Marcus Garvey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Right Excellent

Marcus Garvey

ONH

|

|

|---|---|

Garvey photographed in 1924

|

|

| Born |

Marcus Mosiah Garvey

17 August 1887 Saint Ann's Bay, Colony of Jamaica

|

| Died | 10 June 1940 (aged 52) |

| Alma mater | Birkbeck, University of London |

| Occupation | Publisher, journalist |

| Known for | Activism, black nationalism, Pan-Africanism |

| Spouse(s) |

Amy Ashwood

(m. 1919; div. 1922) |

| Children | 2 |

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr. ONH (17 August 1887 – 10 June 1940) was a Jamaican leader, publisher, and journalist. He started the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL), often called UNIA. Through this group, he worked to unite black people around the world. His ideas, known as Garveyism, focused on black pride and Pan-Africanism.

Garvey grew up in a well-off Afro-Jamaican family in Saint Ann's Bay. As a teenager, he learned the printing trade. In Kingston, he became involved in trade unionism. He also lived for a short time in Costa Rica, Panama, and England. After returning to Jamaica, he founded the UNIA in 1914. In 1916, he moved to the United States and opened a UNIA branch in New York City's Harlem area.

Garvey believed in unity for people of African descent everywhere. He wanted to end European colonial rule in Africa and unite the continent politically. He imagined a strong, unified Africa. He also supported the Back-to-Africa movement, encouraging some black people to move to Africa. His ideas became very popular, and UNIA grew quickly. However, his views on racial separation caused disagreements with other black leaders who wanted racial integration.

Garvey believed black people needed to be financially independent. He started several businesses in the U.S., including the Negro Factories Corporation and the Negro World newspaper. In 1919, he became president of the Black Star Line, a shipping company. It aimed to connect North America and Africa and help African Americans move to Liberia. In 1923, Garvey faced legal issues for selling company stock. He was sent to prison for almost two years. Many people thought his trial was unfair.

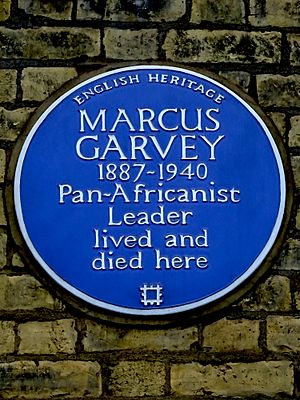

After his release, he was sent back to Jamaica in 1927. In Kingston, he started the People's Political Party in 1929 and served as a city councillor. As UNIA faced money problems, he moved to London in 1935. He died there in 1940. In 1964, his body was brought back to Jamaica and reburied in Kingston's National Heroes Park. In Jamaica, he is seen as a national hero. His ideas greatly influenced movements like Rastafari, the Nation of Islam, and the Black Power Movement.

Contents

Early Life and Travels

Childhood in Jamaica: 1887–1904

Marcus Mosiah Garvey was born on 17 August 1887, in Saint Ann's Bay, a town in the British colony of Jamaica. In Jamaica at that time, society had a system where skin color affected a person's place. Garvey was a black child of full African descent, which put him at the lower end of this system. His family, however, was better off than many of their neighbors.

His father, Marcus Garvey, was a stonemason. His mother, Sarah Richards, was a domestic worker. Marcus was the youngest of their four children, though two died young. His father owned books and taught himself many things. He was also a strict parent.

Marcus went to a local church school until he was 14. His family could not afford more education for him. When not in school, he worked on his uncle's farm. In 1901, Marcus became an apprentice to his godfather, a local printer. By 1904, he was working at the printer's new branch in Port Maria.

Starting Work in Kingston: 1905–1909

In 1905, Garvey moved to Kingston, the capital city. He found work at the P.A. Benjamin Manufacturing Company's printing section. He quickly moved up and became their first Afro-Jamaican foreman. His mother and sister later joined him in the city. In January 1907, a big earthquake hit Kingston, destroying much of the city. Garvey and his family had to sleep outside for months. His mother died in March 1908. While in Kingston, Garvey became a Catholic.

Garvey became a trade unionist and a leader in the printers' union. He played a key role in a strike in November 1908. The strike failed, and Garvey was fired. He found it hard to get private work after that. These experiences made Garvey angry about the unfairness in Jamaican society.

He joined the National Club, Jamaica's first nationalist group. He helped publish a pamphlet called The Struggling Mass. In early 1910, Garvey started his own magazine, Garvey's Watchman, but it only lasted three issues. He also took speaking lessons and entered public speaking contests.

Travels Abroad: 1910–1914

Many Jamaicans left the island for better jobs. In mid-1910, Garvey went to Costa Rica. He worked as a timekeeper on a large banana farm. He became upset by how the workers were treated. In 1911, he started a newspaper, Nation/La Nación, which criticized the farm company. This caused him trouble with the police.

Garvey then traveled through Central America, working odd jobs in Honduras, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela. In Colón, Panama, he started another newspaper, La Prensa. In 1911, he became very sick and decided to return to Kingston. He then decided to travel to London, England, hoping to continue his education. He sailed to England in the spring of 1912. He visited the House of Commons and Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park, where he began giving speeches.

In early 1913, he worked for the African Times and Orient Review magazine. This magazine supported Ethiopianism and home rule for British-ruled Egypt. Garvey also took evening law classes at Birkbeck College. He then toured parts of Europe.

Back in London, he read in the British Museum library. There, he found Up from Slavery by the African-American leader Booker T. Washington. Washington's book greatly influenced Garvey. Almost out of money, he decided to return to Jamaica. On his way home in June 1914, he met an Afro-Caribbean missionary who had been to Africa. Learning more about colonial Africa, Garvey began to imagine a movement to unite black people worldwide.

Starting the UNIA

Forming the UNIA: 1914–1916

Garvey returned to Jamaica in July 1914. That same month, he launched the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, or UNIA. Its motto was "One Aim. One God. One Destiny." It aimed to create a brotherhood among black people, promote race pride, and help develop Africa. At first, it had few members. Many Jamaicans did not like the use of the word "Negro", but Garvey embraced it.

Garvey became UNIA's president. The group presented itself as a charity, not a political group. It focused on helping the poor and planned to build a training college like Booker T. Washington's Tuskegee Institute. Garvey wrote to Washington, who sent an encouraging reply. UNIA showed loyalty to the British Empire and supported the British effort in World War I.

In August 1914, Garvey met Amy Ashwood, who later joined UNIA. She helped them get a better headquarters. She and Garvey became engaged in secret. In March 1916, Garvey decided to move to the United States.

Moving to the United States: 1916–1918

Garvey arrived in the United States and stayed in Harlem, a mostly black area of New York City. He began giving speeches, hoping to become a public speaker. He went on a speaking tour across 38 states. He visited the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. After six months, he returned to New York City.

In May 1917, Garvey started a New York branch of UNIA. Anyone "of Negro blood and African ancestry" could join for a small monthly fee. He often spoke on 135th Street, reaching out to both Afro-Caribbean migrants and African Americans. He began working with Hubert Harrison, who also promoted black self-reliance.

After the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, Garvey first tried to join the military but was found unfit. He later opposed African-American involvement in the war. After the East St. Louis Race Riots in 1917, where white mobs attacked black people, Garvey called for armed self-defense.

By late 1917, many of Harrison's supporters joined UNIA. Garvey briefly stepped down as president but soon regained control after legal action.

The UNIA Grows: 1918–1921

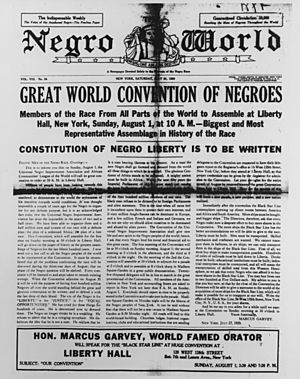

UNIA membership grew quickly in 1918. Garvey planned for UNIA to open businesses like an import-export company, a restaurant, and a laundry. He also wanted to buy a permanent building for the group. In April, Garvey started a weekly newspaper, the Negro World. This paper was his main way of sharing his ideas.

The Negro World was supported by people like Madam C. J. Walker. Garvey refused to advertise skin-lightening or hair-straightening products, telling black people to "take the kinks out of your mind, instead of out of your hair." By the end of its first year, the newspaper's circulation was almost 10,000. Copies were sent to the U.S., Caribbean, Central, and South America. Some British West Indian islands banned the publication.

Amy Ashwood, Garvey's old friend, joined him in New York in October 1918 and became UNIA's General Secretary. After World War I, Garvey joined other black leaders to form the International League for Darker People. They wanted to speak at the Paris Peace Conference to demand respect for people of color, but they could not get travel documents.

In the U.S., many African Americans who had served in the military refused to return to their old roles. There were many racial clashes in 1919. The government worried about revolutionary behavior among African Americans. The Bureau of Investigation, led by J. Edgar Hoover, investigated Garvey. They thought he was politically dangerous and wanted to deport him. However, the Labor Department refused, saying there was not enough proof.

Success and Challenges

UNIA grew very fast, with branches in 25 U.S. states and other countries. Garvey claimed two million members by June 1919, though this was likely an exaggeration. UNIA was smaller than the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), but it reached many more ordinary people and Afro-Caribbean migrants. The NAACP was a multi-racial group that wanted integration, while UNIA only allowed black members.

There were tensions between UNIA and the NAACP. Garvey often criticized the NAACP leader W. E. B. Du Bois. Their relationship became very difficult.

UNIA opened a restaurant, an ice cream parlor, and a hat store. Garvey moved to a new home. UNIA also bought a church building in Harlem, which Garvey named "Liberty Hall," inspired by the Irish independence movement. The dedication ceremony was in July 1919.

Garvey also created the African Legion, a group of uniformed men who marched in UNIA parades. A secret service was formed from Legion members to gather information. In January 1920, Garvey started the Negro Factories Corporation, which opened grocery stores, a restaurant, a laundry, and a publishing house.

A strong admiration for Garvey grew within UNIA. His portraits hung in the headquarters, and recordings of his speeches were sold.

In August 1920, UNIA held the First International Conference of the Negro Peoples in Harlem. About 25,000 people gathered in Madison Square Gardens. At the conference, UNIA delegates declared Garvey the Provisional President of Africa. This meant he would lead a government-in-exile that could take power in Africa when colonial rule ended. Many outside the movement made fun of this title. The conference also created a "Declaration of the Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World," which spoke out against European colonial rule in Africa.

UNIA also built ties with the Liberian government, hoping to get land for African-American settlers. In 1921, Garvey sent a UNIA team to Liberia to check on settlement possibilities.

Personal Life and the Black Star Line

In October 1919, Garvey survived an assassination attempt. He was shot but recovered quickly. Soon after, he proposed to Amy Ashwood, and they had a private Catholic wedding on Christmas Day, followed by a big celebration at Liberty Hall. Their marriage soon faced problems. Ashwood complained about Garvey's closeness with his secretary, Amy Jacques. Garvey was unhappy with Ashwood's behavior. Three months into the marriage, Garvey sought to end it. The court process lasted two years. Garvey then moved in with Amy Jacques.

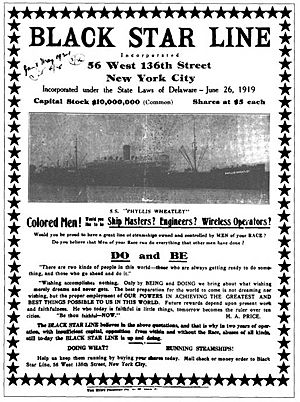

UNIA began selling shares for a new business, the Black Star Line. This shipping company aimed to challenge white control of the sea. Garvey wanted a black-owned and black-staffed shipping line to travel between Africa and the Americas. He hoped to raise $2 million from black donors. Many African Americans were proud to buy stock, seeing it as an investment in their community's future.

By September 1919, the Black Star Line had raised $50,000 and bought a thirty-year-old ship, the SS Yarmouth. The ship was launched on 31 October. However, the company struggled to find enough trained black seamen, so its first chief engineer and chief officer were white.

The Yarmouth's first trip revealed many problems, costing $11,000 in repairs. Its second voyage also faced issues. In early 1922, the Yarmouth was sold for scrap metal for very little money. The Black Star Line faced many financial difficulties and eventually collapsed.

In 1921, Garvey traveled to the Caribbean on a new Black Star Line ship, the Antonio Maceo. In Jamaica, he criticized the local people, which made him many enemies. He then traveled to Costa Rica and Panama. He tried to return to the U.S. but was denied entry several times. He was finally allowed back after writing to the State Department.

Legal Troubles and Imprisonment: 1923–1927

In May 1923, Garvey and three others faced a court case related to the Black Star Line. Garvey chose to represent himself, but he struggled without legal training. After more than a month, the jury found Garvey guilty, but his co-defendants not guilty.

Many of Garvey's supporters protested his conviction, calling it unfair. With Garvey in prison, UNIA's membership began to drop. From jail, Garvey continued to write, blaming the NAACP for his conviction.

Out on Bail: 1923–1925

In September, Garvey was granted bail for $15,000, which UNIA raised. Free again, he toured the U.S., giving speeches. He continued to emphasize the need for racial separation and migration to Africa. He even defended his meetings with the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), saying they were more "honest" than the NAACP.

In February 1924, UNIA proposed bringing 3,000 African-American migrants to Liberia. Liberia's President, Charles D. B. King, seemed to agree. However, when a UNIA team arrived in Liberia, they were arrested and deported. Liberia's government then said it would not allow any Americans to settle there. Garvey blamed Du Bois for this change, but later evidence suggested Liberia never truly intended to allow the settlement.

UNIA faced more problems. The Negro World started advertising skin-lightening products again to raise money. The Black Star Line bought a new ship, the SS General G W Goethals, and renamed it the SS Booker T. Washington.

Imprisonment and Release: 1925–1927

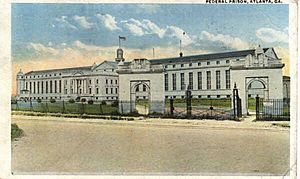

In early 1925, a court upheld Garvey's conviction. He was arrested and sent to the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. In prison, he did cleaning tasks and sometimes got sick. He received letters from UNIA members and his wife, Amy Jacques, who visited him often. With his support, she published a book of his speeches, Philosophy and Opinions.

While Garvey was in prison, Amy Ashwood tried to challenge his divorce from her, which would have made his marriage to Amy Jacques invalid. However, the court ruled in Garvey's favor. UNIA faced more financial problems, and Liberty Hall was eventually sold.

A petition with 70,000 signatures asked for Garvey's release. President Calvin Coolidge agreed to end his sentence early, on 18 November 1927. However, Garvey was to be deported immediately after his release. He was taken by train to New Orleans and then by ship to Jamaica.

Later Years

Return to Jamaica: 1927–1935

In Kingston, Garvey was welcomed by his supporters. UNIA members raised money to help him settle. He bought a large house, which he called "Somali Court." His wife and belongings soon joined him. He continued giving speeches in Jamaica, urging Afro-Jamaicans to improve their lives and stand against other immigrant groups.

Garvey tried to travel through Central America, but his requests were denied. He traveled to England in April 1928, renting a house in London. In May, he spoke at the Royal Albert Hall. He and his wife also visited Paris and Switzerland, then Canada, where he was briefly detained.

Back in Kingston, UNIA acquired Edelweiss Park, which became its new headquarters. They held a conference there, with a large parade through the city. UNIA also put on plays at Edelweiss Park, including one written by Garvey. In September 1930, his first son, Marcus Garvey III, was born. Three years later, his second son, Julius, was born.

In Kingston, Garvey was elected a city councilor. He started Jamaica's first political party, the People's Political Party (PPP), to run in elections. In September 1929, he launched the PPP's plan, which included land reform, a minimum wage, and building Jamaica's first university. One policy led to him being charged with disrespecting the justice system. He was found guilty and sentenced to three months in prison.

While in prison, other councilors removed him from the Kingston council. Garvey was angry and wrote an article against them, which led to another charge. He was convicted but later won an appeal. He then ran for legislative assembly but lost.

During the Great Depression, Garvey faced increasing money problems. He worked as an auctioneer and used his wife's savings. In 1934, Edelweiss Park was sold. Unhappy in Jamaica, Garvey decided to move to London, sailing there in March 1935. He told a friend that he had left Jamaica "broken in spirit, broken in health and broken in pocket."

Life in London: 1935–1940

In London, Garvey tried to rebuild UNIA. He opened a new headquarters and launched a monthly journal, Black Man. He returned to speaking at Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park. He also hoped to become a Member of Parliament, but this did not happen.

In 1935, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War began as Italy invaded Ethiopia. Garvey spoke out against Italy and praised Ethiopia's leader, Haile Selassie. However, he later became critical of Selassie, blaming him for Ethiopia's failures. When Selassie fled to Britain, Garvey tried to meet him but was refused. Garvey then became more openly hostile to Selassie, which distanced him from other black activists who supported Selassie.

In June 1937, Garvey's wife and children came to England. Garvey then went on a speaking tour of Canada and the Caribbean. In Trinidad, he criticized an oil workers' strike, which caused tension with other black leaders in London. Back in London, Garvey moved to a new family home. He often debated with other activists. In the summer of 1938, he returned to Toronto for another UNIA conference.

While Garvey was away, his wife and sons returned to Jamaica. Doctors had recommended a warmer climate for his son's severe rheumatism. Garvey was very angry when he returned to London and found they had left without telling him. Garvey became more isolated, and UNIA ran out of money as its international membership decreased. He met his first wife, Amy Ashwood, who was also living in London.

Death and Burial: 1940

In January 1940, Garvey had a stroke that left him largely paralyzed. His secretary, Daisy Whyte, cared for him. Rumors of his death spread, and many newspapers published obituaries, which he read. Garvey then had a second stroke and died on 10 June 1940, at age 52. His body was buried in a vault in the catacombs of St Mary's Catholic Cemetery in Kensal Green, London.

Many memorials were held for Garvey, especially in New York City and Kingston. Some of his followers refused to believe he had died, thinking it was a conspiracy. Both Amy Ashwood and Amy Jacques claimed to be his true widow.

Years later, in Jamaica, a strong admiration for Garvey grew. By the 1950s, Jamaican politicians often spoke his name. In 1964, Garvey's remains were brought back to Jamaica. His body lay in state at Holy Trinity Cathedral in Kingston, and thousands came to see it. He was reburied in King George VI Memorial Park on 22 November 1964, with a grand ceremony. A monument, designed by G. C. Hodges, marks his tomb, which is shaped like a black star. A bust of Garvey, created by Alvin T. Marriot, stands behind it.

Garvey's Ideas

Race and Racial Separation

"Race first" was a common saying in Garveyism. Garvey believed that "no race in the world is so just as to give others, for the asking, a square deal." He thought each race would always put its own interests first. He rejected the idea that different races would simply blend together in America. He believed that white Americans would never truly treat black Americans as equals.

Garvey's belief in racial separation and his support for black people moving to Africa made him popular with groups like the KKK. The KKK also wanted racial separation. Garvey was willing to work with the KKK to achieve his goals. He said they were "better friends" to black people than other white groups because they were honest about their intentions.

Pan-Africanism

Garvey was a Pan-Africanist, meaning he believed in the unity of all African people. He called for "a United Africa for the Africans of the World." The UNIA promoted the idea that Africa was the natural home for black people living outside the continent. While in prison, he wrote "African Fundamentalism," calling for "the founding of a racial empire whose only natural, spiritual and political aims shall be God and Africa, at home and abroad."

Garvey supported the Back-to-Africa movement. He believed that a skilled group of African Americans should go to West Africa first. They would build railroads and schools, and then other black people could join them. He knew most African Americans would not move to Africa until it had modern comforts. His plans to move African Americans to Liberia did not succeed.

In the 1920s, Garvey spoke of wanting a "big black republic" in Africa. He imagined Africa as a one-party state where the president would have "absolute authority." He even told a historian that he and his followers were "the first fascists," saying that Mussolini copied Fascism from him.

Garvey never visited Africa himself and did not speak any African languages. He knew little about the continent's many cultures. His critics often said his views of Africa were based on dreams, not reality. He believed Africa was "backward" and needed the help of Western, Christian states. He wanted to "assist in civilizing the backward tribes of Africa."

Economic Views

Garvey believed black people needed to be financially independent. Through UNIA, he tried to achieve this by starting businesses like the Black Star Line and the Negro Factories Corporation. He said, "without commerce and industry, a people perish economically." He believed black people needed their own businesses to be safe from discrimination.

Economically, Garvey supported capitalism. He believed it was "necessary to the progress of the world." In the U.S., he promoted a capitalist approach for black communities. He admired Booker T. Washington's economic efforts but thought businesses should involve group decision-making and profit-sharing. He believed there should be limits on how much wealth individuals or companies could control. He imagined a global network of black people trading with each other, with the Black Star Line helping this goal.

Garvey was not a socialist. He strongly opposed efforts by socialist and communist groups to get African Americans to join trade unions. He believed the communist movement did not serve the interests of black people because it was created by white people. He said communism was "a dangerous theory" because it would put government in the hands of "an ignorant white mass who have not been able to destroy their natural prejudices towards Negroes."

Black Christianity

Garvey's movement had a strong religious side. He imagined a form of Christianity specifically for black African people, similar to Catholicism. He attended the founding ceremony of the African Orthodox Church in Chicago in 1921.

Garvey believed black people should worship a God who was also depicted as black. He said, "If the white man has the idea of a white God, let him worship his God as he desires. Since the white people have seen their God through white spectacles, we have only now started out to see our God through our own spectacles... we shall worship Him through the spectacles of Ethiopia." He wanted black people to see images of Jesus of Nazareth and the Virgin Mary as black Africans.

Personality and Family

Garvey was short and stocky. He suffered from asthma and lung infections. He was a "restless young man" with a "naïve but determined personality." He was very focused on his goals.

He was an excellent speaker. His speeches were a mix of passionate preaching and formal English, with a Caribbean rhythm. Garvey enjoyed debating and wanted to be seen as a learned man. He read many books, especially on history. He often used fancy titles and clothes, which some people criticized as showing off. Even his enemies agreed he was a skilled organizer and promoter.

Garvey was a "man of grand, purposeful gestures." He was also described as "ascetic" with "conservative tastes." He collected antique ceramics. He valued courtesy and respect.

Garvey loved dressing in military uniforms and enjoyed grand ceremonies. He believed these displays would inspire black people. Some critics found this silly.

Garvey was a Catholic. In 1919, he married Amy Ashwood in a Catholic ceremony, but they separated after three months. He later obtained a divorce. His first son, Marcus Garvey III (1930–2020), became an electrical engineer. His second son, Julius Garvey (born 1933), became a vascular surgeon.

See also

In Spanish: Marcus Garvey para niños

In Spanish: Marcus Garvey para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |