Up from Slavery facts for kids

Up from Slavery is an autobiography written in 1901 by Booker T. Washington (1856–1915). This book tells the story of his life, from being enslaved as a child during the Civil War to becoming a famous educator. It shares how he overcame many challenges to get an education at the Hampton Institute.

Washington also writes about his work starting schools like the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. These schools helped Black people and other groups learn useful skills. His goal was to help them improve their lives and communities. He believed in combining school subjects with learning a trade, like building or farming. Washington felt this approach would also show white communities the value of educating Black people.

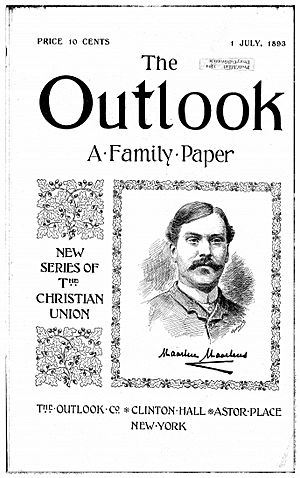

The book first appeared in parts in 1900 in The Outlook, a Christian newspaper. This allowed Washington to get feedback from readers as he wrote.

Booker T. Washington was a well-known figure, but some people, like W. E. B. Du Bois, disagreed with some of his ideas. Up from Slavery became a best-seller. It was the most popular autobiography by an African American until Malcolm X's book. In 1998, the Modern Library called it one of the top 100 nonfiction books of the 20th century.

Contents

- What the Book is About

- A Look at the Chapters

- Chapter 1: A Slave Among Slaves

- Chapter 2: Boyhood Days

- Chapter 3: The Struggle for Education

- Chapter 4: Helping Others

- Chapter 5: The Reconstruction Period

- Chapter 6: Black Race and Red Race

- Chapter 7: Early Days at Tuskegee

- Chapter 8: Teaching School in a Stable and a Hen-house

- Chapter 9: Anxious Days and Sleepless Nights

- Chapter 10: A Harder Task Than Making Bricks Without Straw

- Chapter 12: Raising Money

- Chapter 13: Two Thousand Miles for a Five-Minute Speech

- Chapter 14: The Atlanta Exposition Address

- Chapter 15: The Secret Success in Public Speaking

- Chapter 16: Europe

- Chapter 17: Last Words

- Historical Background

- Washington and His Critics

- In Popular Culture

What the Book is About

Up from Slavery covers over 40 years of Booker T. Washington's life. It shows his journey from being enslaved to becoming a school leader and a key voice in race relations in the South. In the book, Washington explains how he moved up in society. He did this through hard work, getting a good education, and building relationships with important people.

He often highlights how important education is for Black people. He believed this was a good way to improve relationships between races in the South, especially after the Reconstruction Era. The book shares Washington's calm and non-confrontational message, using his own life as an example.

Main Ideas in the Book

- The power of education.

- Learning to be independent.

- The value of hard work.

- Being humble.

- How people can change and grow.

- Dealing with poverty among Black communities.

A Look at the Chapters

The book tells Washington's story chapter by chapter. Here are some of the key parts:

Chapter 1: A Slave Among Slaves

This chapter gives a quick look at what life was like for enslaved people. Washington shares his own experiences of hardship before freedom. He describes his living conditions and how his mother worked very hard.

Chapter 2: Boyhood Days

Here, readers learn how important it was for newly freed people to choose their own names. It also shows how much they wanted to reunite their families. After finding family and choosing names, they often looked for jobs, sometimes far from their former enslavers. Washington explains how he got his full name: Booker Taliaferro Washington. This chapter also talks about the tough work children did in the mines. Booker loved learning and tried to balance his long work hours with school.

Chapter 3: The Struggle for Education

In this chapter, Washington works hard to earn money. He needs it to travel to and stay at the Hampton Institute. This was his first time truly understanding the importance of being willing to do manual labor. He also introduces General Samuel C. Armstrong, who played a big role in his life.

Chapter 4: Helping Others

Washington describes what life was like at Hampton Institute. He talks about his first trip home from school. He even returned early from vacation to help teachers clean their classrooms. The next summer, he was chosen to teach local students, both young and old. He taught them through a night school, Sunday school, and private lessons. This chapter also mentions groups like the Ku Klux Klan for the first time.

Chapter 5: The Reconstruction Period

Washington describes the South during the Reconstruction Era. He shares his thoughts on projects from that time, like education, job training, and voting rights. He felt that the Reconstruction policy was built on a "false foundation." He wanted to help build a stronger foundation based on using "the hand, head, and heart."

Chapter 6: Black Race and Red Race

General Armstrong asked Washington to return to Hampton Institute. His job was to teach and advise a group of young Native American men. Washington discusses different examples of racism against both Native Americans and African Americans. He also started a night school during this time.

Chapter 7: Early Days at Tuskegee

General Armstrong again helped Washington with his next big project. This was to start a school for African Americans in Tuskegee, Alabama. Washington describes the conditions in Tuskegee and how hard he worked to build the school. He felt it was "much like making bricks without straw," meaning it was very difficult without resources. He also describes a typical day for an African American living in the countryside at that time.

In May 1881, General Armstrong told Washington about a request from Alabama. They needed someone to lead a "colored school" in Tuskegee. The person writing the letter thought only a white man could do the job. But General Armstrong recommended Washington, and he got the position.

Washington arrived in Tuskegee, a town of 2,000 people. It was in the "Black Belt" of the South, where many residents were Black. He explains that the term "Black Belt" likely came from the rich, dark soil in the area. This was also where enslaved people were most profitable.

His first job was to find a place for the school. He found a run-down "shanty" and an African-American Methodist church. He also traveled around the area to meet local people. He describes families working in cotton fields. He saw that most farmers were in debt. Schools were often in churches or log cabins with few supplies. Some had no heat in winter, and one school had only one book for five children.

He tells the story of a 60-year-old man who was sold in 1845. The man said, "There were five of us; myself and brother and three mules." Washington shares these stories to show how much things later improved.

Chapter 8: Teaching School in a Stable and a Hen-house

Washington explains why a new kind of education was needed for Tuskegee's children. A typical New England education would not be enough to help them improve their lives. This chapter introduces important partners: George W. Campbell, Lewis Adams, and his future wife, Olivia A. Davidson. They all agreed that just learning from books was not enough. The goal for Tuskegee students was to become good teachers, farmers, and moral people.

Washington describes his first days at Tuskegee and his teaching style. He took a complete approach, researching the area and its people. He saw how poor many were. His visits showed that education was valued but lacked funding. This justified setting up the new school.

Tuskegee was a rural area where farming was the main job. So, the school became an industrial school. It taught students skills useful for their local area. He faced challenges starting the school, which opened on July 4, 1881. Some white people opposed it. They questioned the value of educating African Americans. "These people feared the result of education would be that the Negros would leave the farms, and that it would be difficult to secure them for domestic service."

He relied on advice from two men who wrote to General Armstrong asking for a teacher. One was a white man and former slave owner, George W. Campbell. The other was a Black man and former enslaved person, Lewis Adams.

When the school opened, they had 30 students, about half boys and half girls. Many more wanted to come, but students had to be over 15 and have some education already. Many were public school teachers, and some were around 40 years old. The number of students grew each week, reaching nearly 50 by the end of the first month.

A co-teacher, Olivia A. Davidson, joined after six weeks. She later became his wife. She had studied in Ohio and came South because she heard teachers were needed. She was brave, caring for the sick when others would not, like a boy with smallpox. She also trained at Hampton and then at Massachusetts State Normal School.

She and Washington agreed that students needed more than just "book education." They believed they must show students how to care for their bodies and earn a living after school. They tried to educate them so they would want to stay in farming areas. Many students initially came to study so they would not have to work with their hands. But Washington wanted them to be able to do all kinds of work and not be ashamed of it.

Chapter 9: Anxious Days and Sleepless Nights

This chapter talks about the institute's relationship with the people of Tuskegee. It also covers buying and farming new land, building a new building, and getting help from generous donors, mostly from the North. Washington's first wife, Fannie N. Smith, passed away in this chapter. He had a daughter named Portia.

Chapter 10: A Harder Task Than Making Bricks Without Straw

Washington explains why it was important for students to build their own school buildings. He says, "Not a few times, when a new student has been led into the temptation of marring the looks of some building by lead pencil marks or by the cuts of a jack-knife, I have heard an old student remind him: 'Don't do that. That is our building. I helped put it up.'" The title refers to the difficulty of making bricks without the right tools, like money and experience. Through hard work, the students made good bricks. This success gave them confidence for other projects, like building vehicles.

Chapter 12: Raising Money

Washington traveled North to get more money for the institute. He was very successful. After meeting one man, the Institute received $10,000. From another couple, they received $50,000. Washington felt a lot of pressure for his school and students to succeed. He knew that failure would make his race look bad. Around this time, Washington began working with Andrew Carnegie, convincing Carnegie that the school deserved support. Washington found that both large donations and small loans were helpful. Small loans paid bills and showed the community's trust in this type of education.

Chapter 13: Two Thousand Miles for a Five-Minute Speech

Washington married again, this time to Olivia A. Davidson, who was first mentioned in Chapter 8. This chapter marks the start of Washington's public speaking career. His first big speech was at the National Education Association. His next goal was to speak to a white audience in the South. His first chance was short, giving him only five minutes to speak. Later speeches had clear goals: in the North, he sought funds; in the South, he encouraged "the material and intellectual growth of both races." One important speech led to the Atlanta Exposition Speech.

Chapter 14: The Atlanta Exposition Address

This chapter includes the full speech Washington gave at the Atlanta Exposition. He also explains how people reacted to it. At first, everyone was happy. Then, some African Americans felt Washington had not been strong enough about their rights. Over time, however, the African-American public generally became pleased again with Washington's goals for improving their lives.

Washington also talks about African-American religious leaders. He makes a statement about voting that caused much debate: "I believe it is the duty of the Negro – as the greater part of the race is already doing – to deport himself modestly in regard to political claims, depending upon the slow but sure influences that proceed from the possession of property, intelligence, and high character for the full recognition of his political rights." He believed full voting rights would come slowly, not overnight. He did not think Black people should stop voting. But he felt their votes should be more influenced by intelligent and good neighbors. He also believed no state should allow an uneducated white man to vote while preventing a Black man in the same situation from voting. He said such a law was unfair and would eventually backfire.

Chapter 15: The Secret Success in Public Speaking

Washington again discusses how his Atlanta Exposition Speech was received. He then gives advice on public speaking and describes several memorable speeches he gave.

Chapter 16: Europe

The author married for a third time, to Margaret James Murray. He talks about his children. He and his wife were offered a chance to travel to Europe. Washington had always dreamed of this trip, but he worried about how people would react. He had seen many successful Black individuals turn away from their communities. Mr. and Mrs. Washington enjoyed their trip. They especially liked seeing their friend, Henry Ossawa Tanner, an African-American artist, being praised by everyone. While abroad, they also had tea with Queen Victoria and Susan B. Anthony. When they returned to the United States, Washington was asked to visit Charleston, West Virginia, near his old home.

Chapter 17: Last Words

Washington describes his final talks with General Armstrong and his first with Armstrong's replacement, Rev. Dr. Hollis B. Frissell. The biggest surprise of his life was being invited to receive an honorary degree from Harvard University. He was the first African American to receive this honor. Another great honor for Washington and Tuskegee was a visit from President William McKinley. McKinley hoped this visit would show citizens his "interest and faith in the race." Washington then describes the conditions at Tuskegee Institute and his strong hope for the future of his race.

Historical Background

The late 1800s in America were a time when many white people were hostile towards African Americans. There was a false belief that African Americans could not have survived without slavery. Popular culture often showed negative ideas about Black people, like the characters Jim_Crow_(character) and Zip Coon. When Washington started writing and speaking, he was fighting the idea that African Americans were naturally unintelligent and unable to live in a civilized society.

Washington's main goal was to show audiences that progress was possible. Living in the "Black Belt," he was also at risk of mob violence. So, he was always careful not to anger these groups. When violence happened, he tried to calm his talk of equality to avoid making things worse.

Lynching was common in the South during this time. White mobs would take the law into their own hands, torturing and murdering many Black and even some white people. Victims were attacked for reasons like winning a fight against a white man, protecting someone from a mob, stealing small amounts of money, or showing sympathy for a victim. It was clear that any white person who showed support for Black victims could also become a target. In 1901, a reverend named Quincy Ewing called on the press and churches to unite against lynching. Lynching continued for many decades.

Some people criticized Washington's calm message, thinking he didn't truly want Black people to rise up. Others, considering the dangerous times he lived in, supported him for speaking out at all.

Washington and His Critics

Since it was published, Up From Slavery has been seen in different ways. Some view Booker T. Washington as someone who gave in to white demands. Others see him as a smart leader trying to find a way for Black people to succeed during a very difficult time. While today's civil rights movements often use more direct methods, Washington was a very important figure in his era.

Most criticisms of him focus on his "accommodationism," meaning his willingness to compromise. However, in his private life, he often secretly funded efforts to fight against racial injustice. His Atlanta Exposition speech shows his complex nature. He tried to say things that everyone present could agree with, no matter their true intentions. Historian Fitzhugh Brundage praises Washington for "seeking to be all things to all men in a multifaceted society." Many historians disagree about whether he should be called an "accommodationist." For example, Robert Norrell wrote that Washington "worked too hard to resist and to overcome white supremacy to call him an accommodationist."

W. E. B. DuBois at first praised Washington's ideas for Black progress. He even said Washington's Atlanta Exposition speech could be a "real basis for the settlement between whites and blacks in the South." In his book The Souls of Black Folk, DuBois congratulated Washington for gaining the trust of white Southerners through cooperation. He also understood the unstable situation in the South and the need to be sensitive to community feelings. However, DuBois believed Washington failed to be sensitive to African Americans. DuBois argued that many educated and successful African Americans would criticize Washington's work, but they were being silenced. This is where their paths separated: Washington with his "Tuskegee Machine" and DuBois with the "Niagara Movement."

In 1905, the Niagara Movement released a statement demanding civil rights and opposing oppression. This Movement was different from Washington's approach. It took a more radical path: "Through helplessness we may submit, but the voice of protest of ten million Americans must never cease to assail the ears of their fellows, so long as America is unjust." For a while, the Movement grew successfully. But it lost its power when its different chapters started to disagree. Eventually, the Movement's efforts helped create the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Other people also joined this discussion about the future of African Americans. One was W. H. Thomas, another Black man. Thomas believed African Americans were "deplorably bad" and that it would take a "miracle" for them to make any progress. Like Washington and DuBois, Washington and Thomas had some areas of agreement. For example, they both thought the best chance for an African American was in farming and country life.

Similarly, Thomas Dixon, Jr., author of The Clansman (1905), started a newspaper debate with Washington about his industrial education system. Dixon likely did this to promote his upcoming book. He said that the new independence of Tuskegee graduates would cause competition. He wrote, "Competition is war…. What will the [southern white man] do when put to the test? He will do exactly what his white neighbor in the North does when the Negro threatens his bread—kill him!"

In Popular Culture

In September 2011, a seven-part TV series and DVD set called Up From Slavery was made. This series, directed by Kevin Hershberger, is not directly about Booker T. Washington's book. Instead, it tells the story of Black slavery in America. It covers from the first arrival of African slaves in Jamestown in 1619 to the Civil War. It also covers the 15th Amendment in 1870, which gave all citizens the right to vote regardless of race or past slavery. This amendment was one of the Reconstruction Amendments that finally ended legal slavery in the United States.

|

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |