National American Woman Suffrage Association facts for kids

|

|

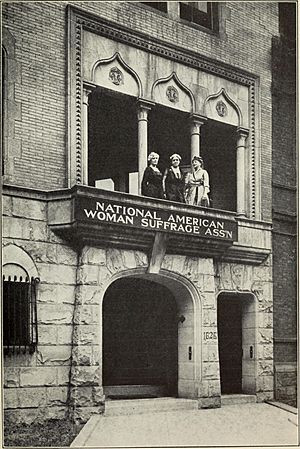

Gardener, Park and Catt at Suffrage House in Washington, D.C.

|

|

| Abbreviation | NAWSA |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | Merging of the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association |

| Successor | League of Women Voters |

| Formation | 1890 |

| Dissolved | 1920 |

|

Key people

|

Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Carrie Chapman Catt, Lucy Stone |

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was a very important group formed on February 18, 1890. Its main goal was to help women in the United States get the right to vote.

NAWSA was created when two older groups, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), joined together. When it started, it had about 7,000 members. Over time, it grew to have two million members, making it the largest volunteer organization in the country.

This powerful group played a huge part in getting the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution passed in 1920. This amendment finally gave women across the nation the right to vote.

Susan B. Anthony, a famous leader in the fight for women's vote, was a key figure in the new NAWSA. After she retired in 1900, Carrie Chapman Catt became president. Catt helped the group grow by inviting wealthy women from women's clubs to join. These women brought time, money, and experience to the movement.

Anna Howard Shaw took over as president in 1904. During her time, NAWSA's membership grew a lot, and more people started to support women's right to vote.

For a while, the movement focused on getting states to allow women to vote. But in 1910, Alice Paul joined NAWSA and helped bring attention back to changing the U.S. Constitution. Paul later started her own group, the National Woman's Party, because she had different ideas about how to achieve their goals.

When Carrie Chapman Catt became president again in 1915, NAWSA decided to focus mainly on getting the national amendment passed. The group became more like a political force, pushing for change. They also helped with the war effort during World War I, which gained them more support.

On February 14, 1920, before the Nineteenth Amendment was officially approved, NAWSA changed its name to the League of Women Voters. This group is still active today, helping people understand and participate in politics.

Contents

How the Movement Started

In the early days, not everyone agreed that women should have the right to vote. At the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, the first meeting for women's rights, the idea of women voting was debated a lot. But by the 1850s, getting the right to vote became a main goal for the women's movement.

Three important leaders from this time were Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony. They all played big roles in creating NAWSA many years later.

After the American Civil War in 1866, a group called the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed. It worked for equal rights, especially the right to vote, for both African Americans and white women.

However, the AERA broke apart in 1869. This happened partly because of disagreements over the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. This amendment would give African American men the right to vote, but not women. Stanton and Anthony did not want it passed unless women also got the right to vote. Lucy Stone supported the amendment, believing it would help women's suffrage later.

In May 1869, Anthony, Stanton, and their supporters formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In November 1869, Lucy Stone, her husband Henry Blackwell, and others formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). These two groups became rivals for many years.

Two Groups, Different Paths

Even after the Fifteenth Amendment was approved in 1870, the two groups had different ideas. The AWSA focused almost only on women's right to vote. The NWSA worked on many issues, like divorce reform and equal pay for women. The AWSA had both men and women as leaders, while the NWSA was led only by women.

The AWSA worked mostly at the state level, trying to get individual states to allow women to vote. The NWSA worked more at the national level, trying to change federal laws. The AWSA tried to seem very proper and respectable. The NWSA sometimes used more direct actions. For example, Susan B. Anthony was arrested in 1872 for voting, which was against the law for women at the time. Her trial was very public.

Progress for women's suffrage was slow after the groups split. But other changes helped the movement. By 1890, many women were going to college. The idea that women should only stay at home and not be involved in politics was fading. Laws that gave husbands full control over their wives were also changing.

Many women's groups, like the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), grew very large. The WCTU, which fought against alcohol, supported women's right to vote. They believed women needed the vote to protect their families.

Susan B. Anthony started to focus more on just getting the vote. She wanted to unite all women's groups for this one goal. The NWSA also started to act more respectable and less confrontational. This helped them become more like the AWSA.

In 1887, the U.S. Senate rejected a proposed amendment for women's suffrage. This made the NWSA put less effort into federal campaigns and more into state campaigns, just like the AWSA was already doing. This brought the two groups closer.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton still wanted to work on many women's rights issues. But she was less involved in the daily work of the suffrage movement. She and Anthony remained good friends and continued to work together.

Lucy Stone spent most of her time after the split working on the Woman's Journal. This weekly newspaper, started in 1870, was the voice of the AWSA. By the 1880s, it was seen as the newspaper for the whole movement.

Younger members of the suffrage movement were tired of the division between the two groups. Alice Stone Blackwell, Lucy Stone's daughter, said that the younger women on both sides wanted the groups to unite.

Joining Forces: The Merger

There had been many tries to bring the two groups together, but they never worked. This changed in 1887 when Lucy Stone, who was getting older and not well, started looking for ways to unite them.

In November 1887, the AWSA agreed to let Stone talk with Anthony about a merger. They felt that the differences between the groups were mostly gone. Stone sent this idea to Anthony and invited her to meet.

Anthony and Rachel Foster Avery, a young NWSA leader, met with Stone and her daughter Alice Stone Blackwell in Boston in December 1887. They talked about how the new group would be named and organized. Even though Stone had some doubts later, the merger process continued slowly.

A big sign of better relations came in 1888 at the first meeting of the International Council of Women. The NWSA organized this event. Representatives from the AWSA were invited to sit on the stage, showing a new spirit of cooperation.

The AWSA easily agreed to the merger. But in the NWSA, some members like Matilda Joslyn Gage and Olympia Brown strongly opposed it. Anthony's biographer, Ida Husted Harper, said the NWSA meetings about the merger were "the most stormy" in the group's history. Gage even started a new group, but it didn't last long.

In January 1889, committees from both groups signed an agreement to merge. In February, Stone, Stanton, Anthony, and other leaders announced their plan to work together.

The AWSA had been larger at first, but its strength had gone down in the 1880s. The NWSA was seen as the main suffrage group, partly because of Anthony's skill in getting attention. Anthony and Stanton had also written their huge History of Woman Suffrage, which put them at the center of the movement's story.

Anthony was becoming a very important political figure. In 1890, many important people, including members of Congress, attended her 70th birthday party. This event happened just before the convention that united the two groups. Anthony and Stanton showed their strong friendship at this party, which disappointed those who wanted to keep them apart.

The Founding Convention

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was officially created on February 18, 1890, in Washington, D.C. The convention delegates had to decide who would lead the new group. Lucy Stone was too sick to attend. Both Anthony and Stanton had supporters for president.

Before the convention, the AWSA and NWSA committees met separately. Henry Browne Blackwell, Lucy Stone's husband, told the AWSA that the NWSA had agreed to focus only on suffrage, not other issues. The AWSA recommended voting for Anthony. At the NWSA meeting, Anthony urged her members to vote for Stanton, saying that if Stanton lost, it would be seen as a rejection of her role.

When the votes were counted, Stanton became president with 131 votes. Anthony received 90 votes and was elected vice president. Stone was chosen as chair of the executive committee.

As president, Stanton gave the opening speech. She encouraged the new group to work on many reforms, not just suffrage. She even suggested controversial ideas, like women having leadership roles in religious groups. However, her ideas didn't have a lasting impact because most younger suffragists didn't agree with her broad approach.

Stanton and Anthony Lead NAWSA

Stanton's role as president was mostly symbolic. She soon left for England, leaving Anthony in charge. Stanton retired in 1892, and Anthony was then elected president, a role she had already been doing. Lucy Stone passed away in 1893 and did not play a big role in NAWSA.

The movement slowed down a bit right after the merger. The new group was small, with only about 7,000 members in 1893. It also had some organizational problems.

In 1893, NAWSA members May Wright Sewall and Rachel Foster Avery helped organize the World's Congress of Representative Women at the Chicago World's Fair.

In 1893, NAWSA decided to hold its yearly meetings in different cities, not just Washington, D.C. Anthony disagreed, fearing it would make the group focus less on a national amendment. She was right; NAWSA often didn't put money towards working with Congress.

The Woman's Bible

Stanton's radical ideas didn't fit well with the new organization. In 1895, she published The Woman's Bible. This book was very controversial because it criticized how the Bible was used to make women seem less important. Many within NAWSA felt the book would hurt their cause.

NAWSA voted to say they had no connection to the book. Anthony strongly objected, saying it was unnecessary and hurtful. The negative reaction to the book greatly reduced Stanton's influence in the suffrage movement. She passed away in 1902.

Southern Strategy

The Southern states had little interest in women's suffrage. In 1887, when the suffrage amendment was rejected by the Senate, no Southern senators voted for it. This was a problem because an amendment needed support from many states, including some in the South.

In 1867, Henry Blackwell suggested a plan: convince Southern leaders that giving educated women (who were mostly white) the right to vote would help keep white supremacy. Laura Clay helped convince NAWSA to try this strategy in the South. Many Southern NAWSA members, including Clay, opposed a national amendment because they felt it would interfere with states' rights.

In 1895, Susan B. Anthony asked her friend Frederick Douglass, a former slave, not to attend the NAWSA convention in Atlanta, the first in a Southern city. Black NAWSA members were also excluded from the 1903 convention in New Orleans. NAWSA stated that it respected "State's rights" and allowed each state group to manage its own affairs. As NAWSA pushed for a Constitutional Amendment, many Southern suffragists still opposed it because it would give Black women the right to vote. In 1914, Kate M. Gordon formed a group that opposed the Nineteenth Amendment for this reason.

Carrie Chapman Catt's First Term

Carrie Chapman Catt joined the suffrage movement in the 1880s. She was married to a wealthy engineer who supported her work, so she could dedicate a lot of time to the movement. She led several NAWSA committees. In 1895, she was in charge of NAWSA's Organization Committee and raised money to hire fourteen organizers. By 1899, there were suffrage groups in every state. When Anthony retired in 1900, she chose Catt to be the next president. Anthony remained influential until she passed away in 1906.

One of Catt's first actions was to start the "society plan." This plan aimed to get wealthy women from women's clubs to join the suffrage movement. These clubs were mostly made up of middle-class women who worked on community projects. They usually avoided controversial topics, but women's suffrage became more accepted among them. In 1914, the General Federation of Women's Clubs, a national group for women's clubs, officially supported women's suffrage.

To make the movement more appealing to middle and upper-class women, NAWSA started to tell a version of its history that played down earlier connections to controversial issues like racial equality or divorce reform. Stanton's role was often overlooked, as were the roles of Black women and working women. Anthony, who was once seen as a radical, was now honored as a "suffrage saint."

The energy of the Progressive Era also helped the suffrage movement. This movement, starting around 1900, aimed to fix problems in government and society, like child labor. Many people in this movement saw women's suffrage as another progressive goal that would help achieve other reforms.

Catt resigned after four years, partly because her husband was ill. She also wanted to help organize the International Woman Suffrage Alliance, which started in Berlin in 1904 with Catt as its president.

Anna Howard Shaw's Leadership

In 1904, Anna Howard Shaw, another person mentored by Anthony, became president of NAWSA. She served longer than anyone else. Shaw was a very energetic worker and a great speaker. While she wasn't as skilled at managing the organization as Catt, NAWSA grew a lot under her leadership.

In 1906, Southern NAWSA members formed the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference. This group had racist views and asked for NAWSA's support. Shaw refused, saying NAWSA would not support policies that excluded any race from voting.

In 1907, Harriet Stanton Blatch, Elizabeth Cady Stanton's daughter, started a competing group called the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women. This group, later known as the Women's Political Union, focused on working women. Blatch had seen more active suffrage groups in England. Her group gained followers by doing things NAWSA members thought were too bold, like suffrage parades and outdoor rallies.

In 1908, the National College Equal Suffrage League became part of NAWSA. It was started by Maud Wood Park, who later helped create similar groups in 30 states and became a key NAWSA leader.

By 1908, Catt was very active again. She and her team created a detailed plan to unite suffrage groups in New York City. In 1909, they founded the Woman Suffrage Party (WSP), which had 20,000 members by 1910.

Public opinion about the suffrage movement improved greatly during this time. Working for suffrage became a respected activity for middle-class women. By 1910, NAWSA had 117,000 members. That year, NAWSA opened its first permanent headquarters in New York City.

The change in public opinion also led to more success in state-level campaigns. In 1896, only four Western states allowed women to vote. From 1896 to 1910, six state campaigns failed. But in 1910, women won the right to vote in Washington state, followed by California in 1911, and Oregon, Kansas, and Arizona in 1912.

In 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois, president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), spoke out about NAWSA's hesitation to accept Black women. NAWSA responded politely, inviting him to speak at their next convention. However, NAWSA continued to downplay the role of Black suffragists. This was partly because racist attitudes were common at the time, and partly because NAWSA believed it needed support from Southern states, which practiced racial segregation, to pass a national amendment.

NAWSA's plan was to win suffrage state by state until enough women could vote to push for a national amendment. In 1913, the Southern States Woman Suffrage Committee was formed to stop this. Led by Kate Gordon, this group supported women's suffrage but opposed a federal amendment, saying it would violate states' rights. Gordon argued that a federal amendment for women's voting rights could lead to federal enforcement of voting rights for African Americans in the South, which she opposed. Her group was small, but her strong racist statements caused more divisions within NAWSA.

Despite NAWSA's growth, some members were unhappy with Shaw's leadership. She often reacted strongly to those who disagreed with her, causing problems within the organization. In 1915, she announced she would not run for reelection.

NAWSA Moves to Warren, Ohio

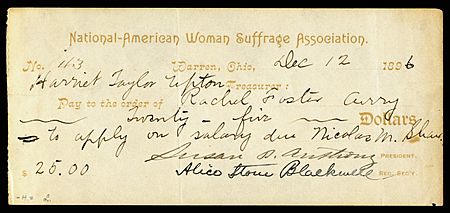

For several years, Harriet Taylor Upton led the women's suffrage movement in Trumbull County, Ohio. Her father was a U.S. Congressman, which allowed her to meet Susan B. Anthony. Anthony brought Upton into the suffrage movement.

In 1894, Upton became NAWSA's treasurer. She also led the Ohio state suffrage group from 1899-1908 and 1911–1920. Upton helped move NAWSA's national headquarters to her home in Warren, Ohio, in 1903. This was meant to be a temporary move but lasted six years. Susan B. Anthony visited Warren many times.

During this time, Warren became a focus for women's rights in the nation. The association's offices were in the Trumbull Court House. Even after the headquarters left Upton House around 1910, Warren remained active in the suffrage movement until the 19th Amendment was approved in 1920. In 1993, the Upton House became a historic landmark.

A Split in the Movement

A new challenge for NAWSA leaders began when Alice Paul returned to the U.S. in 1910 from England. In England, she had been part of a more aggressive suffrage movement. She had been jailed and treated harshly in prison, including being fed against her will, after going on a hunger strike.

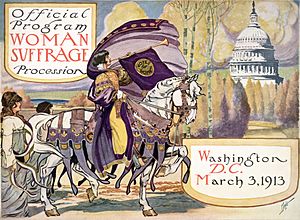

Paul joined NAWSA and helped bring new interest to the idea of a national amendment, which had been less of a focus for years. In 1912, Alice Paul was put in charge of NAWSA's Congressional Committee to restart the push for a federal amendment. In 1913, she and Lucy Burns organized the Woman Suffrage Procession, a large suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., the day before Woodrow Wilson became president. People who opposed the march caused a near riot, which ended only when the army stepped in. Public anger over this event brought a lot of attention to the movement.

Paul disagreed with NAWSA's leaders. She believed that since the Democratic Party controlled the presidency and Congress but wasn't acting to give women the vote, the suffrage movement should work to defeat all Democrats, no matter their individual stance on suffrage. NAWSA's policy was to support any candidate who supported suffrage, regardless of their party.

In 1913, Paul and Burns formed the Congressional Union (CU) to focus only on a national amendment. They sent organizers to states where NAWSA already had groups. The relationship between the CU and NAWSA became difficult.

At the NAWSA convention in 1913, Paul and her supporters demanded that the group focus only on a federal amendment. Instead, the convention limited the CU's power. After talks failed, NAWSA removed Paul from her leadership role. By February 1914, NAWSA and the CU had become two separate groups.

Blatch's Women's Political Union joined the CU. This group later became the National Woman's Party (NWP), which Paul formed in 1916. So, there were again two main national women's suffrage groups. NAWSA focused on being respectable and organized lobbying. The smaller NWP also lobbied but became known for more dramatic and confrontational actions, especially in Washington, D.C.

Carrie Chapman Catt's Second Term (1915-1920)

Carrie Chapman Catt, NAWSA's former president, was the clear choice to replace Anna Howard Shaw. Catt was leading a crucial suffrage campaign in New York State at the time. Many in NAWSA believed that winning in a large Eastern state would be a turning point for the national campaign. New York was the biggest state, and victory there seemed possible.

Catt agreed to take over the NAWSA presidency in December 1915, but only if she could choose her own executive board. She appointed wealthy women who could work full-time for the movement.

With more commitment and unity, Catt sent officers to assess the organization and make it more centralized and efficient. Catt said NAWSA was like "a camel with a hundred humps, each with a blind driver." She provided clear direction with many messages to state and local groups, giving them plans and instructions.

NAWSA had spent a lot of effort educating the public about suffrage, and it had made a big impact. Women's suffrage was now a major national issue, and NAWSA was becoming the nation's largest volunteer group, with two million members. Catt used this foundation to turn NAWSA into a powerful political group.

1916: The Winning Plan

At a meeting in March 1916, Catt explained NAWSA's challenge. The Congressional Union was attracting women who only wanted a federal amendment. Southern members were upset because NAWSA was still working for a federal amendment. Catt believed that working only state-by-state was no longer enough. Some states would likely never approve women's suffrage.

Catt refocused the organization on a national suffrage amendment. However, they still continued state campaigns where success was possible.

In June 1916, suffragists put pressure on both the Democratic and Republican parties at their conventions. Catt spoke to the Republican convention. At the Democratic convention, suffragists filled the galleries to make their views known.

Both parties supported women's suffrage, but only at the state level. Catt wanted more, so she called an Emergency Convention in September 1916. This convention adopted Catt's "Winning Plan." This plan made the national suffrage amendment the top priority for the entire organization. It also created a professional lobbying team in Washington. The plan set strict rules for funding state campaigns, only supporting those with a real chance of success. Catt's plan aimed to get the women's suffrage amendment passed by 1922.

President Wilson, whose views on women's suffrage were changing, spoke at the 1916 NAWSA convention. He had voted for suffrage in New Jersey's state referendum in 1915. He spoke favorably of suffrage at the convention but did not yet fully support the federal amendment. His opponent, Charles Evans Hughes, did endorse the suffrage amendment.

Catt reorganized NAWSA's Congressional Committee and appointed Maud Wood Park as its head in December 1916. Park and her assistant Helen Hamilton Gardener created the "Front Door Lobby." This group worked openly, unlike traditional lobbyists. They set up headquarters in a mansion called Suffrage House, where lobbyists stayed and planned their daily activities.

In 1916, NAWSA bought the Woman's Journal from Alice Stone Blackwell. This newspaper, started by Lucy Stone in 1870, had been the main voice of the suffrage movement. After the purchase, it was renamed Woman Citizen and became NAWSA's official newspaper.

1917: War and Victory

In 1917, Catt received a large gift of $900,000 from Mrs. Frank (Miriam) Leslie to use for the women's suffrage movement. Catt used most of this money for NAWSA, including $400,000 to improve the Woman Citizen newspaper.

In January 1917, Alice Paul's NWP started protesting outside the White House, demanding women's suffrage. Police arrested over 200 of these "Silent Sentinels." Many went on hunger strike in prison and were treated harshly, including being fed against their will. This caused a public outcry and fueled the debate about women's suffrage.

When the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, NAWSA supported the war effort. Shaw was appointed head of the Women's Committee for the Council of National Defense, which helped coordinate war resources. Catt and two other NAWSA members were on its executive committee. The NWP, however, did not participate in the war effort.

In April 1917, Jeannette Rankin of Montana became the first woman in Congress. She had previously worked for NAWSA. Rankin voted against the declaration of war.

In November 1917, the suffrage movement won a big victory when New York, the most populated state, voted to give women the right to vote.

1918–1919: The Final Push

The House of Representatives passed the suffrage amendment for the first time in January 1918. But the Senate delayed its vote until September. President Wilson spoke to the Senate, asking them to pass the amendment as a war measure. However, the Senate defeated it by two votes.

NAWSA then started a campaign to remove four senators who had voted against the amendment. Two of them were defeated in the November elections.

NAWSA held its Golden Jubilee Convention in St. Louis, Missouri, in March 1919. President Catt suggested creating a league of women voters. A resolution was passed to form this league as a separate part of NAWSA. Its goal was to achieve full suffrage and work on laws affecting women in states where they could already vote. In June of that year, the Nineteenth Amendment was passed by Congress.

The Nineteenth Amendment Passes

After the elections, President Wilson called a special session of Congress, which passed the suffrage amendment on June 4, 1919. The next step was for three-fourths of the state legislatures to approve it.

Catt and the NAWSA board had been planning for this since April 1918. They had already set up ratification committees in state capitals. As soon as Congress passed the amendment, the federal lobbying efforts stopped, and all resources went to getting the states to ratify it. Catt felt a sense of urgency, expecting reform efforts to slow down after the war ended.

By the end of 1919, women could effectively vote for president in states that had a majority of electoral votes. Political leaders realized that women's suffrage was coming and started to support it so their parties could get credit. Both the Democratic and Republican parties endorsed the amendment in June 1920.

Former NAWSA members Kate Gordon and Laura Clay organized opposition to the amendment in the South. They had left NAWSA in 1918 because they publicly opposed a federal amendment. Only three Southern or border states—Arkansas, Texas, and Tennessee—ratified the 19th Amendment. Tennessee was the crucial 36th state needed for it to become law.

The Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, became law on August 26, 1920.

Becoming the League of Women Voters

Six months before the Nineteenth Amendment was approved, NAWSA held its last convention. At this convention, on February 14, 1920, the League of Women Voters was created as NAWSA's new form. Maud Wood Park, who had led NAWSA's Congressional Committee, became its first president. The League of Women Voters was formed to help women get more involved in public affairs and use their new right to vote. Until 1973, only women could join the league.

State Organizations Working with NAWSA

- Alabama - Alabama Equal Suffrage Association.

- Arizona - Arizona Equal Suffrage Campaign Committee

- Arkansas - Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association; and, Political Equality League

- Delaware - Delaware Equal Suffrage Association.

- Hawaii - National Women's Equal Suffrage Association of Hawai'i.

- Indiana - Women's Franchise League of Indiana

- Kentucky - Kentucky Equal Rights Association

- Maine - Maine Women's Suffrage Association.

- Nevada - Nevada Equal Franchise Society.

- New Mexico - Santa Fe chapter of NAWSA.

- North Dakota - North Dakota Votes for Women League.

- Texas - Texas Equal Suffrage Association.

- Virginia - Equal Suffrage League of Virginia

- West Virginia - West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association

See also

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Timeline of women's suffrage in the United States

- Women's suffrage organizations

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |