Western Federation of Miners facts for kids

| Merged into | United Steelworkers, Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) |

|---|---|

| Founded | May 15, 1893 |

| Dissolved | 1967 (1993 in Sudbury, Ontario) |

| Location |

|

|

Key people

|

Charles Moyer (President), "Big Bill" Haywood |

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a labor union for miners in the western United States and British Columbia, Canada. A labor union is a group of workers who team up to ask for better pay and safer working conditions. The WFM became famous for being very bold and determined.

The union often got into serious conflicts with mining companies and the government. These conflicts were sometimes like battles. One of the biggest struggles was the Colorado Labor Wars from 1903 to 1904. The WFM also helped start a larger group of unions called the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1905.

In 1916, the WFM changed its name to the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers, often called Mine Mill. After some quiet years, the union grew strong again in the 1930s. However, in the 1950s, during a time of great fear about Communism in America, the union was kicked out of a major labor organization for having Communist leaders. After many more years of struggle, Mine Mill joined with the United Steelworkers union in 1967.

Contents

How the WFM Began

Miners in the late 1800s had a very tough job. They worked deep underground in dangerous conditions for low pay. Before the WFM was created, small groups of miners tried to form unions, but they often failed.

A big event that led to the WFM was a strike in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, in 1892. During the strike, a fight broke out and five strikers died. The governor called in the U.S. army, which arrested 600 strikers and held them in a makeshift prison called a stockade. The miners in Coeur d'Alene received a lot of help from a miners' union in Butte, Montana.

This experience showed miners that small, local unions were not strong enough to stand up to the powerful mine owners. So, on May 15, 1893, about 40 miners' representatives met in Butte. They decided to join their unions together to form one large, powerful union: the Western Federation of Miners.

Major Events in WFM History

A Victory in Cripple Creek (1894)

The WFM's first big test came in Cripple Creek, Colorado. Mine owners tried to make the workday longer, from eight hours to ten, without extra pay. The miners went on strike to protest.

This was a rare case where the state government actually helped the workers. The governor sent the state militia to protect the striking miners from armed men hired by the companies. In the end, the mine owners agreed to go back to an eight-hour day and pay the miners three dollars a day. This victory helped the WFM grow much larger over the next ten years.

The Leadville Strike (1896–97)

A strike in Leadville, Colorado, did not go as well. The union asked for a small pay raise for the lowest-paid workers. The mine owners refused and locked all the union workers out of the mines.

The situation turned violent, and several people were killed in a fight at the Coronado Mine. The governor sent in the Colorado National Guard, and the strike eventually failed. This defeat made the leaders of the WFM believe they needed to take even stronger actions to win their fights.

Conflict in Coeur d'Alene (1899)

Another major conflict happened in Coeur d'Alene. After the Bunker Hill Mining Company fired 17 union members, angry miners used dynamite to destroy one of the company's buildings.

In response, Idaho's Governor Frank Steunenberg asked President William McKinley to send the army. Soldiers rounded up about 1,000 men, whether they were involved or not, and put them in a fenced-in camp called a "bullpen." Many were held for months without being charged with a crime.

The Colorado Labor Wars (1903–04)

By 1903, the WFM was one of the most determined unions in the country. They tried to organize workers at smelters, which are factories that melt down ore to get the metal out. These workers were paid even less than miners.

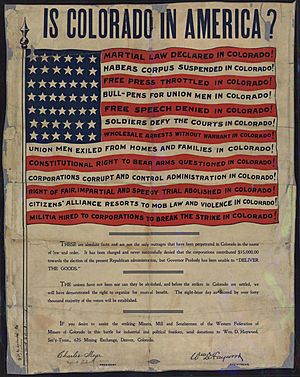

When smelter workers in Colorado City went on strike, Colorado's Governor James Hamilton Peabody took the side of the companies. He sent in the National Guard, which was paid for by the businesses, not the state. The commander, General Sherman Bell, arrested hundreds of strikers and union leaders.

The conflict grew more intense. After a bomb exploded at a train station, killing 13 non-union workers, anti-union groups attacked WFM members and destroyed their union halls. General Bell and the National Guard forced hundreds of striking miners to leave the area. These events, known as the Colorado Labor Wars, were a major defeat for the WFM in Colorado.

Founding the IWW

After the defeats in Colorado, the WFM decided it needed more allies. In 1905, its leaders, including the famous "Big Bill" Haywood, helped create a new, nationwide organization called the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

The IWW's goal was to unite all workers into "One Big Union" to challenge the power of big companies. However, disagreements soon broke out within the IWW. By 1907, the WFM left the new organization it had helped create.

A Famous Trial

In 1905, the former governor of Idaho, Frank Steunenberg, was killed by a bomb. Authorities arrested three WFM leaders: President Charles Moyer, Secretary Bill Haywood, and member George Pettibone. They were accused of planning the crime.

The case became famous across the country. The union hired Clarence Darrow, one of the best lawyers in America, to defend the men. The trial was a huge event, with powerful mining companies helping to pay for the prosecution. Despite the pressure, Darrow won the case. Haywood and Pettibone were found not guilty, and the charges against Moyer were dropped.

Later Years as "Mine Mill"

The WFM faced hard times after 1910. A major strike in Michigan in 1913-1914 ended in defeat. During that strike, a terrible tragedy occurred when someone falsely shouted "fire" at a Christmas party for strikers' families. In the panic, 73 people, including 62 children, were crushed to death. This is known as the Italian Hall Disaster.

In 1916, the union changed its name to the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (Mine Mill). The union became strong again in the 1930s and 1940s.

However, during the "Red Scare" of the 1950s, a time of intense fear of Communism, Mine Mill was expelled from the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a large federation of unions. This was because some of Mine Mill's leaders were communists. For the next 17 years, the union struggled. Finally, in 1967, Mine Mill merged with the United Steelworkers, a larger and more powerful union.

Salt of the Earth: A Movie About the Union

In 1954, a movie called Salt of the Earth was made about a real strike by Mexican-American zinc miners in New Mexico who were members of Mine Mill.

The film was very controversial. It was directed by a filmmaker who had been blacklisted in Hollywood for his political beliefs. Many of the actors were real miners and their families, not professionals. The movie's star was even deported to Mexico during filming. Because of the controversy, very few theaters in the U.S. would show the film. Today, it is seen as an important piece of American film history.

See also

- Anti-union violence

- Vincent Saint John

- Industrial Workers of the World

- Jencks v. United States

- Progressive Miners of America

- The Ladies Auxiliary of the International Union of Mine Mill and Smelter Workers

- Seeberville Murders