Hubert Harrison facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hubert Harrison

|

|

|---|---|

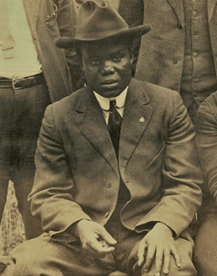

Harrison in 1913

|

|

| Born |

Hubert Henry Harrison

April 27, 1883 Estate Concordia, St. Croix, Danish West Indies (now U.S. Virgin Islands)

|

| Died | December 17, 1927 (aged 44) New York City, New York, USA

|

| Spouse(s) | Irene Louise Horton (m. 1909-1927; his death) |

| Children | Frances Marion (b. 1910), Alice (b. 1911), Aida Mae (b. 1912), Ilva Henrietta (b. 1914), and William (b. 1920) |

| Parent(s) | Ceclia Elizabeth Haines and Adolphus Harrison |

Hubert Henry Harrison (born April 27, 1883 – died December 17, 1927) was an important writer, speaker, and activist. He lived in Harlem, New York and worked for fairness for all people. People called him "the father of Harlem radicalism" and "the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time." He was also known as "The Black Socrates" because of his deep thinking.

Harrison moved from St. Croix to the United States when he was 17. He played a big part in major movements for equality. He was a leading Black organizer in the Socialist Party of America from 1912 to 1914. In 1917, he started the Liberty League and a newspaper called The Voice. These were the first of their kind for the "New Negro" movement, which focused on Black pride and rights. His work helped inspire leaders like Marcus Garvey.

Harrison was a very influential thinker. He encouraged workers to understand their shared interests (class consciousness). He also promoted black pride, agnostic atheism (not believing in God), and secular humanism (focusing on human values). He believed in social progress and free thinking. He was a "radical internationalist," meaning he cared about fairness for people all over the world. Many "New Negro" activists, including A. Philip Randolph and Marcus Garvey, were influenced by him.

Contents

Early Life in St. Croix

Hubert Harrison was born in 1883 on Estate Concordia in St. Croix, which was then part of the Danish West Indies. His mother was Cecilia Elizabeth Haines. His biological father, Adolphus Harrison, had been enslaved.

Hubert grew up experiencing poverty. But he also learned about African customs and the history of his people in St. Croix. They had a strong tradition of fighting for their rights. One of his school friends was D. Hamilton Jackson, who later became a labor leader.

Later in life, Harrison worked with many activists from the Virgin Islands. He was especially active after the U.S. bought the islands in 1917. He spoke out against unfair treatment under U.S. naval rule.

Moving to New York

In 1900, at age 17, Harrison moved to New York City. He was an orphan and joined his older sister there. In New York, he faced a type of racial unfairness he had not known before. The United States had a very strict "color line" that separated people by race.

When he first arrived, Harrison worked low-paying jobs. He also went to high school at night. He continued to learn on his own throughout his life, becoming a self-taught scholar. Even in high school, people noticed how smart he was. A New York newspaper called The World described him as a "genius." In 1903, at age 20, The New York Times published one of his letters. He became an American citizen and lived in the U.S. for the rest of his life.

Family Life

In 1909, Hubert Harrison married Irene Louise Horton. They had five children together: four daughters and one son.

His Ideas and Beliefs

In his early years in New York, Harrison started writing letters to The New York Times. He wrote about important topics like lynching, Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, and books. He also gave talks on subjects like poetry and the Reconstruction era.

Harrison became interested in the freethought movement. This movement encouraged using science, facts, and reason to solve problems. It was different from relying on religious beliefs. He stopped being a Christian and became an agnostic atheist. This meant he didn't believe in God and thought humans should be at the center of their own lives.

Harrison strongly disagreed with traditional religion. He called the Bible a "slave master’s book." He believed that people who were deeply religious were often too accepting of unfairness. He famously said, "Show me a population that is deeply religious, and I will show you a servile population, content with whips and chains." He also supported the separation of church and state and teaching evolution in schools.

In 1907, Harrison got a job at the Post Office.

He supported the protest ideas of leaders like W. E. B. Du Bois. After the Brownsville Affair, he openly criticized Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. He also criticized the Republican Party.

Harrison also disagreed with Booker T. Washington, another important Black leader. Harrison felt Washington's ideas were too submissive. In 1910, Harrison wrote letters criticizing Washington. Because of this, he lost his job at the Post Office.

Working for Change

In 1911, after losing his job, Harrison began working full-time for the Socialist Party of America. He became a leading Black Socialist in America. He spoke out against capitalism and campaigned for presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs in 1912. He also started the Colored Socialist Club to reach African Americans.

Harrison wrote articles explaining how racism was connected to economic competition. He argued that rich capitalists used racism to keep workers divided. He believed Socialists should especially help African Americans. He said that the treatment of Black people showed if a democracy was truly fair.

Harrison also supported the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). This group worked for workers' rights across different races. He spoke at the important Paterson Silk Strike of 1913. He believed in direct action to make changes.

However, the Socialist Party had its own problems with racism. Some local groups were segregated. Harrison felt that white Socialist leaders put "Race first and class after." He resigned from the Socialist Party in 1918.

Leading the New Negro Movement

After leaving the Socialist Party, Harrison focused on free thought and education. He gave many outdoor talks in Harlem. These talks helped create a tradition of powerful public speaking in Harlem. He inspired later speakers like Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X.

In 1915, Harrison decided to focus his work on Harlem's Black community. He wrote about Black theater and how it helped express the feelings of African Americans.

Harrison created the "New Negro Movement." This movement focused on "race first" – meaning Black people should unite and fight for their rights. It was a movement for equality, justice, and economic power. This movement helped set the stage for Marcus Garvey's movement. It also encouraged interest in Black literature and arts.

In 1917, during World War I, African Americans were asked to fight for democracy. But at home, they still faced lynching, segregation, and discrimination. Harrison started the Liberty League and the Voice: A Newspaper for the New Negro. These were meant to be a more radical option than the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The Liberty League wanted to reach ordinary Black people, not just the educated elite. It promoted internationalism, political independence, and awareness of race and class issues. It called for full equality, laws against lynching, and support for anti-imperialist causes. It also encouraged armed self-defense. The Voice newspaper reached up to 10,000 readers. However, it stopped publishing after five months because Harrison refused ads for products like hair straighteners that he felt hurt Black pride.

In 1918, Harrison helped lead the Negro-American Liberty Congress. This group protested discrimination during the war. They asked the U.S. Congress for a federal anti-lynching law. Harrison believed that the idea of "democracy" during the war was just a cover for powerful countries' selfish goals.

In 1919, Harrison edited the New Negro magazine. It focused on the international awareness of Black people. He wrote many articles against imperialism and for international cooperation. He understood what was happening in places like India, China, and Africa. He supported armed self-defense for African Americans. But he also praised the non-violent efforts of Mahatma Gandhi.

Working with Marcus Garvey

In January 1920, Harrison became the main editor of the Negro World newspaper. This was the newspaper for Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). For eight months, he made it a leading newspaper for Black radical ideas and literature.

However, Harrison became critical of Garvey. He felt Garvey exaggerated things and focused too much on financial plans. Harrison believed that the main fight for African Americans was in the United States, not in Africa. Even though he continued to write for the Negro World until 1922, he started looking for other political paths.

Later Years and Legacy

In the 1920s, after working with Garvey, Harrison continued to speak, write, and organize. He gave talks on history, science, literature, and international affairs for the New York City Board of Education. He was one of the first people to use radio to discuss his ideas. His writings appeared in many major newspapers and magazines. He openly criticized the Ku Klux Klan and the racist attacks of the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921.

In 1924, Harrison started the International Colored Unity League (ICUL). This group encouraged Black people to develop "race consciousness." This meant being aware of racial unfairness and uniting to respond as a group. The ICUL wanted political rights, economic power, and social justice. It called for Black people to be self-reliant and work together. It also suggested creating a "Negro state" within the U.S. (not in Africa). In 1927, Harrison edited the ICUL's Voice of the Negro until he died.

In his last public talk, Harrison told his audience he needed surgery for appendicitis. He planned to give another lecture afterward. Sadly, he died during the operation at age 44.

His Impact and Work

Hubert Harrison reached out to both large groups of people and individuals. He used newspapers, popular lectures, and street talks to share his ideas. This was different from other leaders who relied on wealthy supporters or focused only on educated Black people. Harrison's approach was aimed directly at the masses. His radical ideas, which combined class and race awareness, have become more studied over time.

For many years after his death in 1927, Harrison was not well-known. But recently, scholars have shown new interest in his life. Columbia University Library has collected his papers and plans to make his writings available online.

Historians say Harrison was "the most class conscious of the race radicals and the most race conscious of the class radicals." This means he deeply understood both economic fairness and racial equality. He helped connect two major parts of the African-American struggle: the labor/civil rights movement and the race/nationalist movement.

Harrison was an amazing speaker and writer. He was reportedly the first Black person to regularly publish book reviews. Many writers and activists, both Black and white, praised his work. He helped Black writers and artists like Claude McKay and Augusta Savage. He was also a pioneer in the freethought movement and encouraged people to read and use libraries. He created "Poetry for the People" sections in various publications.

You can find some of his writings and poetry in a book called A Hubert Harrison Reader (2001). His collected writings are at Columbia University's Rare Book and Manuscript Library. He also wrote two books: The Negro and the Nation (1917) and When Africa Awakes.

In 2005, Columbia University got Harrison's papers. In 2020, these papers were made available online through Columbia's Digital Library.

Writings by Hubert H. Harrison

- A Hubert Harrison Reader, edited by Jeffrey B. Perry (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001).

- "Hubert H. Harrison Papers, 1893-1927: Finding Aid," Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University.

- Harrison, Hubert H., The Negro and Nation (New York: Cosmo-Advocate Publishing Company, 1917).

- Harrison, Hubert H., When Africa Awakes: The "Inside Story" of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World (New York: Porro Press, 1920), New Expanded Edition, edited with notes and a new introduction by Jeffrey B. Perry (New York: Diasporic Africa Press, 2015).

See also

In Spanish: Hubert Harrison para niños

In Spanish: Hubert Harrison para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |