Industrial Workers of the World facts for kids

|

|

| Founded | June 27, 1905 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Location |

|

|

Members

|

|

|

Key people

|

§ Notable members |

| Publication | Industrial Worker |

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a group of workers from different jobs who joined together to make things better for everyone. Its members are often called "Wobblies." This group started in Chicago in 1905. The name "Wobblies" has a fun, mysterious origin!

The IWW believes that all workers, no matter their job, should be part of "One Big Union." They think this unity can help workers have more say in their workplaces and improve their lives. They want to replace a system where a few people own everything with one where workers have more control. This idea is called "industrial democracy."

In the early 1900s, especially from 1910 to the early 1920s, the IWW grew very quickly. They helped workers in many different jobs, especially in the American West. At their strongest point in 1917, they had over 150,000 members in countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Many people joined the IWW for a short time, especially during strikes or tough economic times.

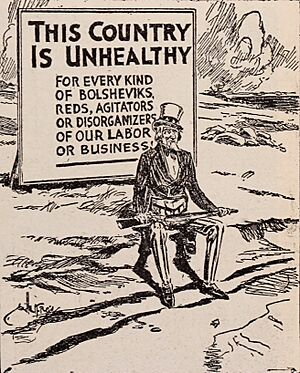

However, the IWW's membership started to shrink in the late 1910s and 1920s. They had disagreements with other worker groups, like the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The AFL thought the IWW was too extreme, while the IWW felt the AFL was too old-fashioned. Also, governments made it harder for groups like the IWW to operate, especially after World War I. In Canada, the IWW was even made illegal for a time in 1918.

A big reason for the IWW's decline was a major split within the organization in 1924. This made it hard for them to recover fully. In the 1950s, the IWW almost disappeared due to tough times for many groups that wanted big social changes. But in the 1960s and 1970s, new movements for social justice helped the IWW gain new energy and members.

The IWW still believes that all workers should unite as one group. They want to change the system where bosses control everything into one where workers have more power. They are known for their "Wobbly Shop" idea, where workers can choose their own managers and make decisions together. You don't have to work in a specific place to join the IWW, and you can even be a member of another union at the same time.

Contents

IWW in the United States

The IWW has a long history in the United States, where it first began.

Early Years: 1905–1950

How the IWW Started

The idea for the IWW began with a meeting in Chicago in 1904. Seven people attended, representing different worker groups. Important figures like Eugene V. Debs were also involved.

The IWW officially started in Chicago in June 1905. About 200 people who believed in big social changes and worker rights came together. They were from different parts of the United States. They all disagreed with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) because the AFL accepted the current economic system and didn't include all types of workers. The IWW wanted to unite all workers, skilled and unskilled, into one big group.

The first meeting was on June 27, 1905, and was called the "Industrial Congress." It later became known as the First Annual Convention of the IWW.

Many important people helped start the IWW. These included William D. ("Big Bill") Haywood, James Connolly, Lucy Parsons, and Mary Harris "Mother" Jones.

The IWW wanted workers to stick together to change the system. Their famous saying was "an injury to one is an injury to all." They thought this was better than an older saying, "an injury to one is the concern of all." The Wobblies believed that the AFL was not helping all workers and was dividing them by their specific jobs. The IWW wanted all workers to organize as one class. This idea is still part of their rules today.

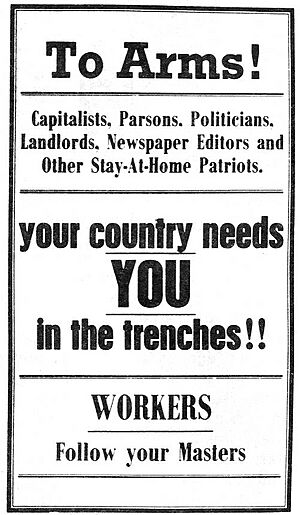

The IWW believed that workers and bosses have different goals. They felt that there could be no peace as long as many workers struggled while a few bosses had everything. They thought that workers needed to unite to take control of how things are made and end the system where people work for wages.

They also saw that big companies were becoming more powerful, making it hard for smaller worker groups to stand up for themselves. They believed that worker groups often fought against each other, which helped the bosses. The IWW wanted all workers in an industry to stop working if anyone in that industry went on strike. This would truly make "an injury to one an injury to all."

Instead of just asking for "a fair day's wage," the IWW wanted to end the wage system completely. They believed it was the workers' job to get rid of the current economic system. They wanted to organize workers not just for daily struggles but also to keep things running after the old system was gone. They saw themselves as building a new society within the old one.

The Wobblies were different from other worker groups because they wanted all workers in an industry to join one union, not just those with specific skills. They focused on ordinary workers making decisions, rather than powerful leaders. Early IWW groups often refused to sign long-term contracts. They believed these contracts limited workers' ability to help each other during tough times. The Wobblies imagined that a "general strike" (where many workers stop working at once) could change the whole system. They wanted a system that cared more about people than money, and more about working together than competing.

One of the IWW's most important contributions was that it was the only American union at the time to welcome all workers. This included women, immigrants, African Americans, and Asians. Many early members were immigrants, and some, like Joe Hill, became important leaders. People from Finland made up a large part of the immigrant IWW members. Their Finnish-language newspaper, Industrialisti, was the union's only daily paper and was very popular. The IWW also had schools and meeting places for its Finnish members.

The union was committed to treating everyone equally. For example, Local 8 in Philadelphia, a group of dock workers, had over 5,000 members. Most were African American, but it also included many immigrants and white workers. This showed how the IWW brought different groups together.

Different Ideas: Action or Politics

In 1908, some IWW members, led by Daniel De Leon, thought that working through politics was the best way to reach the IWW's goals. But another group, led by Bill Haywood, believed that direct actions like strikes, spreading ideas, and boycotts were more effective. Haywood's group won the debate, and De Leon's supporters left to form their own version of the IWW.

How the IWW Organized

The IWW first became well-known in Goldfield, Nevada, in 1906. They also gained attention during a strike at a steel car factory in Pennsylvania in 1909. Later that year, they became famous for fighting for "free speech." In Spokane, Washington, the town made street meetings illegal. When an IWW organizer was arrested for speaking, many other Wobblies came to the spot and asked to be arrested too. This made it too expensive for the town to keep arresting everyone. In Spokane, over 500 people went to jail, and four people died. This tactic of fighting for free speech helped the IWW gain support and keep their right to organize openly.

By 1912, the IWW had about 25,000 members. They were strong among dock workers, farm workers, and in textile and mining areas. The IWW was involved in over 150 strikes, including big textile strikes in Lawrence (1912) and Paterson (1913).

Where the IWW Was Active

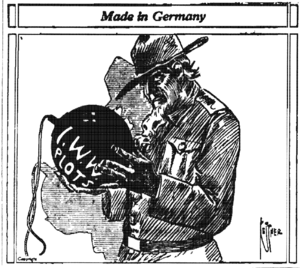

In its early years, the IWW started over 900 worker groups in more than 350 cities and towns across the U.S. and Canada. They had 90 newspapers and magazines in 19 different languages. Cartoons were a big part of IWW publications, making fun of their opponents and spreading their messages. The IWW was active all over the country, including in the Seattle General Strike of 1919. They also helped Mexican workers in the Southwest and became a strong union for dock workers in Philadelphia.

IWW vs. Other Unions

In 1906 and 1907, the IWW became very powerful in Goldfield, Nevada, a gold-mining town. They could even set wages and working conditions. However, the AFL-affiliated Carpenters Union resisted the IWW. This led to mine owners refusing to hire IWW members. The owners closed their mines, hoping to break the IWW's power. This caused a split among workers.

The mine owners asked for federal troops to help. With the troops' protection, the mines reopened with non-union workers, which weakened the IWW's influence in Goldfield.

Leaders of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), like Bill Haywood, helped create the IWW. The WFM joined the IWW at first. However, many WFM members didn't like the IWW's radical ideas and wanted to stay independent. This caused disagreements.

When WFM leaders were accused of a crime, the IWW helped pay for their legal defense. Even though they were found not guilty, it hurt the IWW because the public still thought they were guilty. This also caused a big disagreement between Haywood and another WFM leader. The trials made the WFM want to move away from violence and radicalism. In 1907, the WFM left the IWW.

Historians say that the IWW sometimes tried to destroy local unions they couldn't control. From 1908 to 1921, the IWW tried to gain power in WFM local groups. When they couldn't, they tried to weaken the WFM, which caused that union to lose many members.

The IWW wanted the WFM to rejoin them because the WFM had many strong miners who were good allies. In 1908, a leader named Vincent St. John tried to secretly take over the WFM. He wanted IWW supporters to become delegates at the WFM convention and vote for pro-IWW leaders. But his plan did not work.

The IWW also had conflicts with the United Mine Workers union in 1916. The IWW tried to stop UMWA members from working because the IWW thought the UMWA was too traditional. The UMWA called the police to protect its members who wanted to work. The police arrived and prevented violence, allowing UMWA members to cross the IWW picket lines.

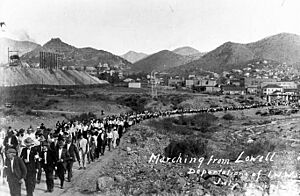

Bisbee Deportation

In 1916, the IWW decided to organize workers in the copper mines of Arizona. Copper was very important during World War I. In 1917, thousands of miners joined the IWW. The main focus was Bisbee, Arizona, where nearly 5,000 miners worked. On June 27, 1917, the Bisbee miners went on strike. The strike was peaceful, and they demanded higher pay and safer working conditions.

However, on July 12, hundreds of armed citizens rounded up almost 2,000 striking workers. They forced 1,186 of them into cattle cars and left them in the New Mexico desert. In the days that followed, hundreds more were told to leave. The strike was ended by force.

Other Organizing Efforts

Between 1915 and 1917, the IWW's Agricultural Workers Organization helped over 100,000 traveling farm workers in the Midwest and West. Many IWW members at this time were "hobos" who traveled by train to find work. Train cars were often covered with IWW messages.

Building on this success, the IWW also organized lumberjacks and other timber workers from 1917 to 1924. An IWW lumber strike in 1917 led to workers getting an eight-hour day and much better working conditions.

From 1913 to the mid-1930s, the IWW's Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union was a strong force, organizing dock workers. They believed in international unity among workers. Local 8 in Philadelphia, led by Ben Fletcher, an African American, organized mostly African American dock workers, along with immigrants and other white workers. The IWW also had a presence in many other ports around the world.

Wobblies also helped with "sit-down strikes" and other organizing efforts by the United Auto Workers in the 1930s, especially in Detroit.

Even when the IWW won strikes, like in Lawrence, it was sometimes hard to keep their gains. The IWW in 1912 didn't like formal agreements with bosses. They believed in constant struggle. It was hard to keep that strong revolutionary spirit going. In Lawrence, the IWW lost most of its members after the strike as bosses made it difficult for union supporters. In 1938, the IWW changed its rules to allow contracts with employers, as long as they didn't stop strikes.

Government Actions Against the IWW

The IWW faced very strong opposition from governments, companies, and even groups of citizens. In 1914, Wobbly Joe Hill was accused of murder in Utah and was executed in 1915, even though many thought the evidence was weak. In 1916, in Everett, Washington, a group of armed citizens attacked Wobblies on a ship, killing at least five union members.

Many IWW members were against the United States joining World War I. They believed that wars were mainly for rich people to get richer, and that poor workers ended up fighting and dying for them. An IWW newspaper wrote: "Capitalists of America, we will fight against you, not for you!"

When the U.S. declared war in April 1917, the IWW tried to keep a low profile to avoid problems. They stopped printing anti-war messages. After much discussion, they issued a statement against the war but told members to follow draft laws. They advised members to register for the draft and write "IWW, opposed to war" on their forms.

Even with this, the IWW's anti-war stance made them very unpopular. Frank Little, a strong IWW war opponent, was killed in Montana in August 1917.

During World War I, the U.S. government took strong action against the IWW. In September 1917, government agents raided IWW offices across the country, taking many documents. Based on these documents, 166 IWW leaders were accused of trying to stop the draft and cause problems in labor disputes. In 1918, 101 of them went on trial and were all found guilty, receiving long prison sentences. Bill Haywood, a key IWW leader, fled to the Soviet Union to avoid prison.

In 1917, in an event called the Tulsa Outrage, a group of people attacked 17 IWW members in Oklahoma. They were covered in tar and feathers. This was said to be revenge for not supporting the war. Local police had arrested the IWW members and given them to this group.

In 1919, a parade in Centralia, Washington, turned into a fight between parade members and IWW members. Four parade members were shot. It's not clear who started the violence, but there had been earlier attacks on the IWW hall. Several Wobblies were arrested, and one, Wesley Everest, was killed by a mob that night. A plaque honoring the IWW members involved was put up in Centralia in 2023.

IWW members faced legal action under various laws. In 1920, many foreign-born IWW members were targeted.

Split and Later Years

The IWW recovered quickly after 1919 and 1920, with membership reaching a high point in 1923. But ongoing arguments within the group, especially about whether to have a strong central leadership or let local groups decide more, led to a major split in 1924.

In the 1920s, many IWW leaders and members left to join Communist groups.

In 1949, the IWW was put on a government list of "subversive organizations," meaning groups trying to change the government in illegal ways. This made it hard for IWW members to get federal jobs or housing.

The IWW's largest group at the time, the Metal and Machinery Workers Industrial Union (MMWIU), left the IWW in 1950. This was a huge blow. The MMWIU itself later disappeared.

The loss of the MMWIU almost destroyed the IWW. Membership dropped to its lowest point in the 1950s. By 1955, the union's 50th anniversary, it was almost gone.

New Life: 1950–2000

The 1960s brought new energy to the IWW. The civil rights movement, protests against war, and student movements helped the IWW gain new members, though not as many as in its early days.

The IWW started organizing students in San Francisco and Berkeley. By 1964, a local group there had over 100 members. Old and new Wobblies joined together for another "free speech fight" in Berkeley. In 1967, the IWW decided to let college students join as full members. This led to new campaigns at universities. The IWW also gained members from student groups that were having internal problems. By 1972, most IWW members were under 30 years old.

The IWW's connection to the 1960s counterculture led to organizing efforts at businesses that fit that style. Many co-ops (businesses owned by their workers) joined the IWW under their "Wobbly Shop" model. These were mostly printing, publishing, and food distribution businesses. This connection sometimes caused legal trouble, like when a printing shop in Montreal was shut down for publishing banned materials.

Back to Workplace Campaigns

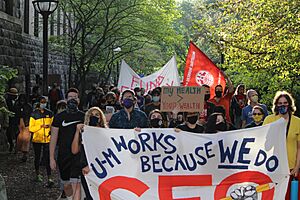

With new members, the IWW started many organizing campaigns. These were mostly in specific regions like Portland, Chicago, Ann Arbor, and California.

In Portland, Oregon, the IWW organized workers at a brass plating plant, a donut shop, and a daycare. They also organized healthcare and farm workers. This led to opening an IWW union hall in Portland.

In California, the IWW was active in Santa Cruz. In 1977, they tried to organize 3,000 workers hired under a government program. This led to pay raises and better benefits, but the union couldn't keep its strong presence there. However, they did win lasting victories at other places in Santa Cruz.

In Chicago, the IWW opposed "urban renewal" programs and supported creating a "People's Park." The Chicago group also organized healthcare, food service, entertainment, construction, and metal workers. They even tried to organize fast food workers at a McDonald's in 1973.

In Ann Arbor, the IWW organized workers at a college bookstore. They won official recognition in 1979 after a strike, and the store became a strong union shop until it closed in 1986.

In the late 1970s, the IWW became known for organizing in the entertainment industry. They formed an Entertainment Workers Organizing Committee in Chicago. IWW musicians like Utah Phillips toured and promoted the union.

Other IWW campaigns in the 1970s included supermarkets, food companies, chemical workers, fast food workers, hospital workers, shipyard workers, and construction workers.

1990s Activities

In the 1990s, the IWW was involved in many worker struggles and free speech fights.

In 1996, the IWW started organizing at Borders Books in Philadelphia. They lost a vote to become the official union, but they kept organizing. When an IWW member was fired, they started a national boycott of Borders. IWW members protested at Borders stores across the country.

Also in 1996, the IWW began organizing at Wherehouse Music in California. The campaign continued until 1997, when management fired organizers and cut hours for union members. This affected the union vote, which the IWW lost.

In 1998, the IWW started a group for Marine Transport Workers in San Francisco. They trained many dock workers in safety techniques.

In 1999, the IWW started a group for Education Workers in Boston, organizing workers at local colleges.

Other IWW organizing drives in the late 1990s included a strike at a mini-mart in Seattle, and work with homeless and youth centers. IWW members were also active in construction, shipyards, hotels, restaurants, and railroads.

The IWW also helped workers in other unions, like sawmill workers in California and concession stand workers in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Recent Years: 2000–Present

In the early 2000s, the IWW organized a fabric shop in Berkeley, California, which is still an IWW shop today. The city of Berkeley's recycling is also handled by IWW-organized businesses.

In 2003, the IWW started organizing street people and others in non-traditional jobs, forming the Ottawa Panhandlers' Union. A year later, this union led a strike by homeless people. They negotiated with the city, which agreed to fund a newspaper written and sold by homeless people.

Between 2003 and 2006, the IWW organized unions at food co-ops in Seattle and Pittsburgh.

In 2004, an IWW union was formed at a Starbucks in New York City. In 2006, the IWW continued organizing at Starbucks shops in Chicago.

In Chicago, the IWW also started organizing bicycle messengers.

In September 2004, IWW-organized truck drivers in Stockton, California, went on strike and won almost all their demands.

In New York City, the IWW has organized immigrant food workers since 2005. Workers at several warehouses joined the IWW and gained things like minimum wage and overtime pay.

In 2006, the IWW moved its main office to Cincinnati, Ohio, but moved back to Chicago, Illinois, in 2010.

In May 2007, New York City warehouse workers and Starbucks workers formed a combined union. In the summer of 2007, the IWW organized workers at two more food warehouses. Workers at these places were illegally fired for their union activities. In 2008, these workers fought to get their jobs back and receive owed overtime pay. They won settlements against their employers.

The IWW has also tried new ways of organizing, like focusing on retail workers in a specific business area in Philadelphia.

The union has also spoken out on other issues, like protesting the war in Iraq and supporting a boycott of Coca-Cola for issues related to workers' rights in Colombia.

In July 2008, the IWW Starbucks Workers Union in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and a union in Seville, Spain, organized a global day of action against Starbucks. They protested the firing of two union members.

The Portland, Oregon, IWW branch is one of the largest and most active. It currently has contracts with two organizations. There is some discussion within the branch about whether these contracts are the best way to organize. The branch has successfully helped workers who were wrongly fired, getting them compensation. Membership in Portland has been growing. As of 2005, the IWW had about 5,000 members worldwide. Other IWW branches are in Australia, Austria, Canada, Ireland, Germany, Uganda, and the United Kingdom.

2011 Wisconsin Protests

In early 2011, Wisconsin's governor announced a budget bill that the IWW believed would make it very hard for public worker unions to exist. In response, IWW groups in the Midwest met. The IWW suggested a general strike, and this idea was supported by other worker groups. The Madison branch of the IWW asked unions in other countries for support. This was seen as one of the IWW's biggest actions since the 1930s. However, the strike efforts were later overshadowed by efforts to recall the governor.

Late 2010s Activities

In the mid-2010s, the IWW in the U.S. focused on organizing workers at Starbucks, Jimmy John's (a sandwich chain), and Whole Foods Market. The union had about 3,000 members. The IWW moved its headquarters to Chicago in 2012.

The IWW organized a campaign at Chicago-Lake Liquors in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 2013. The store had a low wage limit. When the IWW demanded higher wages, the store fired five organizers. The union protested, and the government later found that the store had unfairly fired the workers. The union and store agreed to a $32,000 payment to the fired workers.

In 2015, workers at the Paulo Freire Social Justice Charter School in Massachusetts organized with the IWW. They wanted to address problems with the school's leadership and hiring practices.

In September 2015, workers at Sound Stage Production in Connecticut announced they were IWW members. They were soon threatened with legal action and fired. After negotiations, the workers received back pay and severance.

The IWW announced the Burgerville Workers Union (BVWU) in April 2016. This union focuses on workers at the Burgerville fast food chain in Oregon. The BVWU gained support from local groups and even Senator Bernie Sanders. In June 2017, Burgerville paid $10,000 because they had violated state rules about worker breaks. In 2018, the IWW won elections at two Burgerville locations.

In August 2016, workers at Ellen's Stardust Diner in Manhattan formed a union under the IWW. This happened after 30 employees were fired and a new, unpopular scheduling system was put in place. The union accused management of firing people in revenge for union activity.

On September 9, 2016, the IWW's Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee helped organize a national prison strike. This strike, supported by other groups, focused on poor conditions in prisons and very low pay for prisoners. It affected many prisons in different states and was called the "largest prisoner strike in recent memory."

COVID-19 Pandemic Efforts

The IWW also organized workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. In May 2020, the IWW started the Voodoo Doughnut Workers Union (DWU) in Portland, Oregon. The union demanded higher wages, better safety, and severance pay for laid-off workers. In February 2021, DWU workers officially asked for a union election.

In May 2020, the IWW also announced the Second Staff (2S) workers' union at the Faison school, a private school for students with autism in Richmond, Virginia. The union formed because they felt the school was putting staff and students at risk by trying to open too soon.

March 2021 saw more IWW organizing. Workers at Moe's Books, an independent bookstore in Berkeley, California, announced they were unionizing with the IWW, and the management agreed.

Soon after, on March 13, the IWW announced it was organizing workers at the Socialist Rifle Association (SRA), and the SRA recognized the union the next day. On March 16, staff at the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition announced they wanted to unionize with the IWW. They wanted fair pay, clear rules, and the right to have union representation in meetings about their jobs.

The IWW is the first union in the United States to get a union contract for fast food workers. Five Burgerville locations and one Voodoo Doughnut location in Oregon are now unionized.

IWW in Australia

The IWW's ideas reached Australia early on. This was partly because a local socialist group followed the IWW's industrial approach. The IWW started a club in Sydney in 1907.

The early Australian IWW used tactics from the U.S., like fighting for free speech. They often worked with existing unions instead of forming their own. Unlike the U.S. IWW, they were very open about opposing World War I. The IWW's strategies greatly influenced the Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union. This union created "closed shops" (where only union members could work) and worker councils, which helped control how bosses treated workers in the late 1910s.

The IWW strongly opposed World War I from 1914 and fought against Australia forcing people to join the army. Australians voted against this idea twice, making Australia the only country fighting in World War I that didn't force people to join the army. This was largely due to the IWW's efforts, even though they never had more than 500 members in Australia. The IWW started the Anti-Conscription League and spread strong messages against the war. This led to the imprisonment of Tom Barker, the editor of the IWW paper Direct Action, in 1916.

A series of fires at businesses in Sydney were thought to be part of the IWW's campaign to free Tom Barker. He was released, but 12 IWW activists were arrested in September 1916 for arson and other crimes. Their trial and imprisonment became a famous case for the Australian worker movement, as many believed there wasn't enough evidence against them. The IWW was also blamed for other scandals and for the defeat of the conscription vote. In December 1916, the Australian government declared the IWW an illegal organization. Eighty-six members immediately broke the law and were jailed. The IWW's newspaper was shut down. During the war, over 100 IWW members in Australia were jailed for political reasons.

The IWW continued to operate illegally, trying to free its jailed members. They briefly joined with other radical groups to form a communist party, but the IWW left it soon after.

By the early 1930s, most Australian IWW groups had disappeared as the Communist Party became more influential.

The Australian IWW has grown since the 1940s but has not been successful in getting official union recognition. Many former IWW members joined mainstream worker movements. For example, Donald Grant, one of the "Sydney Twelve" who was jailed, later became a politician for the Australian Labor Party. This shows that many ex-IWW members stayed involved in the broader worker movement.

"Bump Me Into Parliament" is a well-known Australian IWW song, still sung today.

IWW in New Zealand

Australia had a strong influence on worker groups in New Zealand in the early 1900s. Some founders of the New Zealand Labour Party were from Australia.

"Wobbly" activists in New Zealand before World War I included John Benjamin King and H. M. Fitzgerald from Canada, and Robert Rivers La Monte from America. IWW groups were strong in Auckland, Wellington, mining towns, on the docks, and among laborers.

IWW in Canada

The IWW was active in Canada very early in its history, especially in Western Canada. The union organized many workers in the lumber and mining industries. Joe Hill wrote the song "Where the Fraser River Flows" during this time. Some IWW members had close ties with the Socialist Party of Canada.

Arthur "Slim" Evans, a famous organizer, was once a Wobbly. He was also a friend of Ginger Goodwin, a Canadian who was shot during World War I for resisting the war. Ginger Goodwin's story influenced many progressive groups in Canada.

Even though the IWW was banned in Canada during World War I, it quickly recovered after the war. In 1923, it reached a high of 5,600 Canadian members. The union had a "golden age" in Canada, with its main office in Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay, Ontario). It had a strong base among immigrant workers, especially Finns, who worked as farm workers, lumberjacks, and miners. The IWW's Finnish newspaper competed with other publications. Membership slowly decreased in the 1920s and 30s as the IWW faced competition from other worker groups. However, the IWW and these groups sometimes worked together during strikes.

In 1936, the IWW in Canada supported the Spanish Revolution and helped recruit volunteers to fight in Spain. This led to conflicts with other groups recruiting for different sides. Several Canadian IWW members died in the Spanish Civil War. By World War II, IWW membership had dropped, but it grew again by 1946. After this, the IWW declined in Canada, becoming more of a social club for Finnish members. In 1973, the Canadian main office was closed, and Canadian groups were managed by the U.S. office. IWW activity in Canada shifted to supporting strikes and worker activism.

By the late 1990s, the IWW in Canada started to grow again. In 2009, Canadian members voted to create a Canadian Regional Organizing Committee (CanROC) to help groups work together better.

In 2009, the IWW helped form the Starbucks Workers' Union in Quebec. Leaders faced problems after unionizing, and their efforts were eventually defeated.

Today, the IWW is active in many Canadian cities. CanROC helps coordinate these groups. There are currently five "job shops" (places where the IWW has a strong presence) in Canada. The Ottawa Panhandlers' Union continues the IWW's tradition of including all types of workers, even those who make a living on the street. In 2004, this union led a strike by homeless people, which resulted in the city funding a newspaper created and sold by the homeless.

Recently, the IWW has also organized harm reduction workers and workers at a Quebec fast food chain.

IWW in Europe

Germany, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Austria

The IWW started organizing in Germany after World War I. A German Language Membership Regional Organizing Committee (GLAMROC) was founded in December 2006 in Cologne. It covers German-speaking areas and has groups or contacts in 16 cities. In 2023, GLAMROC had about 500 members.

United Kingdom and Ireland

The IWW's group in the United Kingdom and Ireland is called the Wales, Ireland, Scotland, England Regional Administration (WISERA).

Early History

Groups supporting the IWW were founded in Britain in 1906. The first IWW group in Britain was started in 1913.

The IWW was involved in many worker struggles in the early 1900s, including the UK general strike of 1926. During the Spanish Civil War, an IWW member from Wales helped train volunteers to fight in Spain.

After World War II, the IWW had two active groups in London and Glasgow, but they later disappeared. There was a small comeback in northwest England in the 1970s.

Membership

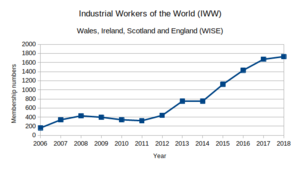

Between 2001 and 2003, membership in the UK increased. By 2005, there were about 100 members in the United Kingdom. For the IWW's 100th anniversary, a stone was placed in Wales to remember the union. The IWW officially became a recognized union in the UK in 2006.

The IWW now has groups in many major cities and regions. Membership has grown quickly, reaching over 1,500 members in 2016.

Campaigns

IWW members were involved in the Liverpool dock workers' strike from 1995 to 1998, and many other struggles. They also successfully unionized several workplaces.

Recently, the IWW has focused on health and education workers. In 2007, they launched a campaign against cuts in the National Blood Service.

Also in 2007, IWW groups in Glasgow and Dumfries helped successfully stop the closure of a university campus. This success, along with the Blood Service campaign, has made the IWW more well-known.

In 2011, the IWW helped cleaners win back pay and the right to negotiate with their employers. Also in 2011, new IWW groups were set up in Lincoln, Manchester, and Sheffield, including for workers at Pizza Hut.

In 2014, the Edinburgh IWW group joined other groups in supporting social action. In 2015, they joined a network against government spending cuts.

In 2016, WISERA promoted a campaign for couriers working for companies like Deliveroo.

Iceland and Greece

An Iceland Regional Organizing Committee (IceROC) was started in 2015.

Also in 2015, a Greek Regional Organizing Committee (GreROC) was formed. In July of that year, it spoke out against the Greek government's response to a public vote, saying that a big change was needed.

IWW in Africa

South Africa

The IWW has a rich history in South Africa. An IWW group was founded there in 1910 and existed until about 1916. The union believed in uniting all races, which was against the white worker movement and led to harsh government actions. The port of Durban was an important link in the IWW's international network, connecting North America to ports in Africa, India, and other places.

After the IWW group in South Africa ended, it was followed by other worker groups, including the Industrial and Commercial Workers' Union (ICU), which became the main Black worker union in the 1920s and 30s.

Almost 100 years later, there were attempts to restart the South African IWW, but they were not successful.

Sierra Leone and Uganda

In 1997, 3,240 workers in Sierra Leone, mostly miners, registered as IWW members. This happened mostly on their own, without much contact with the main IWW office. Contact was lost after a military takeover in Sierra Leone. Some members had to flee to Guinea.

In 2012, IWW members in Uganda formed a Ugandan Regional Organizing Committee. However, this group was later dissolved because its leaders broke IWW rules, like allowing bosses to join.

Songs and Music

One special thing about the Wobblies from the beginning has been their love for songs. To counter bosses who would send bands to drown out IWW speakers, Joe Hill wrote funny versions of Christian songs. This way, union members could sing along but with their own messages. For example, "In the Sweet By and By" became "There'll Be Pie in the Sky When You Die (That's a Lie)".

From this start, writing Wobbly songs became common because they "showed the frustrations, anger, and humor of the homeless and the struggling." The IWW collected its official songs in the Little Red Songbook, which is still updated today. In the 1960s, a folk music revival in the U.S. brought new interest in Joe Hill's songs. Famous folk singers like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie were supportive of the Wobblies, and some were even members.

Some well-known protest songs in the book include "Hallelujah, I'm a Bum" and "Union Maid". Perhaps the most famous IWW song is "Solidarity Forever". Many artists have performed these songs. Utah Phillips performed them for decades. Other important IWW songwriters include Ralph Chaplin, who wrote "Solidarity Forever."

The Finnish IWW community also produced many folk singers and songwriters. The most famous was Matti Valentine Huhta, known as T-Bone Slim, who wrote "The Popular Wobbly" and "The Mysteries of a Hobo's Life." Hiski Salomaa, who sang in Finnish, is a recognized folk musician in Finland and in areas of North America with many Finns. He has been called the Finnish Woody Guthrie. Arthur Kylander was another important Finnish IWW folk musician. His songs were about the challenges of immigrant workers and also had humorous themes. The idea of a "wanderer" was common in Finnish folklore and fit well with the music of these IWW songwriters.

Books About the IWW

A large part of the story in the U.S. novels by American writer John Dos Passos is about the IWW. Several of the characters the author liked most are IWW members. These books show the author's support for the IWW and his anger about how it was treated.

Karl Marlantes's 2019 novel Deep River looks at worker issues in the early 1900s in the U.S. and how they affected a Finnish immigrant family. The book focuses on a woman in the family who becomes an IWW organizer in the dangerous logging industry. It explores different views on worker rights, especially IWW strikes and the backlash against the worker movement during World War I.

Wobbly Words

Wobbly lingo is a collection of special words and phrases used by the Wobblies for over a hundred years. Many Wobbly terms came from or are similar to words used by "hobos" (traveling workers) in the early 1900s. The exact origin of the name "Wobbly" is not known. For many years, many hobos in the U.S. were IWW members or supported them. Because of this, some terms describe the life of a hobo, like "riding the rails" (traveling on trains) or "jungles" (hobo camps). The IWW's efforts to organize workers in all jobs meant their language grew to include terms related to mining, timber work, and farming.

Some words and phrases that started with Wobbly lingo are now used more widely. For example, from Joe Hill's song "The Preacher and the Slave", the phrase "pie in the sky" is now commonly used to mean a "goal that is too good to be true."

Famous Members

Some very famous people have been members of the IWW, or were rumored to be. These include:

- Noam Chomsky (a well-known thinker and writer)

- Tom Morello (a musician)

- Jeff Monson (a mixed martial arts fighter)

- Andy Irvine (a musician)

- David Graeber (a late anthropologist)

It has long been rumored that baseball legend Honus Wagner was also a Wobbly, but this has not been proven.

|

See also

In Spanish: Industrial Workers of the World para niños

In Spanish: Industrial Workers of the World para niños

- Eugene V. Debs

- Industrial democracy

- Industrial Revolution

- Industrial Workers of the World philosophy and tactics

- One Big Union (concept)

- Seattle General Strike

- Solidarity unionism

- Syndicalism

- Women in labor unions

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |