Ida B. Wells facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ida B. Wells

|

|

|---|---|

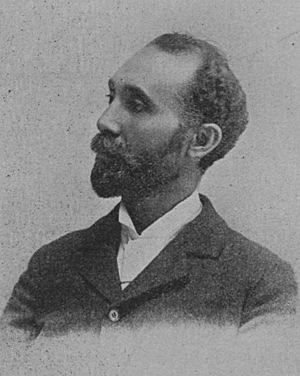

Wells, c. 1893

|

|

| Born |

Ida Bell Wells

July 16, 1862 |

| Died | March 25, 1931 (aged 68) Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

|

| Burial place | Oak Woods Cemetery |

| Other names |

|

| Education |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 6, including Alfreda Duster |

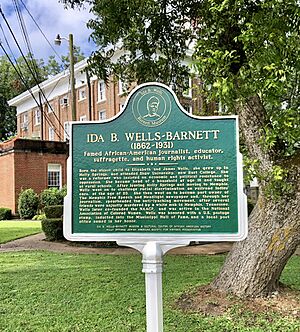

Ida B. Wells (born Ida Bell Wells-Barnett) was an important American journalist, teacher, and leader in the civil rights movement. She was born on July 16, 1862, and passed away on March 25, 1931. She helped start the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Ida B. Wells spent her life fighting against unfair treatment and violence. She worked hard for equal rights for African Americans, especially women. Many people saw her as the most famous Black woman in the United States during her time.

Ida B. Wells was born into slavery in Holly Springs, Mississippi. She became free because of the Emancipation Proclamation during the American Civil War. When she was 14, a terrible yellow fever epidemic took her parents and baby brother. She started working to keep her remaining family together, with help from her grandmother. Later, she moved to Memphis, Tennessee with some of her siblings. There, she found better pay as a teacher. Soon, Wells became a co-owner and writer for the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight newspaper. She wrote about unfair racial rules and treatment.

In the 1890s, Wells wrote about lynching in the United States. She published articles and pamphlets like Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases. She showed that lynching was a cruel act used by white people in the South. It was meant to scare and control African Americans who were gaining economic and political power. Wells' writings helped people understand the truth about this violence. She was a respected voice in the African American community. Because of her brave reporting, a white mob destroyed her newspaper office. Facing threats, Wells moved to Chicago. In 1895, she married Ferdinand L. Barnett and started a family. She continued to write, speak, and organize for civil rights and women's rights throughout her life.

Ida B. Wells was very open about her beliefs as a Black female activist. She often faced criticism, even from other civil rights and women's suffrage movement leaders. She was active in women's rights and helped create several important women's groups. Wells was a skilled speaker and traveled around the country and the world giving lectures. She died on March 25, 1931, in Chicago. In 2020, she received a special Pulitzer Prize award after her death. This award was for her "outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching."

Contents

Early Life and Family

Ida Bell Wells was born on July 16, 1862, near Holly Springs, Mississippi. She was the oldest child of James Madison Wells and Elizabeth "Lizzie" (Warrenton). Her father, James, was the son of a white man and an enslaved Black woman. He learned carpentry and worked for money, which went to his slaveholder. Lizzie was sold away from her family in Virginia. She tried to find them after the American Civil War but could not. Before they were freed, Wells' parents were enslaved by Spires Boling. The family lived in a building now called the Bolling–Gatewood House, which is now the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum.

After slavery ended, James Wells became a leader at Shaw College (now Rust College). He was a strong supporter of the Republican Party and worked for Black political rights. He started a successful carpentry business in 1867. His wife, Lizzie, was known as a great cook.

Ida B. Wells was one of eight children. She went to Rust College, a historically Black college in Holly Springs. In September 1878, a yellow fever epidemic killed both of Ida's parents and one of her siblings. Ida was visiting her grandmother's farm and was safe.

After the funerals, friends and family wanted to separate the five remaining Wells children into foster homes. Ida refused this idea. To keep her younger siblings together, she found work as a teacher in a rural Black elementary school. Her grandmother, Peggy Wells, and other relatives helped care for her siblings during the week while Ida taught.

Around two years later, her grandmother Peggy had a stroke, and her sister Eugenia died. In 1883, Wells and her two youngest sisters moved to Memphis to live with their aunt, Fanny Butler. Memphis was about 56 miles (90 km) from Holly Springs.

Early Career and Fighting Segregation

It is with no pleasure that I have dipped my hands in the corruption here exposed ... Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so.

Soon after moving to Memphis, Wells got a job teaching in the Shelby County school system. During her summer breaks, she took classes at Fisk University in Nashville. She also attended LeMoyne–Owen College in Memphis. Wells had strong opinions, especially about women's rights. At age 24, she wrote that she would not flatter men to get what she wanted.

On May 4, 1884, a train conductor told Wells to leave her seat in the first-class ladies' car. He wanted her to move to the crowded smoking car. The year before, the U.S. Supreme Court had allowed racial segregation on trains. Wells refused to move, and the conductor and two men dragged her off the train. Wells wrote about this event for The Living Way, a Black church newspaper, which made her known in Memphis. She hired a Black lawyer to sue the railroad. When that lawyer was paid off by the railroad, she hired a white lawyer.

She won her case on December 24, 1884, and was awarded $500. However, the railroad company appealed, and the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the ruling in 1887. They said Wells' goal was to cause trouble for the lawsuit. Wells was ordered to pay court costs. She was very disappointed, saying, "O God, is there no ... justice in this land for us?"

While still teaching, Wells became more active as a journalist. She became an editor for the Evening Star and wrote weekly articles for The Living Way under the pen name "Iola." Her articles criticized racist Jim Crow policies. In 1889, she became editor and co-owner of The Free Speech and Headlight, a Black-owned newspaper.

In 1891, the Memphis Board of Education fired Wells from her teaching job. This was because she wrote articles criticizing the conditions in Black schools. She was upset but not defeated. She focused all her energy on writing for The Living Way and the Free Speech and Headlight.

Speaking Tours in Britain

Wells traveled to Britain twice, in 1893 and 1894, to campaign against lynching. She hoped to get support from Britain to shame America for its racist practices. She and her supporters saw these trips as a chance to reach white audiences, which was hard to do in America. Wells noted that her ocean journeys were important because of the history of the Middle Passage and Black women's identity. She found people in Britain who were shocked by reports of lynching in America.

Catherine Impey and Isabella Fyvie Mayo invited Wells for her first British tour. Impey was a Quaker who published an anti-slavery journal. Mayo was a writer. They first asked Frederick Douglass, but he suggested Wells instead. Wells eagerly accepted. In 1894, before her second trip to Britain, Wells visited William Penn Nixon, editor of the Daily Inter Ocean. This was the only major white newspaper that spoke out against lynching. Nixon asked her to write for his paper while in England. She became the first African American woman to be a paid writer for a mainstream white newspaper.

Wells toured England, Scotland, and Wales for two months. She spoke to thousands of people and inspired a moral movement among the British. On her first tour, she used her pamphlet Southern Horrors and showed shocking photos of lynchings. On May 17, 1894, she spoke in Birmingham. On June 25, 1894, she gave a powerful speech in Bradford.

On the last night of her second tour, the London Anti-Lynching Committee was formed. This was likely the first anti-lynching group in the world. Important people like the Duke of Argyll and the Archbishop of Canterbury were members.

Wells' tours in Britain received a lot of attention in British and American newspapers. Many American articles attacked her personally instead of reporting on her anti-lynching work. The New York Times called her "a slanderous and nasty-minded Mulatress." Despite these attacks, Wells gained wide recognition and support for her cause around the world. Her tours even influenced British textile makers to temporarily stop buying cotton from the South. This pressured Southern businessmen to speak out against lynching.

Marriage and Family Life

On June 27, 1895, Ida B. Wells married attorney Ferdinand L. Barnett in Chicago. Barnett was a widower with two sons. He was a well-known lawyer, civil rights activist, and journalist in Chicago. Like Wells, he spoke out against lynchings and for the rights of African Americans. Wells and Barnett met in 1893 while working on a pamphlet. This pamphlet protested the lack of Black representation at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Barnett had started The Chicago Conservator, Chicago's first Black newspaper, in 1878. Wells began writing for the paper in 1893, later owned part of it, and became its editor after marrying Barnett.

Wells' marriage to Barnett was a strong partnership. Both were journalists and activists who cared deeply about civil rights. Their daughter, Alfreda Duster, said they had "like interests" and their careers were "intertwined." This close working relationship was unusual for a married couple at that time.

Besides Barnett's two sons from his first marriage, they had four more children: Charles Aked Barnett (born 1896), Herman Kohlsaat Barnett (born 1897), Ida Bell Wells Barnett, Jr. (born 1901), and Alfreda Marguerita Barnett (born 1904). Charles Aked's middle name came from Charles Frederic Aked, a British pastor who supported Wells' anti-lynching work.

Wells started writing her life story, Crusade for Justice, in 1928, but she never finished it. Her daughter, Alfreda Barnett Duster, later edited and published it in 1970. In her book, Wells wrote about the challenge of balancing her family life and her work. She continued to work after her first child was born, even traveling with baby Charles. She tried to be both a mother and a national activist.

Wells also started Chicago's first kindergarten for Black children. It was located in the Bethel AME Church. This shows how her public work and personal life were connected. Her great-granddaughter, Michelle Duster, noted that when Wells' older children were ready for school, she saw that Black children did not have the same chances. So, Wells decided, "Well since it doesn't exist, we'll create it ourselves."

African American Leadership and Organizing

Frederick Douglass, a famous civil rights leader, praised Wells' work. He helped her and sometimes gave her money for her investigations. When he died in 1895, Wells was very well known. However, many people were unsure about a woman leading Black civil rights at a time when women were not usually seen as leaders. Some other leaders, like Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois, sometimes thought Wells was too radical.

Wells met and worked with these leaders, but they also had disagreements. For example, there are different stories about why Wells' name was not on the first list of founders for the NAACP. Du Bois said Wells chose not to be included. But Wells wrote in her autobiography that Du Bois purposely left her out.

Organizing in Chicago

After settling in Chicago, Wells continued her anti-lynching work. She also focused more on the civil rights of all African Americans. She worked with national leaders to protest a big exhibition. She was active in the national women's club movement. She even ran for the Illinois State Senate. She was also very passionate about women's rights and the right to vote. She spoke out for women to have equal chances and succeed in the workplace.

Wells was an active member of the National Equal Rights League (NERL). She represented them when asking President Woodrow Wilson to end unfair treatment in government jobs. In 1914, she led NERL's Chicago office.

World's Columbian Exposition

In 1893, the World's Columbian Exposition was held in Chicago. Wells, along with Frederick Douglass and other Black leaders, organized a boycott of the fair. They did this because the fair did not show enough achievements by African Americans. Wells, Douglass, Irvine Garland Penn, and Ferdinand L. Barnett wrote a pamphlet called The Reason Why: The Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition. This pamphlet explained the progress of Black people since arriving in America and exposed the reasons for lynchings in the South. Wells later said that over 20,000 copies of the pamphlet were given out at the fair. That year, she started working with The Chicago Conservator, the oldest African American newspaper in the city.

Women's Clubs and Community Work

Living in Chicago in the late 1800s, Wells was very involved in the women's club movement. In 1893, she started The Women's Era Club, the first civic club for African American women in Chicago. She asked Mary Jane Richardson Jones, a respected Chicago activist, to lead the club in 1894. This club was later renamed the Ida B. Wells Club in her honor. In 1896, Wells helped found the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs. After her death, the Ida B. Wells Club worked to have a housing project in Chicago named after her. They succeeded in 1939, making it the first housing project named after a woman of color. Wells also helped organize the National Afro-American Council and was its first secretary.

Wells received a lot of support from other activists and women in clubs. Frederick Douglass praised her, saying, "You have done your people and mine a service. ...What a revelation of existing conditions your writing has been for me."

However, Wells also became a controversial figure among women's clubs. In 1899, when the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs planned to meet in Chicago, local organizers said they would not cooperate if Wells was included. When Wells learned that Mary Church Terrell, the association's president, agreed to exclude her, she called it "a staggering blow."

School Segregation Fight

In 1900, Wells was very angry when the Chicago Tribune suggested having separate schools for Black and white students. Because of her experience teaching in segregated schools in the South, she wrote to the newspaper's publisher. She explained how segregated schools failed and how integrated schools succeeded. She then went to his office to argue her point. Still not satisfied, she got help from social reformer Jane Addams. Wells and the group she formed with Addams are credited with stopping the plan for an officially segregated school system in Chicago.

Working for the Right to Vote

Negro Fellowship League

In 1908, Wells, her husband, and some friends started the Negro Fellowship League (NFL). This was the first Black settlement house in Chicago. It was a place for young Black men to read, use a library, and find shelter. At that time, the local Young Men's Christian Association did not allow Black men to join. The NFL also helped new arrivals from the Southern States find jobs, especially during the Great Migration. The NFL supported women's right to vote and the Republican Party in Illinois.

Alpha Suffrage Club

After a new state law gave women some voting rights, Wells focused on Black women's right to vote in Chicago. The Illinois Presidential and Municipal Suffrage Bill of 1913 allowed women to vote for president, mayor, and most local offices. Illinois was the first state east of the Mississippi River to give women these voting rights.

Because of this new law, Wells and her white friend Belle Squire started the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago on January 30, 1913. This was one of the most important Black suffrage groups in Chicago. It aimed to help all women get the right to vote, teach Black women about civic matters, and elect African Americans to city offices. Two years later, the club helped elect Oscar Stanton De Priest as Chicago's first African American alderman.

As Wells and Squire were forming the Alpha Club, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) planned a suffrage parade in Washington D.C. In 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson became president, women from all over the country marched to demand the right to vote. Wells and a group from Chicago attended. On the day of the march, the head of the Illinois group told Wells' delegates that NAWSA wanted "to keep the delegation entirely White." All African American suffragists, including Wells, were told to march at the end of the parade in a "colored delegation."

Instead of going to the back, Wells waited with the crowd. As the white Illinois delegation passed, she stepped in and linked arms with her white friends, Belle Squire and Virginia Brooks. She marched with them for the rest of the parade. This showed, as The Chicago Defender reported, that the women's civil rights movement was for everyone.

From Activist to Political Candidate

During World War I, the U.S. government watched Wells closely. They called her a dangerous "race agitator." She did not let this stop her. She continued her civil rights work with people like Marcus Garvey and Madam C. J. Walker. In 1917, Wells wrote reports for the Chicago Defender about the East St. Louis Race Riots. After almost 30 years, Wells returned to the South in 1921. She investigated and wrote a report about the Elaine massacre in Arkansas.

In the 1920s, she fought for African American workers' rights. She urged Black women's groups to support the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. However, in 1924, she lost the presidency of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs to Mary McLeod Bethune. To address problems for African Americans in Chicago, Wells started the Third Ward Women's Political Club in 1927. In 1928, she tried to become a delegate to the Republican National Convention but lost. She became less supportive of the Republican Party because she felt the Hoover administration did not do enough for civil rights. In 1930, Wells ran for a seat in the Illinois Senate as an Independent but did not win.

Legacy and Honors

Since Wells' death, interest in her life has grown, especially with the rise of the civil rights movement in the mid-1900s. Many awards have been created in her name by groups like the National Association of Black Journalists and Northwestern University. The Ida B. Wells Memorial Foundation and the Ida B. Wells Museum work to keep her memory alive. In her hometown of Holly Springs, Mississippi, there is an Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum that shares African American history.

In 1941, a public housing project in Chicago was named the Ida B. Wells Homes in her honor. These buildings were taken down in 2011.

In 1988, she was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame and the Chicago Women's Hall of Fame. Molefi Kete Asante included Wells in his list of 100 Greatest African Americans in 2002. In 2011, Wells was honored by the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame for her writings.

On February 1, 1990, the U.S. Postal Service released a 25¢ stamp honoring Wells. The stamp shows a picture of Wells from the 1890s. She was the 25th African American and fourth African American woman to be featured on a U.S. postage stamp.

In 2006, the Harvard Kennedy School ordered a portrait of Wells. In 2007, the Ida B. Wells Association was started at the University of Memphis. This group helps students discuss important ideas about the African American experience. The Philosophy Department at the University of Memphis has held an Ida B. Wells conference every year since 2007.

On February 12, 2012, Mary E. Flowers of the Illinois House of Representatives proposed a resolution. It honored Ida B. Wells by declaring March 25, 2012, as Ida B. Wells Day in Illinois.

In August 2014, Wells was featured on the BBC Radio 4 show Great Lives. On July 16, 2015, which would have been her 153rd birthday, she was honored with a Google Doodle.

In 2016, the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting was started in Memphis, Tennessee. This group encourages minority journalists to report on injustices. It was created with support from the Open Society Foundations, Ford Foundation, and CUNY Graduate School of Journalism.

In 2018, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened. It includes a special area dedicated to Wells, with her quotes and a stone with her name.

On March 8, 2018, The New York Times published a belated obituary for her. This was part of a series called "Overlooked," which aimed to recognize notable women who had been ignored in the newspaper's past obituaries.

In July 2018, Chicago's City Council renamed Congress Parkway as Ida B. Wells Drive. It is the first street in downtown Chicago named after a woman of color.

On February 12, 2019, a blue plaque was unveiled in Birmingham, England. It marked the site of 66 Gough Road, where Wells stayed in 1893 during her British lecture tour.

On July 13, 2019, a marker for her was unveiled in Holly Springs, Mississippi. It was dedicated by the Wells-Barnett Museum.

In 2019, a new middle school in Washington, D.C., was named in her honor. On November 7, 2019, a Mississippi Writers Trail marker was placed at Rust College, honoring Ida B. Wells.

On May 4, 2020, she received a special Pulitzer Prize award after her death. It was for her "outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching." The Pulitzer Prize board also announced it would donate at least $50,000 to support Wells' mission.

In 2021, a public high school in Portland, Oregon, was renamed Ida B. Wells High School.

Monuments Honoring Ida B. Wells

In 2021, Chicago built a monument to Wells in the Bronzeville neighborhood. It is near where she lived and close to the site of the former Ida B. Wells Homes housing project. The monument is called The Light of Truth Ida B. Wells National Monument. It is based on her quote: "the way to right wrongs is to cast the light of truth upon them." Sculptor Richard Hunt created it.

Also in 2021, Memphis dedicated a new Ida B. Wells plaza with a life-sized statue of Wells. The monument is next to the historic Beale Street Baptist Church, where Wells published the Free Speech newspaper.

Ida B. Wells in Media

- In 1949, the radio show Destination Freedom told parts of her life story in an episode called "Woman with a Mission."

- The PBS documentary series American Experience aired "Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice" on December 19, 1989. Toni Morrison read parts of Wells' memoirs in the film.

- In 1995, the play In Pursuit of Justice: A One-Woman Play About Ida B. Wells was produced. It used events and speeches from Wells' autobiography.

- In 1999, a reading of the play Iola's Letter was performed at Howard University. The play was inspired by Wells' anti-lynching work in Memphis in 1892.

- Wells' life is the subject of Constant Star (2002), a musical play by Tazewell Thompson.

- Adilah Barnes played Wells in the 2004 film Iron Jawed Angels. The film shows Wells ignoring orders to march in a segregated group during the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913. Instead, she joined her white colleagues.

See also

In Spanish: Ida B. Wells para niños

In Spanish: Ida B. Wells para niños