Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cripple Creek miners' strike |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

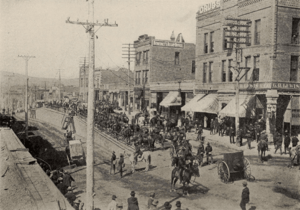

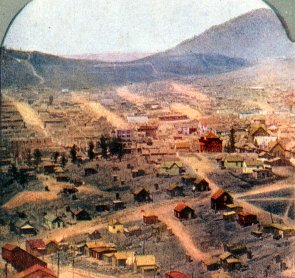

View of Cripple Creek, c. 1900

|

|||

| Date | February 7 – June 12, 1894 | ||

| Location | |||

| Goals | Wages | ||

| Methods | Strikes, protest, demonstrations | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Losses | |||

|

|||

The Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894 was a five-month long strike by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) in Cripple Creek, Colorado, United States. It was a big win for the union. This strike is special because it was the only time in U.S. history that a state's army (called a militia) was sent to help striking workers.

The strike involved intense conflicts and the use of dynamite. It ended after a tense standoff between the Colorado state militia and a private group hired by the mine owners. After this strike, the WFM union became much more popular and powerful in the region.

Contents

Why the Strike Happened

In the late 1800s, Cripple Creek was the biggest town in a gold-mining area. This area included other towns like Altman and Victor. Gold was found here in 1891. Within three years, more than 150 mines were digging for gold.

A financial crisis in 1893 caused the price of silver to drop. But the price of gold stayed the same. Many silver miners came to the gold mines, which led to lower wages for everyone. Mine owners then wanted miners to work longer hours for less money.

In January 1894, some big mine owners, including J. J. Hagerman, David Moffat, and Eben Smith, made a change. They employed one-third of the miners in the area. They announced that the workday would become ten hours instead of eight. But the daily pay would stay at $3.00. When workers complained, the owners offered eight hours of work for only $2.50 a day.

Around this time, miners in Cripple Creek had formed their own union. When the new changes started, they joined the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Their local group was called Local 19. The union had offices in Altman, Anaconda, Cripple Creek, and Victor.

On February 1, 1894, the mine owners began the 10-hour workday. A week later, union president John Calderwood demanded the owners go back to the eight-hour day with $3.00 pay. When the owners did not reply, the new union started a strike on February 7. Some smaller mines quickly agreed to the eight-hour day and stayed open. But the larger mines refused.

What Happened During the Strike

The strike quickly had a big impact. By the end of February, all gold processing plants in Colorado were either closed or working part-time. In early March, two more mines, Gold King and Granite, agreed to the eight-hour day.

Mine owners who still wanted the 10-hour day tried to reopen their mines. On March 14, they got a court order telling miners not to stop their operations. They also hired strikebreakers, who were workers brought in to replace the striking miners. The WFM first tried to convince these new workers to join the union. When that didn't work, the union used threats and some forceful actions. These methods successfully made the non-union miners leave the area.

On March 16, a group of armed miners stopped and captured six sheriff's deputies. A conflict started, and one deputy was shot. An Altman judge, who was a WFM member, charged the deputies with carrying hidden weapons. He then released them.

State Militia Gets Involved

After his deputies were attacked, Sheriff M. F. Bowers asked the governor for help. He wanted the state militia to step in. Governor Davis H. Waite, a 67-year-old Populist, sent 300 troops to the area on March 18. The general in charge, Adjutant General T. J. Tarsney, found the area tense but calm. Union president Calderwood promised that union members would cooperate. He even said they would surrender if asked. Tarsney believed that Sheriff Bowers had made the situation sound worse than it was. So, he suggested taking the troops away, and Governor Waite agreed. The state militia left Cripple Creek on March 20.

After the state militia left, the mine owners closed their mines. Sheriff Bowers arrested Calderwood, 18 other miners, and the mayor of Altman. They were taken to Colorado Springs and quickly tried. But they were found not guilty. Meanwhile, conflicts like stone-throwing and fights between union miners and strikebreakers happened more often. Stores were broken into, and guns were stolen.

In early May, the mine owners met with WFM representatives in Colorado Springs. They tried to end the strike. The owners offered to go back to the eight-hour day. But they would only pay $2.75 a day. The union said no, and the talks failed.

Sheriff Forms His Own Army

Soon after talks with the union ended, the mine owners secretly met with Sheriff Bowers. They told him they planned to bring in hundreds of non-union workers. They asked if he could protect such a large group. Bowers said he couldn't, because the county didn't have enough money to pay many deputies. The mine owners offered to pay for about a hundred men to start. Bowers agreed and began hiring former police and firefighters from Denver.

News of this meeting quickly spread. The miners organized and armed themselves in response. Calderwood left to raise money for the strike. He put Junius J. Johnson, a former U.S. Army officer, in charge of the strike. Johnson immediately set up a camp on Bull Hill, which overlooked the town of Altman. He ordered his men to build defenses, gather supplies, and practice drills.

Dynamite at the Strong Mine

On May 24, the strikers took control of the Strong mine on Battle Mountain. This mine overlooked the town of Victor. The next day, around 9 AM, 125 deputies arrived in Altman. They set up camp at the bottom of Bull Hill. As they started to march toward the strikers' camp, miners at the Strong mine blew up the building over the mine shaft. The explosion sent parts of the building flying over 300 feet into the air. Moments later, the steam boiler was also dynamited. This showered the deputies with wood, iron, and cables. The deputies quickly ran to the train station and left town.

A celebration broke out among the miners. Some miners loaded a flatcar with dynamite and tried to roll it towards the deputies' camp. It overturned before reaching its target. Other miners wanted to blow up every mine, but Johnson quickly stopped them. Some miners then took a work train and went into Victor. They caught up with the fleeing deputies, and a gun battle started. One deputy and one miner died. Six strikers were captured by the deputies. The miners later captured three officials from the Strong mine. Everyone was eventually exchanged, freeing all prisoners.

Calderwood returned that night and brought calm back to the area. He asked saloons to close and held several miners who had caused trouble.

On May 26, mine owners met again with Sheriff Bowers. The owners agreed to give more money so the sheriff could hire 1,200 more deputies. Bowers quickly recruited men from all over the state. He set up a camp for them in the town of Divide, about 12 miles from Cripple Creek.

Governor Waite Steps In Again

Governor Davis Hanson Waite was warned about the large force Sheriff Bowers was gathering. He stepped in again on May 27. He issued a statement telling the miners to leave their camp on Bull Hill. In a very unusual move for American labor history, he also declared the 1,200 deputies to be an illegal group. He ordered them to break up. He also told the state militia to be ready to move on Cripple Creek. On May 28, the governor visited the miners. They gave him permission to negotiate for them.

An early meeting on May 30 almost ended badly. Waite, Calderwood, and mine owners Hagerman and Moffat met at Colorado College. Talks were going well when a crowd of local citizens tried to storm the building. They blamed Calderwood and Waite for the violence and wanted to harm them. A local judge distracted the crowd, and Calderwood and Waite escaped out a back door to the governor's waiting train.

Negotiations continued in Denver on June 2. An agreement was reached on June 4. The agreement said that the miners would get their $3.00-per-day wage and the eight-hour day back. The mine owners agreed not to punish any miner who had been part of the strike. The miners agreed not to treat non-union workers badly.

State Militia Returns

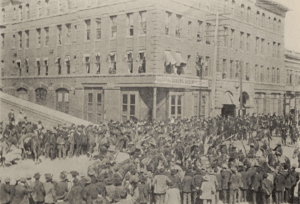

Sheriff Bowers had 1,300 deputies in Cripple Creek, but he couldn't control them. On June 5, the deputies moved into Altman. They cut the telegraph and telephone lines and held several reporters. Governor Waite was worried the private army might get out of control. So, he sent the state militia again, this time led by General E.J. Brooks.

When Colorado state troops arrived on June 6, more violence had already started. The deputies were shooting at the miners on Bull Hill. General Brooks quickly moved his troops to the base of Bull Hill. As Sheriff Bowers and General Brooks argued, the deputies tried to charge the miners. The miners blew a whistle at the Victor mine, alerting General Brooks. State militia soldiers quickly stopped the deputies. Brooks ordered his men to take over Bull Hill, and the miners did not fight back.

The deputies then focused on Cripple Creek town itself. They arrested many citizens without reason. Many people were grabbed from the street or their homes. They were hit and kicked. The deputies made people walk through a line of them, spitting and hitting them. With Bull Hill secured, General Brooks began to arrest the deputies. By nightfall, Brooks had control of the town and had rounded up all of Bowers' men.

Governor Waite threatened to declare martial law, which means the military would take over. But the mine owners refused to disband their deputy force. General Brooks then threatened to keep his troops in the area for another 30 days. The owners realized they would have to pay for an army that couldn't do anything. So, they agreed to disband it. The deputies were sent by train to Colorado Springs and began to leave on June 11. The agreement started the same day, and the miners went back to work.

Union president Calderwood and 300 other miners were arrested. Only four miners were found guilty of any charges. They were quickly pardoned by the sympathetic governor.

What Happened After the Strike

The Cripple Creek strike was a huge win for the miners' union. The Western Federation of Miners used this success to organize almost every worker in the Cripple Creek area. This included waitresses, laundry workers, bartenders, and newsboys. They formed 54 local unions. The WFM was very strong in Cripple Creek for almost ten years. They even helped elect most county officials, including the new sheriff.

The Cripple Creek strike also greatly changed the Western Federation of Miners as a political group. The union was only a year old and very weak before the strike. But after, it became highly respected by miners across the West. Thousands of workers joined the union in the next few years. Politicians and labor leaders across the country became allies of the union. The WFM became a powerful political force throughout the Rocky Mountain West.

However, the WFM's success at Cripple Creek also caused a negative reaction. Employers saw the WFM as a dangerous and violent group. The WFM never again had as much public support in a local strike as it did in Cripple Creek in 1894. When the union struck the Cripple Creek mines again in 1898, public support ended after violence broke out. During another strike in 1903–4, called the Colorado Labor Wars, the union faced both the employers and the state government.

The union's success also changed Colorado politics. People in Colorado blamed Governor Waite for protecting the miners' union and encouraging violence. This led to Waite losing the election in November 1894. Republican Albert McIntire was elected instead. The Populist movement in Colorado never recovered.

The Cripple Creek strike of 1894 also made mine owners more determined. Under Governor McIntire, the Colorado government worked closely with the mine owners. Mine owners increasingly used detective agencies for spies. They also increased the use of strikebreakers. They started using lockouts (temporarily closing workplaces) and blacklists (lists of workers not to hire) to control union members.

After a rifle and dynamite attack by striking miners on two mines during the Leadville Miners' Strike in 1896, the WFM lost that strike. This caused the WFM to break away from the American Federation of Labor. They then became more politically radical. After the Colorado Labor Wars, the WFM helped start the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1905. Although the IWW was important for a short time, its ideas still influence the American labor movement today.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Huelga de Cripple Creek para niños

In Spanish: Huelga de Cripple Creek para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |