Brownsville affair facts for kids

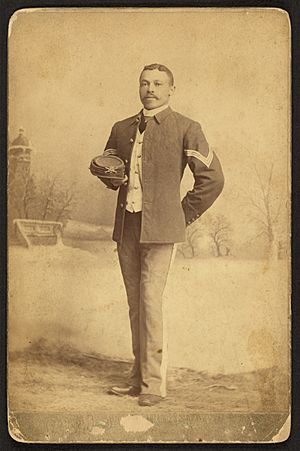

Fort Brown, where the 25th Infantry were stationed at the time of the Brownsville affair

|

|

| Date | August 1906 |

|---|---|

| Location | Brownsville, Texas, United States |

| Also known as | Brownsville raid, Affray at Brownsville |

| Deaths | 1 |

The Brownsville affair was a sad event of racial discrimination that happened in 1906. It took place in Brownsville, Texas, in the southwestern United States. White residents of Brownsville disliked the Buffalo Soldiers, who were black soldiers from a separate army unit. These soldiers were stationed at nearby Fort Brown.

One night, a white bartender was killed and a white police officer was hurt by gunshots. The people of Brownsville immediately blamed the black soldiers of the 25th Infantry Regiment. Even though the soldiers' commanders said they were all in their barracks, some people claimed evidence was planted against the soldiers.

Because of this, President Theodore Roosevelt ordered 167 soldiers from the 25th Infantry Regiment to be discharged without honor. This meant they lost their pensions and could not get federal jobs. Many people, both black and white, were very upset by this decision. After more investigations, some of the men were allowed to join the army again.

In the early 1970s, a new military investigation cleared the names of the black troops. The government officially pardoned them in 1972. Their records were changed to show they had received honorable discharges. However, they did not get money for the time they lost. Only one soldier was still alive then. Congress passed a law to give him a special pension. The other soldiers who had been expelled all received honorable discharges after they had passed away.

Contents

Life for Black Soldiers in 1906

The black US soldiers arrived at Fort Brown on July 28, 1906. They had to follow strict rules about race from the white citizens of Brownsville. This included state laws that kept black and white people separate. These were called Jim Crow laws. They also had to show respect to white people and follow local rules.

The Night of the Incident

A reported attack on a white woman on August 12 made many townspeople angry. To prevent trouble, Major Charles W. Penrose set an early curfew for the soldiers the next night.

On the night of August 13, 1906, a bartender named Frank Natus was killed. Police lieutenant M. Y. Dominguez was also shot and wounded. Right away, people in Brownsville blamed the black soldiers of the 25th Infantry at Fort Brown. But the white commanders at Fort Brown said all the soldiers were in their barracks. Still, local white people, including the mayor, insisted that some black soldiers were involved in the shooting.

The Evidence Against the Soldiers

People in Brownsville started to provide "evidence" against the 25th Infantry. They showed spent bullet cartridges from Army rifles. They claimed these belonged to the 25th's soldiers.

However, other evidence showed that these shells were likely planted. This was done to frame the men of the 25th Infantry. Despite this, investigators accepted the stories from the local white people and the mayor.

What Happened Next

The soldiers of the 25th Infantry were pressured to say who fired the shots. But they insisted they did not know who did it. Captain Bill McDonald of the Texas Rangers investigated 12 soldiers. He tried to connect them to the shooting.

The local court did not find enough evidence to charge anyone. But residents kept complaining about the black soldiers. President Theodore Roosevelt then ordered 167 black troops to be dishonorably discharged. He called it a "conspiracy of silence" because they would not name anyone.

None of these soldiers had received the Medal of Honor, as some stories claimed. Later, 14 of the men were allowed to rejoin the army. But the dishonorable discharge stopped the other 153 men from ever working in the military or for the government again. Some of these black soldiers had served in the U.S. Army for over 20 years. Many were close to retirement and lost their pensions.

A famous African-American educator, Booker T. Washington, asked President Roosevelt to change his decision. But Roosevelt refused. Major Penrose, the commander, was put on trial for "neglect of duty." He was accused of trying to protect his soldiers. Penrose was found not guilty.

Congress Gets Involved

Many people across the United States, both black and white, were very angry about Roosevelt's actions. The black community, which had supported Roosevelt, started to turn against him. Roosevelt's administration kept the news of the soldiers' discharge quiet until after the 1906 elections. This was to avoid affecting the black vote.

The case became a big political issue. Leaders of major black organizations tried to stop the discharges, but they failed. From 1907 to 1908, the US Senate Military Affairs Committee investigated the Brownsville Affair. Most of them agreed with Roosevelt's decision.

However, Senator Joseph B. Foraker of Ohio pushed for the investigation. He wrote a report saying the soldiers were innocent. Another report from four Republicans said the evidence was too unclear to support the discharges. In September 1908, W. E. B. Du Bois urged black people to vote. He told them to remember how they were treated by the Republican government.

Feelings against the government remained strong. But when William Howard Taft became president and Foraker lost his re-election, some of the political pressure went down. Senator Foraker continued to work on the case. He helped pass a resolution to create a board to look into reinstating the soldiers. Roosevelt signed this bill on March 2, 1909.

On April 7, 1909, a Military Court of Inquiry was set up. It was meant to review the charges and recommend soldiers for re-enlistment. Out of 167 discharged men, 76 were found to be witnesses. Six did not want to appear. The court interviewed about half of the soldiers. It accepted 14 for re-enlistment, and eleven of them rejoined the Army. The government did not look at the case again until the early 1970s.

Later Investigation and Pardon

In 1970, a historian named John D. Weaver wrote a book called The Brownsville Raid. He argued that the soldiers were innocent. He also said they were discharged without a fair legal process, which is guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. After reading the book, Congressman Augustus Hawkins asked the Defense Department to re-investigate.

In 1972, the Army found the soldiers of the 25th Infantry to be innocent. Based on their recommendations, President Richard Nixon pardoned the men. He gave them honorable discharges, but without back pay. Most of these discharges were given after the soldiers had passed away. Only two soldiers were still alive from the affair. One had re-enlisted in 1910.

In 1973, Congressman Hawkins and Senator Hubert Humphrey helped pass a law. It gave a tax-free pension to the last survivor, Dorsie Willis. He received $25,000. He was honored in ceremonies in Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles.