Woman Suffrage Procession facts for kids

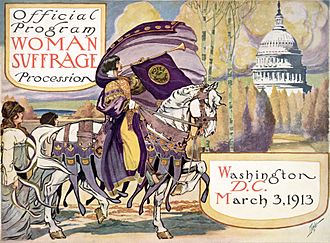

Official program for the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., March 3, 1913

|

|

| Date | March 3, 1913 |

|---|---|

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

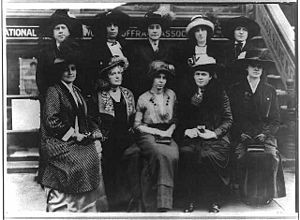

| Organised by | National American Woman Suffrage Association |

The Woman Suffrage Procession on March 3, 1913, was a huge parade in Washington, D.C. It was the first major march for women's voting rights in the city. It was also the first large, organized protest march in Washington for a political cause.

This important event was put together by two suffragists, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns. They worked for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Planning for the parade started in December 1912. The main goal of the parade, as stated in its official program, was to "protest against the current political system, which did not include women."

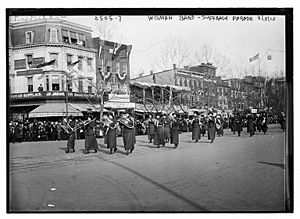

Between 5,000 and 10,000 people marched in the procession. Suffragists and their supporters walked down Pennsylvania Avenue on Monday, March 3, 1913. This was just one day before President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. Alice Paul chose this date and place to get the most attention. However, she faced problems with the D.C. police department.

The parade included floats, bands, and groups showing women at home, in school, and at work. At the Treasury Building, actors performed a special show with symbolic scenes. The parade ended with a rally at the Memorial Continental Hall. Famous speakers like Anna Howard Shaw and Helen Keller spoke there.

Before the event, there were discussions about whether black women could march. Some black women did march with their state groups. A group from Howard University also joined the parade. While it's often said black women were forced to march at the back, records show many marched with their own state or professional groups.

During the parade, the police struggled to control the huge crowd. This made it hard for the marchers to move forward. Many participants were yelled at by some people watching. But there were also many supporters. Citizens' groups and later the cavalry had to help the marchers. The police faced an investigation because they failed to keep the parade safe.

This event was the start of Alice Paul's plan to focus the women's voting rights movement on getting a national constitutional amendment. She wanted to pressure President Wilson to support this amendment. But he did not agree to their demands for many years.

The parade was shown in the 2004 movie Iron Jawed Angels. A new U.S. ten-dollar bill with images from the parade is planned for 2026.

Contents

How the Parade Started

American suffragists Alice Paul and Lucy Burns wanted to create a national plan for women's suffrage (the right to vote). They worked with the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Paul and Burns had learned about strong protest methods while working with Emmeline Pankhurst in Britain. They saw how rallies, marches, and demonstrations could be effective.

They had even been arrested and gone on hunger strikes for their activism. They were not afraid to be bold, even if it meant facing consequences. This parade would be their first big step in using these methods in America.

Paul and Burns found many suffragists who liked these stronger tactics. These included Harriot Stanton Blatch and Alva Belmont. Paul and Burns realized that women in the six states where they could already vote were a powerful group. They suggested a new plan to the NAWSA leaders in 1912. The leaders did not want to change their state-by-state approach. They also rejected the idea of holding the Democratic Party responsible.

Paul and Burns asked famous reformer Jane Addams for help. She spoke up for them. Because of this, Paul was made the head of the Congressional Committee.

Before this time, the women's voting rights movement mostly used speeches and writings. Paul believed it was time to add a strong visual element to their campaign. She wanted to create a lasting impact. She felt it was time for women to stop asking for the right to vote and start demanding it. While suffragists had marched in many cities, this would be the first big political demonstration in Washington, D.C. The only similar event before was by Coxey's Army in 1894, a group of men protesting unemployment.

When Paul and Burns took over the Congressional Committee, it had a very small budget. But with them in charge, the committee pushed hard for a national voting rights amendment. By the end of 1913, Paul reported that the committee had raised and spent over $25,000 for the cause.

Paul and Burns convinced NAWSA to support a huge suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. It would happen at the same time as newly elected President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. The NAWSA leaders gave the entire event to Paul's committee. They organized volunteers, planned, and raised money with little help from NAWSA.

Getting Ready for the Parade

Planning Committees and Finding Marchers

Once the NAWSA board approved the parade in December 1912, they appointed Dora Lewis, Mary Ritter Beard, and Crystal Eastman to the committee. Alice Paul arrived in Washington, D.C., in December 1912 to start organizing. By the first committee meeting in January 1913, over 130 women showed up to help.

Local suffragists like Florence Etheridge and teacher Elsie Hill helped Paul. Elizabeth Thacher Kent, the former committee chair, helped Paul and Burns connect with people in Washington. Paul also recruited Emma Gillett as treasurer and Helen Hamilton Gardener for publicity. Belva Lockwood, who had run for president in 1884, also attended.

Paul hired Hazel MacKaye to design professional floats and symbolic scenes. The parade was officially called the Woman Suffrage Procession. Its goal was to "march in a spirit of protest against the current political system, from which women are excluded." Doris Stevens, who worked closely with Paul, said the parade was meant to show that "women wanted to vote."

The date, March 3, was chosen carefully. It was the day before President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. This timing would make sure he knew that women's voting rights would be a key issue during his time in office. It also guaranteed a large audience and lots of publicity. Many people worried about the weather or getting enough marchers quickly. But Washington had people from all states, including wives of congressmen, who could represent their states.

To save money for publicity, the committee made it clear that groups joining the parade had to pay for their own travel and lodging.

Parade Route and Safety

Alice Paul wanted the parade route to have the biggest impact. She asked for a permit to march down Pennsylvania Avenue. This route would go from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building, then past the White House, and end at Continental Hall.

The D.C. police chief, Major Richard H. Sylvester, offered a different route through a residential area. He said Pennsylvania Avenue was too rough. Paul was not happy with this. She took her request to the city commissioners and the newspapers. Eventually, they agreed to her chosen route. Elsie Hill also put pressure on Sylvester through her father, who was in Congress.

The presidential inauguration brought a huge number of visitors. Media guessed there would be a quarter to half a million people. Paul worried if the police could handle such a crowd. Her worries turned out to be true. Sylvester only offered 100 officers, which Paul thought was not enough. She tried to get help from President William Howard Taft, who sent her to the Secretary of War.

A week before the parade, Congress passed a rule telling D.C. police to stop all traffic on the parade route. They also had to prevent any interference. Paul found someone with political connections, Elizabeth Selden Rogers. She asked her brother-in-law, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, for cavalry (soldiers on horseback) for extra safety. He first said no, but later agreed to have troops ready in case of an emergency.

Changing Anti-Suffrage Ideas

Paul cleverly chose to highlight beauty, femininity, and traditional female roles in the parade. The parade's theme was "Ideals and Virtues of American Womanhood." Anti-suffragists often claimed that giving women the vote would threaten these qualities. Paul wanted to show that women could be all these things and still be smart and capable of voting and holding other roles in society.

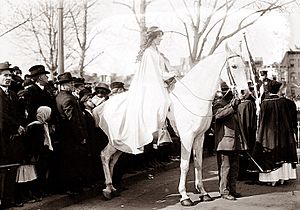

She wanted to prove that being attractive and professionally talented were not separate things. These ideas were shown by choosing Inez Milholland as the parade's herald. Milholland was a labor lawyer known as "the most beautiful suffragette." She had led a suffrage march in New York the year before.

The Parade Day

The Marchers Line Up

News reports said the suffrage parade had become more interesting than the inauguration itself. Special trains brought spectators from other cities, adding to the crowds. The parade's newness attracted huge interest across the eastern U.S. As marchers gathered near the Peace Monument, police began roping off parts of the route. But even before the parade started, the ropes were breaking. The crowd was so big that President-elect Wilson was surprised there was no one to greet him when he arrived.

Jane Walker Burleson, on horseback, led the parade as Grand Marshal. She was followed by a model of the Liberty Bell from Philadelphia. Right behind her was the herald, Inez Milholland, on a white horse. She wore a pale-blue cape over a white suit. Her banner said "Forward into Light."

Next came a wagon with a bold message: "We Demand An Amendment To The Constitution Of The United States Enfranchising The Women Of This Country." After that was the national board of the NAWSA, led by Anna Howard Shaw.

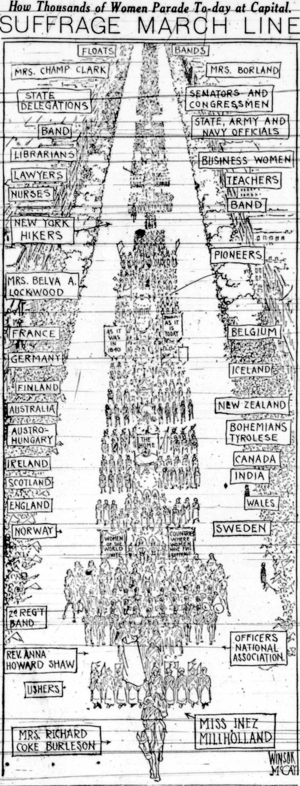

To make the parade visually stunning, Paul assigned a color scheme to each group of marchers. The different colors showed women moving into the light of the future from the darkness of the past. To add excitement, Paul included "26 floats, 6 golden chariots, 10 bands, 45 captains, 200 marshals, 120 pages, 6 mounted heralds, and 6 mounted brigades." Estimates of marchers ranged from 5,000 to 10,000.

The first section had marchers and floats from countries where women already had the right to vote, like Norway and Australia. The second section showed historical scenes from the suffrage movement. Then came a float showing women inspiring girls. Other floats showed men and women working together at home and in different jobs. One float showed a man carrying government on his shoulders while a woman stood helpless beside him.

Groups of women representing traditional roles like motherhood and homemaking marched to show that suffragists were not just "sexless working women." Then came professional women, including nurses, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, and the PTA. Finally, women in non-traditional careers like lawyers and artists marched.

After a float showing the Bill of Rights, a banner displayed the nine states where women could vote in bright colors. The other states were shown in black. Another banner quoted Abraham Lincoln: "No Country Can Exist Half Slave and Half Free," suggesting that women without the vote were like slaves. Women from the suffrage states carried colorful banners on chariots.

One famous group was the pilgrims led by "General" Rosalie Jones. These hikers walked over 200 miles (320 km) from New York City to Washington in sixteen days. Their journey got a lot of press, and a large crowd greeted them when they arrived.

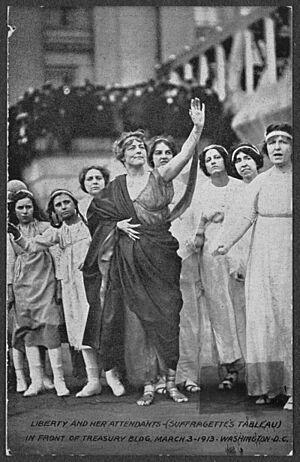

Symbolic Performances

At the same time as the parade, a symbolic performance took place on the steps of the Treasury Building. This show was written by Hazel MacKaye and directed by Glenna Smith Tinnin. Silent actors performed scenes showing patriotism and civic pride. The audience would recognize this style from other holiday events. MacKaye dressed the women in toga-like costumes. Symbolic music played during each scene.

The show began with trumpet calls. The first scene featured Columbia, a symbol of America, who came forward as "The Star-Spangled Banner" played. She called Liberty, Charity, Justice, Hope, and Peace to join her. In the final scene, Columbia watched over them all as they waited for the suffragist parade to arrive. By creating this powerful drama, Alice Paul made the American suffrage movement stand out.

Important People in the Parade

Some of the women listed below were already famous, while others became well-known later. Most names come from the official parade program.

- Dr. Nellie V. Mark led the professional women of Maryland.

- Jeannette Rankin, from Montana, marched with her state. Four years later, she became a U.S. Representative.

- Charlotte Anita Whitney marched with the NAWSA officers.

- Mary Ware Dennett, from New York, also marched with the NAWSA board.

- Susan Walker Fitzgerald, from Boston, later served in the Massachusetts legislature.

- Katherine Dexter McCormick, NAWSA treasurer, became a notable giver of money to good causes.

- Harriet Burton Laidlaw, from New York, was a political activist.

- Abby Scott Baker, a D.C. resident, organized the floats for foreign countries.

- Dorothy Bernard, an actress, organized the group of actresses.

- Jane Delano, founder of the American Red Cross Nursing Service, organized the nurses' group.

- Carrie Clifford, an American author and civil rights activist.

- Lavinia Dock, a pioneer in nursing education, helped with the nursing section.

- Jane Addams was a famous social worker and feminist.

- Fola La Follette, a Broadway actress, led the actress group.

- Lillian Wald, founder of community nursing, led the nurses section.

- Miss Georgia Simpson, a philologist, was the first African-American woman to get a PhD in the U.S.

- Ellen Spencer Mussey, a D.C. attorney, led women lawyers.

- Mary Johnston, a popular writer, spoke at the rally.

- Estelle Willoughby Ions, a composer, led the musicians section.

- Elizabeth Thacher Kent organized the bands.

- Julia Lathrop, Chief of the U.S. Children's Bureau, was the first woman to head a federal bureau. She marched with the banner for Women in Government Service.

- Annie Jenness Miller, a clothing designer, organized the grandstand committee.

- Genevieve Clark Thomson led the Missouri delegation.

- Harriet Taylor Upton led the delegation from Ohio.

- Florence Fleming Noyes, a dancer, planned all the symbolic performances.

Safety Problems

The parade and performances were supposed to start at 3 p.m. But the parade didn't begin until 3:25 p.m. At the front were police cars and six mounted officers. By the time the parade reached 5th Street, the crowd had completely blocked the avenue. The police escort seemed to disappear into the crowd.

Inez Milholland and others on horseback used their animals to push back the crowds. Alice Paul and other committee members brought cars to the front to help clear a path. The police had done little to open the route as ordered by Congress. Police chief Sylvester, who was waiting for President Wilson, heard about the problem. He called for the cavalry unit on standby. But the soldiers didn't arrive until around 4:30 p.m. They then helped the parade finish its route.

Many people, mostly men, surged into the street. Some were yelling insults, while others were supportive. Parade marshal Burleson and other women felt scared by the hostile shouts. The Evening Star newspaper in Washington wrote about positive reactions to the parade. The huge crowd led to people being trampled. More than 200 people were treated for injuries at hospitals.

At one point, Paul said the police were overwhelmed and not enough officers were assigned. But she soon changed her mind to get more publicity for her cause. The police did arrest some people for crossing the ropes.

Before the cavalry arrived, other people helped control the crowd. Sometimes, marchers had to walk in single file to move forward. Boy Scouts helped push back spectators. A group of soldiers linked arms to hold people back. Some black drivers from the floats also helped. The Massachusetts and Pennsylvania national guards stepped in. Finally, boys from the Maryland Agricultural College formed a human barrier. They protected the women from the crowd and helped them reach their destination.

Rally at Continental Hall

The parade ended with a meeting at the Memorial Continental Hall. Speakers included Anna Howard Shaw, Carrie Chapman Catt, Mary Johnston, and Helen Adams Keller. Anna Howard Shaw spoke about the police's failure to protect the marchers. She said she was ashamed of the nation's capital but praised the marchers. She also realized that the police failures could be used to help the suffragists' cause.

What Happened Next

President Wilson's Response

Alice Paul and the Congressional Union asked President Wilson to push Congress for a federal amendment. They visited the White House shortly after the parade and several times later. He first said he had never thought about it. But he had told a Colorado group in 1911 that he was considering it. He promised to think about it but did not act. Eventually, he said there was no time for women's voting rights on his agenda.

The women wanted Wilson to make his party support voting rights laws. He claimed he had no power over his party in Congress. However, for issues he thought were important, he did use his influence.

When asked if it was wrong to push Wilson for his stance, Paul said it was important for the public to know his position. This way, they could use it against him when it was time to pressure the Democrats during an election. It took until 1918 for Wilson to finally change his mind about the suffrage amendment.

Impact on the Women's Voting Rights Movement

Alice Paul's leadership in the American suffrage movement began with the 1913 parade. This event brought back the push for a federal women's voting rights amendment. This cause had been ignored by the NAWSA for a while. Just over a month after the parade, the Susan B. Anthony amendment was brought up again in Congress. For the first time in decades, it was discussed.

The demonstration on Pennsylvania Avenue was the start of Paul's other big events. These actions, along with those by the NAWSA, led to the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1919. It was officially approved in 1920.

Paul's focus on a federal amendment was very different from NAWSA's state-by-state approach. This led to a disagreement between Paul's committee and the national board. The committee separated from the NAWSA and became the Congressional Union. The Congressional Union later became part of the National Woman's Party, also led by Paul, in 1916.

Other Interesting Facts

In Movies

The Woman Suffrage Procession was shown in the 2004 film Iron Jawed Angels. This movie tells the story of Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and the National Woman's Party. It shows how they worked to get the 19th Amendment passed, which gave all American women the right to vote.

U.S. Money

On April 20, 2016, the Treasury Secretary announced plans for the back of the new $10 bill. It would feature an image of the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession. This parade passed the Treasury Department steps where the symbolic performances happened. The new bill will also honor many leaders of the suffrage movement. These include Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul. The front of the new $10 bill will still have Alexander Hamilton's picture. New designs for $5, $10, and $20 bills were supposed to be shown in 2020. Later, it was said the new $10 bill would not be ready until 2026.

Issues with Race

The women's voting rights movement started in the 1800s. It was linked to the movement to end slavery. But by the early 1900s, the goal of voting rights for everyone was affected by widespread racism in the United States. Earlier suffragists thought the two issues could be connected. But the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment and Fifteenth Amendment created a split. These amendments gave voting rights to black men first, before all men and women. In 1903, the NAWSA officially adopted a policy that aimed to please Southern U.S. suffrage groups.

Because segregation was common, black people formed their own groups to fight for equal rights. Many were college educated and wanted political power. The 50th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation (which freed slaves) was also in 1913. This gave them more reason to march in the suffrage parade.

Members of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority asked for a place in the college women's section for the women of Howard University. Letters show discussions about giving the Howard women a good place in the march. Alice Paul had asked Elsie Hill to recruit the Howard women.

However, some people tried to convince Paul that including black marchers was a bad idea. They said Southern groups might leave the march. Paul tried to keep news about black marchers quiet. But when the Howard group announced they would participate, the public learned about the conflict. One newspaper said Paul told some black suffragists that NAWSA believed in equal rights for "colored women." But she also said some Southern women would likely object. An organization source said the official stance was to "permit negroes to march if they cared to."

Alice Paul later remembered that a solution was found. A Quaker leader of the men's section suggested the men march between the Southern groups and the Howard University group.

While Paul remembered a compromise, reports in the NAACP paper, The Crisis, show things happened differently. Black women protested the plan to separate them. What is clear is that some groups tried to segregate their delegations on parade day. For example, a last-minute instruction asked Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the only black member of the Illinois group, to march with a separate black group at the back. Wells-Barnett eventually rejoined the Illinois delegation as the parade moved. In the end, black women marched in several state groups, including New York and Michigan. Some joined their co-workers in professional groups. Black men also drove many of the floats. The people watching did not treat the black participants differently. The Delta Sigma Theta sorority members were placed at the very end of the parade.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |