Matilda Joslyn Gage facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

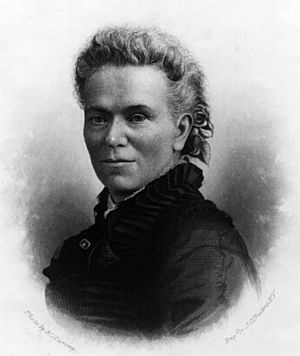

Matilda Joslyn Gage

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Matilda Electa Joslyn March 24, 1826 Cicero, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 18, 1898 (aged 71) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Occupation | abolitionist, free thinker, author |

| Notable works | Author, with Anthony and Stanton, of first three volumes of History of Woman Suffrage |

| Spouse |

Henry Hill Gage

(m. 1845) |

| Children | Maud Gage Baum, Charles Henry Gage, Helen Leslie Gage, Julia Louise Gage, Thomas Clarkson Gage |

| Relatives | Hezekiah Joslyn (father); L. Frank Baum, son-in-law |

Matilda Joslyn Gage (born March 24, 1826 – died March 18, 1898) was an important American writer and activist. She is best known for her work to help women get the right to vote, which is called women's suffrage. But she also worked hard for Native American rights, to end slavery (this was called abolitionism), and for freethought. Freethought means people should use their own reason to decide what to believe, especially about religion.

Matilda Joslyn Gage was so influential that a scientific idea, the Matilda effect, was named after her. This effect describes how women scientists sometimes don't get enough credit for their discoveries. She also had a big impact on her son-in-law, L. Frank Baum, who wrote the famous book The Wizard of Oz.

She was the youngest person to speak at the 1852 National Women's Rights Convention in Syracuse, New York. People thought she was one of the smartest and bravest writers of her time. From 1878 to 1881, she published a newspaper called National Citizen, which focused on women's issues. She worked closely with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony for many years to help women gain the right to vote. Together, they wrote the first three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage. She also wrote other books, like Woman as Inventor and Woman, Church and State.

Matilda was part of the National Woman Suffrage Association for a long time. But her ideas about women's rights became more radical than some other members liked. So, she started her own group called the Woman's National Liberal Union. This group wanted to make sure women had the right to govern themselves. It also worked to protect freedom of religion and to prevent the church and government from mixing. She led this group from 1890 until she passed away in 1898.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Matilda Electa Joslyn was born in Cicero, New York, on March 24, 1826. Her parents were Dr. Hezekiah Joslyn and Helen (Leslie) Joslyn. Her father was a very open-minded person and one of the first people to speak out against slavery. Her mother, who came from Scotland, loved history, and Matilda got that interest from her. Their home was even a safe place for people escaping slavery, part of what was called the Underground Railroad.

Matilda learned a lot from her parents at home. The smart and open environment in her house really shaped her future. She also went to the Clinton Liberal Institute in Clinton, New York.

Marriage and First Steps in Activism

On January 6, 1845, when she was 18, Matilda married Henry H. Gage. He was a merchant, and they made their home in Fayetteville, New York. She even faced legal trouble because she helped people on the Underground Railroad. This was against the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which made it a crime to help escaped slaves. In 1852, Matilda became involved in the women's rights movement when she spoke at the National Women's Rights Convention in Syracuse, New York.

Writer and Editor

Matilda Gage was very well-educated and wrote a lot. Her son-in-law, L. Frank Baum, even said she was the most talented and educated woman of her time. She wrote to many newspapers, sharing updates about the woman suffrage movement. In 1878, she bought a monthly newspaper called Ballot Box. Its editor was retiring, so Gage took over. She changed its name to The National Citizen and Ballot Box.

She explained what she wanted the paper to do:

Its main goal will be to protect women citizens' right to vote... it will be against any laws that treat groups of people unfairly... Women of all kinds will find this paper their friend.

—Matilda Joslyn Gage, "Prospectus"

Matilda was the main editor for the next three years, until 1881. She wrote many articles on different topics. Every issue had the words 'The Pen Is Mightier Than The Sword' on it. It also featured regular stories about important women in history and female inventors. Gage wrote clearly and logically, often using humor and irony. For example, when writing about laws that let a man decide who would take care of his children, even if it wasn't their mother, Gage said:

Sometimes it's better to be a dead man than a living woman.

—Matilda Joslyn Gage, "All The Rights I Want"

Her Activism

Matilda Gage once said she was "born with a hatred of oppression." This meant she strongly disliked unfair treatment of any kind.

Fighting for Women's Vote

Even though she had money problems and heart issues, she worked tirelessly for women's rights. Her work was very effective and often brilliant. Many people thought Gage was even more radical than Susan B. Anthony or Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She worked with them to write the History of Woman Suffrage.

She was the president of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) from 1875 to 1876. She also held other important roles for over twenty years. At a convention in 1876, she successfully argued against police who said their meeting was illegal. They left without causing trouble. She also represented the NWSA at major political conventions in 1880. For five years, she was president of the New York State Suffrage Association.

Because of Gage's work, New York State allowed women to vote for members of school boards. Gage made sure every woman in her area knew about this right. She wrote letters to them and even sat at the voting places to make sure no one was turned away. In 1871, Gage was part of a group of 10 women who tried to vote. She argued with officials for each woman. She also supported Victoria Woodhull and Ulysses S. Grant in the 1872 presidential election. In 1873, she defended Susan B. Anthony when Anthony was put on trial for voting in that election. Gage made strong legal and moral arguments for Anthony.

Gage tried to stop the women's suffrage movement from becoming too conservative. Susan B. Anthony mainly wanted to get the vote, but Gage felt this goal was too narrow. Some conservative women joined the movement because they thought women's votes would help with things like temperance (stopping alcohol use) and Christian political goals. They didn't support broader social changes. This conservative group was called the American Woman Suffrage Association. In 1890, these two groups merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

Stanton and Gage kept their more radical views and were against this merger. They believed it was a danger to the separation of church and state. That same year, Gage started the Woman's National Liberal Union (WNLU). She was its president until she died in 1898. This group became a place for many new and liberal ideas of the time.

Views on Religion

Matilda Gage, along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, openly criticized the Christian Church. This put her at odds with more conservative women's rights activists. Instead of saying women deserved the vote because they would make laws more moral (which some groups did), Gage argued that women deserved suffrage as a "natural right." Even with her strong opposition to the Church, Gage was religious in her own way. She helped Stanton write The Woman's Bible.

Gage was a strong opponent of the Christian church as it was controlled by men. She believed that for centuries, Christian practices had been unfair and harmful to women. She saw the Christian church as a main reason why men controlled women. She thought church teachings were used to make women seem less moral and naturally sinful. She strongly supported the idea of separation of church and state. She believed that "the greatest harm to women came from religious laws that made women obey men." In 1881, she wrote:

Believing this country is a political, not a religious, organization... the editor of the National Citizen will use all her influence against "Sabbath Laws", using the "Bible in School", and especially against adding "God in the Constitution".

In 1893, she published Woman, Church and State. This book explained how Christianity had oppressed women and strengthened patriarchy (a system where men hold most of the power). Gage later became a Theosophist, which is a spiritual philosophy. In her last years, she focused on spiritual topics like Spiritualism and Theosophy.

Witch Trials

Gage also strongly spoke out against the witch hunts that happened in the 1600s. She believed these were a way for the church to control and kill women. In her book Woman, Church & State, she argued that the church's beliefs, combined with restrictions on women by both church and government, led to the extreme witch trials. She suggested that if you replace "witches" with "women," you can better understand the oppression. Gage also believed that educated women who spoke out against male control were seen as a threat to the church and were more likely to be accused of witchcraft. In 1893, she wrote:

The witch was actually the deepest thinker, the most advanced scientist of those times. The persecution against witches was really an attack on science by the church. Since knowledge has always been power, the church feared its use in women’s hands, and aimed its deadliest blows at her.

Gage also argued that older women deserved justice for the extreme violence they faced during the 17th century witch hunts. She used strong language to show that older women were often accused of witchcraft. She implied that those accused faced a life of shame and suffering, making it rare for an elderly woman to die peacefully of old age. While her numbers might not have been perfectly accurate, Gage used her ideas about the witch hunts to criticize the Christian church's treatment of women and to demand fairness.

Native American Rights

Matilda Gage was influenced by the writings of Lewis H. Morgan and Henry Schoolcraft about Native Americans in the United States. She used her speeches and writings to speak out against the harsh treatment of Native Americans. She was angry that the U.S. government tried to force citizenship on them. This would take away their status as separate nations and their treaty rights.

In 1878, she wrote:

That the Indians have been oppressed - are now, is true, but the United States has treaties with them, recognizing them as distinct political communities, and duty towards them demands not an enforced citizenship but a faithful living up to its obligations on the part of the government.

—Matilda Joslyn Gage, "Indian Citizenship"

In her 1893 book, Woman, Church and State, she wrote about the Iroquois society. She called it a 'matriarchate', meaning women had real power. She noted that their system of tracing family through the mother's side (matrilineality) and women's property rights led to a more equal relationship between men and women. Gage spent time with the Iroquois people. They gave her the name Karonienhawi, which means "she who holds the sky." She was also welcomed into the Iroquois Council of Matrons.

Family Life

Matilda Gage lived at 210 E. Genesee St., Fayetteville, New York, for most of her life. She had five children with her husband, Henry: Charles Henry (who died as a baby), Helen Leslie, Thomas Clarkson, Julia Louise, and Maud.

Maud was the youngest child. Matilda was at first shocked when Maud said she wanted to marry L. Frank Baum, who was then just an actor and had only written a few plays. But a few minutes later, Gage started laughing. She realized that her daughter was following her own advice to think for herself. Maud gave up a chance to become a lawyer, which was rare for women at that time. Matilda spent six months of every year with Maud and Frank. Frank grew to respect Matilda greatly. Many people believe his most famous books, like The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, show her political influence.

Gage's only son and his wife had a daughter named Dorothy Louise Gage, born in Bloomington, Illinois, in 1898. Maud, who had always wanted a daughter, loved her niece very much. Sadly, the baby died in November, when she was only five months old. Maud was so sad that she needed medical care. To honor his wife's grief, Frank named the main character of his next book Dorothy Gale. In 1996, Dr. Sally Roesch Wagner, who wrote a book about Matilda Joslyn Gage, found young Dorothy's grave. A memorial was put up for the child in 1997. This Dorothy is sometimes confused with her cousin, also named Dorothy Louise Gage (1883–1889), who was the daughter of Matilda Gage's oldest surviving child, Helen.

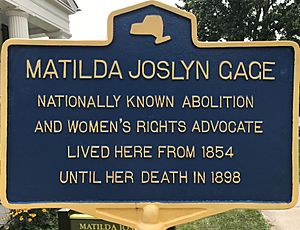

Matilda Gage passed away in the Baum family home in Chicago in 1898. She was cremated, but there is a memorial stone at Fayetteville Cemetery. It has her famous saying: "There is a word sweeter than Mother, Home or Heaven. That word is Liberty."

Her great-granddaughter was Jocelyn Burdick, who became a U.S. Senator from North Dakota.

Matilda Effect and Her Legacy

In 1993, a historian named Margaret W. Rossiter created the term "Matilda effect". She named it after Matilda Gage. This term describes when women scientists unfairly get less credit for their work than they deserve. The "Matilda effect" is the opposite of the "Matthew effect", which is when famous scientists get too much credit for new discoveries. Matilda Gage's important life was written about in books by Sally Roesch Wagner and Charlotte M. Shapiro.

In 1995, Matilda Gage was honored by being added to the National Women's Hall of Fame.

Her home in Fayetteville is now the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation. It is open to the public as a historic house museum.

In a TV movie called The Dreamer of Oz (1990), Matilda Gage was played by the actress Rue McClanahan.

Selected Writings

Matilda Gage was the editor of The National Citizen and Ballot Box from May 1878 to October 1881. She also edited The Liberal Thinker starting in 1890. These newspapers allowed her to publish many essays and opinion pieces. Here are some of her important works:

- "Is Woman Her Own?", published in The Revolution, 1868.

- "Prospectus", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, 1878.

- "Indian Citizenship", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, 1878.

- "All The Rights I Want", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, 1879.

- "A Sermon Against Woman", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, 1881.

- "God in the Constitution", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, 1881.

- Woman As Inventor, 1870.

- History of Woman Suffrage, 1881 (written with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony).

- Woman, Church and State, 1893.

See also

In Spanish: Matilda Joslyn Gage para niños

In Spanish: Matilda Joslyn Gage para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |