide seats, they created two smaller districts. It was hard for Rankin to win reelection in the new western district, which mostly supported the other party. So, she decided to run for the Senate in 1918. She lost the Republican primary and finished third in the general election.

Life Between Terms

After leaving Congress, Rankin worked for groups like the National Consumers League and as a lobbyist for peace organizations. A lobbyist tries to convince lawmakers to pass certain laws. She pushed for a Constitutional amendment to ban child labor. She also supported the Sheppard–Towner Act, which was the first federal program specifically for women and children. This law passed in 1921.

In 1924, Rankin bought a small farm in Georgia. She lived a very simple life there, without electricity or indoor plumbing. She also kept a home in Montana. Rankin often gave speeches around the country for peace groups. In 1928, she started the Georgia Peace Society, which worked for peace until 1941, just before the U.S. entered World War II.

In 1937, Rankin disagreed with President Franklin Roosevelt's ideas to get involved in the war in Europe. She believed that both sides wanted to avoid another war and would find a peaceful solution. She spoke to many Congressional committees against preparing for war. When she realized her efforts weren't working, Rankin decided to run for the House of Representatives again.

Her Second Term and a Brave Vote

Rankin started her campaign for Congress in 1939 by visiting high schools in Montana. She spoke at 52 of the 56 high schools in her district. This helped her reconnect with the area after spending so much time in Georgia. Again, her brother Wellington helped her politically, even though their lives and political views were becoming different.

In the 1940 election, Rankin, who was 60 years old, won against the person currently in office, Jacob Thorkelson. She was then assigned to committees that dealt with public lands and island affairs. For months, members of Congress and the public had been discussing whether the U.S. should join World War II. But the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, united the country and stopped almost all arguments against war.

On December 8, Jeannette Rankin was the only member of Congress to vote against declaring war on Japan. People in the audience hissed when she cast her vote. Some of her colleagues asked her to change her vote to make it unanimous, or at least not vote at all, but she refused. She said, "As a woman I can't go to war, and I refuse to send anyone else."

After the vote, many reporters followed Rankin into a small room. She had to hide in a phone booth until the Capitol Police came to take her to her office. There, she received many angry messages. One message from her brother said, "Montana is 100 percent against you." A photo of Rankin in the phone booth, calling for help, appeared in newspapers everywhere the next day.

Three days later, Congress voted on declaring war against Germany and Italy. Rankin chose not to vote this time. Her political career was effectively over, and she did not run for reelection in 1942. Years later, when asked if she regretted her vote, Rankin said, "Never. If you're against war, you're against war regardless of what happens. It's a wrong method of trying to settle a dispute."

Later Years and Lasting Impact

For the next twenty years, Rankin traveled the world. She often visited India, where she learned about the peaceful teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. She kept homes in both Georgia and Montana.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a new generation of peace activists and feminists found inspiration in Rankin. She became active again because of the Vietnam War. In January 1968, a group of women's peace organizations called the Jeannette Rankin Brigade organized a large anti-war march in Washington, D.C. It was the biggest march by women since 1913. Rankin led 5,000 people from Union Station to the Capitol Building. There, they gave a peace petition to the House Speaker. In 1972, when she was in her nineties, Rankin thought about running for Congress a third time to speak out more against the Vietnam War. However, health problems stopped her from doing so.

Death and Legacy

Jeannette Rankin passed away on May 18, 1973, at the age of 92, in Carmel, California. There is a memorial stone for her in the Missoula Cemetery. She left her property to help "mature, unemployed women workers." Her Montana home, called the Rankin Ranch, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

The Jeannette Rankin Foundation (now the Jeannette Rankin Women's Scholarship Fund) is a non-profit organization. It gives annual educational scholarships to low-income women aged 35 and older across the United States. Starting with one $500 scholarship in 1978, the fund has now given over $1.8 million in scholarships to more than 700 women.

A statue of Rankin was placed in the United States Capitol's Statuary Hall in 1985. It has the words "I Cannot Vote For War" carved on it. A copy of the statue is also in Montana's capitol building in Helena. In 1993, Rankin was honored by being added to the National Women's Hall of Fame.

In 2004, a play called A Single Woman was created based on Rankin's life. It was performed to help peace organizations. There was also a film version of the play.

An Opera America commissioned a series of songs about Rankin called Fierce Grace, which first played in 2017. In 2018, a brewery in Montana had a mural painted on its building featuring Rankin and a quote from her.

Rankin is also the subject of a musical called We Won't Sleep.

Even though she is mostly remembered for her strong belief in peace, Rankin once said in 1972 that she wished to be remembered for something else. She stated, "If I am remembered for no other act, I want to be remembered as the only woman who ever voted to give women the right to vote."

See also

In Spanish: Jeannette Rankin para niños

In Spanish: Jeannette Rankin para niños

- History of the Republican Party (United States)

- List of peace activists

- Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

- Women in the United States House of Representatives

- Barbara Lee, the only member of Congress to vote against American military response to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks

- A Single Woman (2004 play)

- A Single Woman (2008 film)

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |